Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As one half of UK dance legends Groove Armada, Tom Findlay has collaborated with and remixed artists as diverse as Will Young, Madonna and A Tribe Called Quest.

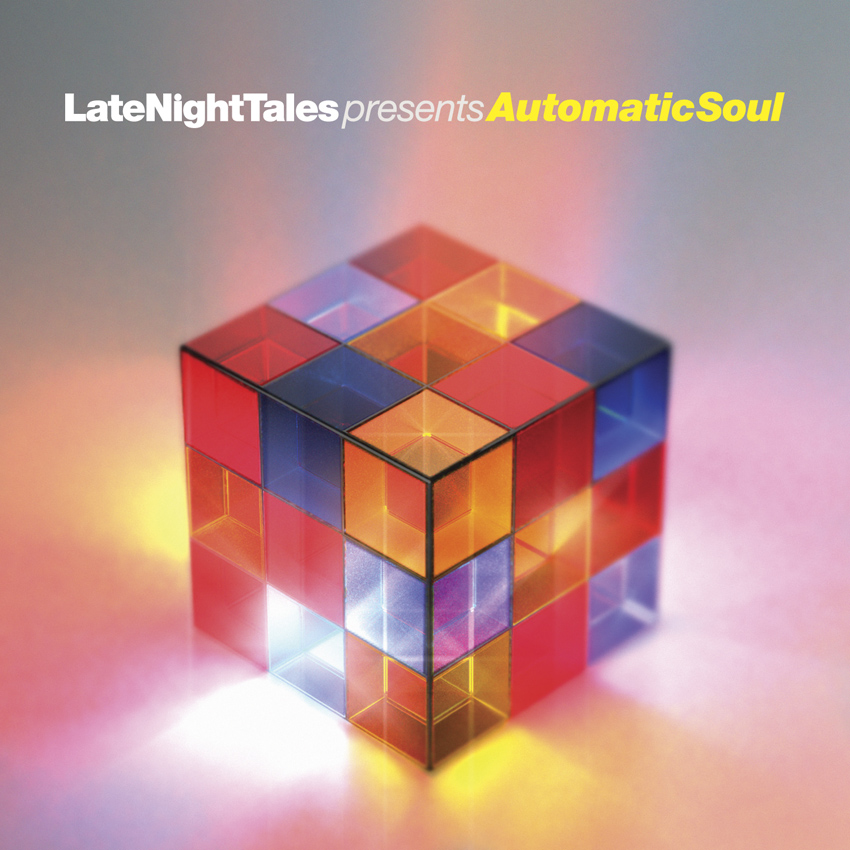

His latest project, Late Night Tales present Automatic Soul, is an album of re-edits focused on the sweet, sweet sounds of '80s funk and RnB, including new twists on classics such as Mtume's Juicy Fruit, Bits and Pieces' Don't Stop The Music, and Meli'sa Morgan's Fool's Paradise.

For the uninitiated, a re-edit is a rearranged version of a track that's typically created by chopping up the stereo master. Unlike remixes, re-edits don't usually add new elements to a track, and are intended to make a track's structure more DJ-friendly rather than reinvent it completely. Because a re-edit can be created without using the original stems, there are thousands of unofficial examples available online, with funk and disco tracks being particularly popular re-editing targets.

We caught up with Tom to find out more about the project, and learn more about the esoteric art of the re-edit.

What makes a track ripe for a re-edit?

"When you've just got really simple, lovely, chuggy grooves... you just need to get eight bars of pure groove and then you can have fun with it!

"With a lot of these tracks you can really hear where dance music came from. Tracks like Fonda Rae's Touch Me, which is the kind of era where disco turned into house. The '80s black music scene with drum machines and technology is a lovely period. You get the juxtaposition of these grating, tough drum machines that were recorded onto tape so they sound really fat, going back to back with some real soul music and old synths.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"So yeah, it's a really important era for me, I really love it. I love a nice pad, I love a good drum machine, so it all works for me!"

What were the challenges you faced on this project?

