Joe Satriani talks Surfing With The Alien track-by-track

The gear and technique secrets behind a shred guitar masterpiece

Still riding the wave

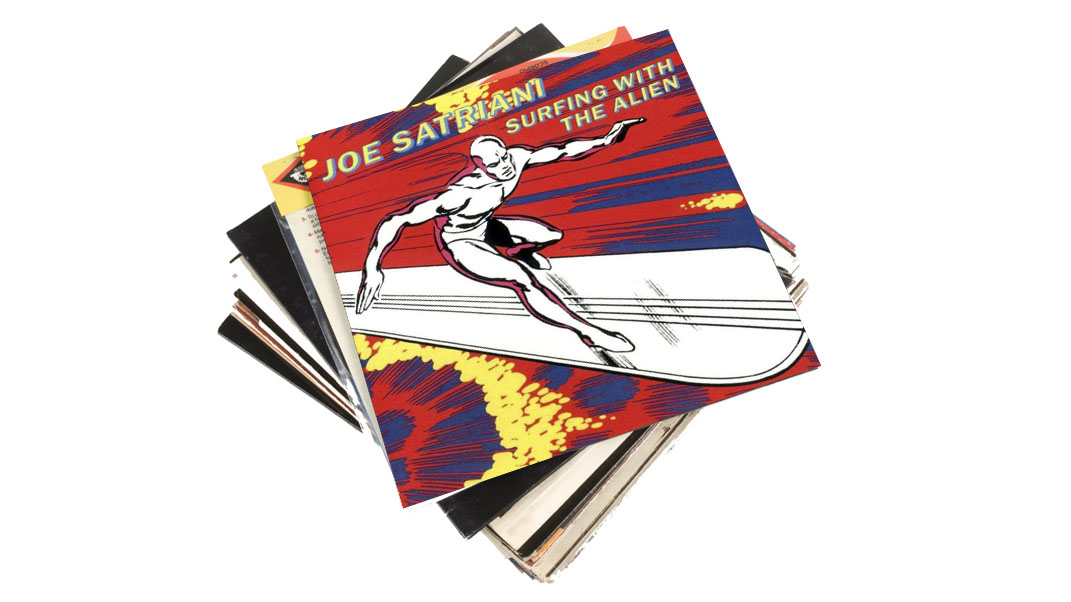

Joe Satriani is known for many things: his inimitable legato technique, formidable guitar tutelage legacy, uncompromising approach to composition, those shades. But most of all, it’s 10 tracks and four words that both defined Satriani and shred guitar as a whole: Surfing With The Alien.

Now celebrating its 30th anniversary, Surfing stands as a landmark release in instrumental guitar music, fusing Joe’s love of guitar players right across the spectrum with a sense of fun, technique and, crucially, melody - the resultant album spanned high-octane blues fusion (Satch Boogie), lyrical ballads (Always With Me, Always With You) and bombastic rock (Ice 9), with consistently thrilling results.

The idea for the album was to celebrate everything that I really liked about electric guitar

“Globally, the idea for the album was to celebrate everything that I really liked about electric guitar, my roots, and the players that I still really like,” Joe explains.

“And, so, for me, it went from Chuck Berry to Hendrix, from Wes Montgomery to Allan Holdsworth, I wanted to celebrate all of it. I was a kid that grew up listening to The Beatles, and The Stones, and Jimmy Page, and Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, and I wanted all of that in there. But at the same time, a large part of my playing is Tony Iommi and Billy Gibbons. I'm just a sum total of all of the guitar players that I think were really cool. And I wanted to make an album that was about that.

“I pitched the album to Relativity Records' president, Barry Kobrin, in the exact same way. And he looked at me funny because it was such an untrendy thing to do, but he said, ‘Well, okay.’ He'd heard me play Satch Boogie at a club in New York City one night and so he said, ‘Okay, is the album going to be like that?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, pretty much, with a couple of left turns here and there.’”

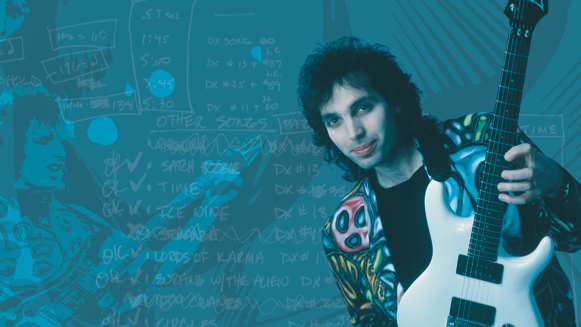

Satriani’s second release on Relativity Records, Surfing was recorded on a miniscule-for-1987 budget of $13,000 at San Francisco’s Hyde Street Studios, which placed supreme pressures on Joe and producer John Cuniberti, but only served to stretch their creativity to the limit as they sought to make the record in Joe’s head using the limited resources available to them.

“It was made with a complete unselfconscious love of the things that I wanted to celebrate on guitar, and it was also made under enormous duress and the feeling that no-one would ever really listen to it and I would be run out of town as soon as I delivered the album,” Joe muses.

“It was under such a climate that it didn't seem that anyone was going to accept such an album. So it was such a wonderful surprise when it was embraced, because it wasn't a calculated record and much was sacrificed to get it done.”

Given the strained conditions in which the album was recorded, what’s perhaps most remarkable is just how much Joe remembers: his memory is as precise as his pentatonic runs, and the sheer amount of detail he’s able to divulge is more than most artists are able to share about an album recorded last month, let alone 30 years ago.

Kramer vs Kramer

This ability to recall is testament to a true labour of love, particularly with regard to gear. Long before he secured his JS signature models with Ibanez, Satriani armed himself with whatever guitars he could afford - even if that meant sacrificing tuning stability for the sake of functionality.

