'As time has taught us, there was a lot more to Kurt Cobain’s guitar playing than the slacker attitude he’d like us to have believed': 5 Nirvana songs that celebrate Nirvana's legacy

'He was a phenomenal rhythm player, clearly had some lead playing ability, and also experimented sonically – with fascinating results'

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

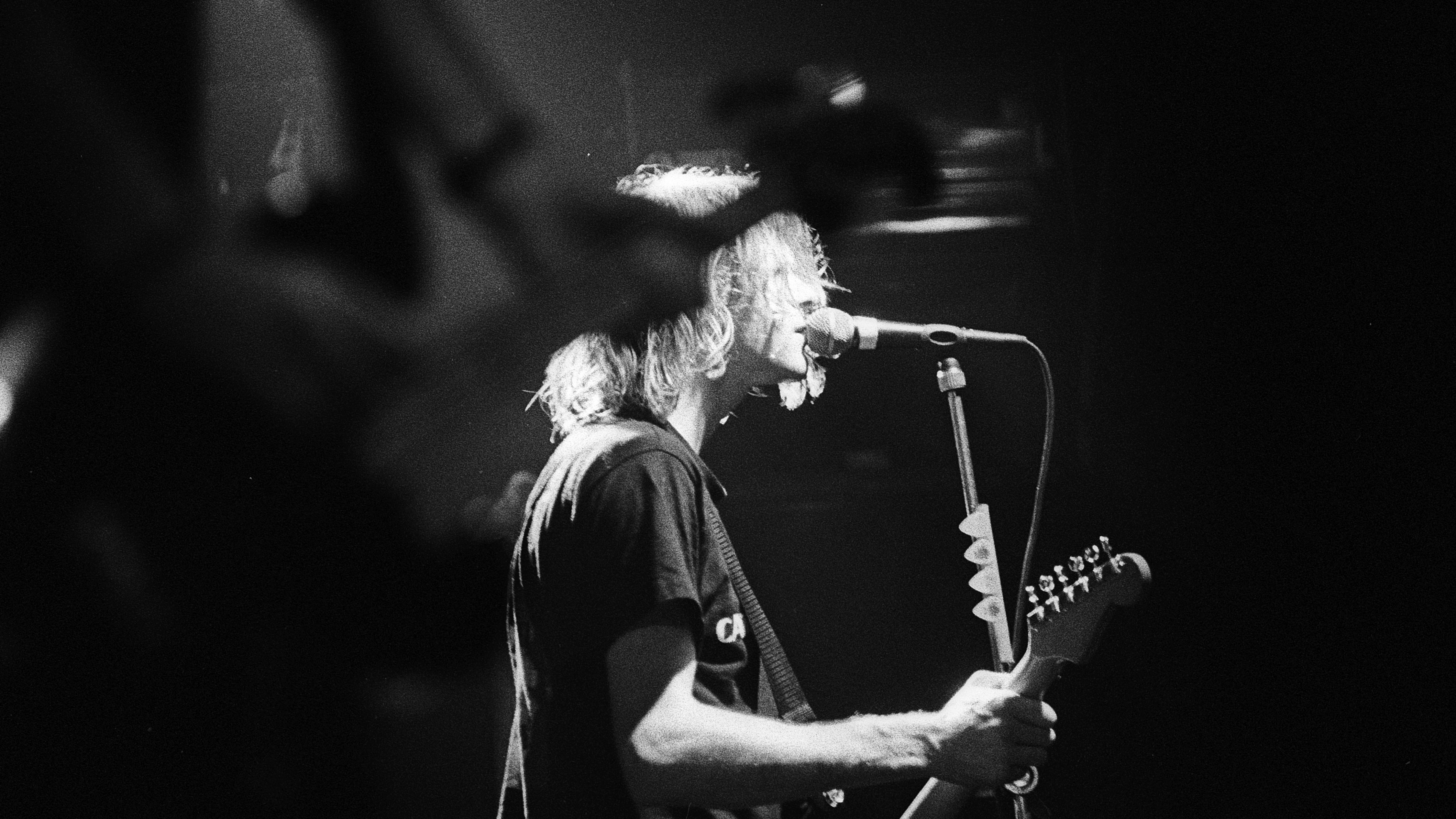

Believe the legend and the image that Kurt Cobain presented, and he was the antithesis of a guitar hero – a punk rock purist valuing spirit and a bloody good racket over technical ability.

But as time has taught us, there was a lot more to Kurt Cobain’s playing than the slacker attitude he’d like us to have believed, he not only listened to but loved The Beatles, named a song after Aerosmith and Led Zeppelin and sometimes showed a clarity and precision to his playing that doesn’t come without putting in your 10,000 hours.

