5 songs guitarists need to hear by Andy Summers with The Police

From punk energy to jazz chops; modded vintage Teles to guitar synths… and no Every Breathe You Take in sight

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On paper, The Police were an odd proposition. Emerging against the backdrop of London’s late-'70s punk scene – a world Summers described in his autobiography as “a maelstrom of mohawks, Union Jacks, bovver boots, latex, fetish gear, and amphetamine-driven music” – the angular fusion of pop, rock and reggae that became their signature sound shared the same energy as punk, but was built around a musical virtuosity that was in complete contrast to it.

Yet thanks to world-conquering songwriting backed up by their intense musical chemistry, the three pouting blondes that made up this unique-sounding trio managed to keep their simmering antipathy at bay for long enough to capture and distil a sound that sold in excess of 80 million records.

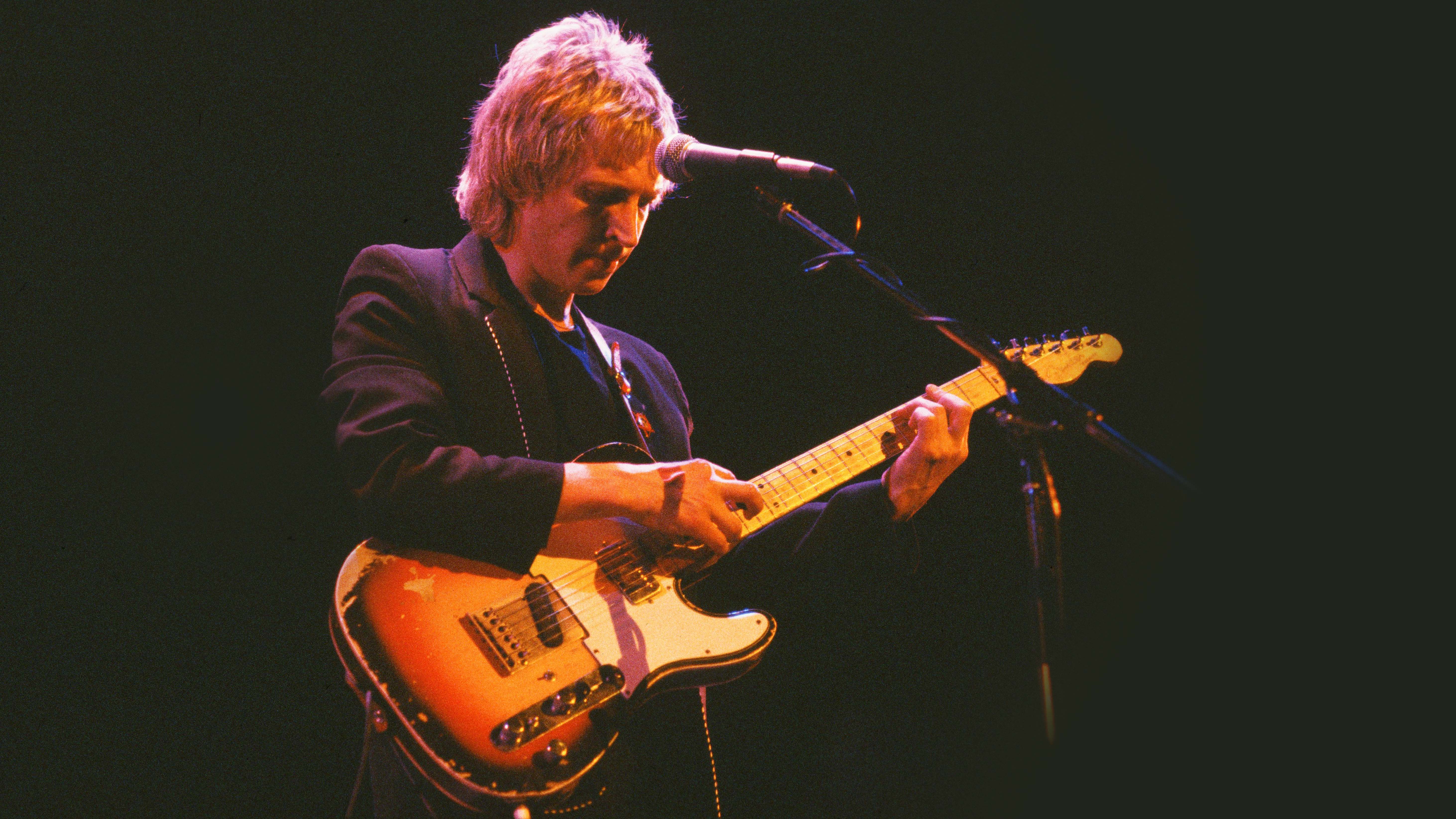

Andy Summers was already in his 30s by the time the trio found success. He’d been introduced to the guitar in the mid 1950s aged 12 and played obsessively ever since, going on to forge a reputation on the London electric-blues scene of the 1960s. Playing with the likes of Zoot Money, Soft Machine and Eric Burdon’s Animals (listen to the cover of Traffic’s Coloured Rain from Love Is for a stunning four-minute solo), he sold his ’59 Les Paul to Clapton for £200 and was the first guitarist Jimi Hendrix encountered when he visited London in September 1966.

Summers then studied classical guitar in Los Angeles before returning in 1972 to record and tour with an eclectic bunch of high-profile solo artists including Kevin Coyne, Neil Sedaka, Joan Armatrading and Mike Oldfield before he finally joined ex-teacher and ditch-digger Sting and son of a CIA secret agent Stewart Copeland in The Police, as a replacement for their guitarist, Henri Padovani, in 1977.

Any guitarist who can take classical, electric blues and jazz influences, reggae’s rhythms, punk rock’s energy and the Roland GR-300 guitar synth, put it all together and somehow make it all work must be some kind of genius. Yet Summers himself has said that his sonic experimentations were born out of necessity: “Being in a trio and having to be onstage a couple of hours a night playing through all these songs, I needed to open the sound up and keep diversifying it throughout the set,” he told Uncle Joe’s Garage. “I was interested more in a palette of colours.”

These fearless experiments with new pedals in fresh combinations would lead to some of the all-time most memorable guitar-effects moments and the band’s biggest hits, too.

