Classic album - Underworld’s Rick Smith on Second Toughest in the Infants: "No plugins, no compressors, no gates… I don’t know how I did it!”

Back in 2010, Underworld’s production mainstay talked us through the band's seminal mid-’90s long player

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

School days…best days of your life. Unless you spent it being held upside down in a toilet, having your Panini sticker collection surgically removed from your pockets.

If Underworld had been at your school, they’d have had your back. They want everyone to get along. Especially when it comes to all their musical heroes. Normally, in an album that featured such a wide range of influences, one style would come out victorious. Not on Second Toughest…

Everyone was BFFs in their world. They made electro, dance, reggae, DnB, rock, gospel and jazz shake hands and make up.

“The album features a lot of normally competing musical influences, because we all had a love for all types of music,” says main production talent, Rick Smith. “I had a strong feeling that we could bring something new to club music. We just followed our noses, and still it made this feeling inside of you that made you want to dance.”

Journey to the Underworld

Released in 1996, Second Toughest… delivers the same jaw-dropping standard of their debut, Dubnobasswithmyheadman, but ramps up the subtly and variety, proving once again that Underworld were one of leading lights of the mid-’90s Dance music fraternity.

At the time, they described their album as a “roller coaster… a ride from start to finish”, which sums up the journey perfectly. From the peaks of higher BPMs, to the mellower dips that let you catch your breath, this album never rests at one genre or tempo for too long.

The trio of Darren Emerson, Karl Hyde and Rick Smith pooled their talents and simply astonished here. Hyde supplied raw guitar licks and lyrics twice as catchy as your indie-pop darlings, and twice as rambling as any drug-addled beat poet. DJ Emerson brought the energy and knowledge of the modern club vibes to the studio. And Rick Smith handled the engineering, production and keyboards.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Second Toughest... manages to hit a near perfect balance of tight, sonic backdrops and some of Hyde’s career best vocal performances.

A Melody Maker live review from March ’96 declared the singer “way better than Damon Albarn, and on par with Jarvis at the very least”. Dazed and Confused compared his style to a “word clash between Ginsberg and Mark E. Smith”.

House music

It was the last album the band did in Smith and his wife’s spare bedroom in Romford, and he squeezed as much equipment into that tiny room as he could.

“It was probably about twelve foot by about fourteen,” he says. “And noise was an issue. My missus’ patience was deeper than the deepest ocean. The racket that would come out… Repetitive beats for months on end.”

Besides the cramped conditions, times were also tight. Smith had to sell a lot of gear, including some prized keyboards, to pay off the band’s existing debts. The claustrophobia of their working space, and the moths in their wallets, seemed to have fuelled their desire to create such vast worlds of rich music.

The formula proved a hit. Second Toughest… made most end-of-year lists, and was nominated for the Mercury prize.

It remains a high point of the career of an always-breathtaking outfit. And as a side note, boasts the greatest title in dance music history since David Holmes’ This Film’s Crap (Let’s Slash The Seats). So there.

Track by track with Underworld’s Rick Smith

“The first three tracks run together like a triptych. Funnily enough I was looking through old DATs the other day to find the original material so we could play these out live, because over the years it has just morphed into versions of a version of a version. When I discovered the originals it just surprised me that these tracks were made up of a real assemblage, a real labour of love.

“The whole thing came together from at least three different pieces of music, from across a period of nearly a year. I think it came together in the form you recognise on the album in the last two months of that period. It came together from these various pieces that seemed to have something about them, either a mood or a feeling, or with vocals with a certain lilt to them, and they needed to form into something to make them all more substantial.

“At that time in dance music, dancing was different. I was really having such a great time going out to clubs and really enjoying the feeling of the rhythm, grooving about with my pathetic little dance in a corner with my eyes closed. I really enjoyed the - and I hate the term - trance. I wanted to make music like that, stuff that had small changes, but felt much larger if you had the patience.

“The entire album was all about not going for it, and not hitting the pleasure zones every 16 bars. What else surprised me when I was listening back to it was that it was nearly 17 minutes long. But it seemed so natural.”

Banstyle/Sappy’s Curry

“This was two pieces of music that could have existed on their own, but I was caught up with the idea of fusing things together into more epic journeys. It was kind of challenging.

“Barnstyle was totally influenced by what I was hearing in drum ‘n’ bass at the time. Trippy people like LTJ Bukem and stuff like Goldie’s Timeless. I was really loving the beats and the playful way they sounded and the busyness of them. Barnstyle was a much more mellow Underworldy take on it, rather than so fierce. It’s a piece that I still enjoy to this day, actually.

“Sappy’s Curry was a straight up, very heavily dub-influenced rhythm and feeling. And it sat really nicely with the drum ’n’ bass, as it does today, what with dub and reggae styles still flying around in jungle and dubstep.”

Confusion the Waitress

“This was a very simple piece, based around a very simple chord and loop, and a slightly modulating Nord bass. It all hangs on what you get in the track in the first 30 seconds, really. It’s also one of the first pieces on the album that has that gentler approach to Karl’s vocals in it.

