Odd-time songwriting: learn 5 fresh guitar grooves inspired by classic tracks

Master off-kilter rhythms from Soundgarden, The Allman Brothers, Led Zeppelin, Radiohead and System Of A Down

Odd time can have a daunting reputation. But perhaps it shouldn’t.

At its core, it's little more than counting, rarely even requiring you to go beyond the fingers of one hand. We can all tap along in 5s and 7s if we focus properly. But this is only the first step to understanding unfamiliar rhythms.

Get your head around time signatures with this easy guitar lesson

We want to be able to really groove in odd time, and capture the essence of irregular shapes. You can take them to extreme heights, but you have to feel it. Basic counting isn’t the problem. Master percussionists are never really doing this, anyway - rhythmic flow must be intuitive.

How do you train your intuition to do this? Getting to grips with odd time is simpler you might expect. It’s more about exposure than anything else. Bulgarian wedding guests have no problem dancing in 11/8 - it’s easy if you’ve grown up doing it. If you listen to enough irregular grooves then they’ll sink in. As ever, your ears are your most powerful tool.

We can adapt virtually any rhythm to the guitar. Having a few ‘go-to’ odd-time grooves will stabilise your mind and anchor your flow. It’s harder to really get lost when you have a solid base to return to, and it’s easier to start from what you might already know. This lesson breaks down five odd-time classics, with an accompanying groove exercise for each.

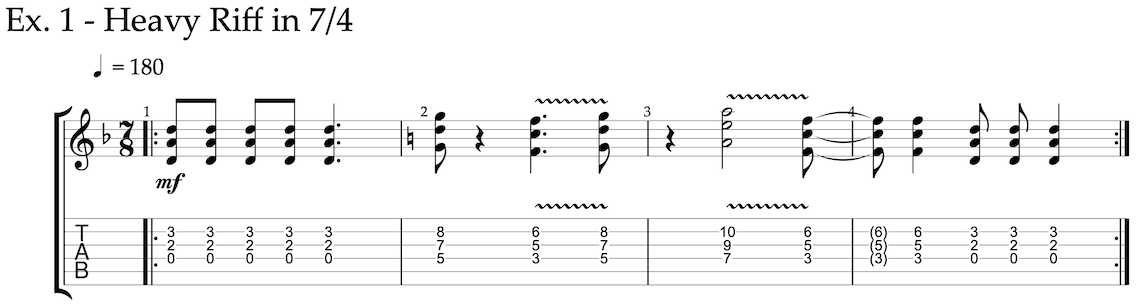

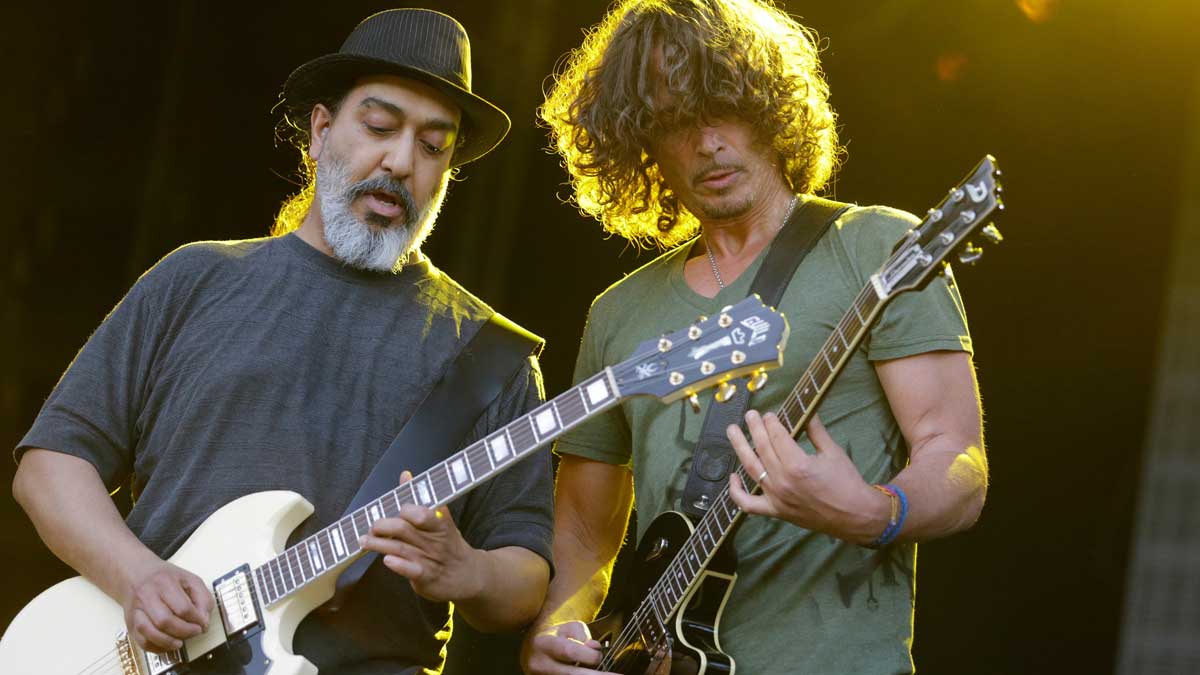

Spoonman - Soundgarden (7/4)

