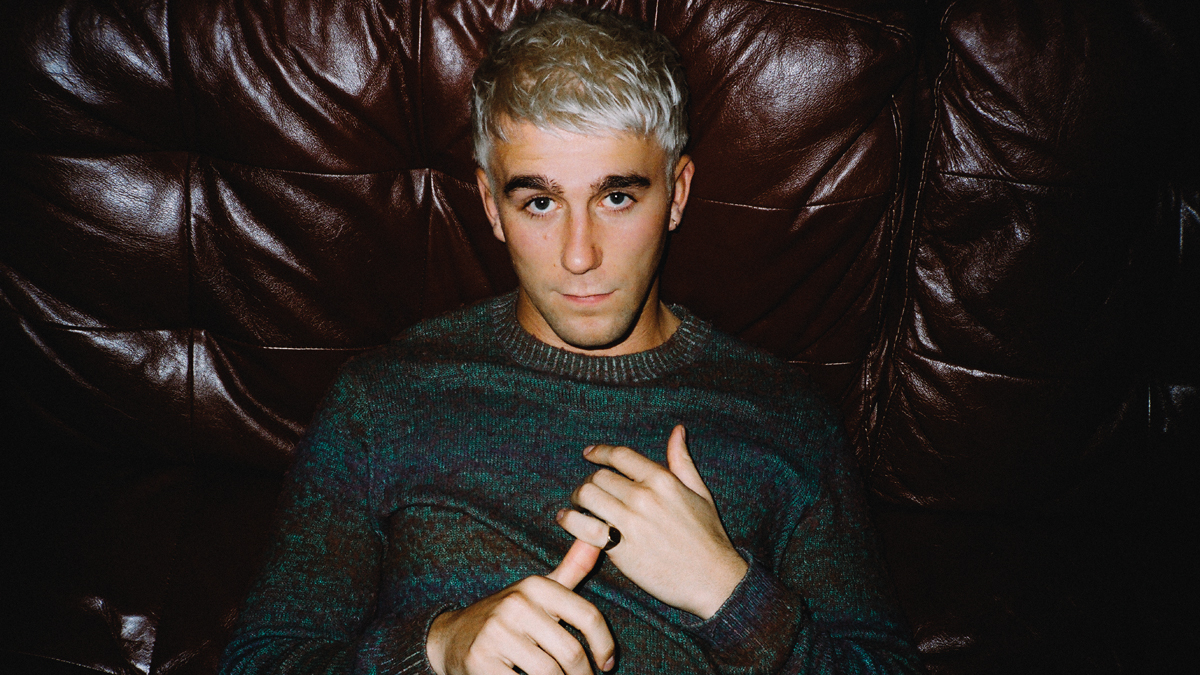

SG Lewis: “There are endless examples of incredible songwriters and producers who couldn’t play a C chord on a piano”

Honed in his parents’ attic and featuring a collaboration with Nile Rodgers, here’s the story of Lewis’s debut album, Times

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Club culture didn’t take hold of Sam Lewis until he studied sound engineering at university in Liverpool. Already possessing a keen interest in production, his eyes were soon opened to a world of dance music styles that eventually led him to secure a DJ residency at the now-legendary Chibuku nightclub.

With a plethora of singles under his belt and further traction via remixes for the likes of London Grammar, Flume and Dua Lipa, Lewis focused on recording his debut album last year. Encouraged to read Tim Lawrence’s Love Saves the Day - charting American dance music culture in the ‘70s - Lewis became infatuated by disco and set about creating his own interpretation.

The long-awaited album, Times, topped the UK dance chart in February. Featuring Grammy-award-winning hitmaker Nile Rodgers alongside numerous high-profile vocal collaborators, the 26-year-old has demonstrated his studio chops by co-writing, co-producing and mixing most of the record, while playing a plethora of instruments and making his debut as a vocalist.

Where did your love of production come from?

“I became curious about production because I was quite a shy kid, and although I grew in confidence as an adult, the idea of performing music was always quite petrifying.

“Once I found that a role existed where you could spend all day in a studio working behind the scenes, that sounded absolutely brilliant because I could make tunes and produce records without the flipside. I’ve ended up on stage doing something I really love, but I was just fiddling with software until I got to university.”

What happened at university to advance things?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I studied sound engineering and was surrounded by people who, to be honest, were a lot further along the path than I was. It was like a crash course and I became immersed in their world and obsessed with every part of it. I found so many people there who were tech-focused and wanted to take apart compressors and talk about the wiring as opposed to the latest hot drum sample. I’ve still got loads of copies of Future Music lying about and I skim the pages and read about how people are doing things.”

