How to: select the right scale

An in-depth look at the different ways to find a scale for improvisation

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Every month, Guitar Techniques attempts to answer guitarists' playing posers and technical teasers with expert and practical advice. This time we delve deep into the theory behind selecting scales for improvisation...

The question

Dear GT

I've read various sources of rock and jazz theory and there seems to be two approaches of selecting the right scale to improvise with.

For example over a G7 some say use G Mixolydian as it's the dominant 7th mode of choice; others say use C major as it's G7's I chord.

Likewise, for a G7 altered chord, some say G altered scale (or G Superlocrian) whereas others say Ab melodic minor (ie over a dom7, use melodic minor up a semitone). I appreciate both are 'right' but can you tell me the pros and cons of each approach for practising and improvising?

If it helps I've heard Frank Gambale likes the substitution approach but Mike Stern prefers the 'from the root' approach - maybe one is easier for fretboard and the other for theory?

Pete

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The answer

A lot depends on what type of person you are, how good your ear is and how you process information.

When it comes down to teaching modes we have found that all some pupils need is for us to tell them to play a C major scale over an E minor chord (arriving at the Phrygian mode) and their ear will pick up on the pseudo-flamenco characteristics of that mode without any further input.

Others need to know the maths - play the major scale a major third below the root of the minor chord you're playing over, etc. Both ways are valid, as they arrive at the same destination, but let's take a look at how the different systems work.

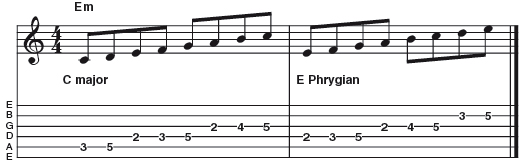

To make sure everyone knows the distinction between the two processes, take a look at the example below: the first scale is C major, with an E minor chord symbol, whilst the second is the E Phrygian scale - the third mode of C major.

Both examples contain essentially the same information, but set out in a way that involves a slightly different learning experience.

The sound achieved should be the same, providing that any tutorial is embellished with information about playing off chord tones.

In other words, it would be possible to play the C scale over E minor and it sound wrong or disjointed because the player is still thinking that the notes C, E and G are the important target notes (example below), whereas he or she should be thinking E, G and B (only one note different, but it makes a big difference to phrasing).

The difference in approach to teaching or learning this one fact would be on the one hand, learning the Phrygian mode in all keys and understanding where it can be used; or thinking that in order to take advantage of the mode's sonic thumbprint you'd need to approach a minor chord by playing the major scale sited a major third beneath its root. To us, the latter route is more complicated, but we were always hopeless at remembering formulae at school.

We're hoping that the logic of applying these different approaches is clear. From here on, the two methods don't really differ too much, even when we look at the area of jazz or fusion harmony.

It's a well known fact that both these styles of music call for an extended form of harmonic and melodic content. Knowing which scale or mode fits where is, of course, very important. As you suggest in your letter, the formula for playing over a dominant seventh chord resolving to a tonic is to play the Superlocrian (example below) which is the seventh mode of the melodic minor scale.

Here, once again, you have the choice to either learn this as a scale in its own right, or as a formula. As long as you observe that the chord tones in G7 (as that's the example you've given) are G, B, D and F and that the mode itself contradicts this by offering the basic triad of G, Bb and Db, then it should be possible to arrive at the type of dissonant sounds that the music calls for.

This is usually where the confusion arises and why this kind of 'related scale' thinking needs to be supplemented with some additional information, otherwise the G Superlocrian and the G7 chord you're trying to play over will remain strangers.

A lot of people seem to think that it's always going to be a perfect fit and virtually haemorrhage with fear when they realise it's not.

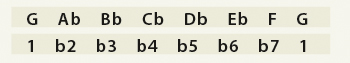

Let's break the scale down. In the last example we have the following notes and intervals. We think this is the easiest way to quantify (and remember) it:

In other words, everything is flat except the tonic. We guarantee that if you were to play this scale in its raw form over an unsuspecting G7 it would sound pretty terrible.

