MMM: "At some point we get the feeling that we’re not in charge anymore – the track has a life of its own and is suggesting what it wants"

The glowing techno chords of MMM’s long-awaited debut album, On The Edge, are delivered with razor-sharp precision. Danny Turner charts the record’s creation

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Having first met in 1994, Berlin-based duo Erik Wiegand and Michael Fiedler have collaborated intermittently on numerous singles and EPs, producing electro, funk and techno-influenced club music under the name MMM.

Berghain resident and producer Fiedler (aka Fiedel) brings his DJ background to the fore, while Wiegand (aka Errorsmith) lends his experience as a software developer to provide creative solutions.

MMM’s slaying 1997 electro track Donna was an immediate success, yet the duo would not reconvene for over a decade, and it was not until recently that they combined to create their debut album, On The Edge.

Sophisticated and emotionally complex, the album’s refined, meditative tension draws on two decades of techno culture and Wiegand’s in-depth knowledge of Native Instruments’ Reaktor and self-designed additive synthesis software, Razor.

Can you give us a bit of background on your careers prior to working together?

Erik Wiegand: “I was born into a musical family. My father played in a wedding band and had a small home studio, so I was able to use all of his drum computers and multi-track tape recorders. I moved to Berlin in 1991 where I started to take my first steps into production, mostly buying second-hand equipment.”

Michael Fiedler: “We met in 1994 because a friend of ours had a radio show. At that point I was already experimenting with music production and had been DJing for a while too.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Your first release was a bit odd as it comprised techno tracks on the end of an indie rock album…

EW: “I was friends with the bass player of a band called Surrogat and they asked if we would be interested in remixing some tracks from their album, Soul. We thought it would be a good idea for our remixes to be on the album that the original tracks came from, so yes it was unusual but I liked that.”

Your early EPs Elektro Cut and Donna were a bit more electro-based?

MF: “We always like music that has a groove. Erik and I came together because he liked what I was playing in my DJ sets. We were also keen to make electro music rather than the straight, four-on-the-floor techno stuff.”

We’re introverts, so the only promotion we did was to bring the track to the attention of some Berlin-based music publications

EW: “I would definitely make a distinction between the remixes on Surrogat and the MMM records, which were experimental but still thought of as DJ material that could be played out. Elektro Cut is an electro track and Donna is an acid techno/electro track. We always thought we should have a banging track on A1 and get a bit wilder with the others, but they were all designed for the dancefloor.”

What gear were you using back then?

EW: “We were working from my home studio and using the Roland TR-606 and 808 drum computers. I was producing on the Atari and making whole songs on it like you would nowadays on a DAW but recorded to DAT.

"When I started working with Michael on MMM, we switched to a different approach where the drum machines were running and we’d jam by changing the sounds, hitting mute and pressing the break button on the 808. We recorded whole jams on DAT and then I’d put the recordings into the computer and cut the best bits together to make it more condensed.”

The track Donna was a big seller, but you didn’t seem interested in capitalising on that. In fact, you didn’t work together for another decade?

MF: “We didn’t realise Donna had been successful for quite a while. We had no distributor, so I’d just take vinyl copies of it to record stores, play it to the guys there and maybe sell three or four copies. It became successful bit by bit, but Erik was starting to work with Native Instruments at this point and we had different directions of interest. When he started his Errorsmith project, he began experimenting with analogue and digital sounds and we felt we could work together again.”

EW: “We’re introverts, so the only promotion we did was to bring the track to the attention of some Berlin-based music publications. Although Donna sold a lot, our telephone wasn’t ringing with lots of promoters wanting to book us, and by the time we started making music again everything had changed and people were not buying vinyl anymore.”

We keep hearing that vinyl sales are growing exponentially. Do you see evidence of that?

MF: “No, not at all. As a DJ, I still buy vinyl and like to play it, but sales are more common in represses for the big pop artists or rock bands, and that scene is for collectors not DJs. Most of the records I buy or make with my label are for DJs to play out, but not too many of them buy records anymore, which is a little bit sad.

"It’s very convenient to carry a USB stick, but I still like the feeling of vinyl so I’ll do it where I can, but it’s difficult to find venues these days that provide a DJ setup without broken needles and tone arms.”

I had an idea for an additive synthesiser and convinced them to make it. That synth was called Razor

After 25 years of releasing singles and EPs, why was now the right time to record your debut album, On The Edge?

EW: “It came to us very naturally because we were working on new tracks that had a similar vibe to them due to the fact that we were using mellow chord sounds as a basis. These were not banging tracks that would suggest themselves for a single or EP and we wanted to explore that style further. In the end we thought we had enough ideas and material for an LP and were interested to see what people would think.”

