Sonic destruction: the science of distortion and how to use it

From hard clipping to reduced bitrates, there's plenty of creativity to be found by doing things just a little bit wrong

Right back since the earliest days of recorded music, musicians and producers have been making use of techniques that are technically ‘wrong’ for creative purposes. Just look at the adventurous techniques used by The Beatles in Abbey Road, or the leftfield sound creation of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

In the 21st century, there are multiple techniques and production approaches used regularly by electronic music makers which originated as things that were technically ‘wrong’ – errors, malfunctions or misused gear that turned out to create musically pleasing results.

The most obvious example is distortion, which is essentially the byproduct of trying to push a piece of recording gear harder than intended. There are multiple other ‘wrong’ techniques worth adding to your arsenal of production skills though; from glitch-like digital pseudo-malfunctions to purposefully raw and lo-fi recording techniques.

What is distortion?

Distortion, in a music production context, is derived from the non-linear behaviour of classic recording gear – the way analogue circuits respond differently depending on the amplitude of the audio signal passed through them.

While recording gear is generally designed to be as close to linear as possible within the normal range of operation, push any analogue circuit harder than intended and it will begin to alter the shape of the waveform.

The most extreme example of this is what’s known as hard clipping, where a device with a hard limit on the amplitude of a waveform – such as an analogue to digital converter – effectively lops off the top of the waveform, turning a sine wave into a square.

Hard clipping can sound harsh and abrasive, but most analogue devices – and plugins that emulate them – have a softer and more subtle response. This results in a more gradual harmonic distortion that increases as you raise the level of the input signal, resulting in pleasing new harmonics and a slow rolling off of high frequencies.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It’s this effect, used with a light touch, that’s responsible for much of what we know as ‘analogue warmth’.

In the early days of recording technology, distortion was often seen as an unwanted side effect of misused gear or recordings made at the wrong level. As the decades have gone on though, it’s increasingly been viewed as an important creative effect.

In the digital realm, for one thing, the floating point maths used by modern DAWs – resulting in vast amounts of potential headroom – means that tracks can end up feeling cold and ‘digital’ due to an absolute lack of natural distortion.

Creatively, distortion can do very interesting things to sounds that can change depending on the type of source material used. A distortion effect won’t sound identical on all sources; due to the way distortion creates new harmonic content, the results can vary depending not only on the level of the audio used, but the pitch and complexity.

Guitarists have long made use of this. A three note chord – comprised of the root, perfect fifth and octave above the root note – doesn’t sound like much played ‘clean’ but a healthy dose of distortion and the result is the familiar, rich ‘power chord’ sound.

This is the result of intermodulation, which is what happens when we distort two or more waveforms at once. In the case of straightforward harmonic distortion – applying distortion to a single waveform – new harmonic series partials are added above the frequency of the original waveform.

When you distort multiple waveforms together, new partials are then added at the sum and difference frequencies of the two original waves. This means that the results can sound grittier and less musical – depending on the frequency of the original waves – and that the process can result in new frequency content added below the original waves.

This can be desirable, such as adding heft to a simple guitar chord, but can also cause mix problems further down the line; when applying distortion across a group of sounds or complex chord, it’s often worth applying a filter after the effect to roll off unwanted frequencies.

Classic analogue approaches to distortion can impart other qualities to the sound too. For example, tube (or valve) devices tend to alter the dynamics of a sound as well as the frequency content; they exhibit a subtle ‘memory’ behaviour, whereby the circuit responds based on what’s just happened previously. The result is a subtle compression and taming of transients.

Valve distortion devices – common to classic guitar amps, among other things – also create asymmetrical distortion. Asymmetry, when talking about distortion, means that the positive side of a waveform isn’t affected in the same manner as the negative.

Some waveshapes, such as square or triangle waves, are symmetrical. These symmetrical waves feature only odd harmonics, and produce a sound that’s often described as ‘hollow’.