You began DJing at the Chibuku club in Liverpool. Did the music you were playing inform the style of music you wanted to make?

“Once I got to university I’d accrued enough confidence to DJ. I grew up in Reading but there wasn’t a huge dance scene so I wasn’t going clubbing. Once I got to Liverpool, alongside immersing myself in production, I discovered club culture. I’d come back from watching people DJ and dive onto the internet or look at YouTube tutorials to see how they were making house, techno or even dubstep. That informed my entire process because hearing those records made me want to make the music they were making.”

You’re not just a songwriter but sing and play a lot of instruments, including piano, bass and drums. Were those skills gradually acquired?

“I was playing guitar from about 10 years old in bands at school, so that was the first instrument to give me an understanding of music theory and songwriting, but it was only once I started producing that I realised that playing the piano was going to be really useful.

“I used to spend a lot of time trying to draw in MIDI by looking at chords I was playing on the guitar, but once I started doing songwriting sessions I realised I couldn’t really afford the time it took to translate chords into virtual instruments.

“Playing piano was a baptism of fire, but I started teaching myself and found I could also play bass to a reasonable standard. I’m not a very good drummer, but I can put down a 16th-note beat and definitely get something rough down.

“My approach is to just have a stab at everything and try and wing it - if it sounds cool, I’ll run with it.”

My approach is to just have a stab at everything and try and wing it - if it sounds cool, I’ll run with it.

Do you think that progression from drawing MIDI into a computer to playing an instrument substantially improved your songwriting?

“There are endless examples of incredible songwriters and producers who couldn’t play a C chord on a piano so, for me, it’s all about speed. When inspiration hits, it’s then a task of spinning plates until you arrive at the end goal of writing a song. Along the way, you might take a wrong turn and drop a plate, but being able to play basic chords allows me to get a vibe going quickly.

“If someone’s really rapid and can whizz through MIDI packs and shortcuts that’s great, but as I’ve grown more into the role of songwriter I also like being able to sit down at a piano and write without having to get my laptop out and get fully into my setup.”

Your debut album, Times, is influenced by disco music. Why take that particular direction and who influenced you generically?

“The whole journey began because I collected vinyl records; a lot of my friends traded them and spent weekends DJing in each other’s kitchens - pre-pandemic, of course. At some point, I started to find that a lot of my collection was made up of disco records, and the more I heard, the more I resonated with them.

“A friend of mine pointed me in the direction of a book by Tim Lawrence called Love Saves the Day, which is all about the history of disco in ‘70s New York. Once I’d read that and discovered where disco originated, it joined the generic dots and ten-folded my love of the genre. The book gave playlists by DJs like David Mancuso and Larry Levan, so I started to build my own Spotify playlist with records by Gloria Gaynor, Sister Sledge, Temptations, Jackie Moore, Chic and Nile Rodgers, and that was a lot to digest.”

Were you equally fascinated by how records were produced back in the ’70s?

“I definitely attempted to recreate disco tracks in what I thought was a traditional way, but I usually failed. I’d study the music but whenever I tried to replicate how it was made it wouldn’t sound right for a number of reasons, whether it was the session players, the preamps and mics they used or just those magical elements you can’t really explain. I remember being a bit frustrated by that and realised I needed to figure out how to process and present those influences from my own perspective, combining those elements with what I was capable of doing to create my own style.”

Ultimately, do you see Times as your homage to the genre, and NY disco in particular?

“I think it acknowledges what disco represented rather than the technical sound of it. As a result, some of those sounds do bleed into my reinterpretations, but I also became obsessed with the fact that disco soundtracked the celebration of safe spaces for marginalised communities. Disco parties were places that people from different walks of life and sexualities came together to create an inclusive atmosphere. Disco’s so joyous, and that became a focus as much as nailing the bass sound of something like Jackie Moore’s This Time Baby. ”

You’ve released a lot of singles over the past five years, so what did you find enticing about making an album?

“It was the first time that I wanted to communicate an idea, but didn’t think I could do that and cover every base. I’d done EPs and executed concepts on a smaller level, but once I jotted down everything I wanted to cover sonically on this album I knew that it wasn’t something I could do in four or five tracks or without visiting every different pocket. I thought, ‘great, I’ve finally got a reason to make an album’, and I’ve been pleasantly surprised by how much people resonated with that.

“I’d never put out a full-length body of work but the effect was a lot greater than anything I’d felt before in terms of the fans being on board with me. An album is like a commitment between fan and artist - you’re sticking a pole in the ground and saying ‘this is where I’m at right now musically’, and the fans give more of themselves in return.”

