Neil Cowley on playing keys for Adele's biggest singles: "I did three afternoon’s work and spent the next ten years listening to myself in supermarkets"

Struggling to confront the past, Neil Cowley’s second LP, Battery Life, attempts to redefine his memories. Danny Turner chats to the acclaimed pianist

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With his skills as a keyboardist in heavy demand, classically trained pianist Neil Cowley began his career as a session musician working with bands such as The Brand New Heavies and solo pop idols Emeli Sandé and Adele.

With his own band, the Neil Cowley Trio, the critically lauded composer has straddled the pop, jazz and experimental genres with ease, releasing a host of albums concluding with the jazz instrumental masterpiece Spacebound Apes in 2016.

Not far shy of his 50th birthday, Cowley pivoted towards working on a solo project, releasing the more electronic-focused LP Hall of Mirrors. Enlivened by a renewed sense of self-expression, he returns two years later with the soothing brilliance of the electro-acoustic Battery Life – an album that examines the positive/negative balance of abstract memories; memories that were often too painful for Cowley to face.

The piano is obviously integral to your creative output. What is it about the instrument that has you hooked?

“I was the definitive classically trained piano kid. My father used to have parties at our house and installed a little Zender upright piano. By the age of five or six I was making little tunes and eventually went to see this dear old lady who would give me marks out of ten every week before professing to my mother that this boy’s got talent.

“Then a very kind man who used to play hymns in assembly plucked me out and said, ‘We’ll train this boy and get him into the Royal Academy’. I think I was a bit of a social experiment because when I got there everyone was super upper class and all seemed to know each other. I kind of hated it but just by chance I joined a Blues Brothers covers band when I was 14 and that changed my life. From that moment, I taught myself everything about contemporary music and piano and was hooked.

“In terms of sustaining it, I don’t sustain a love for it through thick and thin – there are huge swathes of time where I loathe everything about it, but that’s normally when I loathe everything about myself. The piano is integral to me and a reflection of who I am and how I feel about myself more than any other item in my life, so when I’m in love with myself I’m in love with the instrument.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Didn’t you get into programming at that point too?

“I used to get these little ZX Spectrum magazines where you could manually type in code. There would be five or six pages of endless script and you’d get three quarters of the way in and the computer would overheat and crash.

“I don’t remember anything ever happening as a result of spending nine hours doing it, I suppose it epitomised how lagging I was in terms of technology. Because the piano was my main source for music, it took me years to work out you could do cool things with electronics.

“Eventually, I did two paper rounds, saved every day and got myself a clunky old digital Yamaha DX7, which gave me a portable piano to play with in the soul band. There were also books where you could programme stuff into the DX7 and save it onto a ROM, but I had no idea what I was doing with that either.”

Did you try your hand at solo recordings prior to becoming a session musician in your late teens?

“Someone lent me a 4-track machine once and I’ve got some cassette tapes withering away in lofts, but as a teenager my goal was just to find a gateway out of my social situation. The way to do that was to just get out there, see the world and make a living by playing with other people in bands.

“I answered a Melody Maker advert for a keyboard player for a ‘chart band’, which happened to be The Pasadenas, who were five guys from London who were kind of like The Temptations. Every keyboard player in London seemed to audition for it but I somehow got the gig, which was enough to get me into a session agency called Session Connection.

“The first audition they got me was with Marcella Detroit from Shakespears Sister. That didn’t work out, but the second one was The Brand New Heavies – a band that I’d been to see and loved. I got that gig!”

Can you take us through the process of contributing to Adele’s first two albums, 19 and 21?

“At that point I’d turned my back on session work because I’d started the Neil Cowley Trio and was spending all my time doing that. Then an old friend of mine who was managing a producer called Jim Abbiss rang me to say she had this act who was only 17 and it was her first time in the studio but her keyboard player left because he didn’t think it was going anywhere.

