Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Four good-looking, mop-topped young men racing through a tight set of smash tunes for a stadium full of shrieking girls. It's an image we almost exclusively associate with The Beatles, but it's a phenomenon that another quartet came to experience during a two-year period in the mid-'60s.

While it is true that The Monkees (Micky Dolenz, drums and vocals; Mike Nesmith, guitar and vocals; Davy Jones, vocals; and Peter Tork, guitar and vocals) were constructed by TV producers to capitalize on the massive popularity of The Beatles (think the snappy style of A Hard Day's Night right in your living room every week), what's surprising is how well it all worked: In 1967, The Monkees, propelled by hits such as Last Train To Clarksville, I'm A Believer, Pleasant Valley Sunday and Daydream Believer, surpassed both The Beatles and The Rolling Stones on the charts.

Hit records begat touring, which meant that the group had to cut it live. Most of the heavy lifting fell on Dolenz's shoulders - although he had experience as a guitarist and singer prior to being cast in the show, his drumming was limited to, as he puts it, "sitting behind a kit every once in a while and bashing around." But the former child actor, displaying De Niro-ian-like skill and determination, not only learned to play the drums in a year but became a solid, inventive ace, playing and singing lead vocals(!) with zeal and grace to walls of blinding flashbulbs and crushing screams.

Monkeemania has a way of popping up every other decade or so, and this November, brought about in part as a tribute to Jones, who passed away last February, Dolenz, Tork and Nesmith will mount a 12-city US tour. It comes during a busy time for Dolenz, who has just released a wildly entertaining new album called Remember, which sees the singer covering, re-interpreting and re-imagining tracks such as I'm A Believer and The Beatles' Good Morning, Good Morning. "Each song is connected to me in a very specific way," he says. "It's like an audio scrapbook."

Dolenz sat down with MusicRadar recently to talk about learning the drums in record time, his unorthodox playing style, performing amid mass hysteria, what Jimi Hendrix was like on the road, the new tour, the new album and a whole lot more.

Very few people get to achieve the level of fame The Monkees did. Seriously, how freaking amazing was it to be that big a star in the 1960s?

"From my point of view, and I can only speak for myself - you might get a different answer from Mike and Peter, and you might have from David also - I was rather isolated and secluded from it. First of all, the workload was enormous. We were rehearsing the television show 10 hours a day and then rehearsing for the tour and recording at night - that went on for a couple of years.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Until we got on the road and started doing concerts, I had no idea how successful the show and the music were. But I'd had a taste of it before on a much lower level. I'd been a child star on a TV series [Circus Boy]. I had a fan club, I had parades, and I had kids running after me for autographs. It wasn't on the scale of The Monkees, of course.

"By the time The Monkees came along, I knew the score. But nothing could have prepared me for what happened with The Monkees. That whole phenomenon really only lasted a couple of years. Then I went to England and was producing and directing television shows. It wasn't until 1986, when I came back for the reunion tour, that I realized the impact The Monkees had on the cultural landscape."