We’re guessing that the last track on the album, Full, is an example of a slow burner that you might not have otherwise made?

“Absolutely, because with an album you’re allowed a certain level of indulgence and Full fits into that because it talks about time as a finite concept.

“Sonically, it’s a lot different to everything else on the record. If I’d made an EP there’s no way it would have made it on there, and it’s cool that for some people it’s the track they love the most.”

Did the events of the last year affect the recording of the album or was it mostly wrapped up by then?

“Luckily, I’d done a lot of the songwriting prior to the first lockdown. Two tracks had some stuff to finish, which we did with the help of Zoom calls, but as I was locking down with my family I decided to start making music in the attic. I pretty much took a van and grabbed a load of my favourite synths from the studio, including the monitors, and tried to create my own setup.

“Having toured so much for the last couple of years I now had every day to myself locked in a room and it’s only now that I realise how large the task would have been to finish the production and mixing without that. In the end I mixed six of the 10 tracks on the album, with Nathan Boddy and Mark ‘Spike’ Stent mixing the other tracks between them.”

You must have been grateful to get the chance to meet Nile Rodgers pre-pandemic and work with him on a track?

“Nile Rodgers is a huge fan of championing new musicians and is so forward-thinking for someone who’s a legend and been such a big part of music history. He’s constantly collaborating with new artists and was doing a series of sessions at Abbey Road a couple of years back and inviting new musicians that he thought were cool. I was lucky enough to be included in one of those sessions with a few other people.”

Did anything materialise from that session?

“We worked on some stuff and it was a really fun day, but the record we worked on wasn’t used for any of my projects. Still, we got along really well and he told me that if I ever wanted to work on something together to just call him - and I was, like, ‘Err, great!’”

So later down the line you called him to work on the track One More?

“Julian Bunetta and I wrote the track in LA and I was playing the demo in the car about 100 times but felt there was something missing. It was actually my manager who suggested I send it to Nile, so we sent it over and he came back straight away and said ‘let’s do it’.

“We went back to Abbey Road and he played a bunch of guitar on the track but also had ideas about where it could go in terms of sound structure and production. What he added was invaluable.”

What key thing did you learn from Nile?

“I interviewed him recently on Zoom actually and he said something that stuck with me. He’s had hit upon hit over the decades but to this day still has no idea whether something will become a hit or not.

“For instance, when he wrote the two records with Daft Punk they were convinced that Lose Yourself To Dance would be a global smash and Get Lucky was just a cool warm-up track. If you go back on YouTube you’ll see that the expensive video was made for Lose Yourself to Dance, not Get Lucky. As Nile mentioned, all you can really do is follow your gut and make the music you like.”

The industry is strewn with stories of artists trying to make music to fit what they thought would be successful, and typically failing…

“I don’t think people give the public enough credit because they can sense ingenuity a mile-off. All that music really needs to do to be successful is make people feel the way you felt in the studio.

“The industry has such a focus on a particular person being hot and then judging them because they ‘lost it’, but no one ever loses it - their ability doesn’t change and they don’t forget how to make music, they just haven’t produced their best work for whatever reason. That could be down to how in touch they are with their creativity at the time, what’s going on in their life or other unquantifiable things.

“As soon as music becomes business it becomes the antithesis of creativity, so there should be less focus on hot streaks or ‘flop eras’ and musicians just need more faith in their ability. Even if they go six months without making something they like in the studio, they will eventually.”

All that music really needs to do to be successful is make people feel the way you felt in the studio.

On this album we understand you wanted to impose your own vocals on the music more than previously?

“I’m singing on half the album, so I was really happy about that and I’ve come out the other side a much more confident singer.

“I’m sure a lot of production-focused studio rats will resonate with this, but the idea of singing was alien to me at university - I would have laughed in your face. It was always something I wanted to do but didn’t have any confidence in.

“Everyone has a voice; you’ve just got to learn how to sing in tune and there are obviously lots of tools to help. I know that I’m not going to rip my way through any Whitney Houston vocal scales, but I can use my falsetto in a way that sounds cool in certain registers.”

Still, it’s quite a brave leap to suddenly start singing six years into your career?

“You can’t be scared. I was in the studio with a pop act recently who’s an amazing singer, but halfway through communicating a vocal idea my voice went all over the place. Five years ago that would have killed me - I’d have gone bright red and left the room - but it happens so often now that I just laugh and carry on.”

And perhaps recognise that some of the most successful artists weren’t the greatest singers in the world, either?

