Tyondai Braxton (and colleagues) on performing and recording with his amazing modular setup

The experimental New York composer tells us why he went from chords to cords on sophomore album, HIVE1

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tyondai Braxton has been part of the modernist conversation since the early 2000s, first as guitarist and singer in math-prog-indie-rock band Battles, then as a composer of electroacoustic orchestral hybrids performed from New York to Australia. Unwilling to remain static, Braxton parlayed his exploration of first guitar pedals then Ableton Live tone-sculpting into a compilation of Eurorack-format synthesis modules. Introduced at an early age to the works of composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen and Morton Subotnick, before falling in love with Nirvana and Sonic Youth, Braxton set out to subvert this new generative instrument.

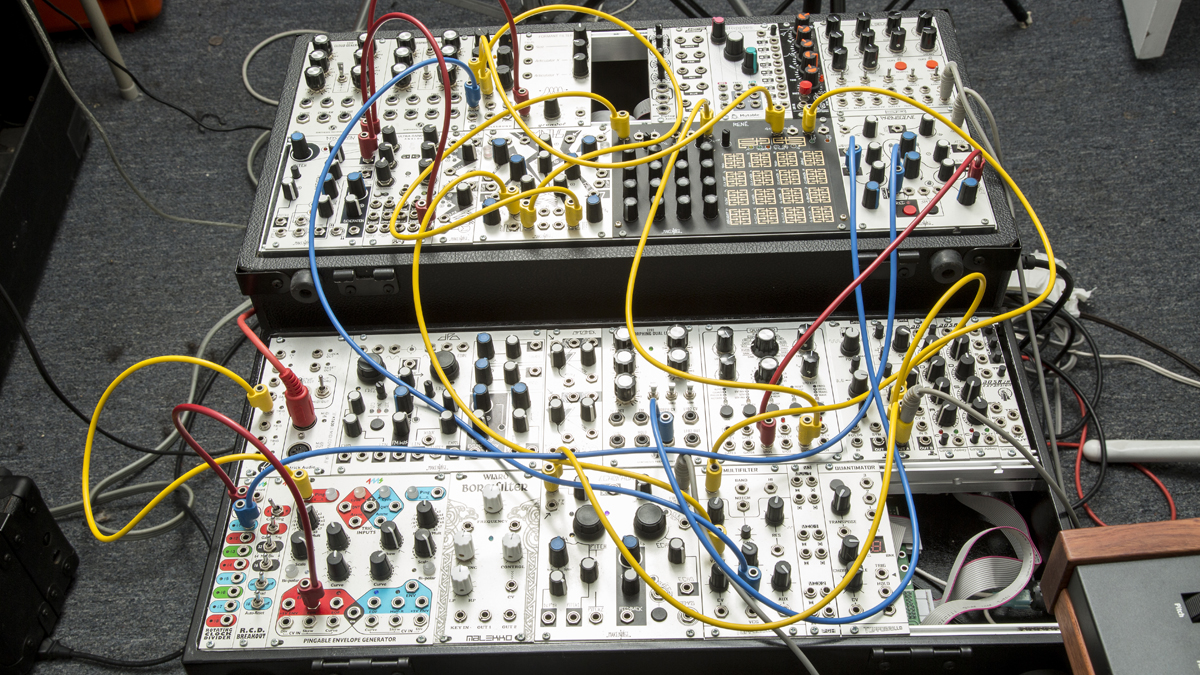

In 2013, Braxton staged HIVE, a surround sound installation at the Guggenheim Museum featuring two Eurorack cases - a few dozen modules in total - accompanying three percussions. Situated in architectural 'pods', the five musicians wove together Braxton's notation into an ecstatic yet controlled suite of pitched, pinched and reverberant synchronicity. At the same time, Braxton started recording as he turned trilling algorithms into crystalline tones and thick energy.

We spoke to Braxton, as well as others, about reconciling the modular synthesis learning curve and preparing HIVE1, which he lovingly calls "a very edited version of a series of mistakes going together".