“I turned up to find Adele and we set up either side of the room and did Hometown Glory in two takes. All the other stuff was overdubbed at a later date and I repeated that process for the second album, 21.”

The environment around the second album must have felt very different?

“Thinking back, the Adele phenomenon still hadn’t quite kicked in yet. 19 had done very well but it was only after 21 came out that everything went ballistic. I did Rolling In The Deep with Paul Epworth on that one, which was a slightly different process. Basically, I did three afternoon’s work and spent the next ten years listening to myself in supermarkets.”

Having contributed to such seminal albums, does

that leave you with a feeling that goes beyond it being just a ‘job’?

“The process is quite liberating because you don’t have to attach parts of your soul to it – the irony being that those few afternoons left a massive imprint on the world whereas I pain over my own stuff, which means so much more to me but doesn’t have the same outcome. The Adele stuff cuts a conversation dead at dinner parties when you don’t know what to say about yourself, but although I’m disconnected from it I suppose there is some pride in the gravitas of how iconic it’s become.

“Because it’s not from the most private parts of my heart, I can objectively say I’m very good at playing piano on a pop ballad because I have everything I need technically, my ear’s really good and I understand how to complement a voice. It comes from a part of my brain I’m not shy of, but that confidence goes to shit when it comes to working on my own things.”

Does that lack of confidence explain why you didn’t record your debut solo album Hall of Mirrors until a few years ago?

“I loved the human interaction of playing in the Neil Cowley Trio and was conceited enough to stick my name all over that because it was my compositions and very much my creations, but you’re right that I didn’t make a solo record until quite late.

“We’re sitting here now in front of these TVs that I’m able to play with my piano. In a way they’re like pseudo band members; I can interact and make them do things that feed back to me. That’s the advantage and joy of being in band – there’s always someone to trigger an idea or raise your energy, but being a solo artist is a lot more difficult, particularly live.”

Have you found that working solo is a freeing experience or is it more creatively challenging having to start from a blank page with no one to feed off?

“It’s hideous at first. All those safety blankets are no longer there so you feel very exposed. That was what made Hall of Mirrors and my latest album, Battery Life, the most personal, intimate and open records that I’ve ever made.”

You mention Battery Life being a record of ‘abstract memories and stolen excerpts’. That’s quite an abstract description in itself…

“It all spawned from reflecting on my mother’s diaries. She died in 2010 after a very long illness and left me a big pile of diaries that she used to write year-on-year. I didn’t have the courage to read them, mostly because I had to nurse her psychologically through the last ten years of her life fighting this horrible illness called fibrosing alveolitis.

“Whilst I did everything I could, I was scared that I might read that she was disappointed in my performance in some way, so I was being a coward and denying myself that, just in case there was a stab in there. It made me reflect on what an archive or a memory is and how I would view what my mother documented in a very detailed way and the emotions that would unearth.”

Do you think that how we archive memories often misrepresents them?

“We record every single moment of our lives on our phones and devices, but is that as powerful as what we selectively remember and are those abstract memories actually more powerful, romantic or suggestive? Why do we have to document everything in such detail instead of just living to remember what we remember?

“The ultimate example of that is being at an amazing event and filming the whole thing through a phone where you miss everything just to tick a box saying that you were there.”

Typically, when you look back at the footage it feels disassociated.

“There’s nothing there – no soul or emotion. I reflected on that a lot and actually did a little second album for the CD version of Battery Life. I didn’t listen to the record for three or four months after I finished it then took a few select stems, played them through the Mac and created entirely new tracks based on those few memory triggers, experimenting and reflecting on whatever my brain had retained.”

Once you had a concept for Battery Life, how did you begin to unlock those emotional themes in practical terms?

“The piano does that for me anyway. To be absolutely honest, it’s not as convoluted as thinking about what I did on a particular day in 2006. I’ll create some work and tend to posthumously process what I was thinking about or what was playing on my mind at the time. Playing piano is an abstract process that’s more in touch with my subconscious than I am consciously. In that sense, I’m behind my own brain.