“For that particular record, I had two Kramer guitars. They were both Pacers and one was the white one that I had purchased in '84 or '82, and it was put together from parts at the Guitar Center,” he recalls.

I'm just grateful that companies make guitars and they sell them for cheap for people don't have a lot of money. That's who I was at the time, and, so, it helped me out at a time when I needed it

“I bought it only because it had a first-generation Floyd Rose with no fine-tuners, and I was shunning that whole idea during the early '80s: I was a no wah-wah, no-vibrato bar kind of thing. But I picked it up anyway and eventually I realised that the thing was really great if you wanted to play out of tune all the time. [laughs] The guitar itself was always falling apart and [guitar tech] Gary Brawer was continually trying to fix it.

“But I had a connection with it, and that became the guitar that I used for my first EP and Not Of This Earth, and then Surfing. And by then I had purchased a second version of that Pacer that had just three single-coil pickups; it was even worse than the two-humbucker version that I had.

“It got limited use in the studio, and after the record was finished, the guitar was never used again. I still have it, but I don't know what to do with it. It's such a poorly constructed guitar, but it was inexpensive and I'm just grateful that companies do that. They make guitars and they sell them for cheap for people don't have a lot of money. That's who I was at the time, and, so, it helped me out at a time when I needed it.”

Where he couldn’t afford more instruments, Joe also took some more innovative approaches to tone-seeking, using his so-called Boogie Body Strat.

“I also had a guitar that I had put together from parts. It was a Boogie Body Strat body made out of hard-rock maple. It was an ESP neck that was '59 vintage style, 7.5 radius, ebony fretboard neck.

I'd take the strings off, unscrew the pickguard, put in a new pickguard with the Strat pickups, screw it and string it up, and then do that part

“I worked at a vintage guitar store and the owner had ties with a lot of Japanese manufacturers and US manufacturers that were beginning to pop up. So I was ordering parts and screwing them together and contacting local luthiers to finish and do frets and things, and I had put together two guitars, a red one and a black one. The red one I eventually sold, but the black one is the guitar that I wound up using a lot.

“It was a hardtail, so if I didn't need the whammy bar I'd use that guitar: clean, funky, bluesy. I still have that guitar today. It's on every record doing something. It's an odd-sounding guitar because of the wood, and what I did was I had Gary Brawer make me two or three different pickguards that were preloaded with different kinds of pickups.

“So for the ‘humbuckers in the Strat body’ sound I had a black pickguard with two Seymour Duncan pickups in it. It was a ’59 in the neck and a JB in the bridge, and I would screw that one in when I needed that kind of a sound, and then when I needed to do really Stratty kind of sounds, I would tell John Cuniberti to take a break, I'd take the strings off, unscrew the pickguard, put in a new pickguard with the Strat pickups, screw it and string it up, and then do that part. That's basically because I couldn't afford to have all these different guitars; I just had three guitars and a bunch of pickguards. The poor man's guitar arsenal!”

It’s these details and more that Joe intends to expand upon at 2017’s G4 Experience held 24-28 July at Asilomar Center in Carmel, CA. The guitar camp celebrates Surfing’s 30th anniversary, bringing all the album’s major players back together to answer any possible question about any aspect of the recording - and judging from Joe’s recollections, we’re inclined to believe they’ll have the answers.

“The G4 Experience this time around is going to try to explain, as well as detail and celebrate, all those moving parts to the creation of the record,” Joe enthuses. “The recording of it, the fingertips, the picks, the strings, the amps, the performing of it, how it morphed, how it changed, and how each of the new people, players, that came along to help celebrate it elevated the songs even more each time we went out with them.

“The album wouldn't have broken through if it wasn't for these other these very important moving parts. Obviously, me and the guys, John Cuniberti, and the musicians, Jeff Campitelli and Bongo Bob Smith, making the record, but also Stuart Hamm and Jonathan Mover that came on after the record was done, became new friends and comrades, and actually championed the record in a totally different style on tour.”