His was a bigger picture, plotting out Nirvana’s rise to glory in his journals while half-feigning complete surprise and even resentment at the band’s success

But Cobain’s dedication to his craft clearly lay outside of woodshedding guitar histrionics, he was a phenomenal rhythm player, clearly had some lead playing ability, and also experimented sonically, with fascinating results. But his was a bigger picture, plotting out Nirvana’s rise to glory in his journals while half-feigning complete surprise and even resentment at the band’s success – perhaps misdirected frustration at the subsequent attraction of the type of fans his songs derided.

You know the four chords of Smells Like Teen Spirit, the Page-One riff of Come As You Are (which also saw the band sued by Killing Joke), but there’s a lot more to Nirvana for guitar players to absorb than just the big radio hits (although we’ll take a look at a couple of those too). Join us as we pick out some essential listening

1. Lithium (Nevermind, 1991)

We’re all familiar with Nevermind, either on cassette, CD, vinyl or all three, and while none of the songs from the album should require an introduction (least of all a single), but let’s just take a moment to appreciate the brilliance of lithium. First off is the clean Strat tone, all necky, hollow and, as with many of Nevermind’s clean sounds, slightly watery. Cobain’s glissando rolls between the chords with a plucky tone that we’ve never really managed to recreate, and it’s our first proof of his under-sung rhythm abilities and attention to detail with his guitar playing.

The bass also highlights Nirvana’s love of The Beatles - the plodding descent overlapping with Kurt’s rhythm part to create a delicious counterpoint that’s (whether by conscious design or not), straight from the Lennon/McCartney playbook.

