Music theory basics: master cadences to develop your chord progressions

The wonderful world of musical punctuation offers near-endless possibilities. Get to grips with them today...

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In musical terms, a cadence is a short phrase, usually a sequence of two chords, that’s used to ‘punctuate’ a chord progression. In the same way that regular punctuation in a text has commas, full stops and semicolons, there are different cadences that are used for different musical purposes.

There are four main varieties of cadence: perfect, imperfect, plagal and deceptive. These all perform different functions, but what they have in common is simple: they’re all used at the end of a musical phrase to signal to the listener that the music has come to a defined point, and that something new is about to happen - either the piece has ended, or it’s about to head off in a new direction.

Music is all about making the listener feel something, and cadences are like prefabricated little building blocks that can be used for exactly that purpose. One cadence may bring a sense of resolution, making you feel satisfied or euphoric, while another may leave you with a feeling of mystery or concern.

A lot of the time, when you’re putting a piece of music together, you’ll be using cadences without actually realising it, as their use is often more instinctive than planned. Even so, consciously popping one in every now and then ensures that your piece is heading where you want it to go.

Here, we’ll give a brief rundown of what makes up the basic form of each cadence, then take a look at one or two practical examples to illustrate how they’re used.

Step 1: To begin, let’s look at harmonising a C major scale: C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C. By stacking up notes at two-step intervals from each note (or degree) of the scale, we make three-note chords, or triads. The first note of the scale is C, so a triad built on the C would be known as a I chord. To make it, we jump two steps between notes, missing out D and F to get C-E-G.

Step 2: If we then give similar Roman numerals to the other notes in the scale, we get the series of chords shown above, from which we can start to assemble cadences. G major is the V chord, for example (G-B-D), while F major is the IV chord (F-A-C). Minor chords are given lower-case numerals, such as the ii chord – D minor in this case – (D-F-A).

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Step 3: The most common form of cadence is a perfect cadence (V-I), formed by placing a V chord (also known as the dominant) immediately before a I chord (tonic). This is the musical equivalent of a full-stop, making it sound like the music has ended. So here we have a perfect cadence - a G major (V) followed by a C major (I).

Step 4: Inverted perfect cadences are also possible. In this example, the V chord (G) is played as a second inversion (D-G-B), while the I chord (C) is played as a first inversion (E-G-C). Arranging the notes like this provides a smooth transition between chords due to the B in the first chord now being adjacent to the C in the second chord - a practice known as voice leading.

Step 5: Our second cadence is the imperfect cadence. This is where the second chord is a V chord, but the first can be almost anything else. In the above example, we use A minor and G major to make a vi-V progression. This is like a musical semicolon, because it sounds unfinished. You can use it in the middle of a phrase to signal the next segment.

Step 6: The third type - the plagal cadence - is made up of a IV chord followed by a I chord, and is another form of final cadence, traditionally used at the end of hymns, hence its alternative name: the ‘Amen’ cadence. Our example shows an F major (IV) followed by a C major (I).

Step 7: Deceptive cadences (aka interrupted cadences) are formed by a V chord followed by any chord other than the I chord. Deceptive cadences always come as something of a surprise, since you’re expecting a I chord after the V chord. They can be used as the musical equivalent of a comma, leading from one part to another.