"It was one of the easier ones in terms of blending and editing. I worked with a guy called Paul Morris who is the in-house Late Night Tales engineer - he sort of pulls things together and smooths the rough edges, and he's a total whizz with Ableton Live so we did most of the editing in that. He's really dynamic with it, and really smart with the way he uses Live - I learnt a lot off him just watching him do that.

"That era of music, it's pretty tight, you know. It's probably recorded onto tape so it's not absolutely super super tight, but because there are drum machines and a certain amount of sequencing going on behind the music, the mixing was a lot easier than it was on the other Late Night Tales album, where I was trying to get Depeche Mode working with a house record!

"We tried to avoid timestretching as much as we possibly could. We really tried to avoid getting Live working much at all - I didn't want to 'over-warp' it. The only bits we'd really process in a deliberate way in Live were the crossover points where you'd go from one track to another. So there's just a little bit of basic warping and then, in a quite detailed sort of fashion - moving snares and stuff around to make them sit with the track before, and editing around those mix points. All mixing really is about flow, isn't it - trying to keep everything rolling in the right sort of way. I think we did that quite successfully. It's almost too slick; that's one of the things about Live - it actually makes things a little bit too smooth at times!"

How did you decide on the track order?

"A lot of things came into it, but you start from the DJ perspective. I imagine it like a party, really - what tunes would I want to drop? Then what's in your mind is making it flow, and making it feel exciting for the listener. It's a kind of instinctive thing - you get to the point where you realise you need a vocal... but sometimes it's impossible to make one thing blend with the other.

"The easy thing about this album is that everything is sort of oscillating between 100bpm to 112bpm, so it's a lot less challenging than some of the mixes I've done in the past!"

There are lots of complex chords and melodies in this kind of music. That must have been tricky...

"Lots of times you can make that work in quite clever ways - you can find crossover points where maybe where you've got the drums from one track and you're mixing it with the bassline of the other, and it gives you a nice little harmonic lift as you drop into the track. It's good not to be afraid of those moments of genuine uplift - you need to fight that tendency to make everything smooth.

"There were some bits where Paul did some amazing bits of looping and stuff - he's really really super smart, the way he edited filters and stuff. Compared to the 70s one I did before, where nothing was sequenced, this was a doddle, really!

Did you add anything to the tracks?

"If anything we lost stuff! The versions I like tend to be the longer ones I've got on 12", so it was more like we cut out a bit of the flannel, and sometimes we lost a few bridges here and there which didn't feel like they were doing the music any favours... being quite brutal about losing a verse and keeping the flow.

"Juicy Fruit, the opener which everyone knows pretty well, was edited fairly heavily. With the better known ones we were a bit looser with them - we took more risks with the way that we edited them.

"As much as possible, though, we were starting from the point of having the old 12" mixes which were seven or eight minutes long anyway, so they all had great grooves, and we favoured the groove elements over the verse/chorus elements of the track

"The way we were editing in Live, there were bits where you were in the mix and you'd have a certain amount of energy, and you'd want to keep it rolling for a while, so there are definitely bits where the hi-hats from one track are rolling for a minute or two over the next track. There's quite a lot of that going on because you want to keep that energy going as much as you can."

Did you find any of the arrangements difficult to work with?

"This is all sort of stuff from the post-disco edits sort of era so, at that time, the 12" was a fully developed concept. People were already stretching out the grooves. If anything, it was like leaving a bridge here and there where it felt like it was getting too fussy. So, I'd be more likely to lose a bridge or a verse than I would the opening 32 bars of the groove! That would be the sort of thing I wanted to keep in as much as possible."

Was the source material all studio masters, or did you have to source some tracks from vinyl?

"Mostly, we went to the effort of getting masters out of the studio, but there were two or three where we had to take them off vinyl - songs that have been effectively deleted, where you can't license them, and there's no one to contact! You try to find those people, but if they're not out there, they're not out there. With things like You And Me Tonight by Aurra, we had to pay £50 to have these tapes "baked" which was a new concept to me - the tapes need to be heated up or something to make them function. It was a real quest to get that one!"

Automatic Soul is out now on Late Night Tales.