“Ultimately, I believe it will be the end of mankind”: We catch up with synthpop legend Gary Numan to talk sampling, running a record label and the future of music

Following the reissue of his 1984 album Berserker, Gary Numan reminisces on the demise of Numa Records and the dangers of AI

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One of the first icons of synthpop, Gary Numan’s phenomenal early successes in the late 1970s and early ‘80s made him a household name. Chart-topping albums such as Replicas, The Pleasure Principle and Telekon were critically hailed, and Numan became a poster boy for an electronic instrument-dominated future vision of pop.

But then, Numan suddenly found himself at a crossroads.

Dumped by label Beggars Banquet following the. 1983 studio album Warriors, and despite discussions with Richard Branson’s Virgin label, the synthpop icon decided to seize control of his career, start his own label - Numa Records - and produce for other artists.

The venture was a disaster, virtually bankrupting Numan by the end of the decade.

However, despite its commercial failure, the label’s recently reissued debut Berserker contains some of Gary’s most left-field work, with contributions from renowned session singer Tessa Niles, producer William Orbit and, bizarrely, ‘80s horror icon Caroline Munro.

The album also saw Numan step into the digital domain for the first time, employing Wolfgang Palm’s incredible PPG Wave synthesiser.

On the heels of its reissue, we caught up with Gary to discuss his memories of that time, and his views on what the future is looking like now for popular music…

MusicRadar: Some of your mid-‘80s music is unfairly glossed over. Having left Beggars Banquet in 1983, did you instinctively feel that setting up your own label would be the right career move?

Gary Numan: “We did make a fairly half-hearted attempt to see what other interest was out there - my dad had a meeting with Richard Branson on a canal boat in London somewhere, but I don't know how good a deal it would have been in terms of financial support and what they were committing to.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"I was leaning towards wanting to go my own way anyway because there was a misguided sense of glamour in having your own record label. Bear in mind that Beggars Banquet was tiny when I started and only took me on because I’d already made a record and had my own van and PA system. I'd seen them grow from a tiny little thing into this big record company and had an idea of doing that myself with the freedom to record what I wanted and not have to worry about A&R intrusion and all the compromises you’re expected to make.

"It was very naïve as I clearly didn't realise how much furious under the water paddling had been going on and how lucky Beggars had been to have someone like me come along and explode. The decision was part stupidity, part ambition and part about being unhappy with what conventional record companies were offering.”

MR: What difficulties did you encounter straight off the bat?

GN: “I learned fairly quickly just how difficult it is in relation to the horrendous deals that record store chains forced labels to accept and all the tricks that made it very difficult to succeed.

"I also learned how shitty some bands can be, because we did sign some. I don't want to put people down, but some of their expectations were certainly surprising. A couple of them were really lovely and undemanding, but some acted as if they were already treading the boards at Wembley Stadium and I was lucky to have them.

"Whether you're successful or not, I don’t think there's any place for arrogance and I don't like star-tripping if you're a star, let alone if you’re not one.”

MR: Is it true that you tried to sign Depeche Mode to Numa Records?

GN: “Well, almost. I went to a nightclub in the West End – it might have been Heaven, and they were there. There was no stage - they were just in the middle of the dance floor setting up their gear and started doing their thing. I thought they were amazing, absolutely loved it and wanted to tell Beggars Banquet to sign them.

"It was a very long time ago, so forgive me if this isn't quite the way others see it, but my memory is that I spoke to Rusty Egan that night and told him that I was going to see if I could get them signed to Beggars, but Rusty said ‘I’ve already got them something’, which I think was an absolute fucking lie. He was just fending me off, but that stopped me from pursuing it.”

MR: The first LP you released on Numa was the highly underrated Berserker, an album that felt quite similar to Tubeway Army’s Replicas in terms of having a very strong visual image tied to a concept…

GN: “It didn't have as rigid a theme as Replicas, which was specifically about what London might be like in the next 50 years based on a newspaper article about a gang that was roaming around, getting off at tube stations and beating people up. What a lovely world! But that was where the name Tubeway Army came from and all the songs were relevant to what this technological future might be where the computers would see people as an obstacle to the smooth running of society and start getting rid of them in ways they wouldn't become aware of.