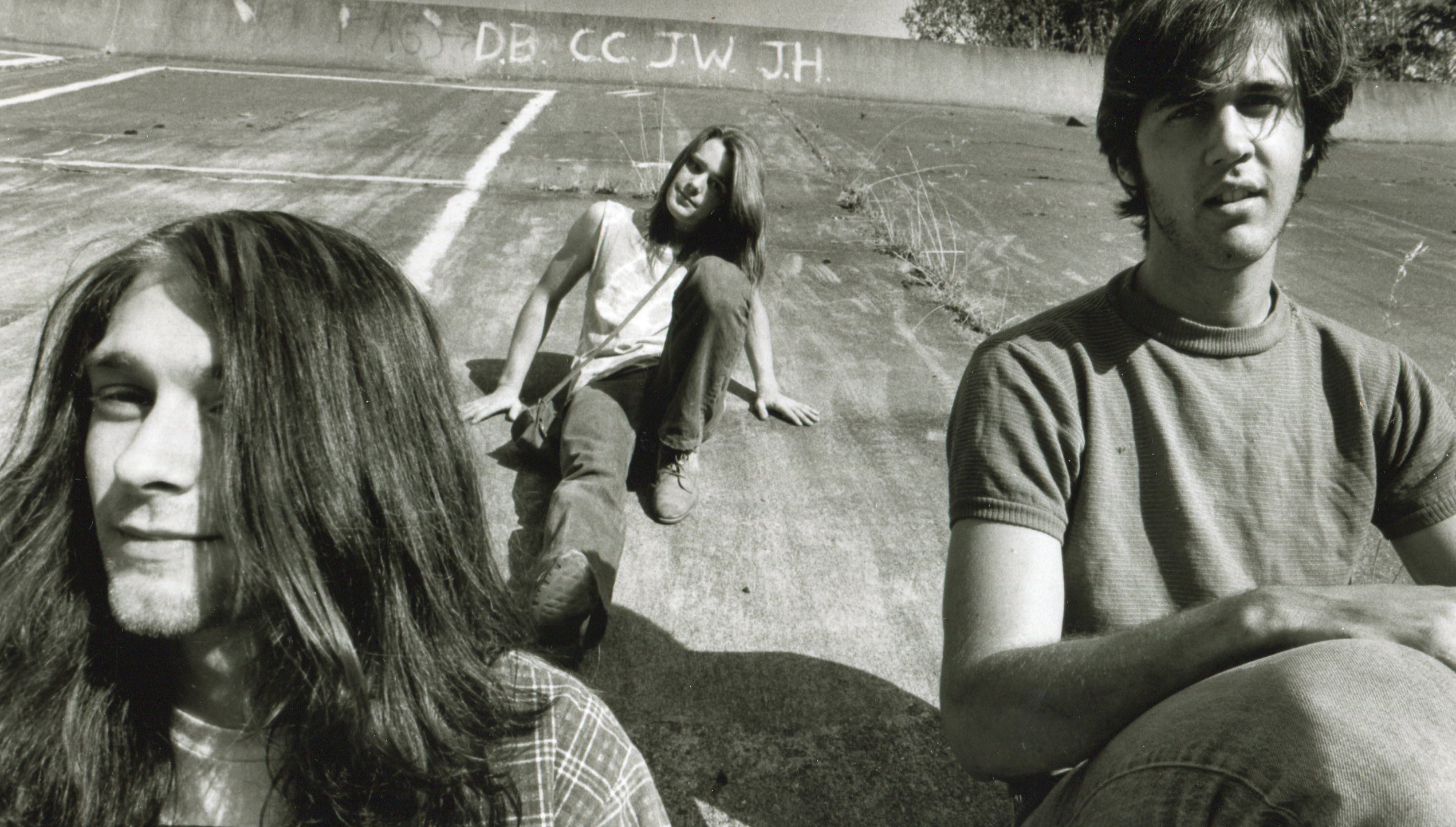

Nirvana's 1990 sessions with drummer Chad Channing that shaped Nevermind

Cobain’s guitar sounds on Nevermind were a mix of his Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier preamp/Crown power amp into a Marshall 4x12” cab, a Fender Bassman and a Vox AC30. As well as Kurt’s Boss DS-1 distortion pedal, the band and Butch Vig concocted a dirty sound which they nicknamed the Super Grunge - featuring an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff running into the Bassman. “We used an Electro-Harmonix Big Muff fuzz box through a Fender Bassman on Lithium to get that thumpier, darker sound.”, Vig told Guitar World.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Lithium also inadvertently gave birth to the album’s secret track, Endless Nameless, which was born out of Cobain’s frustrations while recording Lithium. After countless re-takes, Cobain launched into the jam, which culminated with the smashing of his Strat in the studio, a tactic that the band would go on to employ frequently at live shows.

2. Sappy (Various)

Sappy is one of the most interesting ‘other’ songs in the Nirvana canon for various reasons. First is that it emerged during one of Cobain’s purple patches, where the songwriter unstoppably penned earworms. When you’re discounting songs as strong as this from proper releases, you know you’re on a roll.

And discount it, they did, but not without trying first. As well as Cobain’s home demo of the song, Nirvana made four studio attempts at Sappy between 1990 and 1993: two with Bleach drummer Chad Channing (recorded by Jack Endino between the Bleach and Nevemind sessions, and again for the Smart Sessions with Butch Vig), then twice more with Dave Grohl during the Nevermind and In Utero sessions with Vig and Steve Albini respectively. None of these recordings ever found their way onto a studio album, and the Grohl Nevermind-era session is still yet to be released in any form.

Sappy has the hallmarks of Nirvana - clean into huge distorted power-pop, verse/chorus/verse structure. But it also strays from the layman’s idea of Cobain’s playing - there’s no four-chords-over-two-bars chord progression, instead the changes loosely follow the rhythm of Cobain’s vocal shifts.

Then there’s the solo. Throughout Cobain’s career he presented the idea that he had little knowledge of the fretboard, and barely any respect for lead playing ability within the context of his band. However glimpses here and there betray this - the fast runs displayed on Nirvana’s cover of Shocking Blue, the well-constructed melodic solos on hits such as Smells Like Teen Spirit and Heart Shaped Box, and probably the best evidence of all, the solos on In Bloom and Breed.

A comparison of the Smart Session versions to the Nevermind release versions of these two songs confirm that his chaos was indeed composed at times

Cobain had a knack for making his solos from random noises, atonal feedback and seemingly unrehearsed, and most-likely unrepeatable. A comparison of the Smart Session versions to the Nevermind release versions of these two songs confirm that his chaos was indeed composed at times. Sappy follows the same path - albeit more melodic - and while the note choice might be unconventional, it fits Cobain's pattern perfectly.

3. All Apologies (In Utero, 1993)

Following the monumental success of Nevermind, Nirvana enlisted Steve Albini to record the follow-up, In Utero owing largely to his work with The Pixies on Surfer Rosa, and Cobain’s desire to push back against the radio-ready production of Nevermind.

Albini’s now-legendary engineering techniques (including extensive ambient microphone placement) resulted in a much more natural sound to the recording than its predecessor, to the point of the album being described as ‘unreleasable’ by Geffen executives, resulting in Albini temporarily withholding the master tapes before REM producer, Scott Litt was called-in to remix Heart-Shaped Box and All Apologies.

There are plenty of versions of All Apologies to immerse yourself in, from the slowed-down, home demo with different lyrics (“What else could I write/I don’t want to fight”) through the In Utero studio version and the masterful performance delivered for Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged recording.

From a guitar-playing perspective, the droning bass note accompanied by the almost-classical melodic run that makes up the song’s verses and hooks, stands slightly alone in Nirvana’s catalogue.