Soundgarden must have had fun recording Spoonman. Songwriter Chris Cornell makes the track’s sentiments clear: “What’s happening musically is the attitude of supporting this guy who stands on a street corner and plays the shit out of some spoons.”

The song is named after Artis the Spoonman, a street performer from Santa Cruz, and also features drummer Matt Cameron playing pots and pans. It helped launch the band in the public eye.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

After a gamelan-like introduction on Artis’s silverware, the band hit a steady 7/4 riff hard (0:15), playing it through four times. The first verse (0:33) then alternates this riff with lines of regular 4/4, calling you to “feel the rhythm with your hands”. The chorus brings a new ordering, playing an emphatic riff in 4/4 before moving back to the 7.

The 7/4 groove is counted slowly, and is about steady power rather than fine detail. Try slowly along to the first minute or two in the following sequence, emphasising the first beat of each grouping. You can use feet, hands, guitar, or anything else. Try unfurling seven fingers in succession to help keep count.

- Introduction: 7-7-7-7

- First verse: 8-7-8-7-7

- First chorus: 8-8-7-7

The 7/4 riff centres the mood of the track, underpinning the intro, verse, and chorus. But is the only part of the piece in odd time, serving as a foil for more familiar patterns. Shifting from 7/8 to 4/4 relieves a tension you didn’t even realise was there. In fact, the band didn’t even spot it at first: guitarist Kim Thayil says that the use of odd meters on Spoonman was “a total accident” - they usually only think about time signatures after writing.

Listen to the following exercise carefully, trying to feel the rhythmic phrasings. Then have a go at playing it. Next, try pulling the groove apart to make your own melodies.

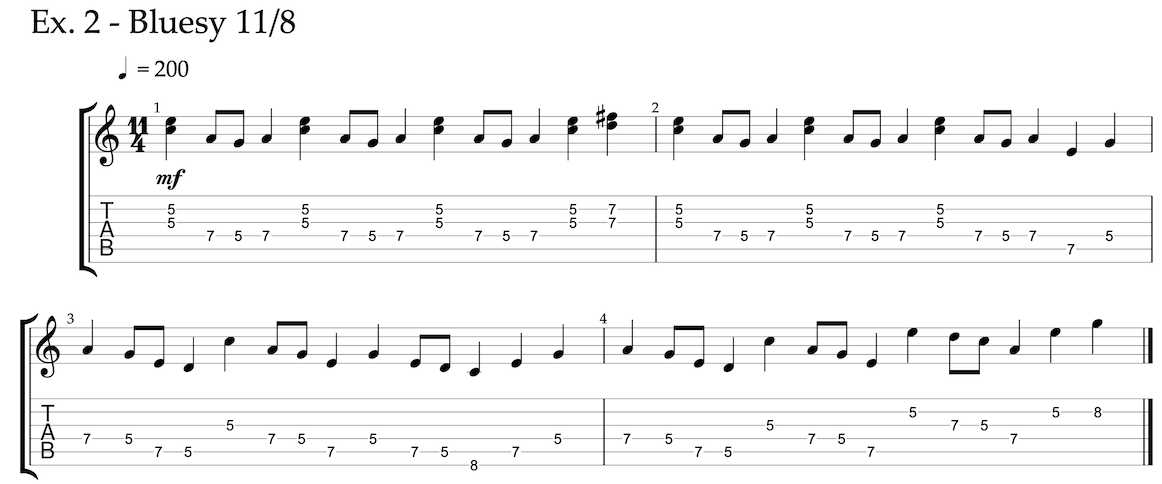

Whipping Post - Allman Brothers (11/8)

The Allman Brothers were no ordinary blues band. They practiced obsessively, and their dual-drum setup gave fresh energy to extended slide guitar solos. Their Fillmore East concerts showcase the band at full power, totally in sync with each other across all manner of grooves.

Whipping Post’s introduction demonstrates their open-minded approach to the blues. They clip the final beat from a familiar 12/8 pattern to make an 11-beat cycle, counted as 3-3-3-2. Follow the bass, and feel the final ‘remainder bar’ jump out at you. They run the 11 over and over, slowly building in intensity, before moving to the more settled 12/8 for the verse and chorus.

