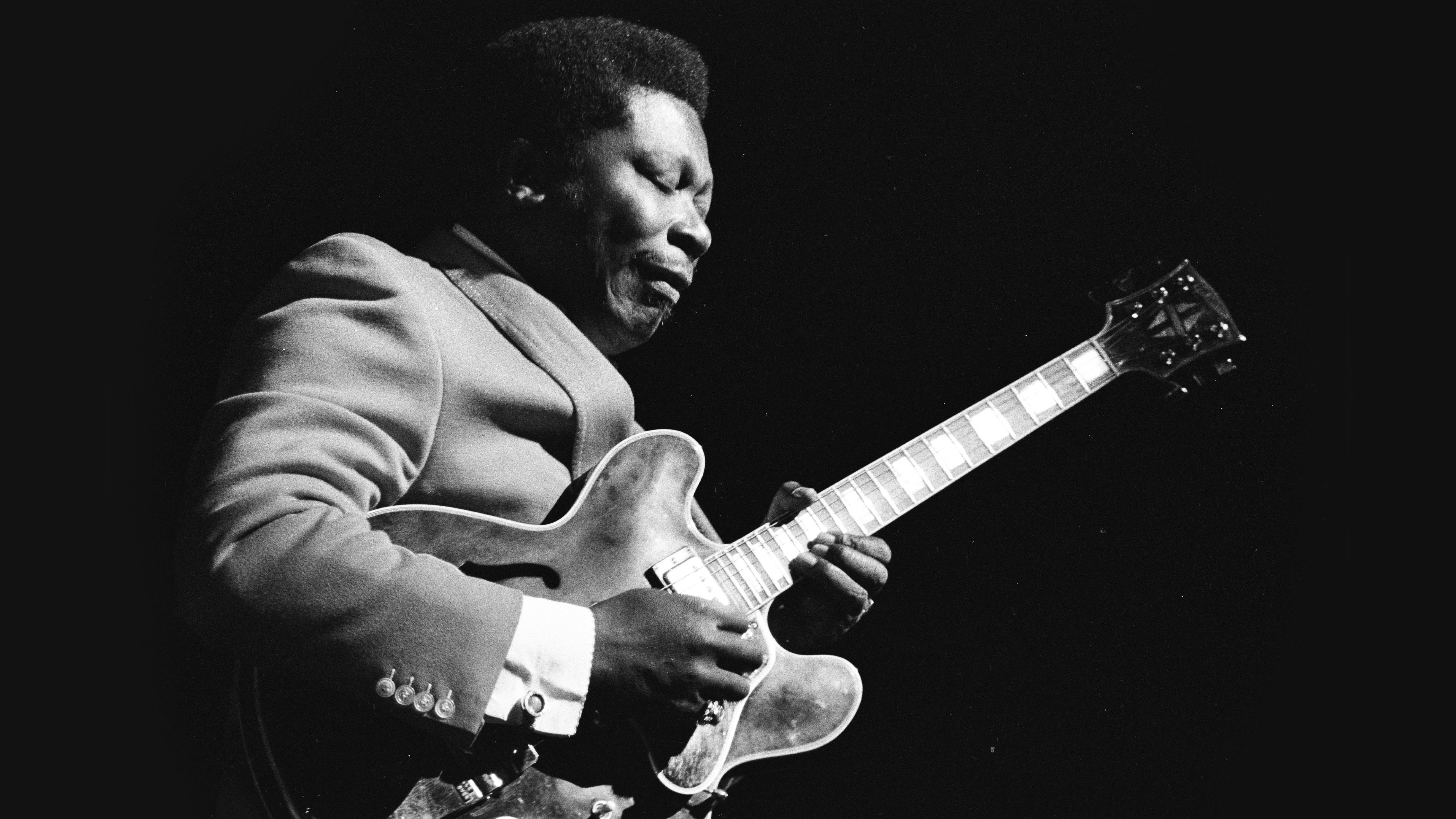

5 songs guitarists need to hear by… BB King

The King Of The Blues was a pioneer, icon and a statesman of the music he played. But the fine details of his playing hold valuable lessons for guitarists of any genre

It’s five years since the King Of The Blues died, aged 89, and the outpouring of tributes from the music world ensured he was sent off in fitting style. Famously, he was perhaps the only guitarist who could be recognised from one note, an achievement that was the result of his totally idiosyncratic approach to the instrument. But how did his unique style arise?