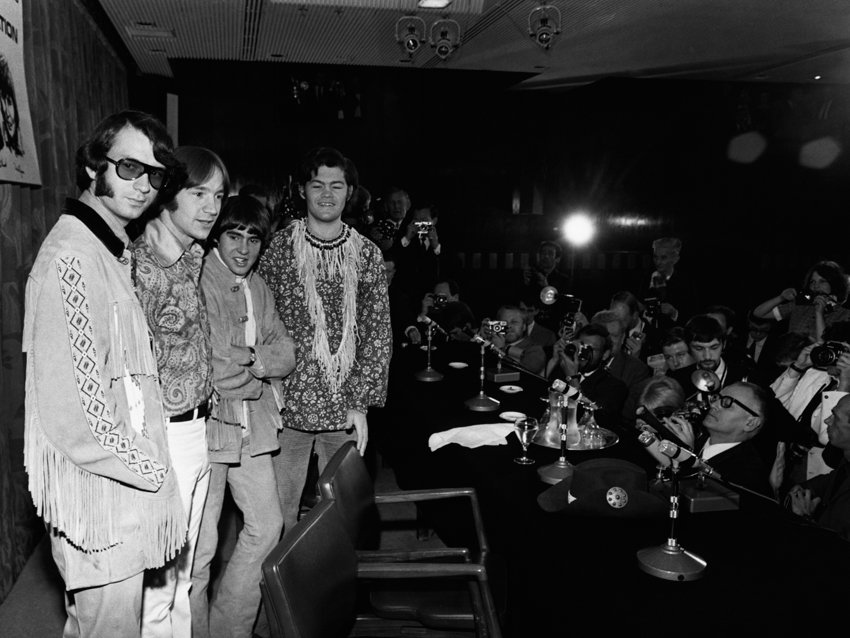

The Monkees (Nesmith, Tork, Jones and Dolenz) meet the press in 1967. © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

When you were cast in the show, you weren't a drummer. But my goodness, you learned fast. You must have studied like mad.

"I did study, absolutely. But I was already a musician. You had to be able to sing and play to get through the audition process. I was a guitar player - still am. My first instrument was a Spanish guitar. My father had gotten me interested in that, doing Segovia and Villa-Lobos and all that. That morphed into folk music, the Kingston Trio and Bob Dylan, and then into rock 'n' roll. I was in bands, playing covers.

"For The Monkees, they said they were casting me as the drummer, and I said, 'Fine. Where do I start?' Because I was a musician and could read music, I wasn't starting from square one. After the pilot was sold and we knew we had a show, we knew we'd be going on the road, so I had a period of time to learn. But yeah, I am a quick study."

Some of the greats from The Wrecking Crew - Hal Blaine, Earl Palmer - played on Monkees songs. Did you take notes during sessions?

"Oh, yeah. [Laughs] Both Hal and Earl were giving me lessons. The Wrecking Crew played on everybody's records. Absolutely, I was watching what they were doing. Hal and Earl, I learned from the best."

Was it at all intimidating? Here you are with the best guys around…

"Well, no. I had been cast as the drummer. Over the years, I've taken it very seriously. I'm working right now getting ready for the new Monkees tour. We're going to play just as a trio like we did on the album Headquarters, and I'm working every day at it. I'm doing my paradiddles." [Laughs]

To go on tour the first time, how long did the band rehearse?

"We had worked for months to get ready to play on the road. Of course, nothing could have prepared us for the event that we were presented with. Usually, you start in a new band and you play bar mitzvahs or bowling alley parking lots. I'd done that in cover bands, playing cocktail lounges and stuff. But all of a sudden, our first gig was at a 10,000-seat arena. It was very exciting... and quite daunting. On the other hand, you couldn't hear anything anyway!" [Laughs]

Much has made of the fact that the screams for The Beatles had died down by 1966, yet the response for The Monkees was pretty fierce.

"That was probably the hardest part of the job, playing without being able to hear. There were no monitors back then. I was singing leads and playing the drums - without monitors, without any help or assistance, and without being able to hear anything. I couldn't hear my drums, I couldn't hear my voice, I couldn't hear Mike or Peter or David. [Laughs] It was pretty brutal.

"There was a pretty interesting CD that Rhino put out called Monkees Live '67. You do get a sense of the insanity and the sound and us out there. We were essentially a garage band. So was everybody. You couldn't duplicate the recorded sound - there just wasn't the technology to do that."