"Berserker was slightly more fragmented. My Dying Machine, for example, was about how it feels to be in an aeroplane where you know something’s wrong and can feel it talking to you, but you don’t know what and there's nothing you can do about it. The themes themselves were more musical because we started using the PPG Wave system, which was one of the first computer-based samplers.”

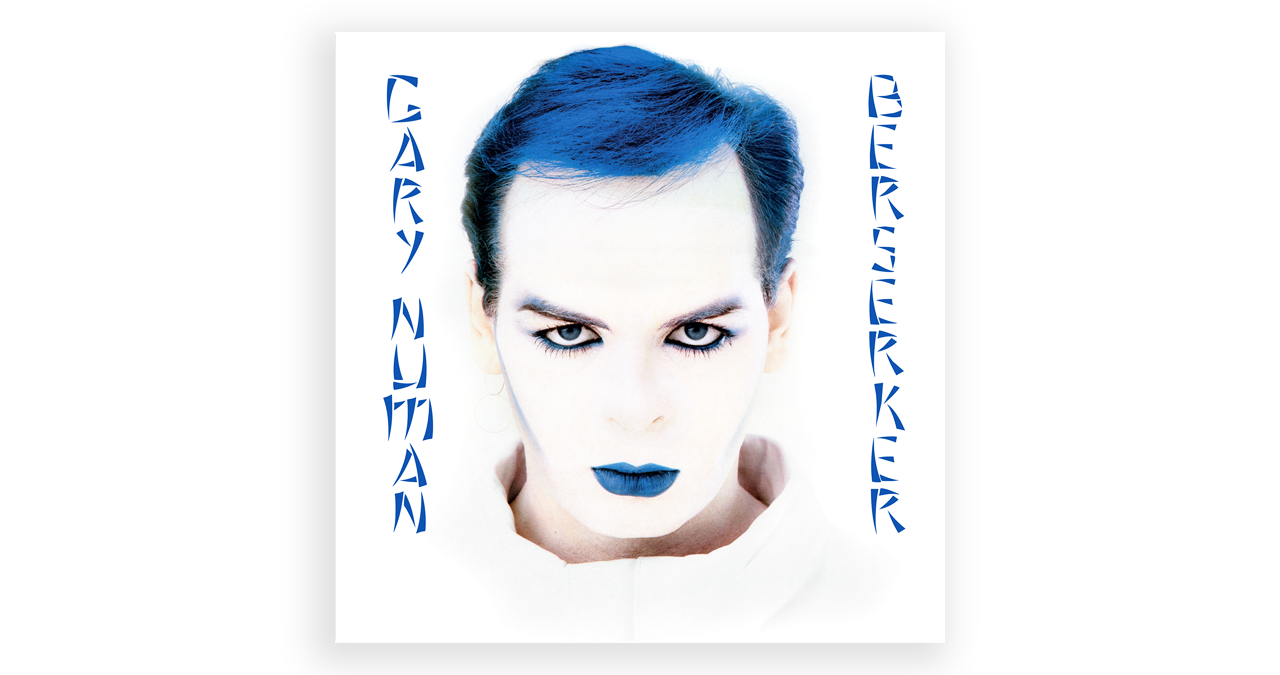

MR: What about the imagery itself? Even now, the artwork really stands out on a shelf…

GN: “I agree that a really strong album cover attracts people to check it out. It doesn't mean they're going to like the music, but they might gravitate to it when they’re leafing through albums in a record store – if that still happens. When it first came out, the artwork was actually used as a cover shot for a magazine in Germany and won cover of the year at some magazine awards ceremony. So it was a very powerful look that did grab a lot of attention, and still does. I went to a makeup specialist who I’d previously worked with and explained what I wanted with the blue eyes and lips, but the hair I did myself with help from my mum.”