Power trio

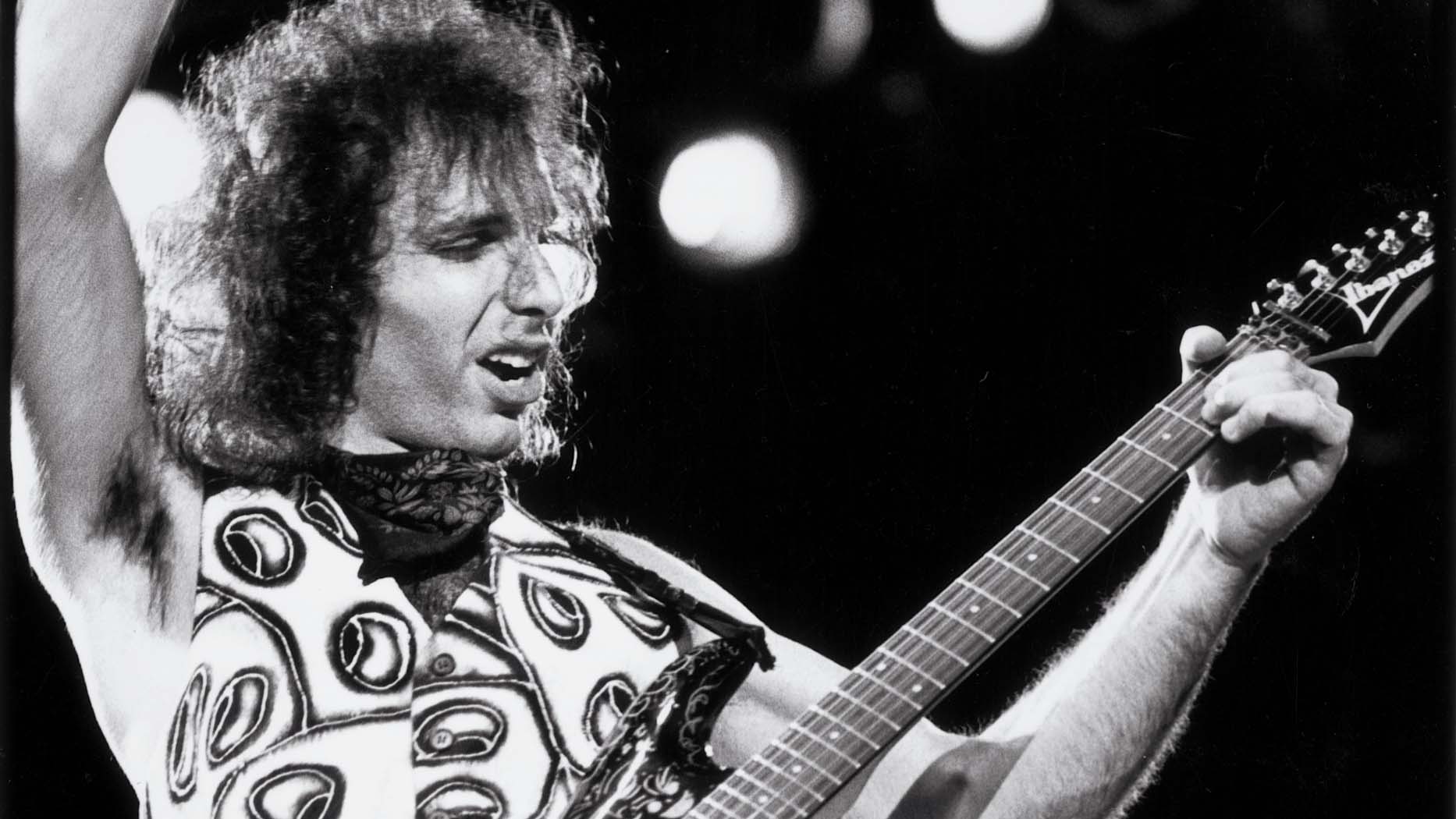

For longtime Satch fans, the most exciting aspect of this year’s G4 Experience is that it reunites the original Satriani band line-up, bringing bassist Stu Hamm and drummer Jonathan Mover back to the fold.

While Hamm was onboard for Satriani’s 2008 Professor Satchafunkilus And The Musterion Of Rock tour, Joe hasn’t performed with Mover since the mid-’90s - their reconnection was a curious series of events…

“We ended on a bad note. There were some just touring business stuff that pissed the two of us off and so we decided to just call it quits,” Joe reflects. “And that goes way back: that tour ended the night of my 40th birthday.”

“Fast-forward to a few years ago and I'm doing a TV show, and a drummer, Robin DiMaggio, was the musical director, and we started an interesting collaboration where we wanted to create a song that would send a message of love and hope around the world and unite people. And that became a song called Music Without Words.

“Robin is the musical director for the UN, and one day when we were talking about musical things, he mentioned that he had spoken to Jonathan Mover, and I went, ‘Oh yeah, Jonathan, we had such great times, fantastic touring experiences,’ and everything. And I said, ‘I haven't talked to the guy in 20 years,’ and Robin just said, ‘You know, you should talk to that guy.’

“So, he sent me his number and I just called him and I said, ‘This is the weirdest thing, isn't it? I'm calling you out of the blue. I have nothing to talk about other than, ‘Hi, isn't it weird that we didn't talk for 20 years?’’”

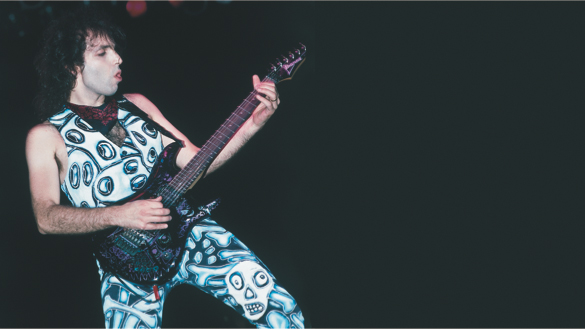

The original power trio were famed for their energy and ferocity, which paired virtuosity with showmanship to unpredictable and virtuosic effect. But as Joe points out, their origins were anything but orthodox.

“In the summer of '87, Surfing With The Alien was about three months away from being released, and I flew out to Bensalem, Pennsylvania to go to the Hoshino USA factory to meet the Ibanez guys and talk about a JS model.

“On the way there I found out that Jeff Campitelli was not interested in going touring with this weird idea of me going on tour as an instrumentalist. So I arrived in Philadelphia, I know that the guys at Ibanez want me to play at the summer NAMM show that's happening in Chicago a week from then. So I've got seven days or six days and I've got to put a band together.

“So I'm sitting in the office just waiting to meet the guys from Ibanez and there's this other guy there and he looks pretty cool, looks like a young musician. So we're like, ‘Hi, how ya doing, I'm Joe.’ ‘I'm Jonathan.’ ‘What are you here for?’ And he says, ‘Yeah, I'm a drummer. I'm here just to talk to Tama.’

“I had a cassette of this new album called Surfing With The Alien, and I said, ‘Hey, what are you doing next week?’ And he said, ‘I don't know. I might go to the NAMM show.’ I said, ‘Would you play with me, if I gave you a tape, would you learn a couple of songs and we'll just play? There's this guy, Stuart Hamm, I've never played with him but my friend Steve Vai said he's a good bass player - would you do it?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, sure, I'll do it’.’

“So I gave him the cassette and I shook his hand, I said, ‘Okay, see you later, see you in Chicago.’ And a week later, for the very first time, Stu, Jonathan and I stood on stage at The Limelight in Chicago, and we tried to get to know each other during soundchecks. We pulled off the gig.”