He left obsessing about gear and even effects to others: a semi-hollow ES-345-style guitar, a heavy pick, a lead and an off-the-shelf combo amp were his tools. So rather than obsessing over diodes and neck profiles, King listened closely to then translated and refined the ideas of the musicians he loved into a lyrical guitar style based on the overriding priority of communication.

On the guitar front, some of his inspirations were Lonnie Johnson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charlie Christian, T-Bone Walker, Django Reinhardt and Bukka White, his cousin. But listen to him talk in interviews about his guitar style and he not only references other instrumentalists, particularly sax players, but vocalists, too. BB King thought of his guitar playing, with its bends, its spaces, its calls and responses and its emotional dynamics, as one half of a conversation. It’s the biggest lesson he left for other guitarists, and one that’s rarely taken to heart by the legions of players who he influenced.

Listening closely to his solos is, and always will be, a lesson for guitarists. Here, we’ve chosen just five tracks that show how BB King could endlessly vary his approach to suit the context of the song or the venue he was playing.

1 Three O’Clock Blues (Singin’ The Blues, 1957)

BB King’s first chart hit back in 1951 seems as good a place as any to start, for a listen to the raw materials that launched his seven-decade career – and also since none of his previous seven singles had charted and without this breakthrough record, his route to stardom may have been much harder as a result.

A ghostly blues lament, Three O’Clock Blues is refreshingly undominated by the blare of the era’s ever-present horns; instead, they reflect the insomniac subject matter by wheezing away in the distance while Ike Turner tinkles away unobtrusively on piano, leaving BB space to display the interplay of his guitar and voice to its fullest.

You can hear the influence of both T-Bone Walker and the song’s author, Lowell Fulson in King’s use of space and single-tone bends and insistent hammer-ons and slurs, respectively, plus – in the final turnaround – a hint of the jazz style that inflected BB’s early playing. BB’s Lucille at this point was an ES-125 hollowbody with a single P-90, and its full-bodied, slightly overloaded tone adds to the haunting quality of the song, which was recorded with a portable studio setup at the black YMCA in Memphis.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Singin’ The Blues, the 1957 album that collects together his early singles, reveals him to be a creative and varied guitarist, although he hadn’t yet fully developed his trademark – his uniquely rapid wrist-heavy single-finger vibrato – or expanded his vocabulary of expressive bends to anything like the heights he would reach later.

2. Chains And Things (Indianola Mississippi Seeds, 1970)

BB King could magically mould the same phrases and notes to convey completely different emotions – how he did it is a mystery, and one of the many things that elevates him above blues guitarists who focus on flashy technique over meaningful content. On Chains And Things, you can hear it in the space of a song: the diffident, mournful opening notes of his intro and vocal Q&As transforms throughout the song into a more strident and aggressive voice, until, by the song’s end, Lucille sounds every bit as frustrated as BB himself is by the injustices he references in the song’s lyrics.

The song is from Indianola Mississippi Seeds, the 1970 album he considered “the best album I have ever made artistically”. It was produced by Bill Szymcyzk, who had masterminded King’s commercial breakthrough hit The Thrill Is Gone the same year and went on to produce the likes of Hotel California and more), and he encouraged King to embrace a more creative approach in the studio and move away from the winning but now waning formula of pure blues that had become his stock in trade.

Chains And Things has a moment that captures this newfound creative openness in full flight. The song’s second solo section begins with what BB described as a ‘mistake’: “I played the wrong note and followed it as best I could... then we got the arranger to make the strings follow it,” he said. Listen to the resulting section and what they ended up with was a menacing refrain that matches the song’s moody minor-key atmosphere to perfection. The moral of the tale? As Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies cards say, sometimes it pays to “Honor thy error as a hidden intention…”

3. Gambler’s Blues (Blues Is King, 1967)

Recorded at the International Club in Chicago in 1966, this live record showcased BB in a stripped-down band setting, with financial circumstances (a bus crash and an IRS claim) having temporarily forced him to trade the big-band entourage of the kind heard on Live At The Regal for organ, alto sax and trumpet.