Since The Police disbanded, Summers has pursued his lifelong fascination with guitar playing, releasing over 30 records. To get acquainted, you could try the bookends of I Advance Masked, his 1982 solo collaboration with Robert Fripp released while he was still in his main band, and Metal Dog, Triboluminescence and Harmonics Of The Night, his recent trilogy of solo records.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

For anyone unfamiliar with his work, here are five Police songs that show just a few facets of one of the guitar’s most eclectic pioneers…

1. Message In A Bottle (Regatta De Blanc, 1979)

Regatta De Blanc’s first single is based around a guitar riff that was written by Sting. “I used to play it over and over again to my dog in our basement flat in Bayswater,” the singer wrote in Lyrics By Sting. “He would stare at me with that look of hopeless resignation dogs can have when they’re waiting for their walk in the park.” However, Andy Summers’ sleek interpretation of it is a prime example of the guitarist’s sophisticated chordal approach in The Police. “Sting showed me the riff he had, but I embellished it,” Summers told Guitar Player. “I had the chops to make it swing and rock… I was thrilled to have something that started to progress our style.”

Moving away from the traditional rock-guitar approach of full bar chords using all six strings, he would instead strive to substitute more musically ambitious – often arpeggiated – alternative voicings and riffs to spell out a song’s progression more obliquely.

The Add9 chord at the heart of the song’s main riff is a movable three-finger shape, and the ability to move it either along or between strings while retaining the same claw-like shape makes the motif’s circular, fluid motion possible.

Once you’ve mastered it, you’ll find it so simple and addictive we guarantee you won’t stop playing it… at least until your left hand cramps up, that is, so pace yourself. Add to that an off-kilter harmony part on top of the double-tracked main riff and the howling, Gilmourish guitar solos smuggled throughout – not to mention the judicious use of filter effects recalling the sound of ocean waves – and you have a guitar performance that sounds deceptively simple on the surface, but reveals hidden depths the more you listen to it, especially when isolated.

In his autobiography One Train Later, Summers said: “For me, it’s still the best song Sting ever came up with and the best Police track.” Sting agreed, telling Jools Holland it was his personal favourite, and it was the band’s first UK No. 1 single, too… who are we to argue?

2. Walking On The Moon (Regatta De Blanc, 1979)

Summers famously added the magisterial dampened arpeggio part to Every Breath You Take in the studio at the last minute, dashing off his most famous and timeless guitar part seemingly effortlessly, to a round of applause from everyone present. Yet it’s the echoing central riff of Walking On The Moon that will ring out forever over the airless lunar landscapes of guitarists’ minds.