The great beyond

Those unable to make it out to the Asilomar Center will be keen to know whether Joe intends to take the band out on tour, but his plans for 2017 are still very much TBC.

“I'm up in the air about that. I'm very focused on preparing for the last run of dates to support the Shockwave Supernova record. It has crossed my mind that I'm going to have to start thinking about the next touring band, but that's way in the future.

“Every year that I go out on tour I think about all the craziest ideas that would be great to go out with and I think, ‘I should see if Jeff Beck wants to join my band for a month or something.’ I always think of the craziest idea first and then work backwards, because you never know, that person that you think would never return your call might be sitting at home with nothing to do.”

I've never actually called Jeff Beck and asked him to join the band, but that doesn't mean I won't at some point

“But having said that, I've never actually called Jeff Beck and asked him to join the band, but that doesn't mean I won't at some point. I really don't think he's going to say yes ever, but, you know. It doesn't hurt in trying or dreaming, right?”

Of course, it was Surfing that introduced Satriani to the world and allows the guitarist to entertain such ideas today, but it was its strong sense of composition and melody that ensured it stood the test of time and influenced generations of guitar players to come.

Here, Joe takes us on a journey through the brainwaves that led to the composition of each of the album’s 10 tracks, the recording process that played such a crucial role in defining the sound and feel of the record and how his perception of the songs have changed over the three decades that have passed. Surf’s up…

Joe Satriani’s G4 Experience: Surfing With The Alien 30th Anniversary is held on 24-28 July at Asilomar Center in Carmel, CA. Packages are available from the camp’s official site.

Don't Miss

Joe Satriani's top 5 tips for guitarists

1. Surfing With The Alien

“First of all, the title track was not the title track; it was just a track on the record but it started off pretty innocently. And the song was a bit longer, actually: there was a second part. There was a part that was like a pre-chorus section that at the very last minute John and I decided to get rid of. It was a good decision because I think it focused more on the fun aspect of the song.

“I was using that Black Boogie Strat into a very early Chandler Tube Driver. I had three or four of them at the time, and I would go right into an early-'70s Marshall 100-watt head, into a 4x12, and that's how we pretty much did that particular song. And we just made adjustments to the amount of distortion that was generated from the Chandler Tube Driver.

I hadn't plugged in a wah-wah pedal in five or six years. And I'm leaving my apartment and I'm looking around like, ‘Shall I bring something else?’

“When we went to do the melody, there's a funny story with that. We were looking for a sound, and the day that I was leaving to go into the studio, I hadn't plugged in a wah-wah pedal in five or six years. And I'm leaving my apartment and I'm looking around like, ‘Shall I bring something else?’ And there's the dusty wah-wah pedal in the corner and I just looked at it and I thought, ‘Maybe I should bring that. Maybe that's what I need.’

“I got to the studio, I remember I said, ‘I've got this wah-wah pedal.’ And John looked at me like, ‘You haven't played a wah-wah pedal since I've known you.’ But I said, ‘Well, let's just try it.’ So I plugged that into the Tube Driver and that's going into the Marshall, and then we said, ‘We need something else.’ So he goes, ‘Well, we've got this Eventide 949 [Harmonizer] here.’ And John dials up that weird stereo sound where it was like a straight signal on the left and I think on the right it was like minus 11 cents or something like that.

“We had 20 minutes left of the session that afternoon at Studio C in Hyde Street, and we were so excited with the sound, we did this one big pass from the beginning all the way to the end while people were standing at the door, the client with their arms folded looking at us like, ‘Stop playing guitar and get out of our studio. We've got four o'clock.’

“Then we had to break down entirely, which means strip the amps, the microphones, everything. So the sound was lost. The next time we were in the studio a couple of days later, we bring it up and we go, ‘Wow, that's really good, but the guitar's not really in tune.’ And then we go, ‘Well, maybe we can just fix it.’ But we couldn't because there was no way to get the sound back. So that became that sound for the song.

“And then we just did the solos. The solos are all separate sounds for all the different keys, but we got really lucky there. I mean, it was just one of those moments where you just have to do it. There was no extra time, there were no do-overs, there was no auto-tune. That's what we recorded to tape that afternoon, and that's what we're going with. It had a lot of fun and a lot of drama, and we were so excited about how cool it sounded. And yes, you get to hear the Kramer with its shifting pitch centre in all its glory!”

2. Ice 9

“The song was about a little slice of an idea from a Kurt Vonnegut book called Cat's Cradle, and it was about a chemical that was devised by military scientists to turn water into ice so that armies could traverse muddy areas and, of course, it all goes wrong. So I was just thinking about something so insidious and cold and hoping of things tightening up and becoming ice. So this was my description to all of the players, when presenting the idea to John and to Bongo Bob who was doing the final [drum] programming for me.

“And I should say that the idea behind the record was let me record to a drum machine first so that I can get my ideas together and then bring in a drummer, which was Jeff Campitelli. But very quickly we realised that I had played in a very strange way: I was swinging around this metronomic drum machine and there was no way to go back and change it. We didn't have the money to go back and redo the parts once Jeff had played his part.

“But once Jeff went in and he started playing groovy drums, it only made sense with Satch Boogie, because it was a boogie and everyone thought he was swinging. But the other song, it appeared that the charm was that I was playing with machines; it was like Joe was the robot, you know what I mean? There was a characteristic to the music that was lost once all the machines were replaced, and John and I missed that awkward charm, I suppose you might say.

We were not only enamoured artistically with the idea of using drum machines, but we were also charmed with how much money it would save us, because we had so little to record the album

“Ice 9 was one of those songs that it really helped by being obviously a mechanical drum kit, and you have to remember that this is the '80s, so we were enamoured with the idea that the promise of what Kraftwerk was working on, in earlier times, was actually coming to fruition. And, so, we were not only enamoured artistically with the idea of using these machines with really loose guitar playing, but we were also charmed with how much money it would save us, because we had so little money to record the album.