MF: “We called it On The Edge because the album is a bit melancholy and meditative but there’s also a lot of tension. We want the music to feel like you’re exploring and expecting something to happen but it doesn’t happen, as if the mood is suspended and about to push you over into something.”

Erik, you’re more than a musician but also a software developer. When did your interest in this field emerge?

EW: “At the beginning of the ’90s I started opening up analogue synths and modifying them. I read everything I could find about synthesis, studied computer science and got increasingly into this topic.

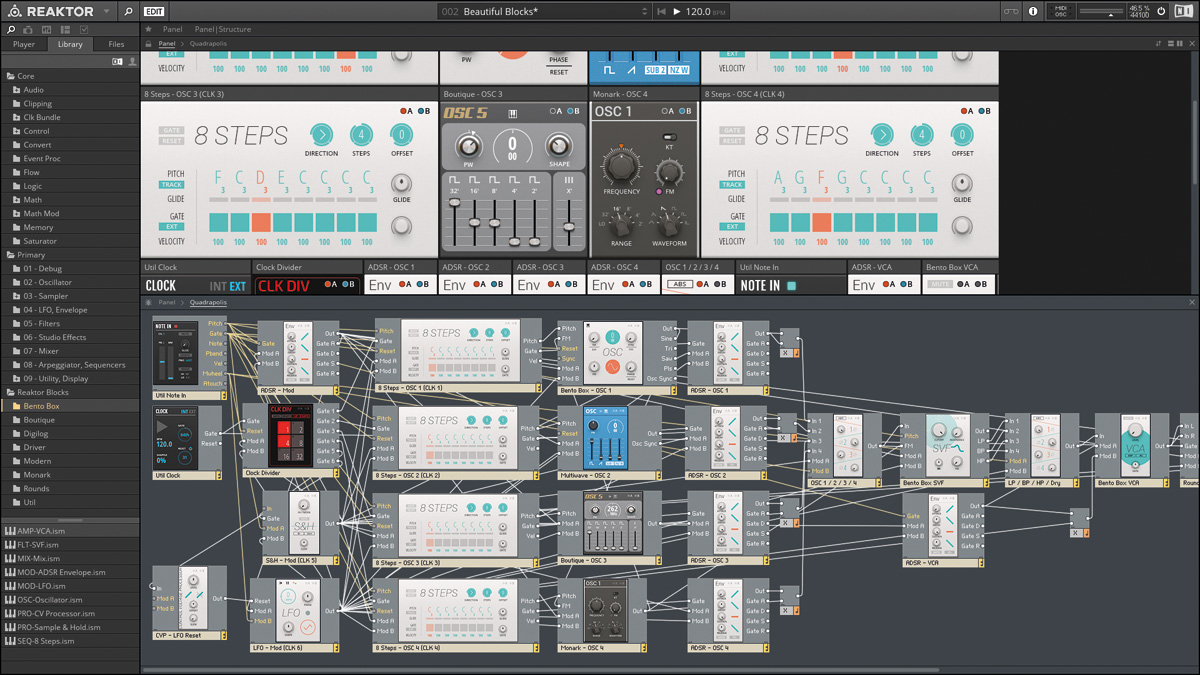

"I started to use Native Instruments’ Reaktor very early in 1998 and thought it was mind-blowing because it was similar to programming but in a graphical way, which enabled me to focus more on the synthesis aspect rather than coding with text. From then, I started to develop my own Reaktor instruments for Errorsmith and our productions with MMM.”

Were you working for Native Instruments at this point?

EW: “I started working for Native Instruments as a head of beta testing when it was a small company. In 2004, I started contributing to the Reaktor library and organising contributions from external Reaktor developers.

"At the time, it was possible for NI to sell Reaktor instruments as a separate product without people needing to own the software, so I had an idea for an additive synthesiser and convinced them to make it. That synth was called Razor and came out in 2011. Besides music-making, I still spend a lot of time developing Reaktor content for my own music and Native Instruments.”

Do you have any examples of Reaktor instruments you have made to help with your creative workflow?

EW: “At one point, no synth on the market was exploring the idea of recreating traditional features like filters, oscillator shapes and effects in an additive way using lots of sine wave oscillators to emulate them. I tried it out on Reaktor and it sounded really good.

It was deliberate to leave the music sounding sparse and restrained. It seems like everything is screaming at you these days

"Another idea I had was that people often reverse sound recordings and I thought I could patch something in Reaktor so that when I pressed a button it would reverse what was just played. If you listen to my first Errorsmith record in 1999, you will hear these reversed parts, which were all made by jamming on-the-fly.”

Michael, do you also have an interest in software design?