“Some days you sit down and memories are just there, other times you have to use that dirty word ‘practice’. You practise for an hour and suddenly you connect with something and have shitloads of ideas. On other days, I’ll drive an hour to get to the studio, realise nothing’s there and go home again – and that’s tough.”

Was there a point where you felt you went beyond various classical or contemporary influences to discover your own unique voice?

“There is a voice of my own and I have pondered on what that is – it’s having eclectic musical tastes and someone who was fundamentally taught how to play classical music and eventually conjured up a love for it. Perhaps controversially at this point, I’ve always been fascinated by the more Russian-tinged Eastern bloc classical stuff like Shostakovich, but my father was a jazz-pianist, my mother was obsessed by jazz, and soul music was my personal little place.

“The lyricism of soul and jazz and the technical harmonic know-how of classical is the mish-mash that I am, but on reflection everything I’ve done is part of the same body of work. All I’m doing is using different tools and flavours to plunder different angles.”

How do you prevent your use of piano from becoming habitual?

“There are days when I ponder that very question: ‘I know your licks, Cowley – come on, do something different!’. I suppose that I have faith that my chords and phrases are me and that I have enough breadth of language to express myself through them.

“How you stop it becoming habitual is a good question. Listen to others, I suppose. Listening to things that stretch the mind, working them out, copying them and making them your own is one technique to getting through that.

“My Achilles heel is that I see a new piece of gear, buy it and ten minutes later I’m bored of it. Inevitably, I realise that I was fine where I was with the instrument that I love and know the most, but maybe I needed to go around all of those circuits to get there.”

When did you move into Metropolis Studios and what made it such a good choice for you?

“I had a studio at the end of my garden for ten years but contrary to everyone else’s experience, decided that I needed an hour’s commute to get my head together. I approached the previous MD around 2018, looking for a space, and he said they would build some studios in the basement. A deposit was given but a year later not a single brick had been laid, although they eventually created this lovely big room at a very kind price to compensate me. Now I can’t leave – it’s the cosiest, friendliest room in the building and it’s got all my vintage keys.”

Do you tend to bump into a lot of other artists?

“Last week The Rolling Stones were in with Elton John and Bill Wyman was even back in the fold. The Foo Fighters turned the whole place into a rehearsal space for their Wembley Stadium gig, so Queen, Black Sabbath, Paul McCartney and Stewart Copeland were all in. Although there are parts of the industry I like to keep at arm’s length, it’s still nice to see them in the cafeteria.”

You mentioned having an addiction to new gear. How has that manifested?

“I wish I knew my limit, I just keep going and going and now I’ve got a lock up to keep certain stuff. The band Genesis had a clearout of their studio, which happened to be in the village where I live. I was fourth or fifth on the list to pillage what they were selling but I still managed to grab a load of their stuff including a Yamaha CS-80, Prophet T8, a pair of Tannoy speakers and Tony Banks’ Fender Rhodes.

“I filled the room, but now I’ve decided that space is more valuable than gear because it gives you time to work out exactly what you’re doing. The sideshow of this solo album is that I wanted it to have an electronic vein so I bought every piece of electronic equipment I could lay my hands on, yet ultimately ended up at the piano again.”

What piano do you use?

“It’s a Kemble, which I bought as a stop gap 15 years ago. Kemble has a reputation for being a poor man’s Yamaha, but I got lucky. The piece of felt that goes across the hammers gives it a beautiful celeste-type quality. Upright pianos are extremely brittle, but when you put the practice pedal on it completely embraces you.

“Virtually everything I’ve recorded has been on this piano – it’s been so lovely to me. Having said that, Metropolis Studio A does have a big grand piano if I want to use it – sorry Kemble [laughs].”

What’s the attached interface?