“It’s kinda feeling dark by this point. It’s not an uplifting sound - it’s more mellow with a driving rhythm, and subtler. It holds a really strange balance between feelings and emotions.

“Over the years it’s one I think of, not with a great sense of dissatisfaction, but one I think would have been nicer to have developed more. At the time of making a track, any track, it feels good when you’re doing it, but a week after mastering it feels rubbish. Including this album. We never sit around thinking we’re going to make a track that will last forever. That sounds a bit lofty to me. We just followed our hearts. It’s a very simple process. It’s a case of, ‘does this turn me on? Yes it does. Thank you very much’. You know?”

Rowla

“This was a very deliberate track. It came on very late in the album. It might have even been the last one we did. I say this a lot in interviews, but albums take me a long time to do. I don’t work really quickly.

“So they cross quite large time periods. Albums, up to the last one we’ve just done, end up being about 80% there. Eight out of ten tracks are in place and we’ve got two weeks to the deadline when we’ve got to master, or I’m a dead man. There’s always a scrabble around at the end to get it down.

“I remember there was some very good hard house music going around at the time. Acid House was becoming less popular and sounding a little dated to a lot of people, but I still loved the feeling of it. So Rowla had an acid track type of feel to it, with a Roland 303 roaring at you, distorting a bit, but done on this Nord synthesizer, which I absolutely adored, and didn’t have for the first album. I was trying to focus and take my time and do a slowly building, aggressive piece in that style.

“We played this track so much live over the years. And when I listen to the album version I personally find it a bit disappointing. When we play it live it’s so much rawer and louder, and hammers along, really.”

Pearl’s Girl

“This is also really good to play out live. It’s just simple, chopped up drum loop vibes. I say ‘chopped up’, but in a playable way, as one would re-trigger a sample, you know?

“I know this track came together quite quickly, over the period of about a month. Karl, Darren and I were jamming on an idea, which never really seemed to go anywhere, but there was something there. So I revisited it again about a month later, and a chap that works with us, Mike Nielson, an engineer, did a quick mix while I was halfway through the tune.

“That really helped in the track’s development because he really nailed the sound of it, as it wasn’t a house or obvious techno piece at the time, it was much rowdier. I loved the way it almost crossed over between a house and techno, and a drum ’n’ bass feel. The absence of a four-to-the-floor was unusual for us.”

Air Towel

“It’s techno, with an electronic pulse. It’s got a really interesting vocal journey from Karl. We were very much into not doing the same thing again. We wanted to do one style and move on. I would take whatever lyric or vocal had been put down and edit it together. Bear in mind, this was at a time when it wasn’t hard drive-based, so you had to make choices before you put stuff back on tape again. The vocals had a really interesting flow, they didn’t need a lot of editorial, or prettying up.

“We also used a vocoder in a quite a strong way, which we’ve always done. It’s a crucial piece of kit for us, the Roland Vocoder VP-330. We have three of them in the studio now. It’s the greatest vocoder in the world, for the way I use it, anyway, which is for vocal support. It’s just an astonishing piece of equipment.”

Blueski

“They were really exciting and busy times when we made this album. Which seemed to carry on for another 15 years, to be honest. So we needed some mellower tracks to calm us down. This track was one of the things we did. I did a lot of ambient music with the first album, and continue to. Almost esoteric.

“Every so often we do a track that has a gentle feeling to it. It makes for a good break in the album. We need the record to flow. I was really into the idea of making albums that you’d play and listen to all the way through. It wasn’t about just playing one track and going ‘that’s my favourite’, and putting something else on afterwards. It was a reaction against what we’d gone through in the ’80s. So I think tracks like this were needed.

“I like it still. It’s a beautiful piece, based around real simple raw Karl guitar, and processing loops.”

Stagger

“This was done in two phases. Karl and I were upstairs in the bedroom studio and neither of us really wanted to work. I remember the day - I was feeling down and tired and Karl said ‘come on, let’s just put something down, even if it’s only half an hour’s work’. I remember just feeling really humpy [laughs], but getting on with it because it made sense. You don’t always write your best stuff when you’re in your best mood. It doesn’t work like that unfortunately. Get really happy and write a great song? I wish.”

“So that was the mood we were in and I began, like we always do, by firing up a quick rhythm track, a basic click and a kick and a woosh and a ding…then we played keyboards live over that. I think the main piano thing is the DX7 Mk1, which I’ve still got. It’s right up there, number two in my all time favourite keyboards.

“So, it’s live. We made it up as we went along. With Karl singing and no chord sequence. I trimmed it up a bit later, removing the odd bum note. It turned out to be one of my favourite tracks of that decade. It’s very me and Karl that tune. It’s our essence - the way it’s written and the strange intensity it has.”

