5 songs guitarists need to hear by… Eric Clapton (that aren't Layla)

Five killer guitar performances that show why Slowhand has been a household name for seven decades and counting

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There is a fair bit to choose from when it comes to picking just five of Eric Clapton’s guitar tracks that other guitarists should hear. As an example, the selections here don’t even include anything from his solo career – which, as of 2020, spans 50 years, 23 studio albums, 18 Grammy Awards and over 100 million album sales.

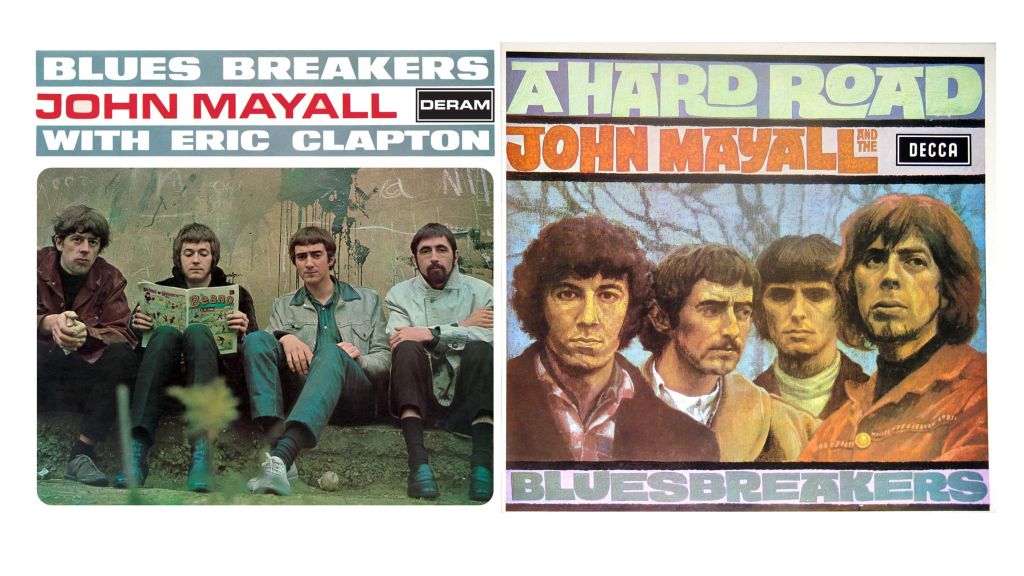

But it’s testament to just how ahead of the curve he was in the latter half of the 60s that you don’t need to venture beyond that era to be convinced of his six-string genius: and for that, most Clapton fans would argue that you could really just listen to one album – 1966’s seminal John Mayall’s Blues Breakers Featuring Eric Clapton.

Yet the further away we get from the electric guitar’s golden era, the easier it is to take for granted the scale of his innovations and influence on the players that came after him. On the gear front, we refer to his pairing of the Les Paul with a Marshall combo, but he’s also done much to enhance the reputation of the ES-335, the SG, the Firebird, the Martin acoustic, the wah pedal, Fender amps… then, of course, there’s the Strat. His mongrel ‘Blackie’ model, when auctioned in 2004, became the most expensive guitar in the world and is certainly one of the most iconic instruments in all of music.

What we have chosen, then, are five songs that show how Clapton evolved his sound over the space of five formative years, between 1966 and 1970. Each one is a lesson in terms of technique and expressiveness in its own right, of course, but hopefully, they also show a guitarist whose restless musicality drove him way beyond channelling his influences to develop his own distinctive sound. At the end of the day, that’s surely the goal of all guitar players… and Clapton has done it better and for longer than pretty much anyone else.

1. Steppin’ Out – John Mayall Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton, 1966

The album that unleashed the hitherto underrated talents of the ex-Yardbirds guitarist to the world in 1966 completely redefined electric guitar tone. It was the birthplace of the LP-through-Marshall sound (a 1960 was it 1959? Les Paul Standard through a Marshall Model 1962 2x12 combo), with Clapton skilfully manipulating his pickup selector, playing dynamics and volume and tone controls to maximise the impact of the sound.

The story of of the greatest guitar handover in blues history

Yet as groundbreaking as this tone was, the ‘Beano’ album proves the adage that it really is ultimately all in the fingers. Steppin’ Out – the heavily reworked version of Memphis Slim’s piano-blues song from 1959, with a solo by Matt ‘Guitar’ Murphy – provided the perfect instrumental backdrop to showcase how hard Clapton had worked to squeeze every drop of musicality out of his powerful setup’s extra sustain, feedback and warmth.