Tell us about your relationship with both sound and music, and when you were able to distinguish between the two…

"I've always been excited about things I don't understand, and for sound design it's exciting to appropriate sounds you just hear in the world and organise them in a way where there's real intention. I started more on the side of appreciating what you'd consider traditional Western music; what people understand to be musical. And then over time I started to realise you can incorporate, affect and create sounds outside of what's harmonic. It's taken my entire life to figure out those relationships and find ways to incorporate textural, organic sounds like that in my music in ways that are still musical and organised."

What was the first tone you discovered that helped you define yourself?

"In high school, I bought a Boss PS-3 pitch shifter/delay, and I started to find who I was through what I could bring out with that pedal, through manipulating the guitar in that way."

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

That's a pedal that can modulate from clean delay to inverted noise, and can definitely produce as much physicality as it can musicality. Do you draw a direct correlation between that foundation and your recent explorations of modular synthesis?

"You're catching me at a transitionary time. On the one hand, working with Eurorack stuff sends me back to the teenage feeling-in-the-dark sensation again, and at the same time it seems like a logical extension of the work I'd done, which included Ableton Live and Max for Live. Ableton is still the brain of how I'm working right now, but the Eurorack unlocks so much for me in terms of a tactile search for a new mass of sound to conquer. I just hoped to be able to get to a point of control with it where I could find something for and of myself.

"Modular isn't just like learning an instrument, though; it's not like having guitar pedals, a looper and adding a Juno synth. It's a completely different way of thinking about music, which opens its own can of worms in terms of aesthetics, how to find yourself. So for me to give myself to that process meant letting go of some other things I'd learned to that point. The Eurorack was where I started from for writing HIVE1, and it took a good year and a half to really internalise the depth of what this instrument can do."

What was the corner you turned following your last album [2009's Central Market] that prompted you to pick up your first module?

"It kind of turned out to be an actual corner. I had been thinking about this instrument and picking up some modules for a while, but it seemed very intimidating and expensive to learn about these abstract things that might not even work. As a coincidence, two blocks away from where I live in Brooklyn this modular store opened up, Control, and I could walk over and try stuff, have them explain to me the principles, the fundamentals of modular synthesis. So that was an incredible resource and I first picked up some modules from this company, Make Noise. I got this dual oscillator, the DPO. And I think I got a Malekko Borg filter and a 4ms Pingable Envelope Generator to try really basic things. And when I first plugged it in, it was a game changer to know you could think about sound like this."

When did you first feel that the chain was coming together to not just produce a tone, but the potential for composition?

"It took me a long time, man. I still have this war within myself that there is this idea that the strength of the modular is that its level of expressiveness exists far outside a human's ability to notate for it. It has its own language, so what you gain in that expressiveness you lose in a kind of control. It took me a while to allow myself to almost feel like I was curating an idea rather than playing it. It's relinquishing a certain amount of performance to show a way forward with these building pieces."

For all that potential chaos, however, the album shows compositional motifs and concepts of minimalism as part of the methodology…

"That was the goal, to say, 'How can I interface this instrument with the things I know and love about music? How do I interface worlds that seem so different?'. And by the end, I felt I had enough of a grasp on how the modular works to get it to do what I wanted, while leaving room for surprise. And I hope people listening to the record can hear there are very controlled elements of it and each piece is very considered, how it unfolds, how it's paced. Not like an orchestra piece, but it is informed greatly from that way of thinking.

"The first incarnation of the performance vehicle, HIVE, the five glowing pods with three percussions and two modular synths that started this whole record, was me asking, 'What does it mean to compose a percussion ensemble piece interfaced with modern electronic music?". But the thing I didn't realise with the modular was how long it would take to master the instrument and reconfigure my way of thinking about making music with modular equal to percussion, not just something mixed in."

So what's the rosetta stone for cracking the modular language?

"The level of control and sophistication you can gain by using LFOs to generate sequences within the modular was a huge revelation to me… The idea of sending imperfectly shaped LFOs to sequencers that can read the shape, like the Make Noise René, which allows you to outline control voltage with its 4x4 grid and send awkward shaped LFOs that cause it to be reset constantly. It's technical, yet so awkward and weird, and sounds like something I would do with guitar… So that's when I realised that I was going to be able to find myself in the way I was working and I was going to be able to extend my understanding."