“The budget was $13,000, that's what they gave me to record the entire record. It was ridiculous, and, so, there was no way to spend two weeks doing drums, even a week doing drums. So, we quickly shifted gears, and Jeff and Bongo worked out a thing where Bongo would program the drums and Jeff would go in and replace some of the cymbals or all of the cymbals, maybe he would do only the toms or only the snare. As a matter of fact, I think the only thing that's on here that's Jeff are the crash cymbals.

“On that one, I'm using a Boss DS-1 and the overdrive, OD-1, I think. I'm playing my ’60s P-Bass, but I think that's where the rhythm guitars are the DS-1, so they're a bit crunchier. For the solos, I believe it's a Rockman [headphone amp], and we just used one channel of the Rockman and put it up on the middle, flat and dry. I mean, that's about as dry as I've ever recorded. Simple legato technique and just crazy all over the place.

“There's a fun story about that backwards part. We were recording a solo on a Tuesday, and then two weeks later the next solo would be recorded in another room. A month-and-a-half later, the only thing left to do on that song was to record the backwards solo, and we got kicked out of Studio C because we had spent too much time there, but we needed to do the solos. So I asked, ‘Well, where can we go?’ And someone said, ‘You know, D down the hall is open for a half-hour. You guys go in there; you can have that.’

“So we packed up everything, we moved down the hall, we didn't have an amp, we didn't have microphones. I had this little Gorilla amp which was a practice amp and which no-one in their right mind would ever record with, but it was there. And I think I had it for just practising parts in the hallway. So we put that in the music room, and we didn't have a microphone, and so in Studio D there was this funky little talkback microphone that looked like it came from a radio studio 40 years earlier, so I said, ‘Can we use that?’

“So we took that, we unwired it, we hooked it up to my cable, we put it up against this little Gorilla amp which had a six-inch speaker in it, we turned everything up all the way, and then the Atari machine that we had had the ability to record in reverse without having to flip the tape over, which was a big deal back then. So that made it really easy for us because we didn't have a lot of time to be flipping tape back and forwards. I think it took 10 minutes just to get the sound and to record that thing, and we listened back to it and were like, ‘Okay, that's done!’”

3. Crushing Day

“I never should have written that solo! That was some alter-ego thing where I thought it would be a really cool thing to do. I mean, I loved the idea of sweep picking, and that was one of the very first things that I recorded for Relativity when I was trying to sell the idea to Barry Kobrin at the record label.

“This song definitely, out of all of them, echoed the time. It had that early-’80s metal sound to it and strictness. It had more Rockman on it than it should have had, and it had tuning issues because it was done as a demo. And then by the time we decided to put it on the album, we had run out of money and so we didn't have time to replace parts again.

“If we move on from all the issues - which is what I think about very often when I'm sitting here in the studio talking - the thing that I liked about the song was the fact that it was super-melodic and that was the point in creating the song itself. It was really about when we have days that really suck and you feel like the weight of the world is crashing down on you and, so, that's why the title was Crushing Day. You've been crushed down all day.

“But very often I notice that a lot of metal music is focused on riffs, and I thought, ‘Well, I've got a really cool riff, but I think, really, there's not enough wailing going on.’ And, so, because of the guitar instrumental, a lot of that weight that you're trying to describe has got to be turned into some kind of real screaming emotional melody. And, so, my writing approach was to create a super melody and then to have it be harmonised in a beautiful way. And, so, that was really the focus of the song.

We're just going to do what we want to do. There's nobody here to tell us we can't turn the guitar up or we can't have a 382-bar guitar solo!

“The solo section is really long, and I have to say that part of that is that I was so frustrated as a struggling session player that I was always told to stop playing, like, ‘No, don't use that. No, don't make those noises. No, you're playing too many notes. You can't use that technique. No sweep picking. Play more like that other thing, this guy.’ And going into the solo record both John and I were like, ‘Hey, we're just going to do what we want to do. There's nobody here to tell us we can't turn the guitar up or we can't have a 382-bar guitar solo!’

“So I think Crushing Day epitomises the idea that this guitar solo's going to be really long, and so I thought, ‘I'd better work some of this shit out.’ All the other ones are improvised, but this one was too long to just sit there and fiddle about. But, in retrospect, I regret it, because I've always found that when you're on stage and you're playing night after night, that sticking to the script is one of the things that will kill you in the end: it's a solo killer.

“But this particular song, what we found out touring through Jonathan and myself, was that this thing fell apart unless you played it exactly like the record. Of all the songs that I’ve recorded in my whole career, that is the one that is a nemesis, not really because of the technique involved, but it's just that there's something about the strictness of the recording that adds to the charm factor that when you try to redo it, upgrade it, modernise it, humanise it, that it loses its thing. And, so, it's been a nice challenge over the years.

“I have to tell you a funny story now. It was one of the G3 tours and we came through San Francisco, and I remember thinking that I really wanted to play that song. And, so, we had rehearsed it and we had played it, and I remember Jeff scratching his head with me every night going, ‘What is wrong with that song?’ We tried everything. We would liven it up, we would mess it up, we would play it perfectly, we just couldn't figure out what it was.

Steve Vai really loved the record, but I remember when it came to talking about that song, he just said, ‘Yes, it's a really cool song... solo's kind of worked out, though, isn't it?’

“Anyway, we're playing in San Francisco, we play that song, the show goes fine, but in my mind I know I've totally blown it. It's just something about it, I don't know what it is, I played all the notes and everything. I just remember getting a note from a fan, after that show, where he said, ‘What happened to Crushing Day? You messed up every part.’ And it illustrated to me that it wasn't just me that had a problem with the song, that even a fan felt that it was necessary to say, ‘Look, all due respect, Joe, I love you, but what's up with that song?’

