“I have a great deal of respect for Ed Sheeran. He fought his corner and stood up not only for himself but the whole music industry”: A quick-fire guide to copyrighting your music

Before releasing anything, make sure your legal rights are secured

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Releasing your music into the ears of millions is now an achievable aim for every self-releasing artist, but securing your rights as the legal creator of said music is a vital step. In today's world of rapid uploading to streaming and social platforms, and immediate listener response, getting those official copyright ducks in a row is all too often overlooked. Sometimes, it's not until a fight over ownership/usage erupts, that artists even think of it.

Legally speaking, it's the only way to make sure that people don’t start using your music without your permission, and - worse than that - claiming that they themselves created it.

The thought of someone passing off your work as their own might be rage-inducing, but this quick-fire guide will take you through all the essentials, in a simple, waffle-free manner. We intend to arm you with the knowledge you need to protect your rights as a music creator.

The essentials of music copyright

So, just what parts of a track or song does the law regard as ‘copyright’ anyway? In the US and UK at least, it splits into two copyrights: the ‘Sound Recording’, which protects the specific recording of a song, and the ‘Music Composition’ copyright, which protects the actual song itself, regardless of the performer or recording artist.

These two copyrights can actually be held by different parties, but - assuming you’re a self-releasing artist - both of which will need to be claimed by yourself. Composition is typically displayed as ©, and recording copyright is represented by ℗. Asserting these symbols on your releases, websites and other places your music is heard is a must.

The law on securing your rights as the music copyright holder differs country-to-country, but under UK law, you might be surprised to learn there's actually no formal ‘official’ administrative’ way to copyright your music. However, you can create a date-stamped record of the track to formally register that the track was created by yourself at a certain date.

The most frequently recommend way of confirming your copyright, is by burning a copy of your track to CD (or placing it on an inexpensive USB stick) and mailing it to yourself within a sealed package. You shouldn’t open the package, as this will remain hard evidence of named and time-stamped proof of its creation date - and its creator.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Alternatively, you could just email a WAV or MP3 to yourself, or save the project files to cloud storage, with dated metadata. Though this later approach can be manipulated, it’s not likely that anyone would really challenge it. It's best to do this at any rate.

In the US (and much of the rest of the world) it’s highly recommended that you register the copyright with the US Copyright Office (or government copyright office of your country). This is the ONLY officially recognised way of securing your copyright.

Though, you’re still technically granted the automatic copyright rights of any music you make (even if you don’t register) if you want to take any copyright violators to task, then - following new legislation introduced in 2019 - you’re going to need to officially register yourself as the copyright holder with the US Copyright Office. You’ll need to submit an online application, plus a small filing fee to register. But it’s 100% worth it to keep your rights secured.

Your copyright for the work will last until 70 years after your death (a cheery thought!), after which it is passed into the public domain.

This is all well and good for solo artists, but what about bands - or albums/tracks that have multiple writers, producer credits and other performing rights splits?

Perhaps arguments about percentages might flare up, or perhaps another party might want to claim a share of the writing credit. The best way to negate any of these hypotheticals, is by securing a written-down, split agreement that you agree between the stakeholders, and locking this in via a formal third-party.

In the UK, the UK Copyright Service not only provide tamper-proof evidence of your copyright, but also make sure that your work is protected internationally. You can upload a full album’s worth of tracks, and pay £85 to solidify yourself as the legal copyright holder for 10 years, while £51 protects it for five years. The good thing is, as you write more and more work, the copyrighting fees reduce. We've used it in the past, and while we've not claimed any infringement to date, we certainly sleep more comfortably at night.