MF: “Not as much as Eric, he is the driving force of the project when it comes to sound-shaping. On the album we used a lot of his creations and whenever we face problems he typically finds a solution in Reaktor to solve it. I like to get my ideas out quite fast and I’ll dig into all of the plugins, but I’m not into deep-learning how a synthesiser works. I love Razor – it’s a really nice tool, but I’m more of a user than a creator.”

Is it true that you’re both anti-sample, in that you prefer sounds to evolve rather than remain static?

EW: “As Errorsmith, I put restrictions on my music and only use synths that I’ve built myself, but with MMM we use whatever fits. If we find a sample that suits the track, we’ll use it, but I prefer to keep synthesiser elements the way they are rather than freezing the sequence because I feel they sound better that way and you can always go back to the knob settings if you want to adapt something.

"We also enjoy presenting the material live, so it makes sense to keep to the original synth sound. With On The Edge, we used two external hardware synths and made static recordings, but when it came to the live set I recreated those sounds using Reaktor just so I could change tempos and avoid some of the warping issues that you sometimes get with samples.”

In practical terms, how did you work together on this collection on tracks?

MF: “We always work in person and as I was not travelling around much due to the pandemic we were able to spend more time together. In the past, Erik would prepare stuff and invite me to think about it and jam with him. If he has a technical solution for an effect, he will develop that in Reaktor and then we’ll decide whether it’s worth adopting.”

EW: “For us, it doesn’t make sense to send a project back and forth and it’s important to have that social interaction. We’re very close friends and during the pandemic Michael was almost the only social contact I had.”

What tools did you jam with to kickstart your ideas?

EW: “I always have a collection of demo sounds from Reaktor patches that I’ve created, so we started with a basic mellow chord sound that would be interesting enough to define a mood and play a role throughout the entire track.

"It’s rare that we know what our end goal is; we just go step by step, adding more and more before we start to refine and refine. It’s a very organic process and at some point we usually have the feeling that we’re not in charge anymore – as if the track has a life of its own and is suggesting what it wants.

"When I work alone, it seems more difficult to do that, but with Michael it seems easier to pinpoint the direction we should go in.”

By refining the music, the sound becomes more spacious and the chords have room to come alive

Are all your ideas sourced from Reaktor software?

EW: “I bought a Teenage Engineering PO-20 Arcade Pocket Operator, which is really nice because every chord is based on an 8-bit arpeggiator. The track Everything Falls Into Place was made almost entirely on the PO-20, but we’ll quite often use Ableton’s Operator to give us a saw tooth sound and Ableton’s Auto Filter, which has these analogue-modelled distortion/filter types. We find that those are very nice for distorting chords because they sound very rough and add interesting non-harmonic overtones.

"The only exception to the rule was the track Farsta Dream, which evolved from a beat first and then we wanted to incorporate a chord, so I made a Razor patch that allows you to create pitched noises. If you listen to the track, the snare sounds like a snare and has a noisy tale to it, but it’s actually a snare rattle made out of a chord.”

Your sound is very reductive, so much so that some tracks only contain four elements…

MF: “Previously, our tracks were based on DJ material so we didn’t pay so much attention to those spacious elements, but in the process of making these tracks we decided to eliminate sounds to give everything space to breathe. When you have a busy track, you cannot always hear objects and start to realise that certain sounds are not needed. By refining the music, the sound becomes more spacious and the chords have room to come alive.”

EW: “It was deliberate to leave the music sounding sparse and restrained. That was very new for us and we found it interesting, particularly as it seems like everything is screaming at you these days. We spent a lot of time finding the right reverbs, which fill the space of course, but it’s not wishy washy.

"On Farsta Dream, we put a feedback delay onto a reverb that swells up and down, giving tension to the track. We also put a Barber pole Phaser from the Reaktor user library on the reverb tail so you have the feeling that the notches and peaks of the phaser are going up all the time. It’s an illusion but it fits the meditative feel of the track very well.”

Your beats are equally sparse – the tracks often sound like they’re hanging from a thread. Is that part of the tension you want to transmit?

EW: “The beats are reduced to the core. I wouldn’t say the patterns are experimental, they’re quite basic and nothing you haven’t heard before, but what’s strong about the album is the atmosphere it conveys rather than how intricate the rhythms are, especially compared to other footwork artists.”

MF: “As a DJ, when I buy music it has to be groovy, even if it’s techno or sparse-sounding. The track On The Edge has a straight bass drum with one variation and the timing of the clap is quite dubstep, but when all the elements come together you have a groove that you can almost float on. If the beats were too linear, it wouldn’t sound like MMM.”

EW: “We premiered the album at the Unsound Festival in Krakow, which was very nice. We played the uplifting stuff that we’re best known for at a house tempo and that contrasted well with the new tracks where everything slows down and gives a certain weightless effect. After the show, people told us that this was a really cool feeling for them.”

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.