Processing a symmetrical wave through an asymmetrical distortion will create asymmetrical results, introducing even harmonics as found in saw or pulse waves. The audible effect is a ‘sweeter’ and richer distorted sound, compared to symmetrical distortion.

Many modern plugins offer controls to adjust these characteristics, making virtual distortion sound more or less symmetrical. Another common control found on distortion effects is some form of ‘colour’ control, which usually amounts to an integrated EQ to adjust the frequency response of the effect, boosting or attenuating high or low frequencies.

Analogue-style distortion isn't the only game in town

Distortion comes in numerous guises. With stompboxes and analogue gear, you often hear of effects referred to as saturation, overdrive or fuzz, which are variations of the same thing.

Saturation is subtle distortion, pushed lightly to create a pleasing, almost ‘hi-fi’ effect. Overdrive is the sound of a valve circuit pushed at its upper limits, while fuzz is a transistor-based effect, creating a distortion tone more focused on the higher frequencies.

In modern production gear, however, it’s common to find several forms of distortion effect that deviate from the classic analogue-style processes. Let’s look at some…

Bitcrushing

This is a purely digital form of sound degradation. It involves decreasing the accuracy of a digital audio file by decreasing bit depth (and/or sampling rate). This gives a simplified digital sound, which can sound crunchy, lo-fi and distorted in a distinctly digital way.

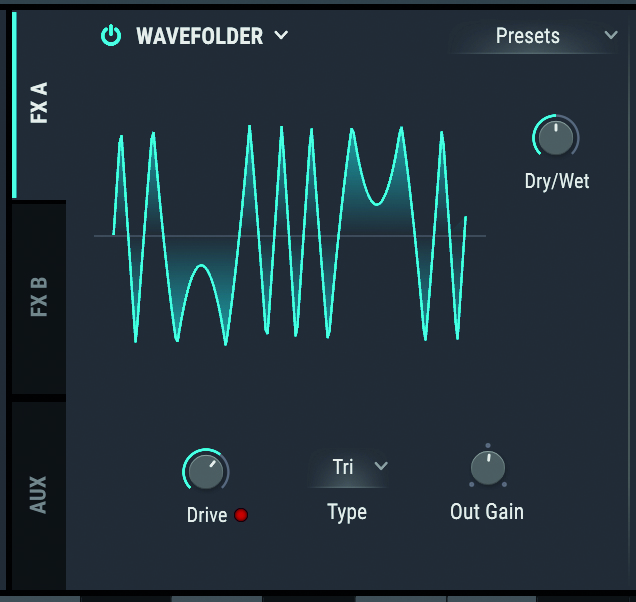

Wavefolding

Wavefolding works by inverting the ‘peaks’ of a waveform. Like hard clipping, this has the result of flattening a waveform over a certain threshold, although here the peaks are folded back in on themselves to create a new, more complex waveshape.

Frequency modulation

Generally a form of synthesis, but, depending on the frequencies and waves involved, it can make distortion-like tones too. The most obvious form comes when using a noise oscillator as a source to modulate the pitch of another oscillator or the cutoff frequency of a filter.

Three distortion power tips

1. Cut the chord

Distorting full chords can create unpleasant tones due to intermodulation. Try distorting each note of a chord separately – duplicate your part so that each note has its own track and apply separate distortion effects to each. The results will sound very different – and potentially more musical – than distorting the whole.

2. Break the chain

Distortion can be heavily altered by placing other effects before or after it in a chain. A distortion after reverb can sound great, for example, for creating squashed, gritty reverb tails for shoegaze-style effects.

A modulated filter before a distortion can have an interesting impact on how the effect responds, particularly with resonance. A compressor before a distortion plugin gives a more consistent tone; after, it helps to shape the resulting signal.

3. Modulate your parameters

Try automating or modulating distortion parameters in order to keep the sound fresh throughout a track. Evolving the tonal colour, symmetry or level of the effect can also be a great way to add movement.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.