Daren Ho (Co-owner, Control): "With a typical sequencer, you have it going back and forth, penduluming, but with the René you send in that LFO and depending on where the voltage is sending determines the position of the sequencer. So, if you have a sine wave you'll get an even sequence that goes from the first step to the 16th and back down once the wave completes its cycle but, because it's curved and not straight like a triangle wave, it will have bizarre timing that doesn't necessarily fit in traditional Western notation. If you use the triangle, you'll end up with something more consistent, more regular 16th notes constantly changing. But using wavetable synths, which Tyondai has, you're mixing the waveforms, so if you mix a sine wave with a sawtooth wave, it will act like one for a second and then the other. It gets crazy. And the wavetables are digital, so you can load different waves that, depending on the designer, can be inspired by rhythmic stuff or based on models of other synthesizers, so you have weird abnormalities, tapers, noise elements and crazy variations."

TB: "Going into the depths of how violently you could cycle things let me bring it back to a point where I could notate percussion around it and alongside it, as opposed to notating the parts first and trying to shove the electronics in after the fact. But the modular is just the principal of a lot of tracks, with other elements on top of it. The careening sound swells that cascade up violently over and over on Boids, for example, are a sample of my guitar that is passed back and forth in the Max for Live granulator. I also used a Dave Smith Instruments Prophet 12 for some featured synths; it has an amazing level of modulation and crosstalk I used for pads and some bizarre sequences.

"The percussion is all close miked, so like the modular, it's very upfront. I first approached the music as performative, as opposed to conceptual editing, so when we did take it in the studio I wanted something visceral, offering a physical experience first, so it didn't get lost in cerebral theory. I did swap out a lot of small percussion for electronic soundscape pieces, but the sense of environment remains up close and personal."

Elsewhere on MusicRadar

The A to Z of Eurorack modular synths

Round-up: Eurorack modular filters

How to create a modular compressor

Free music samples: download loops, hits and multis

"By the end I felt I had enough of a grasp on how the modular works to get it to do what I wanted while leaving room for surprise"

When did the performance end and the recording process begin?

"As I was learning the instrument, I was recording nonstop, capturing everything using Ableton and my modular routed into the RME Fireface UFX to my laptop. I have an API Lunchbox as well, but I kept things simple while tracking my experiments, so I could learn from them. For the percussion notation I use a program called Sibelius, and I'd take a mock-up of that notation and import it into Ableton. All that was done at home, but for the live percussion we went to Flux Studios in the East Village, where we recorded

to Pro Tools with Damon Whittemore."

Damon Whittemore (Owner/Engineer, ValveTone Recording): "We essentially established the same three percussion setups they did live with some tall baffles in between them that contained glass windows, so everyone could have line-of-sight, because they were performing off written parts and there are a lot of parts that are synchronised. The key was not to have too much room sound, to keep them in the same space as the modular parts.

"We had a lot of classic small diaphragm mics to capture the really quick transients of everything - Neumann KM 86s, Shoeps MK4s, Neumann KM 84s - plus some medium-diaphragm condensers for the snares and a Neumann U47 FET for the concert bass drum. We were capturing layered parts, how they became almost machine-like, with dynamics played with such precision and timing that it almost doesn't sound like a human can do it, and the studio has a beautiful Neve 53 series early 70s console that was fabulous for that. I prefer to record flat and get the sound by mic choice and placement along with those preamps."

TB: "After we recorded the percussion, we went out to play some shows, then I took the sessions back to my studio and started editing them. It's funny what your intuition brings to you when preparing for a live performance; then, when you're actually sitting in front of it as a record and thinking of how best to experience it, you reconsider some things. I'm definitely a nudger, a guy who is always poking at the timeline and has a hard time leaving things alone. I like doing that: toying with things, seeing what works best, considering if the pace of events is happening in the best way."

Given your appreciation of composers from Edgard Varèse to Philip Glass, did you place a value on negative space alongside repetitive structures?