“The other funny thing that should have tipped me off years ago was when I finished the record, I remember playing it to Steve Vai. Steve really loved the record, but I remember when it came to talking about that song, he just said, ‘Yes, it's a really cool song... solo's kind of worked out, though, isn't it?’ And it was that little comment between friends that was very telling, because I knew that out of everybody, he knows everything: when he listens to me play, he knows the backstory, just because he knows me.

“We've been with each other since we were kids, but he canned it right away. He noticed that there was something fishy about it. And what I should have known when he said that was that was going to haunt me for the rest of my career! So I'm certain that if I have to play that song live again, that I'll have to come to grips with that.”

4. Always With Me, Always With You

“That song was a basic love song. I had a moment when I was writing in my apartment for the record where I was saying that I should not be afraid of the power and the beauty of major keys. And that year after year I hear people using I IV V progressions, I VI IV V progressions, and the musos will always roll their eyes because they're looking for cluster chords and unusual time signatures and challenging things.

They're not getting together 100,000 people at a time to sing something in 17/8 that traverses four different key signatures

“But if you walk around in the real world you think, ‘Wow’. I went to a stadium and there were 100,000 people singing the song that had three chords in it, and you go, ‘This is humanity. This is people coming together, being united by a simple melody over a simple chord, that hits to the core of their very being.’ They're not getting together 100,000 people at a time to sing something in 17/8 that traverses four different key signatures, you know what I mean?

“Part of me is just Chuck Berry, and I love the simplicity and the power behind getting three chords right and not throwing in 17 other chords when they're really unnecessary. So, these are ideas that germinate within inside of me for weeks, and then I get overwhelmed with a simple feeling and it propels me to be simple and direct and write just the essential notes.

“And then I'll spend weeks, months sometimes, just figuring out which notes to cut out, and that song is a good example of how I was thinking, ‘Well, how did Beethoven do it? How did he get these beautiful melodies to work on top of arpeggios? Can I have these cluster chords? Can I do the I IV V progression when every chord has a three and a four or a six and a seven in it?’

“So I did apply some muso stuff to it. Some late-1800s music ideas to some earlier classical structures and then just tried to play something that had a lot of love in it, just from the electric guitar point of view.

“One interesting thing about the recording of the song was that the arpeggios were done direct, but when I came in to record that day I played John the part and, of course, it had stereo chords and echoes everywhere. And he looked at me and said, ‘Well, I'm not recording that crap.’ He goes, ‘We'll never be able to mix that.’ He said, ‘Can we just plug you directly into the tape machine and get a dry take and then we'll worry about messing it up later?’

“And so we used that black Boogie Strat and we recorded the arpeggios totally dry, no amplifier, just into a mic pre into the tape machine. And then, of course, as we went to layer the track, I realised that he was completely right and he was looking ahead.

“Because that song was difficult; that song's got no drums in it, but there was a drum performance. Jeff Campitelli played drums all over it, but as we were mixing it, we slowly got rid of everything and it was really weird. It was just one of those things where we thought, ‘Wow, can we have a song where the only time there's a kick drum is during the bridge?’ But that's what's there: that was the extent of what we kept of Jeff and the rest of it was Bongo.”

5. Satch Boogie

“I got in a car accident, and I got some whiplash, and I was given a vial of drugs to recuperate, and I was sitting in my apartment in a neck brace, taking these pills. And it came to me that it would be funny if I could write music to the image of the drummer Gene Krupa, playing a drum kit at the top of a flight of stairs and then slowly falling down the stairs with the drum kit and playing.

“I remember playing the idea for Jeff against the drum machine that was just playing quarter-notes, and I said - I think the phrase was - ‘Can I do this? Can it be done?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, that's totally doable! I can do this.’ I was looking for that modernised Gene Krupa swing kind of thing and Jeff is really good at that. I mean, that's right up Jeff's alley.

“And so I recorded the whole thing against a drum machine pattern. The reason why the fade out of the song is so fast is that if we left it linger longer, you would hear the audio of the drum machine leaking into my pickups as I was holding the last chord. So we had to do a really quick fade so you wouldn't hear the ‘doom-dah, doom-dah, doom-dah’ that was pumping through the studio.

“That’s the Kramer into a DS-1 into the Marshall 100-watt. The main head of the song John used a shotgun mic, and then when the solos come in, we use a 57 right up against the grille cloth - that's why it becomes more in your face.

“For the middle pitch axis section, I wanted to take two-handed tapping to some different level, so with Midnight and with this section I was thinking, ‘What has Eddie [Van Halen] not done?’ I mean, Eddie is just a genius. He's the number one guitar player of my generation, but I thought, ‘I'm not going to step on his toes.’

“And so I applied things to the idea of tapping the ’board that I thought moved into an area that Eddie hadn't explored. And then using it as a bridge in a boogie song I thought was the weirdest thing. I just love that. I love it when you do a bridge that's so completely weird that when the song starts up again, you go, ‘Oh, that's right, it's the boogie!’”

6. Hill Of The Skull

“I was reading a poetry book of [Lebanese-American poet] Khalil Gibran, and in there there was a poem written based on eyewitness accounts of the crucifixion of Jesus. And the person refers to it as the hill of the skull. At the time, I'd never heard about that, which was weird because I went to Catholic school as a kid. So I just remember thinking how macabre the whole thing must have been.

“And I was moved to write something that would be so gruesome, like somebody dragging their own cross through the streets of a village only to allow himself to be nailed to it and slowly die. If there was a horror film, people would think it was truly horrible, right?

