The story of John Lennon's lost Gibson J-160E acoustic guitar

An acoustic detective story

Introduction

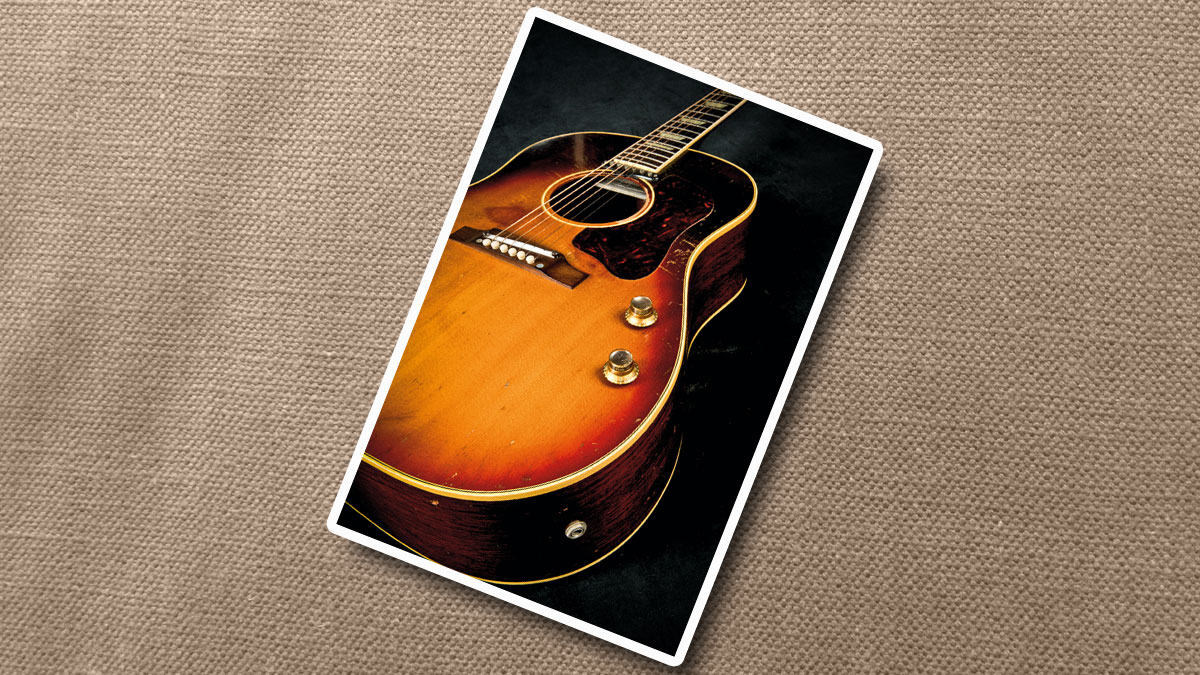

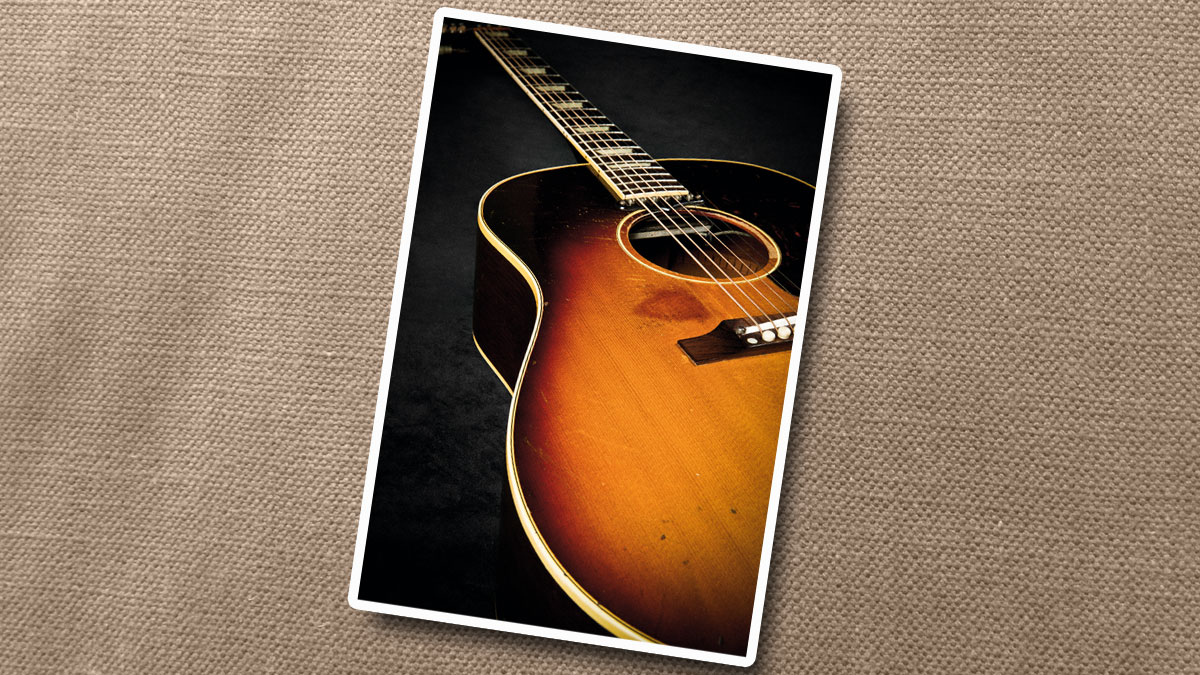

The story belongs in a film script - a man buys a used acoustic for a few dollars and plays it for years. Then, one fine day, he discovers he has in his possession one of the most important ‘lost’ guitars in rock history. We find out how John Lennon’s Gibson J-160E acoustic guitar, which was used to record some of The Beatles’ legendary early hits, resurfaced in California last year, solving a 50-year mystery.

When the gavel finally fell in the auction of John Lennon’s ‘lost’ 1962 Gibson J-160E acoustic in California last November, the bidding closed at $2.4m. For John McCaw, who had originally bought the guitar for just $175, the hammer’s crash also marked the end of a remarkable piece of detective work - and a kind of farewell.

To John it was simply a pleasant old Gibson that he enjoyed picking bluegrass on

John bought the guitar in 1969 from a friend, Tommy Pressley, who had picked it up at a San Diego music store called The Blue Guitar two years previously.

Neither man had any inkling at the time that the guitar had previously been the main squeeze of John Lennon, who originally bought it at Rushworth’s Music Store in Liverpool in September 1962, for just over £161, and used it to create some of the most famous tracks The Beatles ever waxed.

Incredibly, She Loves You, I Want To Hold Your Hand, All My Loving and other epochal hits were all either written or recorded with the very guitar that casually changed hands that day.

“I bought it from a friend of mine who was leaving town and needed some money to make a move to northern California,” John McCaw recalls.

“I’d tried his guitar out for a couple of years and I always liked it. And when he offered it to me, I jumped at the chance to buy it, because we were into country and western and kind of bluegrass at the time and it was a perfect guitar for that music.”

For decades afterward, it hung on the wall of John’s house in San Diego, much-loved and often played, but obscure. With no hint that the guitar had a famous past, to John it was simply a pleasant old Gibson that he enjoyed picking bluegrass on. But the secret that lay within its timbers was not to remain dormant for much longer.

By George

It took, of all things, a Tuesday-night jam to set the seized-up wheels of history in motion once again. John McCaw’s guitar teacher and friend Marc Intravaia picks up the story:

“In April of 2014, John was at my Tuesday-night guitar group that I’ve been hosting for six years and he saw a magazine sitting on a bookcase and on the cover was Dhani Harrison. The feature was to promote Dhani’s app, and there were photos of George Harrison’s guitar collection in there.