MR: You also had the foresight to enlist Tessa Niles, who went on to become one of the all-time great session vocalists. She'd previously work with The Police and Tina Turner - is that how you spotted her?

GN: “It was a friend of a friend I think. I was also using a fantastic backing singer called Tracey Ackerman, but Tessa could do whatever type of vocal you wanted. I’d ask her to adlib over a part and she'd do all these amazing things off the top of her head as the music was playing.

"She was a phenomenal singer with amazing control and had an ability to express all different emotions on instruction. It’s no wonder that she became one of the biggest backing singers around.”

MR: Musically, you seemed to be subtly influenced by Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s Two Tribes bass sound. As this was your first LP on a new label, did you feel the pressure to keep up with trends?

GN: “When Relax came out, it set an entirely new standard for production. It just took everything to a completely new level, which is one of the reasons that we started to work with the PPG Wave system, because it allowed us to do the sort of fantastic sequencing that Trevor Horn created with Frankie where you could create and build your own sounds and mix them into something conventional. It was impossible not to be influenced or affected by that in some way, so we needed to figure out how it was done and try to follow in their footsteps.

"There was one sound that we used called ‘chair leg’, which was actually the sound of somebody scraping something across a chair leg that had a sort of harmonic feel to it. We were finding sounds that became part of a musical vocabulary, although, to be fair, we’d already been going that way for some time.”

MR: Within the analogue domain?

GN: “Before the PPG Wave, we were creating samples the old-school way using tape. We’d go around with a five-inch reel-to-reel tape recorder and put microphones up against all sorts of things and record noises. Sometimes that would be a door slam or a sledgehammer onto a brick, but in their raw form those sounds are not necessarily that exciting - it’s only when you bring them into the computer and start working with them that they become something different.

"Pre-computer, we’d record those sounds onto tape, varispeed it and put weird effects on until they became very, very different and could work at the tempo of a song. Because you’re changing pitch, that mostly worked with rhythmic things, but it was very crude and really time-consuming. When sampling became a big thing, it was amazingly easy to do things that were taking weeks and the PPG Wave allowed us to do that, as difficult as it was to operate. "

MR: So difficult that you had to enlist two guys who called themselves The Waveteam to help operate it?

GN: “It was basically a computer with a five-inch floppy disc and a keyboard called a Waveterm 2.2 or 2.3. It was a big, massive blue thing, and the keyboard part wasn’t a problem - you’d load the sounds into the computer and the keyboard would, supposedly, play those, but it was brain-numbingly frustrating at times.

"Mike Smith from the Waveteam was very clever and able to coax stuff out of it more than anybody else because he had the patience and knowledge, but I still have endless visions of him standing there shouting ‘What are you doing?!’

"When it worked, the PPG Wave had some of the most amazing sounds, so it was well worth Mike’s pain - although he might not think so! The PPG dominated my songs for a while, until the Roland D50 came out.”

MR: Another legend-in-the-making you worked with was William Orbit who remixed the track you mentioned earlier, My Dying Machine…

GN: “I was loosely involved with Miles Copeland by that point and I think he was managing William at the time. We went to hang out with him for a bit to listen to some of the music he was making and he was super-clever and creative in a very different way to me. He did the My Dying Machine remix, which I thought was fantastic for its time."

MR: Rather unusually, the song Pump It Up was remodelled for horror film actress Caroline Munro as Pump Me Up. How did that come about?

GN: “I think Caroline got in touch with some of the people involved with the studio that I co-owned and said that she wanted to record a song or embark on a pop music career. I was already in the studio working on all the Berserker stuff, so I told her we could do a track together and see what she thought of it. She's very beautiful, but also really lovely, down to earth and an easy person to work with, so I diverted Pump It Up towards her just to see what would happen.”

MR: Despite being a bit off a long lost classic, why do you think Berserker wasn’t a commercial success?