The exercise below covers a similar 11-beat pattern.

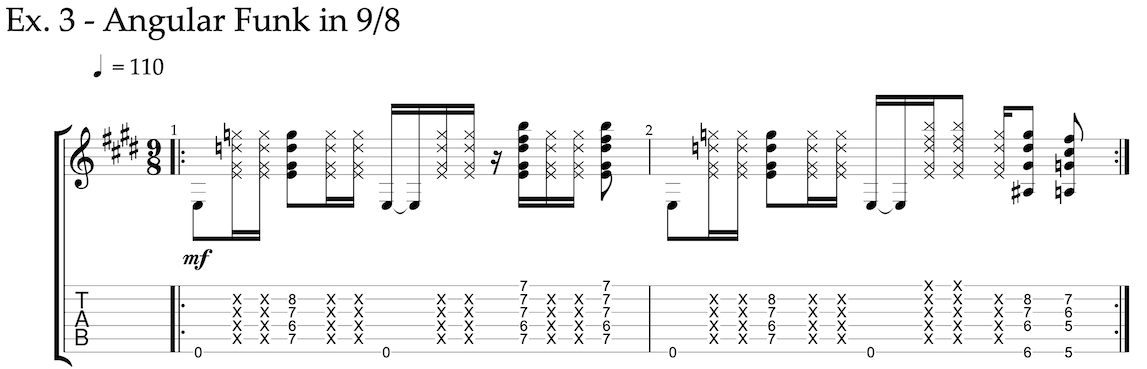

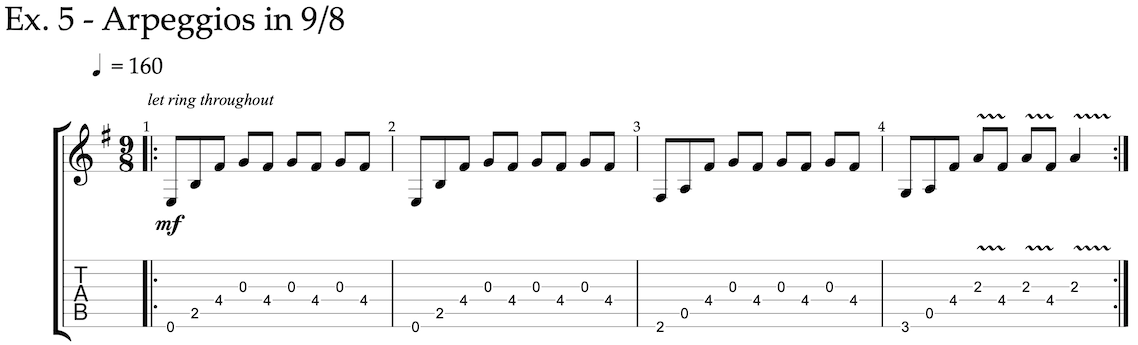

The Crunge - Led Zeppelin (9/8)

The Crunge’s angular funk arose from a studio jam. Bonham started out with the track’s strange groove, before being joined by John Paul Jones’ bass, Jimmy Page’s guitar, and Robert Plant’s controlled screams.

Page traded his Gibson for a Stratocaster for this session, using it to riff off classic funk shapes. He stabs and chicken-scratches his way through familiar 9th chord lines, but has to fit their 8-beat grooves to Bonham’s unexpected 9-beat rhythm. He stretches them out, hanging on for longer to fill the gap.

According to Page, the song was a tongue-in-cheek attempt to capture a certain brand of cultural awkwardness in the face of their African American funk heroes. The stutter is definitely there, but the track still flows. It ends playfully, with the band calling out James Brown-style for a bridge section that never comes (“Where's that confounded bridge?").

Counting the 9 is a start. But funk is never found in even streams of notes - we must try to get hold of Page’s syncopations

It really does feel like a jam. The musicians begin by haphazardly layering melodies on top of each other, seemingly with no consensus except to follow the drums. But the band know where they are, and abruptly come into closer sync (0:23). The track begins mid-bar, and until then it can be hard to know where the first beat of the cycle is (for reference, it’s the highest guitar note/lowest bass note).

Count along with the 9-beat cycle, beginning on this note. Subdivide it as 4+4+1, like two bars of 4/4 with an ‘extra’ beat on the end. This final beat is heavily accentuated by the band, anchoring you to the turnaround, almost as if the starting beat itself has been split. (Incidentally, the 4+4+1 is uncannily similar to a Hindustani-inspired rhythm used by John McLaughlin on Indo-jazz fusion masterwork The Wish).

