Jimmy Dunlop: “It's the Dunlop way - we’d take a product and deconstruct it, and then rebuild it the way we think it should be built”

We tip our hats to guitar accessory pioneer Jim Dunlop Snr

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The start of 2019 was bittersweet for Dunlop.

The umbrella home of the Cry Baby, MXR, Way Huge and many more pedalboard staples had a triumphant NAMM Show, launching signature products with Billie Joe Armstrong, Jerry Cantrell, as well as updates and new additions to each of its iconic brands.

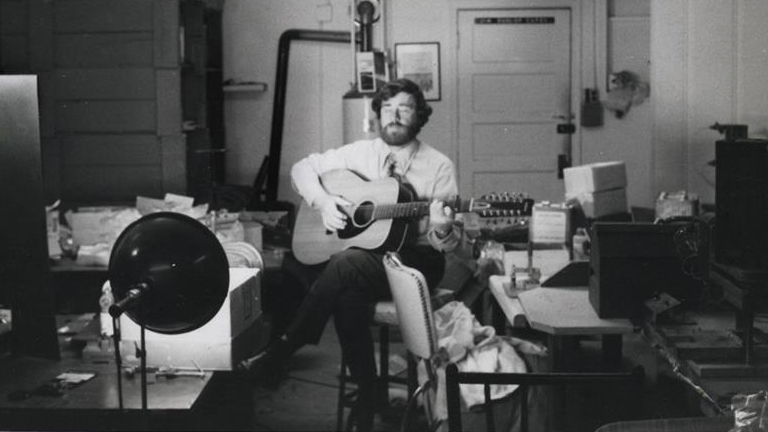

However, shortly after, on the 6 February, company founder and guitar industry pioneer, Jim Dunlop passed away. The loss was felt far and wide, as anyone who’s anyone has at some point played a product not only with Jim’s name on it, but more likely than not, one that he envisioned or improved.

“We always used to say it was like the Dunlop way,” Jim’s son, Jimmy, tells us. “We’d take a problem or take a product and deconstruct it, and then rebuild it the way we think it should be built.”

However, this is certainly not the end for Dunlop - Jimmy has been a part of the company for over 30 years, continuing Jim’s groundbreaking work with his own developments. Here, we speak with Jimmy to find out about the most recent addition to Dunlop’s pick line, the Flow Tortex, as well as finding out the brief history of how a young Scottish engineer came to be a visionary of guitar products.

How did Jim’s engineering background shape what he did?

“I’ve seen it said in so many articles that Jim was a chemical engineer, and I have no idea where that came from. He started out working in the shipyards, for Barr and Stroud who made lenses and optical devices, scientific equipment for ships. He left school at 14 to become an apprentice at Barr and Stroud, and so he was trained at a very young age to be meticulous and very precise. He worked the lathe, he could create things with his hands. So that’s where it all came from.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Was he already a guitar player?

“He was a guitar player. It wasn’t like he was a super-technical guitarist: he played for parties. He was very Scottish! It was the harmony, the sing-song and passing the guitar around the room having fun.”

Go west

How did Jim end up in the US?

“He migrated from Scotland to Canada, he met my mother, and he crossed the border to the US. She was seven months pregnant, and they drove out to California. He’d been offered a job, but when he got there, they couldn’t believe that he had seven years’ experience like he’d written on his CV.

“He showed up, a guy in his early 20s, and they said he must have lied on his application - they didn’t believe him because people just didn’t start work at 14 in the US! So he ran around, trying to find a job to feed his wife and soon-to-be child. He did whatever he could, tried to get a job as a machinist, he sold nuts in bars, he did a lot of things to try and make ends meet. He wound up at this company making scientific equipment, so he could use the skills he’d learned at Barr and Stroud.”

So how did that lead to designing the first products?