GN: “We had a label manager, but he was unfamiliar with the radio problem I had. Normally, if you've got a record in the lower reaches of the chart, radio would start to playlist it and then you’d print up another 100,000 singles to make sure the stock was there for when people start buying it.

"Of course, I didn't get any radio play no matter where it was in the chart so we ended up with 100,000 Berserkers stuck in boxes in a fucking warehouse somewhere.”

MR: It sounds like this was this the first of many painful lessons to come?

GN: “It was frustrating when we started to realise that the record stores, especially the big chains, were utterly ruthless. It got so mad at one point that they would buy one copy for every 20 you supplied them with and anything that didn't sell was scratched, sent back as damaged and you lost your money on those as well.

"I learned very quickly that it was almost impossible for an independent label to actually break through because you were fighting against such ridiculous expectations, costs and bullying. I'm not blaming them for the demise of Numa Records, because I'm sure I contributed to that myself though my stupidity and ridiculous optimism, but they were awful and every time one of them went under I would rub my hands with joy”

MR: And today, with the resurgence of vinyl, are things more equitable?

GN: “I’m with BMG now and they deal with that side of things, but it's very different to when I was trying to get Numa going. I'm sure that there are still deals to be done and if people have leverage they’ll use it to their benefit, but I don't believe it's anything like it was. So much of music is downloaded and streamed now, which brings another set of problems, but I think that's a slowly improving situation.”

MR: Your team used some clever AI imagery for the Berserker visual campaign and we now hear of an AI-created band called Velvet Sundown that has 470,000 monthly Spotify listeners. How do you feel about where all this AI stuff is going?

GN: “I’m too old to fear it because by the time it's done the damage it will do I'll probably be retired, but there's so many different ways of looking at AI. Ultimately, I believe it will be the end of mankind, but from an artistic point of view it will do amazing things. It will create amazing images and music and there will be avatar pop stars that look every bit like the real thing. You'll probably go to gigs to watch them, just like you do with the Abba Voyage show, which looks unbelievable and that's only going to get better.

“There will be a vast amount of AI bands that will all look beautiful and I'm sure they’ll have amazing artwork that probably moves and you'll go to a gig and it’ll look as if they're actually there, so we’re as replaceable as a fucking cotton bud.

"My wife, Gemma, has long had this fear of robot armies marching down the streets and zapping people, but I don't believe that's going to happen and I think AI will do a lot of good as well. It's going to make amazing advances in technology, healthcare and diagnostics and so on, but it’s a pivotal moment in our history as far as the hierarchy of people making the decisions, and who's ruining the planet."

MR: Can you foresee AI creating new versions of old material, and might that be a good thing for certain artists commercially?

GN: “For most of the big acts, especially the legacy ones like Bob Dylan or Queen, the publishing has been sold on so we’re not earning from that. When you get into your 60s, 70s and older, there's just a big chunk of money that can be used to create a different kind of legacy to pass on to your children. I don't doubt that what you’re saying is going to happen, but I very much doubt whether it will be good for us.

"If you're a 17-year-old girl, who would you rather come and see, some 75-year-old bloke doddering around the stage with grey hair, which is what I'm going to be soon, or a young version of me that looks absolutely like he’s there, all young and pretty?

"Once you've got used to the fact that you're looking at virtual people that will be the future. If we survive long enough, at some point it might go full circle and people will want to listen to somebody that suffered the way they suffered, rather than somebody doing an interpretation of somebody that suffered. How pessimistic is that? [Laughs]"

MR: Berserker is the first album you’ve re-released from your Numa back catalogue. What’s the timeline for future releases?

GN: “BMG are just in the process of putting that together and then we hope to bring out everything from Machine & Soul onwards right up to where I am now. If we can get that deal together, they've got a plan in place that would take the back catalogue stuff up to 2030 or maybe longer, and that will incorporate as many unreleased tracks, remixes or alternate versions that have never seen the light of day before as possible.

"So from a Gary Numan fan point of view it's going to be a very interesting next five years because there's so much stuff coming out.”

The reissue of Gary Numan’s Berserker is out now on BMG.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.