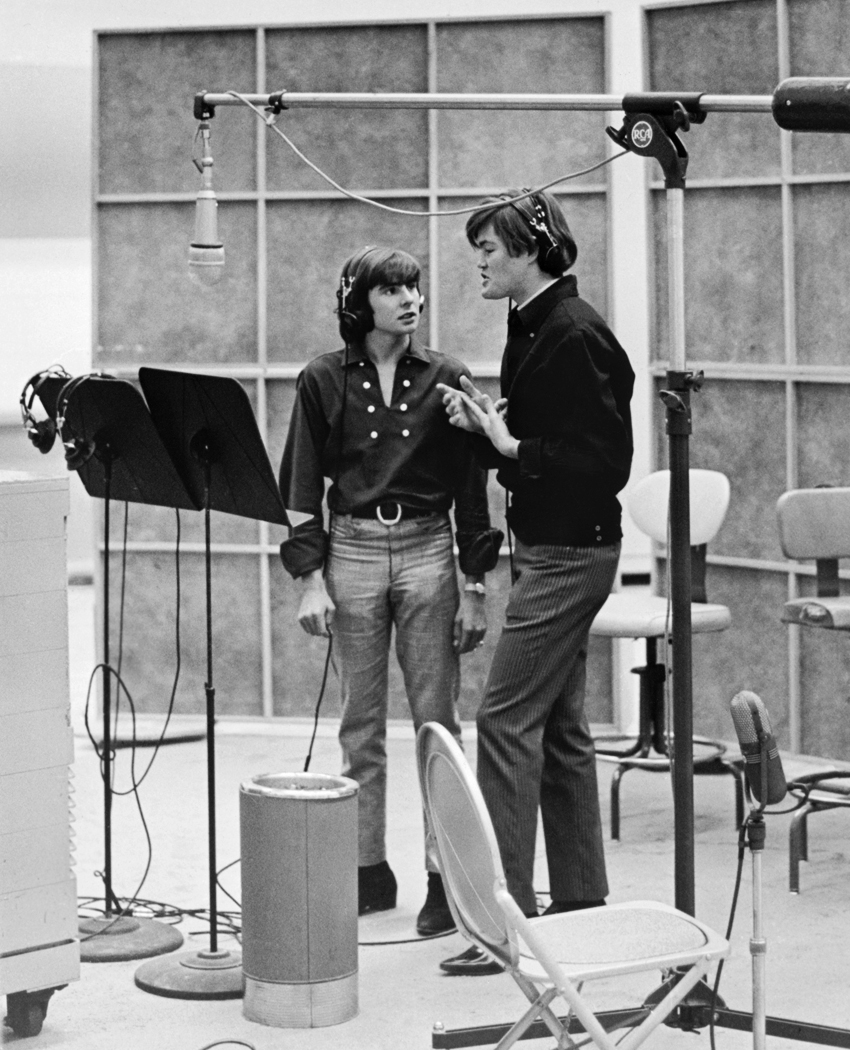

Jones and Dolenz tracking vocals, 1966. © Bettmann/CORBIS

Let's talk about your drumming style, which is quite unique. Did Hal Blaine or anybody try to "fix" what you were doing?

"Well, no. What happened was, I started taking lessons from my first teacher, John Carlos, a very famous drum teacher. But before that, when I was a kid, I had a leg-bone disease. Fortunately, it didn't turn out to be serious, but it made my right leg weak - it still is - and I'm right-handed. So this presented a problem.

"I sat down and started playing at a traditional kit, but my right leg got very tired playing the kick. I told this to John Carlos, and he said, 'Well, you're still learning. Just switch it around.' I started playing the kick with my left, which was fine, and I played the snare with my left hand and the hi-hat with my right leg. It became this sort of V-formation. That's how I learned, and it became kind of interesting. I think it contributed to some of the unique rhythms I've come up with because of that configuration."

On the TV show, you were playing both Grestch and Rogers kits. Did you have a preference?

"No, not really. The Gretsch was the first kit that was promoted for the show. When the tour came along, I played the Rogers on the road. I still have that set. It's so funny, boy, back then the hardware was so flimsy. The cymbal stands and the hi-hats… and the kick drum had this leather strap holding it together. [Laughs] But I didn't have a preference. I've been sponsored by Drum Workshop and Yamaha, and this year I think we have another Gretsch sponsorship. So you'll get the old Champagne set."

Jimi Hendrix opened for The Monkees for a handful of shows in '67, much to the shock of your young fans and their moms. What was seeing him on stage at that point like from your standpoint?