Once again, with the help of Kera Schaley’s cello (Lori Goldston would play the part live), Kurt Cobain displays his uncanny ability to make melancholy feel sublime, and while it’s not a Van Halen-level technical display, he also often chose to play the riff live while singing - despite hiring later-era second guitarist Pat Smear specifically to remove pressure from his guitar/vocal role in the band (although he takes a simplified role during the Unplugged performance).

Kurt Cobain wrote a song with a I IV V progression, just not as you might have imagined, turning what could have been a simple cowboy/blues progression into a haunting confessional

When it shifts to the chorus, All Apologies shows us yet again that Cobain’s insistence on simplicity was core to the Nirvana sound and success, remaining on the G chord for what feels like forever, building the tension with before resolving to the A. Yes, Kurt Cobain wrote a song with a I IV V progression, just not as you might have imagined, turning what could have been a simple cowboy/blues progression into a haunting confessional. And therein lies his genius.

About A Girl (Bleach, 1989)

“This is off our first record…most people don’t own it.” Cobain announced bluntly before launching into the sublime Unplugged performance of About A Girl. It was a show that had MTV executives in doubt right up to the opening chords, and would set the bar for what could be achieved in the ‘stripped-down’ format.

No Smells Like Teen Spirit, no celebrity guests. Instead, Cobain dressed the set like a funeral, covered The Vaselines and brought on The Meat Puppets to play songs that nobody had heard of. And it was a career-defining triumph. But About A Girl is important because it was reared long before the hype of Nevermind.

At just $600, Bleach cost almost exactly 100 times less to record than Nevermind, and to many, it’s the quintessential sound of the band with its grinding, heavy, detuned riffs - fuelled by Cobain’s Univox Hi Flier, DS-1 and a Fender Twin belonging to producer, Jack Endino. While there’s plenty of solid guitar work on the album - Blew’s main riff/vocal mirroring, the impossible counter-rhythm of Swap Meet’s guitar against Kurt’s voice, and the bluesy finger twist of Mr Moustache - Cobain’s songwriting style was still to be refined in some ways..

Sticking out from the pounding sludgy-ness of Floyd The Barber and discordant parts of Paper Cuts is About A Girl. Apparently written about Cobain’s then girlfriend Tracey Miranda after she protested that he never featured her as his muse, the ‘I can’t see you every night’ line was presumably not the flattering love song she was looking for (see Clean Up Before She Comes for an even less complementary view).

A childhood of listening to The Beatles comes flooding out from the guitar parts

The jangly clean sound of the Emin/G intro and verses, met with the sweet chiming backing vocal and, gulp…tambourine give us an early sense of Cobain’s love of pop music that we’d see more of later. A childhood of listening to The Beatles comes flooding out from the guitar parts, giving us a beat combo-style rhythm, a simple melodic solo over the verse and spreading out over the chorus chord progression - itself taking us on a slightly jarring, yet still pleasing key shift - , followed by a build-up leading us into the outro.

Check out the Unplugged in New York version for a more explicit use of the dominant chords that are implied on the Bleach version. If Lennon and McCartney had grown up in Aberdeen, Washington, we think it would have sounded like this.

5. School (Bleach, 1989)

As noted above, Bleach was full of heavy riffs, the low-tuned, fuzzed-up sound of Sub Pop bands at the time giving birth to the Grunge moniker. School joins Negative Creep in the stoner section of Nirvana’s catalogue with its hypnotic riff displaying a jerky, syncopated rhythm, capped off with a subtle vibrato on the final note before it erupts into uncharacteristically stadium-like ringing chords of the chorus.

It’s a short song, but one that would stay in Nirvana’s live set right up to the end,

The solo is another example of Cobain’s classic rock ‘guilty pleasure’, starting with a psychedelic extension to the main riff before going full Woodstock with big bends, and the type of noisy Cobain lead runs that are almost sarcastic in their delivery. The anti-guitar hero showing contempt for big solos by taking one, but choosing to massacre it rather than take it seriously. performing it at both of their triumphant Reading performances, as well as their final ever gig at Munich’s Terminal 1, 1 March 1994.

Stuart has been working for guitar publications since 2008, beginning his career as Reviews Editor for Total Guitar before becoming Editor for six years. During this time, he and the team brought the magazine into the modern age with digital editions, a Youtube channel and the Apple chart-bothering Total Guitar Podcast. Stuart has also served as a freelance writer for Guitar World, Guitarist and MusicRadar reviewing hundreds of products spanning everything from acoustic guitars to valve amps, modelers and plugins. When not spouting his opinions on the best new gear, Stuart has been reminded on many occasions that the 'never meet your heroes' rule is entirely wrong, clocking-up interviews with the likes of Eddie Van Halen, Foo Fighters, Green Day and many, many more.