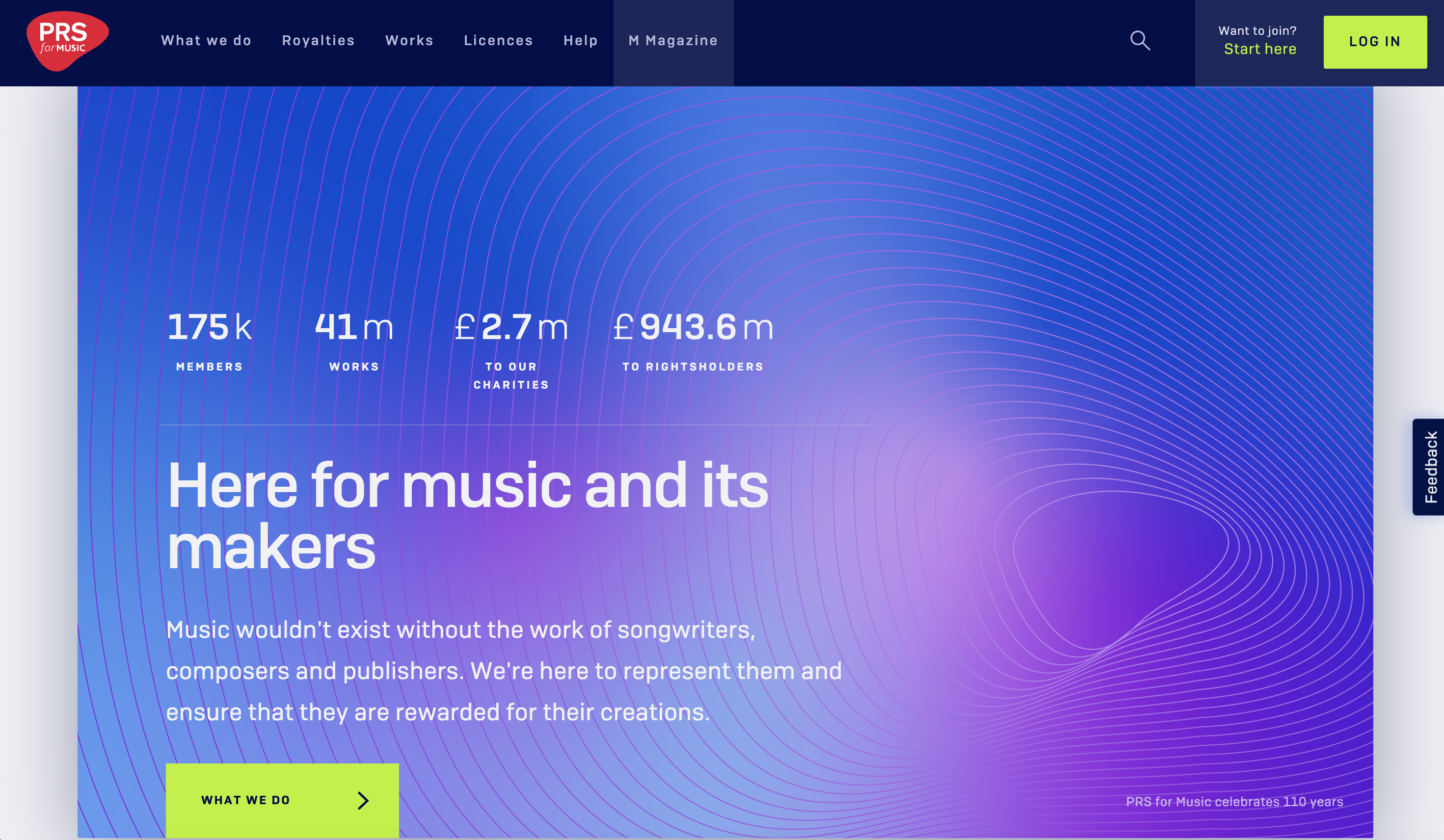

If you’re UK-based, then registering with the PRS should be on your to-do list anyway. When you’re signed up with PRS, any songs you register will be placed under copyright protection (the ‘Music Composition’ half of the copyright), and they’ll make sure that any unlicensed playing, performance or usage of your song is spotted and brought to your attention.

There’s numerous other PRS member benefits too, so make sure you sign-up. In the US services like BMI.com and ASCAP provide similar services.

There’s also the PPL, which handle music licensing and payment security for the specific 'Sound Recording' copyright. This is vital if you want your music to be broadcast on radio, TV and and the web - and get your tracks heard!

Once you’ve got your copyright secured, then you’re all set. But, what if you actually notice your track has been used by someone without your permission, then it’s not always the case that you can make a viable copyright claim.

If a track has been used in a 'fair-use' context then it's not worth pursuing. Though the term 'fair-use' is pretty subjective and no fixed standards exist on where the definitions lay, it’s generally agreed that a review or critique of a track can be counted as fair-use. Using the track in an academic or instructional context can typically be considered fair-use too. But, there are limits. It may still be worth pursuing if you feel too much of your track has been played, particularly if you’re not credited or cited as the copyright holder.

Because there’s some ambiguity as to what counts as part of the composition, there can still a lot of legal wrangling about the ownerships of songs, particularly if your track does very, very well…

Often people might make a copyright claim for a song from a successful artist, just in the hope of a settlement fee. In a recent article for Audio Media International, this author spoke to a pair of forensic musicologists (legal experts who specialise in music law), and unpicked some of the complexities of a few of the high profile court cases.

Forensice musicologist Peter Oxendale told this author that he admired Ed Sheeran’s long battle in court to try and quash this trend, “I have a great deal of respect for Ed Sheeran," Peter said. "He fought his corner and stood up not only for himself but the whole music industry.” Further battles continue to rage, and the results of which can determine the shape of legislation around music copyright law.

Copyrighting your music - the checklist

So, let us boil down exactly what you need to do to get your rights protected, in seven simple steps:

- Write and record a new piece of music, or amass an album’s worth of tracks.

- Save all your files, projects and early demo versions with dated metadata.

- If you’re in the US, register this work with the US Copyright Office

- If you’re in the UK, register this work either by manually creating a time-stamped log (via posting it to yourself) or by using a third party, like the UK Copyright Service to formally log yourself as the copyright holder

- If you’re UK-based, sign-up to both the PRS and the PPL, in the US, we recommend the BMI or ASCAP to keep on track of your twin copyrights.

- Keep a log of every further agreement, or license you provide for music to be heard elsewhere, to keep on-top of just what you’ve agreed, and when.

- Rest easy, and get back to making music. Rinse and repeat!

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.