Rick Smith on recording Second Toughest in the Infants

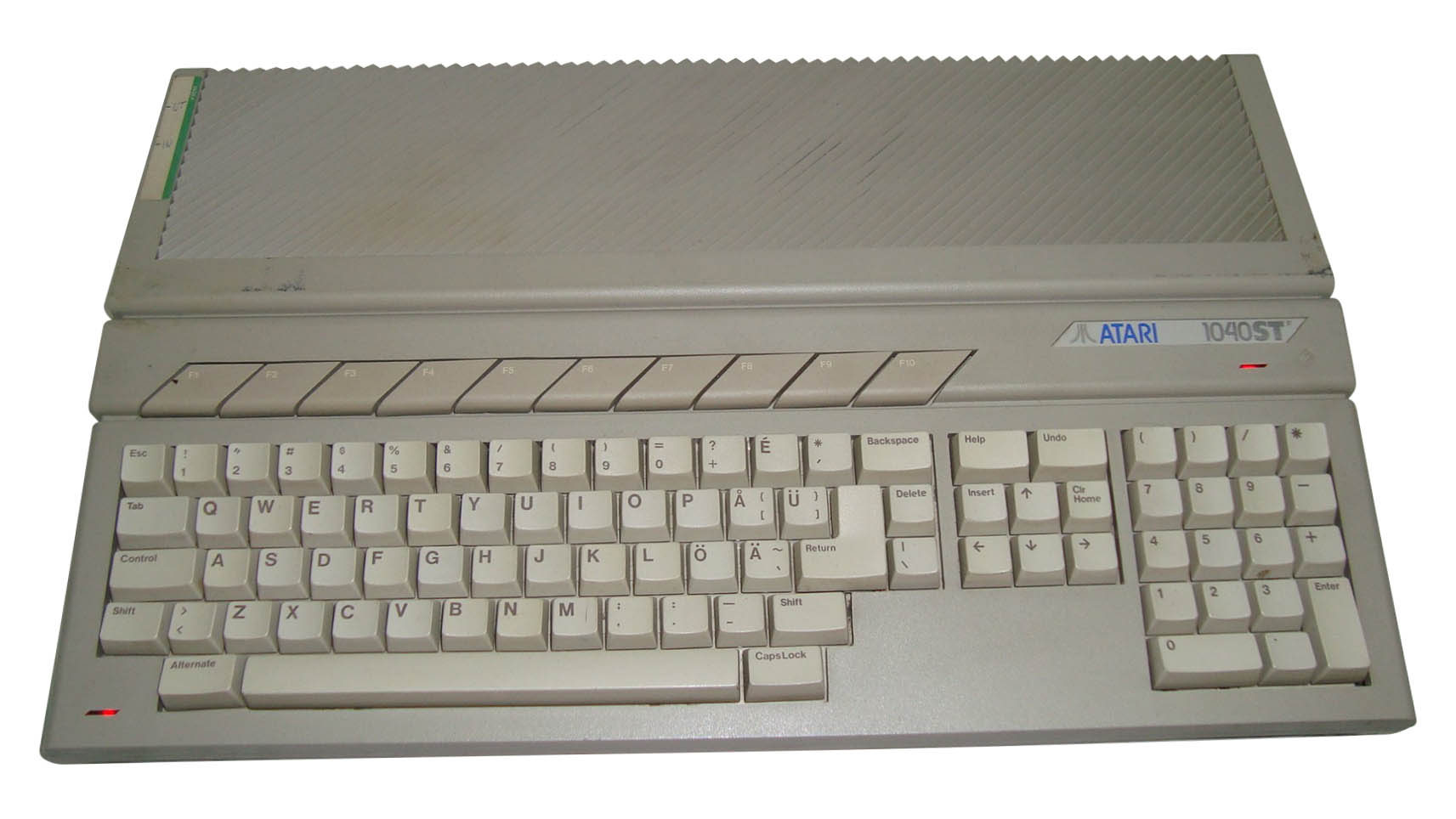

“The desk was a Soundcraft S600 series. Beautiful, very basic, kind of raw. We had an Atari ST 1040 computer, running C-Lab Creator, which was dynamite and I still miss it. Sound sources running through the desk were not all clocked off the same digital clock, so you got this magic appearing between space, which was lovely.

“I also used an Akai MG14D 12-track tape recorder, which was synchronised to the Atari with an old Fostex synchroniser. I could run a sequence and lock up tape at the same time. It was a bit touch and go. Sampling was limited. I had a Casio FZ-1 - I couldn’t afford an Akai S900.

“Mic-wise we had a Neumann TLM 170, which is beautiful, and we’re still using it. We also had the vocoder, an ARP 2600, an OSCar, 303s, 909s , a Nord for bass, a Yamaha DX7 Mk1, two [Yamaha] SPX90s, a Roland MT-32 unit and a Roland SD-3000.

“All the recording was done on an early Sony portable DAT machine, battery operated. There was no hard drive recording, although I rented one later to assemble the album and mix tracks together.

“Essentially, mixes were very live, through the console, running multiple MIDI and tape tracks, with effects live in the console. Very basic. One of the SPX90s ran stereo pitch, the other a stereo delay. Then the Roland SD-3000 mono delay line for feedback and dub delays. That was it. No plugins, no compressors, no gates… I don’t know how I did it!”