How to use inverted and opening chords to create smoother pad parts

Make your pads buttery smooth with these useful tricks

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Pads need to smooth. They tie tracks together, bridging the spectral gaps between drums, bass and leads. They should glide from chord to chord almost imperceptibly, but if yours don't we've got a few tricks that will help you out.

In this tutorial were going to use inverted and opening chords to take your pads to whole new planes of smoothness.

For the tutorial we used the Thorn CM plugin and you can download a MIDI file here to help you along the way.

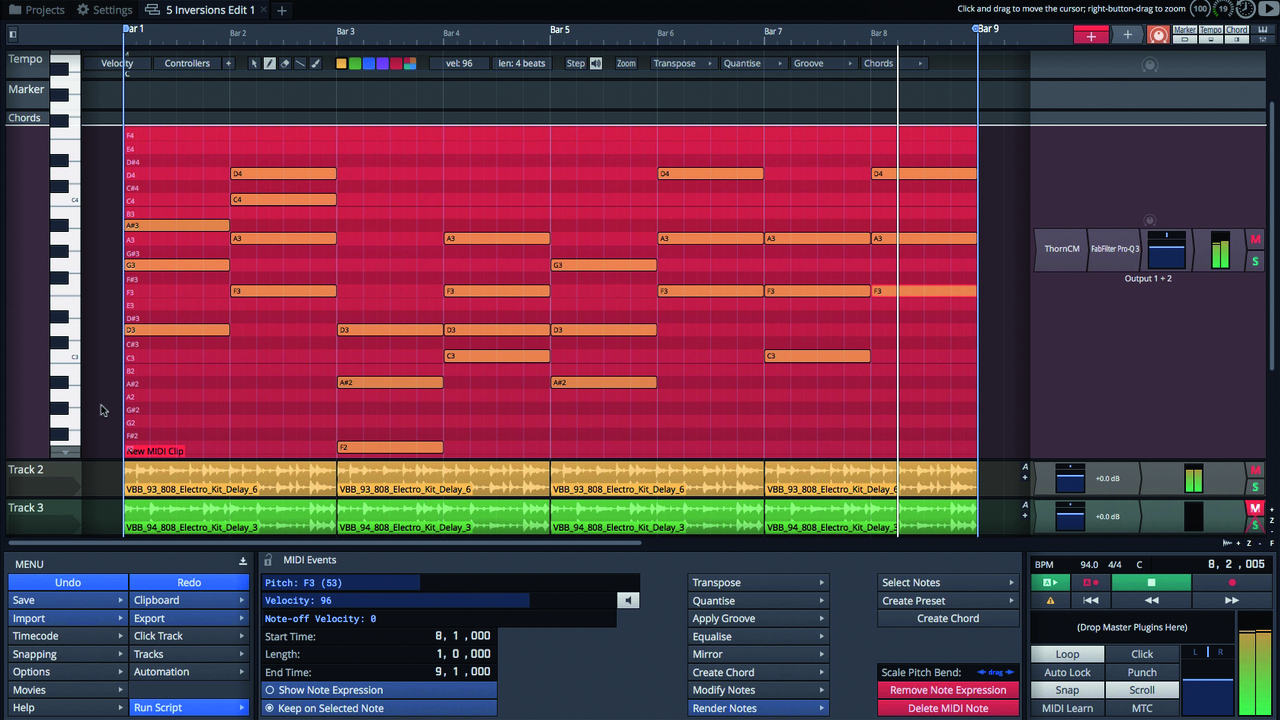

Step 1: Let’s spice up this progression. From the first chord, G minor, take the lowest note – aka the root note – and move it a whole octave up. Now, what was the middle note of the chord is now the lowest note, but that doesn’t really matter. Musically and mathematically, that doesn’t actually change the character of the chord – it’s still a G minor chord.

Step 2: We call this the ‘first inversion’ of G minor – that is, we took the triad in its original position, then moved the bottom note up an octave. We can move the note that’s newly at the bottom an octave up too, making that the highest note. Guess what that’s called? Yep, the ‘second inversion’ of G minor!

Step 3: So what would the ‘third inversion’ be? If we take the remaining note an octave up like the other two, we end up with the same chord we started with. For a third inversion, we’d need a four-note chord. Here’s one in the next chord, D minor 7. Move the bottom three notes an octave up, and you’ll have the third inversion of D minor 7.