“It’s a Helpinsteel piano sensor made by Mr Helpinsteel in Austin, Texas. It’s a big magnetic pickup that goes across the board, gives you a very reliable piano sound and avoids any feedback issues because it uses a contact mic. I use it as an interface to plug into a bunch of guitar pedals, which allows the piano to play a million different effects too.”

Have you tried software emulations of piano?

“I find the best software emulations of piano tend to be the ones that aren’t trying quite so hard to sound like a piano. The Nils Frahm Una Corda is pretty good, but something in my ear gets bored very quickly as there’s a finite amount of sounds.

“With the Kemble, it depends on the room, the mood, the heat and how the hammers hit the strings. The feel of plastic on a wooden bed is analogue and gorgeous and embraces your fingers in a completely different way.”

Do you supplement the sounds on the album with a lot of software sound design?

“The piano is generally the first thing that goes down and then I’ll work around that, but 95% of what I use is hardware-driven. My 1973 Minimoog is a mainstay for bass parts and I love the new Dave Smith Prophet ’08 and Moog Grandmother. I play with those and stick them through various combinations of effects, compressors and EQs, like most people do.

“I spend a lot time syncing things up because something new happens every day when you do that. There are too many temptations within the digital world to make everything sound perfect and I tend to shy away from that as much as possible.”