"Well, I'm the one who suggested him for an opening act. I was a fan before he was even famous - I'd seen him at the Monterey Pop Festival. I remembered being blown away by his skill and his musicianship and his style, which is legendary. On tour, we couldn't always watch the opening act because we kind of had to be smuggled into the venue. But we'd get to watch him sometimes.

"Mostly, I remember the offstage stuff. We hung out, we partied, we goofed around. We went to clubs and stuff like that. He was a lovely guy, a very sweet guy."

Let's talk about your new record. Your cover of Good Morning, Good Morning is amazing.

"Why, thank you. All the songs on the album have a story behind them, but I was at that Beatles session, so it got burned into my neural pathways. Eventually, on an episode of The Monkees, I got them to give me the rights to let me play the song on the show, which was unheard of at the time. Over the years, I sort of came up with this different take on it. But I switched the time signatures around. On the original, the verses are in 4/4 and the middle eight is in triplets. I turned it around so that the verses are in triplets and the middle eight is in 4/4."

OK, Sugar Sugar…

[Laughs] "It's hilarious, isn't it? As you know, Don Kirschner presented that as the next Monkee tune. I was going to record it. That's when Mike Nesmith led the palace revolt and we fought for the right to have at least some sort of control over the music. I didn't go to the session - I'd gone to England, and that's when I met The Beatles. Don Kirschner got fired, but then he recorded the song with The Archies. He said 'That way, nobody can talk back to me.' [Laughs]

"I mentioned this to David Harris, the producer of the record, and he said, 'Let me look at that song and see what I can come up with.' I said, 'You've got to be kidding me. There's no way I can record Sugar Sugar.' But he came up with one of my favorites, this very dark, almost Coldplay-ish version of it. It's a rude song! [Laughs] I love it. It's one of my favorite tracks now."

How was it covering yourself with I'm A Believer?

"That's a good question, as I always had my doubts about it. The way I got around it was by not forcing it. I always wanted to do a country, kind of Everly Brothers version of it. It turned out great. I'm really happy with everything on the album. And then there's Randy Scouse Git, where David Harris did this wonderful re-envisioning of it. I'm pretty pleased."

The tour The Monkees are doing is a tad bittersweet, obviously, without Davy.

"Yeah, it is."

Have you started rehearsing yet?

"We have. I've been up in northern California with Mike Nesmith for the last month, working with him, because he hasn't done a lot of this material in many years. It's a different dynamic, and as you say, it is bittersweet. We're not calling it the Davy Jones Memorial Tour, but he will definitely be remembered, and there will be an homage to him."

Dolenz behind the kit in 2011. "I'm doing my paradiddles," he says, prepping for the new tour. © Sayre Berman/Corbis

I've been reading about the idea of having Jimmy Fallon join you guys -

[Laughs] "That's a joke!"

Is it?

"It's a total joke. That was just, like, goofing. No, what has been discussed is having friends and people come on stage in select places and singing along with us. Ringo does that. U2 - Bono brings people up. In fact, Davy Jones joined U2 on stage once for Daydream Believer. So that's what that was all about. We understand that Jimmy is a fan and likes the music, so maybe he will show up on stage somewhere as a guest. But he wouldn't be replacing Davy."

When The Monkees were at their height of TV fame, there were detractors who called you nothing more than a prefabricated pop group. But then you went to England to find that The Beatles were fans. That must have been gratifying.

"Well, yeah, you're right. There were people, especially in the early days, who just didn't get it. But quite frankly, when you're that successful and that rich [chuckles] and that famous, you just don't give a shit! [Laughs] I'm sorry, but that's the truth. But you're right, I don't know why that happened.

"In England, they just got it. The Beatles got us. John Lennon said, 'It's like The Marx Brothers.' They got the whole dynamic, the whole sensibility. There were others. Frank Zappa, he was a huge fan. Lots of people in the business got it. Some of the journalists, quite frankly, and even people to this day, there's still some people who don't get it."

I always thought there was a big pop art aspect to The Monkees.

"Absolutely. There was, totally. It was almost like installation art. Performance art!"

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.