Gambler’s Blues is a fine example of how King used contrasts, space and repetition to stoke the energy of his audience

But no matter – if anything, the small-club setting makes him work even harder, feeding off the interaction with the hyped-up crowd to ramp up his showmanship, take an extra dose of gravel for his extraordinary blues holler and pull out all the stops with his guitar playing. There’s lots of variety in his playing throughout the set: stinging, biting licks adorn uptempo crowdpleaser Blind Love, a gritty major-minor workout steals midtempo shuffle Tired Of Your Love, and reverb-drenched, dark-toned edge-of-feedback licks haunt the slow-blues of Night Life.

Yet for pure visceral fretboard thrills, Gambler’s Blues is a fine example of how King used contrasts, space and repetition to stoke the energy of his audience. Its first minute and a half is a pure outpouring of six-string expression, full of telling detail: he varies his dynamics through all of the tools at his disposal (altering his pickup selector, tone and volume controls, even turning his reverb off at one point), and sets the stage for the song’s vocal by dotting his phrasing with frantic string rakes, piercing high bends, varying the register and tempering the minor-key angst with touches of major-key sweetness.

4. The Thrill Is Gone (Completely Well, 1969)

BB King’s first million-selling single reached No. 15 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1970, no mean feat for a blues single in any era, but extra-special at the turn of the new decade. The Thrill Is Gone broke new ground for the genre, and for BB King himself, thanks to the addition of its mournful string arrangement by Bert de Coteaux. The song was originally written by Roy Hawkins and Rick Darnell in 1951, but King’s version thoroughly reworks the original, retaining its minor key but jettisoning everything else.

The idea to fuse King’s well-honed melancholy with this expansive overdubbed violin instrumentation, ornamented by Wurlitzer electric-piano lines, belonged to producer Bill Szymczyk, who also recruited session players Herbie Lovell on drums, bassist Gerry Jemmott, keys player Paul Harris and guitarist Hugh McCracken instead of King’s erstwhile road band, to record in New York’s Hit Factory studio in September 1969.

The basic track took just three takes, with no overdubs required

For the song’s guitar parts, King set up in the studio with the core band, using a Gibson ES-355 with Varitone engaged through a Fender Twin Reverb. He recorded the song live with no guitar or vocal overdubs, peeling off tense, worried notes from Lucille throughout before stretching out on the single-chord outro jam, weaving in and out of the other instruments with calm authority.

The basic track took just three takes, with no overdubs required. When the strings were added in a separate session, the potential of the sound became apparent to King. Producer Szymczyk recalled to mixonline.com: “When you look at the big picture, this was the track that took him off the ‘chitlin’ circuit and put him in Vegas. I think he could hear that about to happen as we recorded the strings. No wonder he was smiling so big.”

5. Worry Worry Worry (Live In Cook County Jail, 1971)

Guitar lesson: 5 of BB King's game-changing guitar solo tricks

BB performed, on average, an astonishing 200-plus shows a year into his 70s, and among these were around 70 performances in prisons. He was an advocate for improving prison conditions and in 1972, co-founded FAIRR, the Foundation for the Advancement of Inmate Recreation and Rehabilitation. Following the success of Johnny Cash’s late-60s prison albums, King accepted an invitation to perform at Chicago’s Cook County Jail in 1971.

It was one of America’s most notorious penitentiaries and King’s band played on a small stage in front of over 2,000 mostly male, mostly African-American prisoners, for whom extra security had been arranged. King and his six-piece band was recorded using a hired mobile studio and press surrounding the event was a factor that helped lead to eventual reform of the prison.

The usual tough crowd and captive audience clichés most certainly applied, then, but it’s testament to King’s character that far from shrinking into himself and racing through the hits, he approached the situation with an almost evangelical zeal. In the words of his biographer, Sebastian Danchin: “The prisoners saw King’s visit as an all-too-rare recognition of their humanity,” and King responded by using everything at his disposal to create a connection.

This is best summed up by the 10-minute rendition of slow blues Worry, Worry, Worry at the heart of the set, where the band delivers false endings, builds and fades behind King’s vocal, which switches from raw gospel-preacher hollering and sax-like falsetto to spoken-word Q&A. But before preaching, BB turns to his guitar and does what he does best – communicate through it – delivering multiple verses of vocal licks that seem to answer their own questions before entering into subtle dialogue with the horn section.