"I think about that a lot. It goes into a larger conversation of what it means to have polarity in what you're doing. Loud to quiet, dark to light, space compared to density. It's a powerful, interesting experience when listening to music. It's something I don't hear a lot of people do, because in some ways it's not appealing to an audience that may want momentum throughout, but I really love the idea of these ions of activity and then nothing."

Composition can be a very additive process, but was mixing?

"The quality of sound coming from the modular made me very conscious of the placement of things; it's so detailed, it allows you to be surgical. Then it was back to Damon for final mixing."

DW: "For mixing, we were at ValveTone Recording, my studio that shares a building with Flux. And for the mixing stage, it was mostly subtractive EQ. There were a few sounds that he brought in that maybe needed to have some low-end rolled off and a little bit of interesting mid-range brought out so they'd be differentiated, but Ty has extremely good ears and the sessions he'd bring in to mixing usually were in a way that was pleasing to him. The intent was there, it was just a matter of setting the relative prominence of elements and balancing points where the live percussion and the modular both had a cutting quality.

"We used the Dangerous BAX EQ, GML 9500 EQ and Dangerous Music Master, a nice stereo whip enhancer. We'd switch out some digital things on the aux for something outboard, like a Bricasti M7 MkII Stereo Reverb Processor or an AKG BX 10 spring reverb. But probably the place we spent the most time was doing subtle pan automation to give a sense of motion, or I might lower something in volume, accentuate its pan and then add reverb to get three-dimensional depth, make it seem like it comes from back of stage to front.

"The signal chain was Pro Tools, the Lynx Aurora 16-VT converters, and then summing through either a late 70s Neve 5465 if I wanted to warm up or slow down the transients, or a Dangerous Music 2-Bus to keep things super quick, wide and transparent. And we had the API 2500 on the final stage to enhance the rhythmic insistence, get just the right emphasis on accented beats; but we were never doing more than .5 to 2dB of compression. Some moments he wanted you to feel your speakers were exploding with washed-out, intense sounds, but if you compress too much you're going to lose that drama, because everything before that moment is loud and it has nowhere to go. So it was probably mixed more like an avant-garde classical record in that respect."

TB: "I was conscious that I wanted to preserve the dynamic range of the sound, so there isn't a lot of compression smashing the mix. But there were elements that sounded bright and, because it's not a dense record, there were also spots that sounded thin, so we ran it through the Empirical Labs Fatso to get a dark quality and grit."

DW: "The Fatso was used for harmonic distortion, its tape emulation properties. And the main A/D to capture the mix back was a Crane Song Hedd-192, using a little bit of its tape and pentode settings to make sure there was a lot of information, a lot of frequency range."

Now, having had time to evaluate your synth modules in various circumstances, how do you feel they interact? Is it more a dance, a dialogue, a soliloquy…?

TB: "I really love that machine and the way it has its own life and logic. I was trying to get a great new perspective on making music, and I did. But I also will say that it is just an instrument. It inspired and confounded me, added a tool to the chest. Every one of the orchestras and ensembles I've written for has an electronic element and, while mostly with those guys it was Ableton Live, now I feel I can integrate the modular, or samples of it, in a deeper way. But I realise that I first imagined it would be this thing that would change so much, and at the end of the day it's just another way, not the only way or making things obsolete."

Will you reroute your workflow again for your next record?

TB: "I will say that with the Prophet 12 right now, it's great to just sing and play again. Having a much richer understanding of these instruments means when I'm interfacing with the Prophet 12 I'm understanding more how to tweak and destroy and modulate it, but also just playing chords and pads.

"The next project I'm working on is a lot of notated material for a really large ensemble, and it's going to use a lot of the things I've learned with the modular. But it's not going to be generated by the modular itself. The record I did before HIVE1, Central Market, was orchestral with a heavy electronic element. So the way I feel now, I don't know if I'll ever not be excited hearing electronics interface with acoustic elements, but the polarity is shifting to seeing what I can do to bring electronics in a more sophisticated or subtle way to orchestral work."

HIVE1 is out now via Nonesuch Records. For news, live dates and info head to Tyondai's website.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.