Step 4: We can do this to every single chord in order to make the pad part a bit more interesting. For some chords, we shift one note; for others, a couple of notes. The progression now uses the exact same chords, but sounds more interesting, and employs a broader range of notes. There’s another way we can use inversions to help our music sound better, though…

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

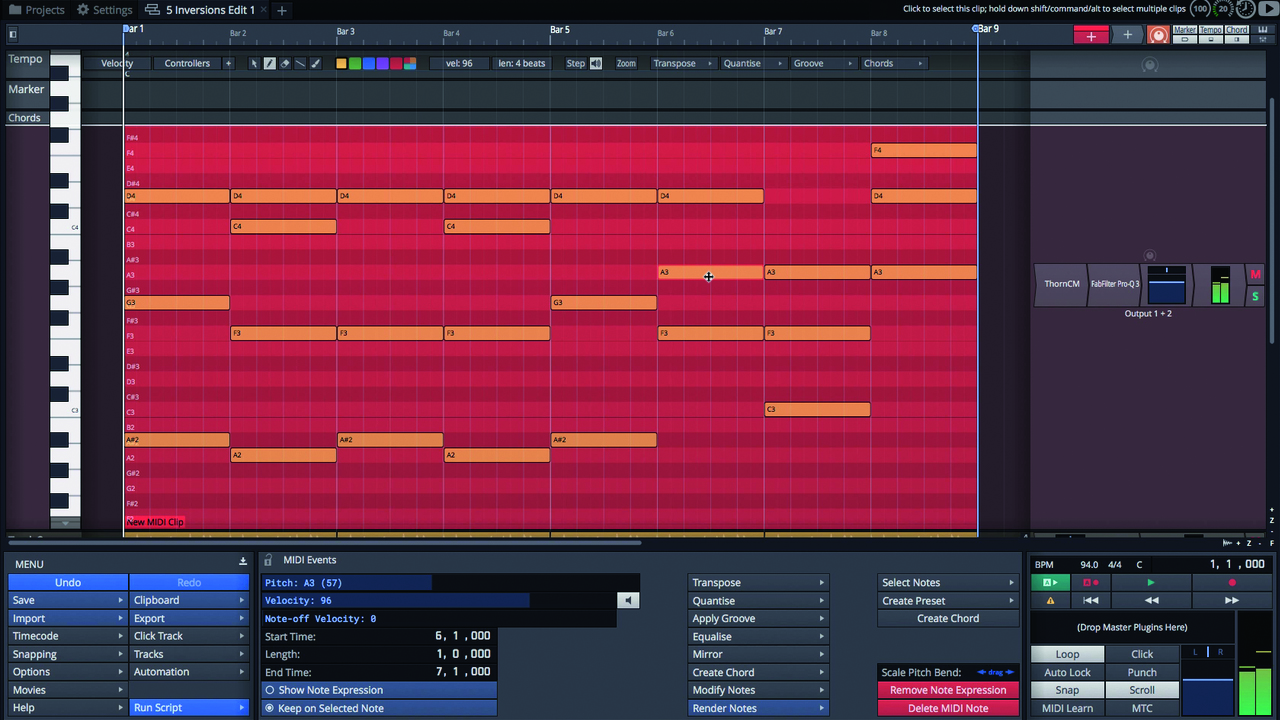

Step 5: The way we’ve arranged things so far sounds nice and broad, and still retains the character of our original chords; but it’s still a little bit jarring and jumpy. Now the mission becomes ‘voice leading’ – we’re going to choose inversions that allow our notes to lead into each other with as few big jumps as possible.

Step 6: By the end, we’ll have the same chords, inverted differently, and the whole passage will use notes in the exact same range, from within the same octave or two octaves. Notes will move more smoothly from one to another.

Step 7: We move notes up and down, lining them up as closely as possible. We even place them into a broader range of notes to let the pad sound cover a wider frequency range. At the end of this process, the chords are still the same, but the notes lead smoothly into each other.

Imagine a group of voices singing this, one person per note. One person can only sing one note at a time, and thanks to these clever inversions, the gaps between notes are now smaller for each person, needing only minor changes between each bar, though we’re using the exact same chords we started off with.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.