Everything he worked on, it was spawned from Lundberg’s shop, and [Jim] was just this cool young Scottish guy who played guitar and wanted to develop products

“The president of the company was a guitar player, and so they came up with this idea of having a Vibra-Tuner which was a reed with a suction cup on it. You’d attach it to your guitar and the reed would resonate within a certain limit. He worked all day, then worked nights trying to develop this product with his boss. Then six months in, his boss said, ‘You know, this is going nowhere. I’m going to give up.’ My dad was like, ‘I’ve spent six months of my life working on this product. I’m going to finish it.’ So he did, and he took it around all the guitar shops in the San Francisco Bay Area trying to sell this product, and it was a complete failure!

“This was during the beatnik era, and San Francisco was kind of the epicentre. There was a famous shop there and the owner was a world-class luthier named Jon Lundberg. Everybody took their guitars there to be repaired. My dad was hanging around there and one day he says to Jon, ‘I’m a machinist - what would make sense for you guys [guitarists]? I can do it!’ And Jon goes, ‘You know, a lot of these guys are playing 12-strings, and there’s not a capo out there that works right on a 12-string.’

“So he went back to his house and started working on what is now the 1100 series capo. It was his machinist background; he developed that toggle action and made it specifically so it would hold down a 12-string. He brought it back to Lundberg’s, and they loved it, so he got the nod from the luthier of choice for everyone.

“Two years later he goes back and says, ‘What else can I do?’. Jon says, ‘A lot of guys are using finger picks but they have problems with them destroying their cuticles, they really hurt!’. So he developed the 33R. Everything he worked on, it was spawned from Lundberg’s shop, and [Jim] was just this cool young Scottish guy who played guitar and wanted to develop products. It was just wide open.”

It seems like Jim had that entrepreneurial spirit from a young age...

“When I tell this story, it seems like Jim was this fearless guy coming out of Glasgow. He went to Canada, crossed the border with $600 in his pocket and was up for anything. The fact that he showed up in Berkeley during the golden age of folk music - he was the right guy, with the right skills in the right place at the right time. It was just this perfect storm. He was there during that golden era of rock and roll, so it’s not like some other companies today. He was actually there.”

Precision picking

That precision mentality sums up what you said about ‘The Dunlop way’...

“For an American company, everything is done in millimetres! He was using the metric system back in the mid-60s in the US. When you look at the nylon pick, it’s 1.0, .88, .73, .60, .50, .46 and .38. He was really homed in on the precision. Before that, there was just light, medium and heavy, and never consistent! The slides are the same, all done in the metric system. Nobody cared about weight or size before; you were just cutting off bottle tops! He got in there and developed a standard of measurement for all of the guitar products; he was the guy.

There was no accessory line back then; he was developing the modern day accessories

“The way the whole company evolved, it’s not like today where someone says, ‘We need to have an accessories line!’. There was no accessory line back then; he was developing the modern day accessories. After that he got into tone bars, because he was buddies with Ernie Ball. Ernie was a lap steel player and he asked Jim, ‘Can you make these for me?’

“He was a very good friend and an inspiration to my dad. I think he was a real role model [to Jim]. He was kind of a one-man band, and he only did as much as he could handle, so doing the capos, fingerpicks and tone bars at that point was a lot.”

So from here the company started making picks?

“At that time, celluloid was king. I remember in the 70s, my dad had celluloid picks with the Jim Dunlop logo on them, but he wasn’t making them at that point. I think when he developed the nylon pick, the reason it took so long was because he didn’t have the money for the moulds. He was a Scottish immigrant, you know! He paid for everything in cash and only moved as fast as he could. So when he had enough money to purchase moulds, he got into it, but he wouldn’t borrow any money to get into that.

“The kings of nylon picks at that time were Moshay and Herco. We own Herco now, but at the time they were pretty precise, but they weren’t making their own products. They had the Flex 50 and the Flex 75, but I think Jim saw an opportunity there to make nylon picks into a full range, with proper grips that actually worked and was even on both sides.”

The Jazz III has become an icon of the pick world...