The curious proximity of the guitar’s serial number to that of George Harrison’s prompted John McCaw to investigate

“And when John flipped open the magazine, there was George’s J-160E and the picture showed the serial number. And John turns to the group and goes, ‘Hey everybody, mine’s only four serial numbers away from George’s: now I know it was made in 1962’ - and everybody was like, ‘Alright!’ He’d been bringing the guitar to my guitar group for six years and nobody thought anything of it.”

The matter might have rested there, but the curious proximity of the guitar’s serial number, 73157, to that of George Harrison’s (73161) prompted John McCaw to investigate the details of his own guitar more closely.

Lennon and Harrison had both bought J-160Es on hire/purchase at the same time as special orders from Rushworth’s, and they were treasured possessions not least because, adjusted for inflation, the cost of each instrument would be around £3,000 today.

Gradually, and with a growing sense of incredulity, John McCaw started to notice striking similarities between the J-160E in his possession and archive images of Lennon’s instrument. He also learned that Lennon had lost such an instrument on tour in 1963 - Beatles roadie Mal Evans even recalled that mislaying the guitar was the “worst” moment of his long career with The Beatles.

We can work it out

At the time, however, the loss was slow to be noticed. By the time John’s guitar went missing during The Beatles’ headlining Autumn Tour of Britain and Ireland in ’63, which began that November, Lennon was using a Rickenbacker 325 as his main stage guitar.

It was, reportedly, not unusual for both Lennon and Harrison to take one of the ‘Jumbos’ home between shows

With his J-160E often taking a back seat, it was, reportedly, not unusual for both Lennon and Harrison to take one of the ‘Jumbos’ home between shows, meaning the absence of Lennon’s guitar was not clocked until the end of that winter’s touring season, when the band were playing a London show.

By that point, it was presumably too late to determine where on the busy schedule of shows it might have been lost and under what circumstances. How the guitar then reached California remains a mystery, but it has been conjectured that it subsequently found its way into the hands of another British band who later toured America and passed it on there. That remains very much an unsubstantiated theory, however, though temptingly plausible.

Sorely in need of a second opinion, John McCaw decided his next move should be to share his discoveries with Marc Intravaia, who remembers the moment clearly.

“John came back to me on 21 August 2014. He’d booked an hour-long lesson - but he comes in and he’s very serious and he says, ‘Hey, I don’t want a lesson; I want to talk about my guitar. I’ve been doing some research and John and George got theirs in Liverpool on the same day in ’62. And then John’s went missing after a Christmas show in December 1963’. And he said, ‘Can you help me?’ And I went, ‘Okay.’ So I pulled up a video on YouTube, and just searched for The Beatles and the first video that I saw was I Want To Hold Your Hand.”

Coincidence or not?

“And there was footage of John and George with their J-160s. So I put that up on the screen and we propped the guitar up against my desk and we started watching the video and pointing out these different scratches and scars and we were like, ‘Hey, you have that weird guitar-pick shaped mark behind your soundhole… John’s has the same one.

“And then the detail that really got me super-excited, and John, too, was that Lennon’s guitar had a one-inch, fish-hook shaped scratch. And in the video, the studio lights kept reflecting off this scratch and we were looking at John’s guitar and it had the same one. And that’s when we both kinda looked at each other and went, ‘Oh! I think you have something here.’

The studio lights kept reflecting off this scratch and we were looking at John’s guitar and it had the same one

“Then, funnily enough, we went back to the studio and John had 10 minutes left on the lesson he paid for. So we kind of looked at each other and went, ‘Okay, so let’s get back to A minor pentatonic scale…’ And we went back to his lesson after all that!”

John and Marc also approached a friend who owned a major archive of high-resolution stock footage of various rock artists, including The Beatles. They pored over image after image of the instrument and kept finding fresh similarities, until they reached the point where they felt confident enough to contact Beatles gear expert Andy Babiuk (read more on Babiuk’s process of authentication in Tell Me What You See, p62) to seek an independent verification that it was the same J-160E that John Lennon had lost while on tour in ’63.

“We approached Andy Babiuk and a week or so later, he got back to us and he verbally authenticated it remotely from his place in Rochester, New York,” John recalls.

