How to record virtual and live instruments more smoothly by taking stock of your DAW's sample buffer

Latency on your plugins and audio recordings can derail a developing musical idea - but if you get a handle on managing your sample buffer you’ll have a much smoother ride

PLUGIN WEEK 2025: The sample buffer is one of the dark arts of the digital audio domain. Ever got up to a microphone, started to record a vocal take, and found yourself hearing a delayed signal coming back at you? Or, perhaps you are playing a virtual instrument, with an impressive delay between the triggering of a note, and the sound emitting from your speakers.

Both of these scenarios relate to the sample buffer, but with some management, these issues can be improved or even eliminated!

The sample buffer is a setting which is controlled by the user, designed to influence the amount of time being set aside for your computer to process audio. It affects the signal as it enters your system, normally via some form of audio interface, before the processed audio is returned to you for your monitoring pleasure.

Your computer is doing an awful lot of processing while recording digitally. As your audio is inputted or processed, your computer is fighting furiously to crunch the signal into digits.

This number-crunching takes a short amount of time, creating a delay to the signal which is described as latency.

This can be managed, but regrettably, you are never going to completely eliminate latency from your system. You can also employ workarounds to achieve the best results.

One day of course, computing technology will be so powerful, latency will be negligible - but we are still some way off from this benchmark.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

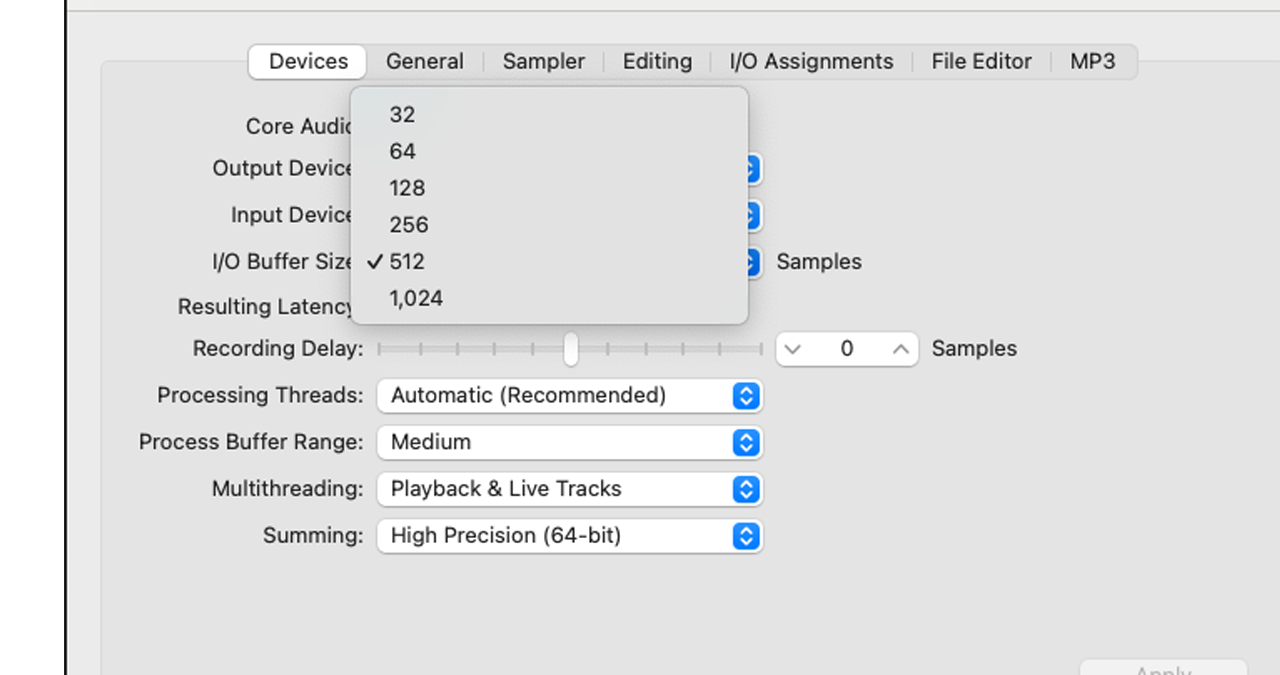

The amount of induced delay in the signal, is assigned via the ‘sample buffer size’ setting. You will find this setting in one of your DAW’s setting or preference panes, described as something like ‘I/O Buffer Size’, with an accompanying drop-down menu relating to the number of samples being set aside for the processing buffering.

Most systems will offer you half a dozen or so numerics, ranging from 32 samples up to 1024 samples. The lower this number, the lower the amount of latency, whereas a higher number will induce large amounts of latency.

In real terms, this means that the lower value is affording less time for the computer to process the data, where as a larger number affords the computer to more time.

So which option is best? It could be tempting to choose the lowest buffer size value available, which will in theory generate the least amount of latency. That is undoubtedly the case, but in reality you are likely to experience instability. This could range from glitching in your audio, to your DAW exclaiming that it does not have enough processing power, before bringing your song to a shuddering halt. In the worst case scenario, the DAW might even crash!

It is therefore in your interest to select a value which strikes a happy balance between latency, and giving your computer less reasons to grumble.

Knowing which buffer size to select depends on a couple of factors. The primary influences will be your package and the speed of your computer. More up-to-date/faster computers, will be able to cope with a lower buffer size, but before you rush to the computer store to purchase the most up-to-date machine you can afford, the size of your project will also affect how the buffering performs.

When you start a project, you are likely to spend most of your time tracking-on, either from audio or instruments in the software domain. It therefore makes sense to set your buffer size as small as your computer can handle, without interfering with your working practice.

As your project increases in size, and hopefully nears completion, you will likely enter the phase where you begin to think more about your mix. At this stage, you may add more plugs and effects to the project, meaning that there is more audio processing for your computer to undertake. So it makes sense to increase the buffer size at this stage, so that your computer can handle the increased processing of data. The short delay between hitting the ‘play’ button and hearing your track start, will be largely unnoticeable.

As we hinted earlier, there are also some workaround solutions which may help your cause. One of the most useful and effective relates to the recording of audio.

When you purchased your audio interface, you were probably directed towards the company website to download the latest drivers for your product.

As part of this process, you may have been advised to use a software product alongside your DAW, which looks a little like a mixing desk.

Thanks to some clever software engineering, most companies have a solution which provides an exceptionally low latency signal path, working alongside your DAW.

This means that you can monitor your live audio through the interface software, as you record, without the annoying delay coming back at you.

You will however have to mute the ‘live’ channel in your DAW, otherwise you’ll hear the signal twice!

Normally, the accompanying software just springs into life, the moment you start work, and it's a good idea to embrace this working practice, as you’ll achieve better results using this 2-step solution.

Meanwhile, if you find yourself working with virtual instrument plugins, you are entirely at the mercy of the buffer size.

This can be immensely annoying, particularly when working with larger orchestral sample libraries, which are renowned for inducing large amounts of latency, especially in complex legato string patches.

One trick-of-the-trade is to employ a keyboard which has an inbuilt sound engine.

By engaging an internal sound from your keyboard (such as a basic piano) it will act as a musical counterbalance to your delayed sample, providing musical and aural feedback which makes tracking orchestral or latency-heavy patches far easier.

It's not ideal, but it’s a useful and workable solution!

Roland Schmidt is a professional programmer, sound designer and producer, who has worked in collaboration with a number of successful production teams over the last 25 years. He can also be found delivering regular and key-note lectures on the use of hardware/software synthesisers and production, at various higher educational institutions throughout the UK

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.