The first thing I thought was, ‘Get rid of all harmony: no 3rds, no 5ths’

“But sometimes when you're brought up with something from childhood it just becomes part of a story, and you don't really think of the human aspect of it so much. So I was thinking, ‘Well, if I was going to write music to that, it certainly wouldn't be all this glorious religious music I've heard where there's beautiful harmony and the music really alludes to the religious aspects of the event.’ I said, ‘What about the music for the human aspects of it?’ This is the horror of the whole thing. So the first thing I thought was, ‘Get rid of all harmony: no 3rds, no 5ths.’

“And I remember going into the studio thinking, ‘I don't know if I can pull this off,’ and I told John, ‘Look, I'm going to do lots of guitar; it's going to be just Marshalls turned up to 10 and the bass is going to be distorted, but don't be surprised if there's no real harmony. It's just the bassline and the melody, stark.’ And then I told Jeff, ‘I just want you to just hit that crash cymbal over and over again.’ I wish I had a movie of it, because Jeff was in there just going ‘bam, bam, bam’ all the way through the whole song.

“And we had the drum machine doing the kick and the snare. It was heavy in the studio doing it when we put it together, and we just wanted to make it sound scary for what it was. Again, if you remove the religion from it, it's humans being really bad to each other. It's gruesome.”

7. Circles

“I wrote that in the guitar shop where I was teaching; I just remember thinking simple: remove harmony, create riffs that are both melodic and rhythmic. And I think I was trying to imagine cyclical things in our lives, thoughts that go round and round in our head that we can't escape from, or things that we do in our life that we realise 10, 20 years later that we've been on some weird cycle of things. And, so, that got me to create that repetition.

“When I'm writing songs, the main thing is always the story or feeling and emotion, and then there's a part of me that's a musician that says, ‘You know, these are things that I've noticed that I think are unexplored or should be developed from a musical point of view.’ And I use those ideas to help interpret the emotional messages I'm getting about the story of the song.

“And, so, this is a prime example of how I get a feeling, a set of stories develop in my mind around emotions, and then that part, the musician part of me, kicks in and says, ‘Let's run with this.’ And, in this particular case, ‘Let's try and remove excess harmony, don't be afraid of repetition, don't be afraid of simple chords that are really gutsy.’

The great classical composers use complexity and simplicity like they were equal tools. And that's not often the case in modern music

“So that's what led me to the spacey beginning, and then telling Jeff, ‘Look, it's going to be spacey and reggae-sounding in the beginning, but then you come in and just do the most balls-to-the-wall, bonehead thing.’ And he totally got it. I mean, we were just making it up as we were going along.

“The chord progression for the solo is so simple. It's based on I IV V, and there's three chords. But it's the juxtaposition with the beginning and the end that makes it such a release, in a way. And that's what I think I've learned when listening to the great classical composers, that they use complexity and simplicity like they were equal tools. And that's not often the case in modern music. Usually, bands get stuck on one or the other. But classical and jazz music has always treated those two elements equally, as equal tools to send a message to the listener, so this was going through my mind for the whole album.”

8. Lords Of Karma

“Those two chords I wrote when I was still in high school. It must have been about 4.30 in the morning: I came back from a party and I wrote these two chords and I thought they were the most unusual chords. I'd never heard anyone ever put those two chords together in my entire life, and I couldn't write a song around it, they were so weird. And I knew it was a very weird pitch axis thing, and I just kept that in my pocket and I kept waiting to be shown that I lifted it from somebody.

“The record was halfway through its writing and recording, and I realised I really wanted to try to work these two chords into something and I thought, ‘Maybe now's the time: I'm ready, I'm old enough, I'm smart enough to write a song around these two chords that were so inspiring to me.’ And so I did eventually write - it was supposed to be the title of the album by the way - Lords Of Karma.

“That's a Coral sitar - a vintage one that I borrowed from a guy named Ratdog at Subway Guitars in Berkeley, California - playing those opening chords. We recorded it direct and then just applied a really cool mic pre and stuff like that to it.

“It was very strange but that shows how excited I was about the pitch axis concept and how, when I was made aware of it through my high school music teacher Bill Westcott, it was the opening of the heavens from a composing point of view.”

9. Midnight

“Like I said before, I was a big Eddie Van Halen fan, and I just loved playing his stuff, but I could sit back and if I was going to be analytical I could say, ‘Well, he's not doing this. He's taking it in that direction, but what about all this other stuff you could do with it?’

“And, so, again, I tried to be as respectful as I could - I thought, ‘Well, maybe the way to do it is to write a song first and then see if you can interpret it as a two-handed piece.’

I wrote a piece of music based on this baroque music that I'd been listening to and I literally wrote it out on manuscript… And then I thought, ‘Okay, now how can I turn this into a two-handed piece?’

“I wrote a piece of music based on this baroque music that I'd been listening to and I literally wrote it out on manuscript, and it was just chords and a looping melody. And then I thought, ‘Okay, now how can I turn this into a two-handed piece?’ And I spent months taking the thing apart and trying to figure out a way to play it like it was Beethoven or Chopin or something. And that's what I wound up with.

“Then I thought, ‘Okay, now I've got it, it's rather mechanical... how do I create a recording that's rather fantastical?’ Because that was the other thing. I mean, Eddie was all about rock and roll, like fun rock and roll band. Giant guitar hero playing loud, wearing striped clothes and jumping around and trying to avoid the crazy lead singer, that kind of thing. And I thought, ‘What about a pure fantastical thing, like music that is accompanying some weird ceremony in the middle of the night, in the middle of a forest?’ And this is how I would pitch this song to John Cuniberti and Bongo Bob. I'd say, ‘Can you imagine this?’ And they'd look at me like, ‘What?’ [laughs]

“But that's what I did. So I played my black Boogie Strat direct into a mic preamp, right to the tape machine and then we used some sort of stereo chorus and some beautiful reverb, and I recorded all the pieces. I used a little Casio CZ-101 to record the flute, if you can believe it.