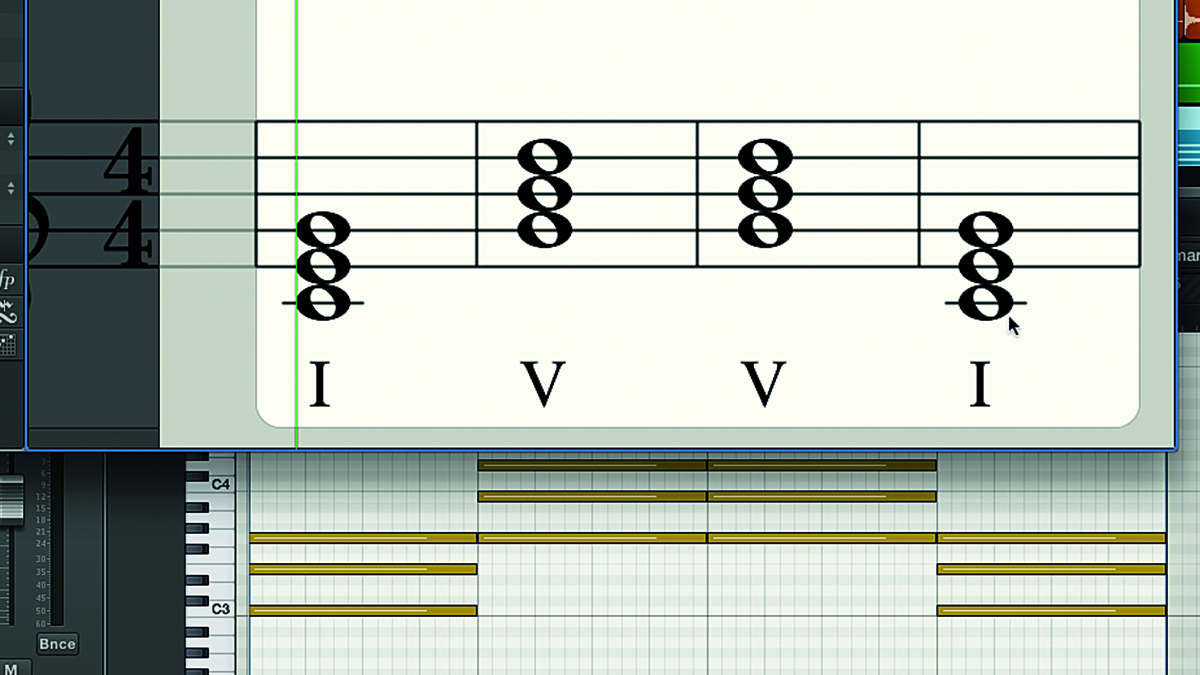

Step 8: Here’s a two-bar section of a track that uses just two chords - a I chord (C major) and a V chord (G major). This first progression from C to G (I-V) is a good example of an imperfect cadence. It feels incomplete, open-ended…

Step 9: …And then we have a section that reverses the progression, giving us G to C, or a perfect cadence (V-I). In contrast with the previous example, this resolves satisfactorily back to the tonic centre (C). What happens when we stick these two phrases together like the clauses of a sentence?

Step 10: Our first, open-ended phrase dovetails neatly onto the second phrase, which rounds things off nicely after the cliffhanger of our imperfect cadence, forming the progression C-G-G-C (I-V-V-I). Using the punctuation analogy, the imperfect cadence in the first half acts like a comma, while the perfect cadence at the end is like a full stop.