True, the subject matter of the song, the sparseness of the arrangement, Copeland’s use of a Roland RE-201 Space Echo on his drums and Sting’s gravity-defying vocal melody perfectly set up the spacey atmosphere. However, it’s that sustaining, filtered Dm11 chord with its ghostly single repeat that makes the song’s motif so unforgettable.

Live, this would have been recreated by an Echoplex set to a single repeat, along with various effects from Summers’ custom Pete Cornish pedalboard (an EHX Electric Mistress set to a chorus-y sound and maybe volume swells) in combination. For the recording, engineer Nigel Gray recalls the guitarist using the Surrey Sound studio’s ADR Scamp S24 ADT analogue delay with flanger rackmounted unit, for its inimitable glassy tone.

3. Driven To Tears (Zenyatta Mondatta, 1980)

Has a more varied selection of guitar parts ever been crammed into three minutes (or thereabouts) of what was an otherwise unremarkable album cut? Like Bring On The Night on the album that preceded it, Zenyatta Mondatta’s Driven To Tears is a bona-fide demonstration that the musical palette Summers was using had way more colour and variety than that of pretty much any other guitarist at the time.

Exhibit A: the Echoplex’d and chorused, or at least modulated, chord washes in the rudimentary chorus section of the song. Suddenly, these give way to an arpeggio part and scrabbly tremolo picking, which in turn metamorphosise into Exhibit B: a jazzy Robert Fripp-esque wide-intervalled solo that sounds a bit like one of those crazy warm-up exercises shredders do, but somehow works in this context (a style he explored more on 1981 B-side Flexible Strategies).

“I’m pretty sure I used my Telecaster,” Summers recalled to Guitar Player. “I had my amp on 11 for the solo – it was really loud, because it sounded appropriate for that sort of dissonant, chromatic solo… it had to be something angry because of the lyrical content, which is basically about war and suffering.”

Then it’s back to the ominous right-hand-dampened riffery and colourful washes of delay-soaked chords for a little while before Exhibit C – ultra-precise funk rhythm of the kind also showcased on Ghost In The Machine’s Too Much Information – plays us out.

Elsewhere on the same album, the Summers composition Behind My Camel – at heart a relatively simplistic Frankensteining of dark and brooding guitar and synth tones – somehow won the 1982 Best Rock Instrumental Performance Grammy Award, no less. In contrast, Driven To Tears showcases his road-honed playing to perfection, pulling together a blend of contrasting and contradictory textures and styles into an energetic whole, through sheer force of will.

4. Demolition Man (Ghost In The Machine, 1981)

Summers’ playing in The Police may have had a pre-meditated and cultured quality at times, but he was also an adept improviser. This one-take song was the first track recorded for Ghost In The Machine, and showcases Summers’ background as an accomplished blues-rock player on the '60s London scene.

The near-six-minute romp – a song Sting originally penned for a Grace Jones A-side – is graced by a near-constant stream of Cream-like soloing, frustratingly low in the mix. Summers puts his famous red early '60s Stratocaster through its paces via a comparatively straight-ahead, sustaining edge-of-feedback blues-rock tone, clearly enjoying being able to give his vibrato arm a fair yanking.

He still remembers to mix up the major and minor pentatonic flavours and dust off the rock ’n’ roll doublestops for any blues aficionados with their ears pressed against the speaker cones, though. The band’s roadie Danny Quatrochi played bass because, according to producer Hugh Padgham, Sting’s original take had been recorded while bouncing on a trampoline and was therefore too sloppy.

5. Secret Journey (Ghost In The Machine, 1981)

On the preceding track in the album’s running order, Omegaman, Summers had a breakthrough with his guitar synth, resulting in the song’s dissonant, resolving figure and hypnotic solo. But with Secret Journey, Summers put Roland’s G-303 and GR-300 guitar-synth combo to a more ambitious and epic use.

“Into the intro to Secret Journey, I’m playing these strange chords, with the synth tuned in fifths, and you get this sound, with echo and chorus on it," Sting old Music UK in 1981. "And also, against that I played some very weird stuff on a Strat, so you get this great sort of cloud effect until the riff actually starts coming in, the riff sort of fades up through it and then the song starts. Then it shuts off [claps hands] like that in the middle and then you get wahhhhhhhhhhh… the sound of the Himalayas comes in. It’s good.”

As a middleground between by-now-familiar Police-isms and a confident foray into fully experimental territory, Secret Journey – its chorus section like a future echo from one of Coldplay’s arena-filling offerings – represents an intriguing potential direction the band could have headed in.