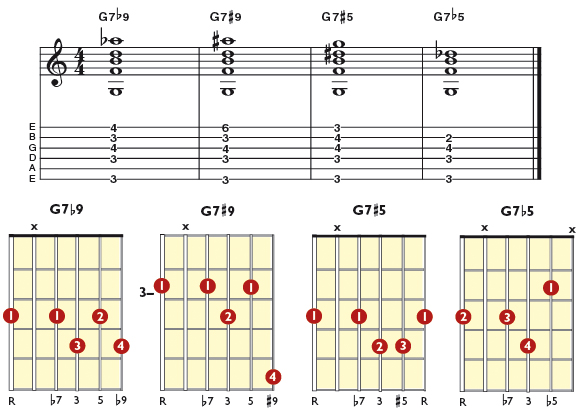

But what it leads us towards is all the altered intervals in a bunch. If we look at altered 7th chords for a moment, we'll see that we can have G7b9, G7#9, G7#5, G7b5 (example below) and that's only for starters.

But the G Superlocrian contains all of those intervals and, to apply a kind of directive from the jazz harmony rule book; if it works in a harmonic context, it will also work melodically, too.

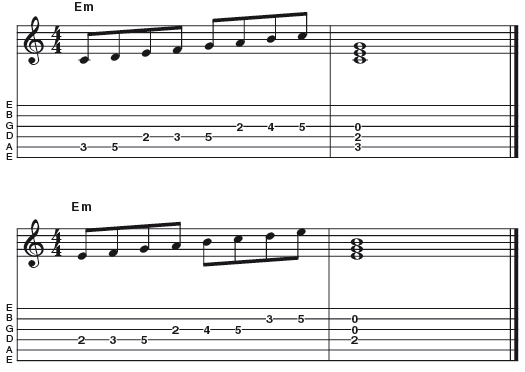

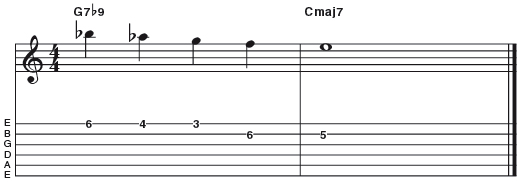

If we were to play over a G7b9-C maj7 chord change, we might play something like the example below. Are we playing a scale, though? We don't think we are, but analysis of what we did might suggest that we're quoting from G Superlocrian.

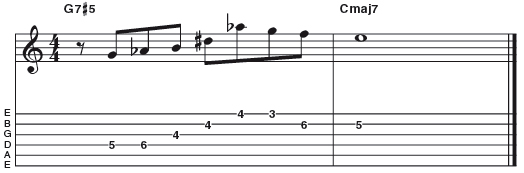

Similarly, if we were to play over G7#5-Cmaj7, we might play the phrase in the example below. Once again, when all the jazz Sherlocks come along with their magnifying glasses, they may conclude that again, we're quoting from G Superlocrian. But actually we're not thinking that way at all...

This brings us to the most important lesson anyone can learn about related scale theory: scales are to music what the alphabet is to literature. They are undeniably an important structural part of music, but it doesn't end there and if your goal is to learn all your scales and modes so that you can shred like some kind of jazz ninja, you've missed the point.

We once went to a masterclass with the late, great Joe Pass and he said we shouldn't ask him anything about modes because he didn't know anything about them. Joe had what he called an 'altered' scale (example below) similar to the Superlocrian.

The important thing was that he knew what sounds it gave him and had the taste and discretion to use it magically every time.

We have had the privilege to interview many of the world's top jazz and fusion players, including Scofield, Metheny, Robben Ford, Martin Taylor, Larry Carlton and many more. And not one of them has ever told us that they apply any theoretical knowledge when they are playing. They left it behind them years ago, rightly regarding it as a means to an end and not the end itself.

We'll leave the last words to jazz legend Charlie Parker. When asked what advice he would give jazz students he said: "Learn your scales - then forget all that shit and just play!"