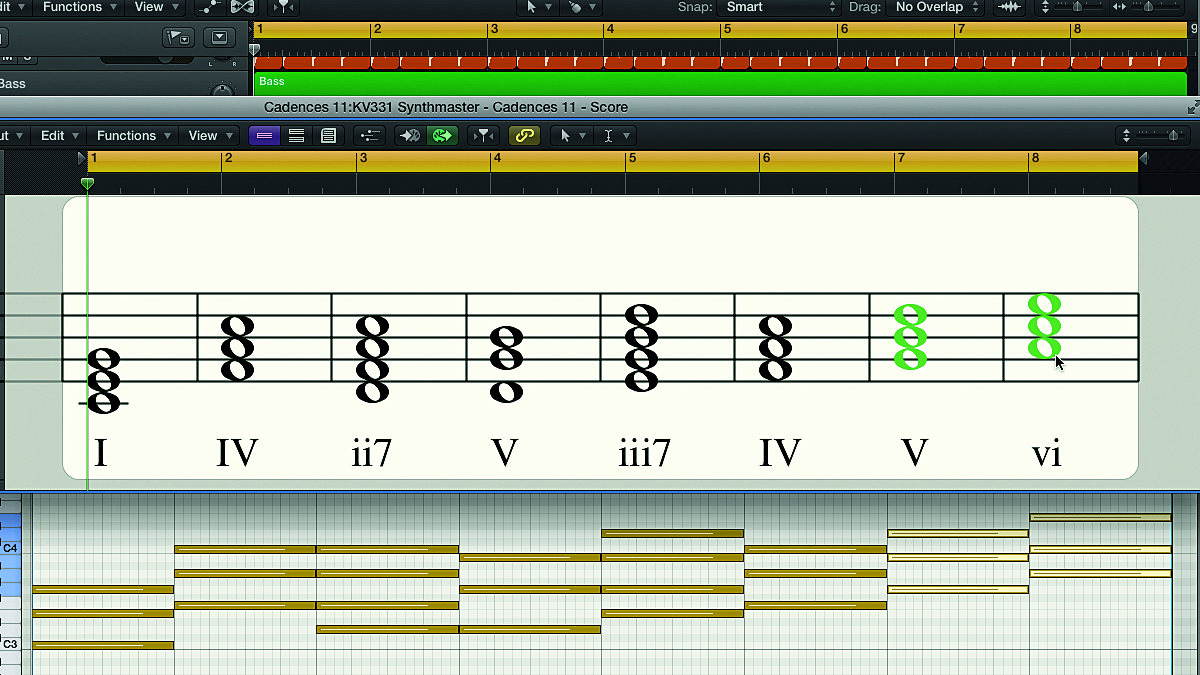

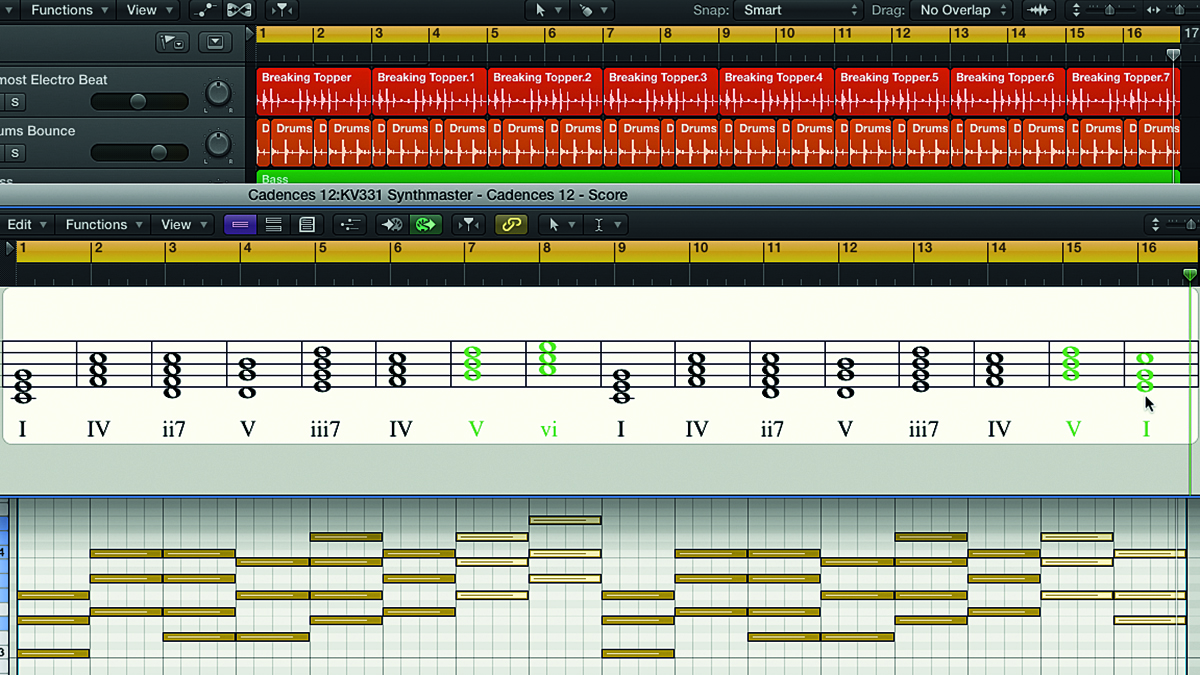

Step 11: Finally, here’s a four-bar progression in C major, using the chords C-F-Dm7-G-Em7-F-G-Am. The last two chords (G-Am) form a deceptive cadence (V-vi) that tricks the ear into expecting a resolution that doesn’t come. We expect to hear a majestic C major, but the A minor we get instead leaves us hanging.

Step 12: Now that we’ve built our audience into a state of anticipation, we repeat the phrase, only this time swapping out the last A minor chord for the expected C major, resolving the progression with a perfect cadence. Playing the first section alone doesn’t sound like a ‘finished’ piece of music, but ending it in this way brings a sense of finality.

Recommended listening

The Beatles, I Will

The Beatles loved a bit of a deceptive cadence every now and then, and towards the end of this classic love song you’ll find the perfect example. Rooted in the key of F, the last line of the last verse cycles around three times, leaving you to expect a resolution on the tonic chord (F major). It continues, however, by delaying our gratification in favour of two bars of a flattened VI chord (Db7) before finally getting around to the F major resolution for the last “I will”.

Nero, Guilt

Halfway through the radio edit of this dubstep cut from 2011, there’s a stonking perfect cadence at around 1:55, just as the drop section concludes and gives way to the subsequent verse. The song is centred around F minor, so the section ends with a iv, V, i (Bbm-C-Fm) progression that provides a very definite transition between the two sections. The perfect example of the perfect cadence doing its job as a musical full stop.

Pro tips

Picardie bunch

Sometimes the final cadence of a phrase in a minor key ends with a major chord instead of the minor you were expecting. This effect is known as a Tierce de Picardie. A good example of this would be Ghosts n Stuff by Deadmau5, in which the main progression is Bbm-Ab-Gb-Eb. If you didn’t already know the song, you might easily expect the last chord to be an Ebm, which works just as well but has a completely different, less distinctive, less dramatic flavour.

Name, set and match

Cadences can be a bit of a confusing topic because there are so many different names for the particular types. For instance, a perfect cadence can also be known as a ‘full close’, ‘closed cadence’, ‘final’ or ‘full’ cadence. An imperfect cadence could also be a ‘half close’, ‘half cadence’, ‘semi’ or ‘incomplete’ cadence. Deceptive cadences are also sometimes known as ‘interrupted’, ‘irregular’, ‘avoided’ or ‘broken’ cadences.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.