The news was dumbfounding and instantly changed his relationship with a guitar that had been a casual jamming companion to that point. He consulted further with Andy Babiuk and soon saw that it was imperative to inform Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s estate about the find.

Go to Yoko

While the guitar was never formally reported stolen at the time that Lennon lost it, and had subsequently been bought, sold and bought again at least three times, in good faith, it was clearly a prudent and necessary step - especially as John felt increasingly uncomfortable in having such a valuable and historic guitar in his possession and had already decided that he wanted to offer it for public auction.

John took steps to ensure that when the news went public, the guitar would not perform a second disappearing act

“After the authentication, Andy Babiuk introduced me to Darren Julien of Julien’s auction house. And he has a relationship with Yoko and the estate, as Andy did. Both of them suggested that we get ahold of them and Yoko, and I agreed.

What I wanted to do was get in touch with her to let her know the guitar had been found and get her blessing… because we did not want to blindside her and just throw it out there that it was going to auction. I didn’t feel that would be right. And so Darren made the initial call to her and let her know - and then, from that point on, with my advisors and her attorney, we talked and the blessing was given to push ahead with the sale.”

John and Yoko Ono agreed to split the proceeds of the sale and, with that significant rubicon crossed, John took steps to ensure that when the news went public, the guitar would not perform a second disappearing act.

Keep it secret, keep it safe

“I didn’t know how quickly news would spread about it,” John McCaw recalls. “I figured like wildfire - because it was such a fantastic story and I just didn’t feel safe having it in my house.

“I was also afraid for my family if, in my absence, somebody tried to break in and take it away or what might happen. So I hired a vault. And I stored it in a very safe vault and kept it there for about eight months, except for when I would take it out to play it.

After we found out, it really did feel different: it sounded different, it played different

“I loaned it to Marc to record a couple of times and another friend of ours, and I shared it around with people who had gotten involved with the story as it evolved. So I got it out as much as I could, but it was no longer in my house - it just was not comfortable having it there, quite frankly. And I knew we were on our way to auction and we certainly wanted the guitar to be there on auction day.”

That day came on Saturday 7 November of last year, but not before John McCaw had held a farewell party for the guitar before it went up for sale. John recalls how different the guitar felt to play and hold once everyone knew what it had once been, what music it had been party to creating.

“We had a going-away party for it, the day before I turned it over to Julien’s auction house last June. We had a crowd of probably 40 or 50 people there and I told them that after we found out, it really did feel different: it sounded different, it played different,” John reflects.

“It just had John Lennon’s aura, his soul wrapped around it in many different ways. And everybody who had played it prior to our discovery, and who I let play it after our discovery, would tell you the same thing. It just was a different feel. There was a reverence to it that was inexplicable.”

Under the gavel

The guitar sold the following day to an anonymous buyer, and John says that even he has no idea who the current owner is.

“The buyer is anonymous and wishes to stay that way,” John explains. “I do not even know who it was. I enquired, but I have been told that, due to a confidentiality agreement, the only time even I will find out is when he chooses to come forward.

Now that the dust has settled on the whole adventure, what has John replaced such a momentous guitar with?

“Some of the big-hitters who had shown an interest in the guitar before the auction said they would share it and display it and so forth. And I was hoping that something like that might happen, but it didn’t and I had no control over that, so I can’t cry over spilt milk. The guy’s got a good guitar, he paid a lot of money for it. So I know he’s happy with it and I hope he remains so.”

So, now that the dust has settled on the whole adventure, what has John replaced such a momentous guitar with? The answer is simple - another vintage J-160E, of course! Though this time, John is happy for it not to come with any gobsmacking backstory, he says.

“It’s a nice one and it fits right on the wall and it fills a void that was there for the last year. And it looks great - I’m really happy with it.”

Beatles Gear: The Ultimate Edition by Andy Babiuk is available now, published by Backbeat Books. For a closer look at 10 essential instruments from the tome, head over to our Beatles career in gear.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.