Steppin’ Out’s rapid fingerslides, vicious vibrato and use of space in its phrasing took blues guitar to a new level of sophistication. It was clear evidence that the 21-year-old had managed to channel and incorporate the styles he obsessively mimicked on blues records into something entirely fresh. And the version on 1968’s Live Cream Volume II offers a fascinating contrast to his original, varying the swing and taking the song into looser improvisational territory.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

2. Sunshine Of Your Love – Cream, Disraeli Gears, 1967

The young EC had made his name with a blistering and sophisticated take on the guitar styles of his blues heroes, but as he stretched out with Cream, his own style evolved beyond his influences. Though still a blues aficionado at heart (parts of the solo on Strange Brew are a note-for-note tribute to Albert King, for example), Cream’s merging of pop, blues, rock and psychedelia, forged during night after night of improvisation in a power-trio setting, saw him quickly elevate his playing into an artform.

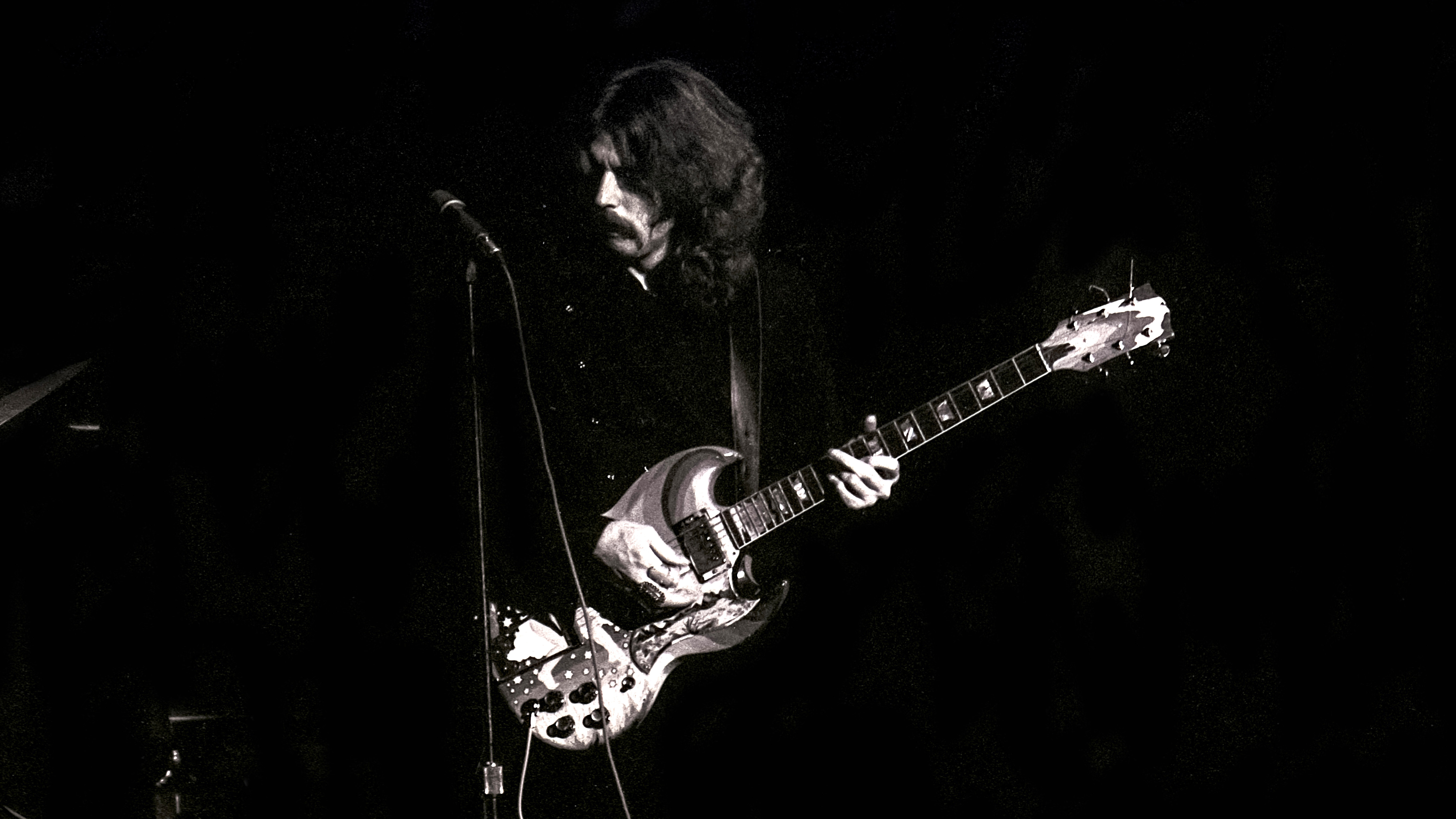

Sunshine Of Your Love, from the band’s 1967 album Disraeli Gears, would have been Cream’s signature song even if it had no solo at all, thanks to its all-time-classic riff. But add to this the definitive example of Clapton’s fabled ‘woman tone’ (achieved by rolling off the tone control on his 1964 ‘The Fool’ SG), the reference to the melody of Blue Moon in the solo’s opening notes, and Clapton’s decision to contrast the song’s aggressive riff with laid-back major-pentatonic focused leadwork, and you have an example of Clapton at the peak of his powers as a lead guitarist.

3. Crossroads – Cream, Wheels Of Fire, 1968

Cream’s 1968 San Francisco live performance of Crossroads, on half-live, half-studio double album Wheels Of Fire, is a high-water mark not just for EC, but for electric blues playing in general. Maybe the feeling that the fractious trio was on the edge of disintegration – both on the night and as a band – that brought the best out of him, because this “kerfuffle” as he called it is a chaotic gift that keeps on giving.

Almost certainly using his 'Fool’ SG through Marshalls, he orchestrates a psychedelic take on the blues that builds relentlessly from its restrained hybrid-picked intro to the dizzy heights of its wild outro, mixing major and minor modes and showing off his full repertoire of bends, doublestops, triplet licks and fluid phrasing along the way. It shows Clapton’s effortless ability to improvise endlessly creative, musical solos with intensity and finesse.

Yet the man himself has never understood the idolatry for the performance, telling Guitar World: “I’ve always had that held up as like, ‘this is one of the great landmarks of guitar playing’. But most of that solo is on the wrong beat. Instead of playing on the two and the four, I’m playing on the one and the three and thinking, ‘that’s the off beat’. No wonder people think it’s so good – because it’s fucking wrong.”