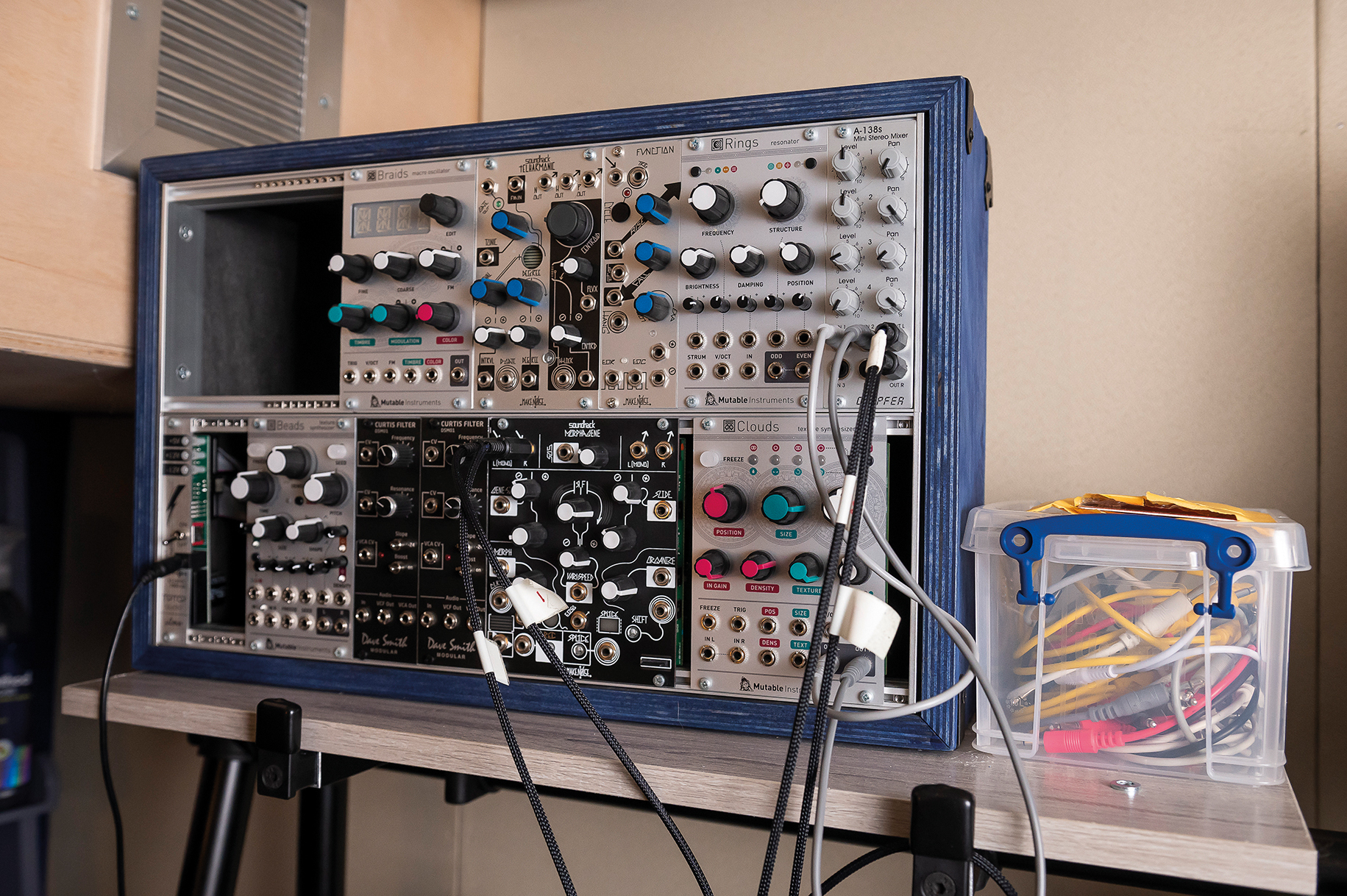

Presumably, your modular setup helps you obtain some of the more modern-sounding effects that you hear on Battery Life?

“As mentioned, when I started making Hall of Mirrors I decided to investigate every piece of electronic gear available, so I thought I’d do modular as well. Like most people who go for modular I didn’t have a clue about all of the CV stuff, but if I can do it anyone can.

“Mutable Instruments’ Clouds has a lovely reverb on it – if I use it to change the pitch and ramp things up an octave it all sounds so granular, lovely and juicy and I’ll tend to have that sitting behind what the piano’s doing. The Make Noise Morphagene is a sampler that also granulates everything, so I’ll use that to add a lot of texture.”

We read that you’re doing a Pitchblack Playback event in support of the album. What does that entail?

“One of the symptoms of the pandemic is that whole swathes of time have disappeared. I heartily agreed to this Pitchblack event thinking I’d be playing live but I’m not. I was quite looking forward to that, but apparently everyone sits in the dark listening to the album, but that’s fine – I’ll just have a nice cup of tea.”

You’re going on a European tour in April. Will you be playing the whole of Battery Life or a mixture of tracks from across your career?

“I’m aspiring to play the whole of Battery Life, mixed with bits of Hall of Mirrors that have stood the test of time and some of the earlier EPs I’ve released. I’ve been rehearsing the set with a much more electronic setup – funnily enough with a digital piano as my fundament, but I’ll be surrounding that with all the synth stuff, a little Elektron Digitakt as my sequencer and a grand piano behind me so I can chop and change depending on my mood.

“My sole aim is to master not having bandmates on stage with me. That’s why I have all these TVs and things that randomly happen to emulate that spontaneity. I’m determined to get it over the line, but it’s still a mission.”

Despite your experience as a player, is playing in front of an audience still scary?

“I’m fine performing in front of a few others but playing in front of an audience makes you lose your mind. You spend the first ten minutes hiding from them and then there’s a crossroad where you get more into yourself but end up becoming so cocksure you become a pain in the arse.

“I’ve been watching a lot of Noel Coward interviews recently about how he dealt with an audience. At one point he was booed badly but his genius way to deal with that was to just stand there and bow continually until they ran out of breath. I admire that level of courage and aspire to it. I can feel what’s happening right at the back of the room, but if someone’s got a cough they need to be silenced because you need complete control.”

Does that control mean limiting the amount of things you take on stage?

“I do try to pare things down as much as possible because then I can rely on my fingers and my history. The more technology there is, the more nervous I am that it might fail because I still feel that same level of naivety as someone who’s only been doing it for five minutes.”

Neil Cowley's Battery Life will be released 24 March on Mote.