“The Jazz III came in 1976; ‘75 was the nylon standard. It’s funny, everything was kind of based around the NAMM Show back then, and he was a real stickler for making sure he had something new to show. He was looking at shapes, and he’d had success with the Nylon Standards so it was kind of like, ‘What’s next?’

“Fender had their teardrop picks, and Gibson also had one. He really wanted to do something different with a small pick. He was an avid reader of Guitar Player magazine; he really considered that to be the bible, and I think he was in the first issue. He was into all the articles about what the jazz guys were using. He read every article about guitar picks, so the reason the Jazz I, II, and III are what they are is because of the information he read in Guitar Player about profiles and shapes and thicknesses.

“The funniest thing about the Jazz III is that it’s not just a jazz pick. You think about Petrucci or Kirk Hammett when you think of that pick!”

Tortex

And of course there’s the trademark Tortex material too...

“Tortex came in 1981. It’s a different process than the Standard Nylons. It’s a punched pick - punched and tumbled. I think what they were looking for was something more rigid. Nylon can heat up a bit and it absorbs the sweat, so it softens up a little bit. So they were looking for something that was a little more stable with a faster attack.

I have a ton of old vintage tortoise shell picks in my collection, and I really feel that Ultem emulates that the closest

“I think that if you look at what we’ve done through the years, you can either improve guitar picks through materials, or through shape and form. At that point there was celluloid or nylon, or real tortoise shell which was banned. And tortoise is kind of the Holy Grail, with that nice bright tone as opposed to celluloid that wears down real quick, or nylon that isn’t as bright.

“The ‘tex’ part of the names usually means that they are tumbled, so there’s a texture to it. They’re tumbled in a machine with a tumbling media - polishing rocks - to bring down the edges. Tumbling is a real art form, definitely.”

Where is Ultex in the range?

“Ultex is an Ultem material, which is aeronautical-grade plastic. Ultem really delivers a bright, punchy sound; it really emulates tortoise shell the closest to me. We’ve been doing them for about 17 years now. I have a ton of old vintage tortoise shell picks in my collection, and I really feel that Ultem emulates that the closest with the clarity and volume. And because of how we make it - we mould it - and there are several shapes: Standard, Jazz and The Sharp, which is actually a copy of one of my favourite tortoise picks that I own.

“Then you get into the Primetone picks that we have, and they have the hand-bevelled speed bevel to them. It’s like a pre-worn or customised pick; some of the flatpickers sand their picks to get the angles more worn.”

It’s clear Dunlop thinks about every area of a guitar pick...

“We make these picks, and I have a group of friends who are pick fanatics. We really run them through their paces before we bring them out. It sounds crazy, but we spend a couple of years putting this stuff together. When we come out with a line of picks, it’s not like we’re just making a CNC version of them. We’re making moulds; it takes a lot of time. Over the last few years we’ve really spent a lot of time perfecting a comfortable grip - trying to get that balance of it being there but not being there: functional but not in the way.

“I find guitar picks inspiring. I hope that other people do, too. I think that every pick, shape and material has a different tone and feel, and it inspires you to play in different ways. It’s the first point of contact with the guitar, and you have to address your instrument correctly.

“Using the right pick is the first step to getting the tone out of your guitar. It’s the easiest way to EQ your guitar, too. If you have a guitar that is super bright, you can use a nylon pick or a celluloid pick and really change the tone of the instrument. If you’re playing acoustic and need to raise the volume, using an Ultem pick will make you louder and brighter.

“Picks never get boring for us here; we’re always looking for a way to make it more inspirational for guitarists so they can practise longer and just really enjoy their instruments. I’ve been doing it for 30 years and I feel we’re just coming up on our coolest stuff right now. We really take pride in trying to respect tradition, but still innovate.”

Total Guitar is Europe's best-selling guitar magazine.

Every month we feature interviews with the biggest names and hottest new acts in guitar land, plus Guest Lessons from the stars.

Finally, our Rocked & Rated section is the place to go for reviews, round-ups and help setting up your guitars and gear.

Subscribe: http://bit.ly/totalguitar