4. Badge – Cream, Goodbye, 1969

It appeared on an album called Goodbye, so it’s fair to say that by 1969, Cream were pretty committed to going their separate ways. And Badge, a Clapton co-write with George Harrison – who’s credited as ‘L’Angelo Misterioso’ and contributes rhythm guitar to the track – reveals that by this point, EC was itching to explore different styles of music, despite having left the Yardbirds only a few years earlier, seemingly unable to forgive their poppy infidelities.

An outlier in the Cream catalogue, Badge is a melancholy, chorus-less pop oddity that’s an ensemble performance: the band’s only song to feature five people. But musically, with the addition of piano and Mellotron, it sounds like a different band altogether.

The middle section finds Clapton playing a timeless D-chord based arpeggio figure through a Leslie cabinet set to a slow revolution to match the one happening in his own musical development at the time. When it comes to the song’s solo, EC turns the Sunshine of Your Love trick on its head, drowning the song’s mournful changes with aggressive minor-pentatonic flurries, delivering a composition-within-a-composition solo that hints at the more expansive direction Clapton was about to travel in…

5. Have You Ever Loved A Woman – Derek And The Dominos, Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs, 1970

That’s not to say that, from the 70s onwards, EC turned his back on the blues. No matter how much he experimented over the subsequent decades (and he strayed as far as to pick up a Roland guitar synth on 1985’s Behind The Sun, for example – don’t listen to it, just know that it happened), the genre was always somewhere in his orbit. This 1970 cover of a Billy Myles/Freddie King calling card shows how his recent adoption of a Strat as his instrument of choice had changed his playing.

Have You Ever Loved A Woman – which he’d played live with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers five years earlier – is an example of how chameleonic Clapton could be. A slow-burning, brooding blues delivered by a killer band.

Featuring Duane Allman on second guitar contributing an expressive, sympathetic slide break as a warm-up act, the song comes to life when Clapton steals the spotlight around the four-minute mark, constructing fluid solos with breathtaking bends, channelling all the fire and passion of his earlier incarnations into a more loose-limbed, fearless style reminiscent of the emotionally charged attack of Buddy Guy. Tone-wise, he used his iconic ‘Brownie’ Stratocaster into a dialled tweed Fender Deluxe, altering his approach on-the-fly to take full advantage of every ounce of Californian dirt this new setup offered him.