“I don’t think any of my favourite singers are great technically. There’s a big difference between being a singer and an artist communicating and transferring emotion through their voice. I love Bon Iver and wouldn’t pick Justin Vernon as the most vocally gifted singer, yet I think he has the most emotionally powerful voice of anyone.”

Presumably, adding vocals also means writing your own lyrics, which enables you to connect with a song better?

“Absolutely - I didn’t want to start singing to say, ‘woo-hoo, look at me, I did it’; it’s because I felt I had things I wanted to say that would be best coming from me. It opened up a different aspect of being an artist because I’ve always loved production, but when you unlock the ability to say things you suddenly realise you can use your music as therapy.”

You’ve always worked with a lot of different vocalists and Times is no exception. How would you typically go about sourcing vocalists for your projects?

“I listen to an enormous amount of music because I really like doing that, so it’s literally just a case of me hearing someone and imagining them being great on a particular track or record.

“A lot of young producers don’t sing but want to work with people, and that can be done at any level. When you’re starting out it’s obviously going to be a lot harder to get a huge pop star to sing on your track, but on SoundCloud there are endless great singers who you can hit up.”

On a similar topic, could you explain what informs your choice of co-writer?

“Songwriting Is a dark art and I couldn’t really tell you to this day what makes some partnerships work; you’ve just got to try and a lot of the time it’s about finding people who do things well that you don’t. There’s no use both of you being incredible melody writers or lyricists - you want someone to fill the gaps, and good partnerships happen when people complete each other as a duo.”

The track Time features seven different writers. How do you stick to your initial vision of a song with so many people having input?

“It started from a Dennis Edwards sample so writers from that song are credited, then Orlando had a piano loop he’d worked on that I used, and Julian and I were hanging out in Nashville making loads of music. And I loved an instrumental part I’d written and sent it to Rhye for their vocal contribution.”

You use a couple of studios, one being newly created at your parents’ home?

“I moved out of the London setup before the first lockdown and had been floating around studios for a bit because I want to build my dream studio in the next two years. So my setup has been quite mobile and consisted of a few key things placed in different rooms.

“Right now I do a lot of the grunt work in my parents’ attic, but I’ll be moving into Sleeper Sound for a few weeks and also a residential studio called Decoy. If you repeat the same processes you get the same results, so I often get bored of my own productions and the best thing I can do is change my environment and the toys I’m playing with.

“I went to Angelic Studios at Christmas, which was owned by Toby Smith of Jamiroquai. It has all the synths he used to use before he tragically died, and that opened up a whole new world of opportunity.”

You mentioned having some key gear that you transport around. What does that consist of?

“I can’t go anywhere without my Dave Smith Sequential OB-6 - it’s the ultimate synth! It’s so versatile and I know it so well that I can get whatever sound I need out of it most of the time.

“I take my UAD Apollo Twin everywhere I go, as it’s a flawless audio interface, and my ATC SCM25A Pro speakers because the clarity of the top end changes everything from a mixing standpoint, especially when I’m working on pop stuff.

“Recently, I’ve enjoyed using the Korg MS-20 Mini as it’s got a screaming resonance. White noise samples can be cheesy, so the MS-20 is great for building your own transitional sounds and zaps and stuff.”

What’s your go-to software these days?

“I’m definitely into my plugins and I’m indulging my analogue synth side a bit more these days. I use all the NI stuff like Massive and Reaktor, and Arturia does really great replicas of all the classic synths, but my argument for hardware isn’t from a sonic standpoint, it’s about having something in front of you that you can grab and make things happen with a lot quicker. That lends itself to creativity.”

What are you using for recording?

“Logic has always been my home DAW, so I was using Logic X until my good friend Guy Lawrence from Disclosure showed me how to use Ableton Live. As I’ve got more into disco and working with breaks, I’ve found that Ableton’s time warping algorithms are far superior to Logic’s, but because I’m so stuck in Logic in terms of my process I didn’t want to make the full jump. Now I use Ableton for all my audio manipulation and ReWire for the outputs into Logic.”

We guess you’ve scratched the disco itch with this album. Have you got any further ideas about how you want to develop your sound moving forward?

“When you study an era like that and ingest its influence it’s never going to disappear. While the sound of disco might not necessarily be at the forefront of my mind, it will always be part of my musical education. I’ve got a pretty good idea of where I’m going next and I’m already a couple of songs into that, but I wouldn’t want to reveal anything too soon [laughs].”

The SG Lewis album Times is available now on EMI Records/PMR. For more, visit SG Lewis on Facebook.