“But Bongo Bob, he's such a creative guy, he totally got my whole imagery of a secret ceremony in the middle of the forest, in the middle of the night. And, so, he started to create all the funny percussion, and John was totally cool with trying to get that little CZ-101 Casio keyboard to sound like some sort of dream orchestra. It sounded very much like an old-school Moog synthesizer. It was the cheapest imitation you could ever get. I miss that keyboard. I played it until it broke.

“And the whole thing about the timing, moving, that was my nod to Chopin and the emotional playing and how the music was supposed to be very inspirational. It wasn't all about technique: the problem when you base a song on arpeggios, as soon as they hear [hums arpeggio], right away the listener's like, ‘I bet this is going to go on forever.’ And that's what kills the whole two-handed technique thing, that the audience just knows right away, ‘This is going to repeat, isn't it?’ And then they just check out.

“And, so, I was thinking, ‘Well, then I'm not going to stick to a time signature. There's going to be no click until we get to that middle part, and then that part's going to be metronomic.’ And then the beginning and the end statements are totally freeform, like Chopin sitting down and playing one of his beautiful freeform études.”

10. Echo

“I didn't have anything in mind when it came to sequencing, because there were two other songs that didn't make it to the album. One of the songs called Time that wound up on Crystal Planet that took forever to record, and then the other one was a song called Dweller On The Threshold that wound up on Time Machine, and that was just a very discordant thrash-metal thing.

“It was a good idea we left them off: sometimes you record a song with the best intentions and then you hit play and when it's over you all look at each other like, ‘What the fuck is that?’

“Echo was a song that was about a story I had heard from a relative about a friend of theirs whose first child had died in either childbirth or prior to being born. And when they had their second child, they named it Echo as a tribute to their first child. And the thought stuck with me about different human beings somehow being connected through time, as being part of each other. And, so, that's why the song has a very moody repetitive thing.

We worked random, all-too-human performances around things that were programmed and repetitive

“Now, I'll reach into themes about how I combine repetitiveness with total randomness, and this is the perfect example, because the song is based on metronomic repeating arpeggios in 5/4. Very clever, right, maybe too clever, so when I brought it in I was like, ‘Okay, get this, guys. The drum machine pattern never changes and the rhythm guitar part keeps going for the whole damn song, even though it goes through several different key signatures. However, the melody will be very loose, and then we need to put something on top of it that is randomised somehow.’

“And, so, we would put on guitars playing harmonics, we'd go out and we put on cymbals and stuff that would be very random, never repeating, and they'd just be total one-takes from top to bottom. Jeff would go out there and he would just play cymbals around something that was repeating.

“And this is how we worked random, all-too-human performances around things that were programmed and repetitive. And in my mind I was trying to use the repetitive nature of parts of the recording to tie into the thought that humans are somehow repeats or new attempts at the same energy each time a new person is born. It's a weird science fiction, I guess, that our personalities are unknown. What we do with that, what we do with our lives is something that is randomised, free will, whatever you want to call it.

“Anyway, so it did wind up being the last song on the album just because it seemed so perfect. You know, it's now that I think about it I can swear that Cuniberti came up with the sequence of the record. I think that by the time we got to the end of the record, we were in agreement with how things were going to go in terms of sequencing. But I think I was so distraught over some other elements of the album and how I didn't have any more money to fix things that I hadn't really finalised the sequence. And I remember having a conversation with John and he was just saying, ‘This has to be the sequence, I think. Don't you agree?’ And I was like, ‘That looks great to me!’

“We used a [Roland] JC-120 for almost all of Echo. John had a very clever way of recording the JC-120 with six different microphones, an [AKG] C12A and this and that, and using the DS-1. It was just really interesting how we got a lot of mileage out of that amp. It was the perfect antidote to the Marshall stack or the little Silverface Pro Reverb or Princeton that was there that we used for a lot of the album, too.

“I have to say I'm so happy that people liked [the album], not for the obvious reasons, but because beforehand, when Jeff and I were in a band called The Squares, we realised after a while that it wasn't really the band that we wanted to be in, but if we had huge success in that band that it would have ruined our careers because it was a pop band. It was like the band that has a hit single and then it kills them after the hit single has its run. It just destroys their career.

“But, Surfing With The Alien was the totally opposite. It was a quirky record, out of time with what was happening; it was a weird collection. I wasn't the fastest guitar player, wasn't the most outrageous guitar player, there wasn't anything on it that was right for the time. And yet it did embody a very honest snapshot of who I was as a player, where I'd come from and where I wanted to go.

“And, so, it was the perfect album to become a multi-platinum success, because it actually gave life to my career; it didn't kill it. It wasn't the one-hit wonder thing; it was the opposite of that. It was the opening to a whole career that I wasn't even planning on, and it allowed me these decades of artistic licence, so I'm forever grateful to the fans for liking that record.”

Don't Miss

Joe Satriani's top 5 tips for guitarists

Mike has been Editor-in-Chief of GuitarWorld.com since 2019, and an offset fiend and recovering pedal addict for far longer. He has a master's degree in journalism from Cardiff University, and 15 years' experience writing and editing for guitar publications including MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitarist, as well as 20 years of recording and live experience in original and function bands. During his career, he has interviewed the likes of John Frusciante, Chris Cornell, Tom Morello, Matt Bellamy, Kirk Hammett, Jerry Cantrell, Joe Satriani, Tom DeLonge, Radiohead's Ed O'Brien, Polyphia, Tosin Abasi, Yvette Young and many more. His writing also appears in the The Cambridge Companion to the Electric Guitar. In his free time, you'll find him making progressive instrumental rock as Maebe.