Counting the 9 is a start. But funk is never found in even streams of notes - we must try to get hold of Page’s syncopations. The following exercise uses a similar 9-beat cycle to do so, counted on the metronome as a slow ‘four-and-a-half’.

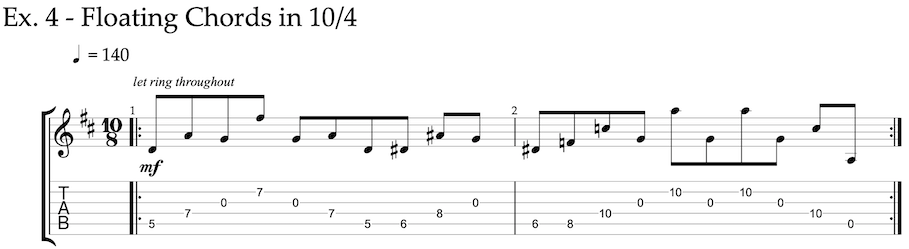

Everything In Its Right Place - Radiohead (10/8)

Radiohead have never been inclined to let their listeners settle. This track certainly has a certain menace, but flows gently over an even 10-beat pattern.

Everything is stretched out, and there is something resigned about how the chords fall, cycling around but never really seeming to resolve back anywhere. It feels as if tension is gradually dissipating, but little has changed by the end of the track.

The rhythm is detailed - let’s take it in stages:

- Count a slow 10 for each chord loop, mirroring the thuds of the kick drum. Notice how our minds pause in suspense at the end of each cycle, having expected it to end after the 8 (on “every-thiiiing” and “riiiight place”).

- To follow the chords, try doubling your speed, counting 20 in the same time period as your original 10.

- Now try subdividing the 20 as 7+4+5+4, hitting the chord changes.

It’s a pleasing one to follow along with - the chords might sound like they’re just drifting around, but change precisely. The cluster chord exercise below uses a similar 7+4+5+4 structure.

Question! - System Of A Down (mixed meter: 9s, 10s, and 12s)

On Question!, System of a Down mix intricate acoustic arpeggios with pounding riffs, running both through several different time signatures. They are most likely drawing on their Armenian musical heritage here, a tradition famous for grooves of 10/8 and beyond. The band speak openly about their roots, and vocalist Serj Tankian has been known to perform Armenian folk songs with his father.

Here, the odd time begins with a melodic focus, as scattered guitar arpeggios create the flow. Heavy riffs then draw you back towards rhythm again, resolving tension by accentuating the underlying patterns. These elements alternate through various grooves. There’s a lot going on.

As ever, the first step to feeling things is to tap along. But this one is harder - you need to count fast while navigating irregular section changes. The key to decoding this complexity is to first isolate the three main rhythmic patterns which occur in the piece. They are as follows:

- 9 subdivided as 3-2-2-2 intro, verse

- 10 subdivided as 3-3-2-2 heavy riffs

- 12 subdivided as 3-3-3-3 pre-chorus & chorus

Tapping out these building blocks first allows us to traverse the intricacies of the piece more easily. This is a prime example of ‘chunking’, a core concept for any improviser. The idea is to group information into definable units, giving us a kind of ‘intuitive shorthand’ to call on.

If you don’t need to think about how to play each chunk, then your mind is free to focus on the broader architecture of what you’re doing. It’s easier to build a house with bricks than sand.

See if you can count along using the 9s, 10s, and 12s, which combine to fill out the entirety of the track’s opening few minutes. It isn’t easy...

- Intro 9-9-9-9-9-9-9-9

- Riffs 10-10-10-10 | 10-10-10-10

- Verse 9-9 | 9-9-9-9 12 | 9-9-9-9 12-12

- Pre-chorus 12-12-12-12

- Chorus 12-12-12 12 12-12-12 12-12

The example study below features a similar arpeggiated 9-beat pattern, as 3-2-2-2. Try substituting in your own chord shapes, or combining it with odd-time riffs.

These exercises will help get you deeper into odd time (for those who want to look further, I’ve got another lesson on Shakti’s odd-time rhythmic turnarounds, full of ideas from North and South India).

Jam along to the tracks listed above and below, and reinterpret the exercises your own way. Try rearranging the subdivisions, or fitting the chords from one into the rhythm of another.

Make the shapes work intuitively - counting along is the scaffolding, and has to come off for the rhythms underneath them to reveal their full glory.

More odd-time songwriting...

- Money - Pink Floyd | reggae-infused 7/4

- Take 5 - Brubeck | fast jazz 5/4

- 15 Step - Radiohead | electronic 5/4

- Wrong Foot Forward - Flook | fast Celtic 7/4

- Tubular Bells - Mike Oldfield | melody-driven 7/4

- I Say A Little Prayer - Dionne Warwick | mixed meter