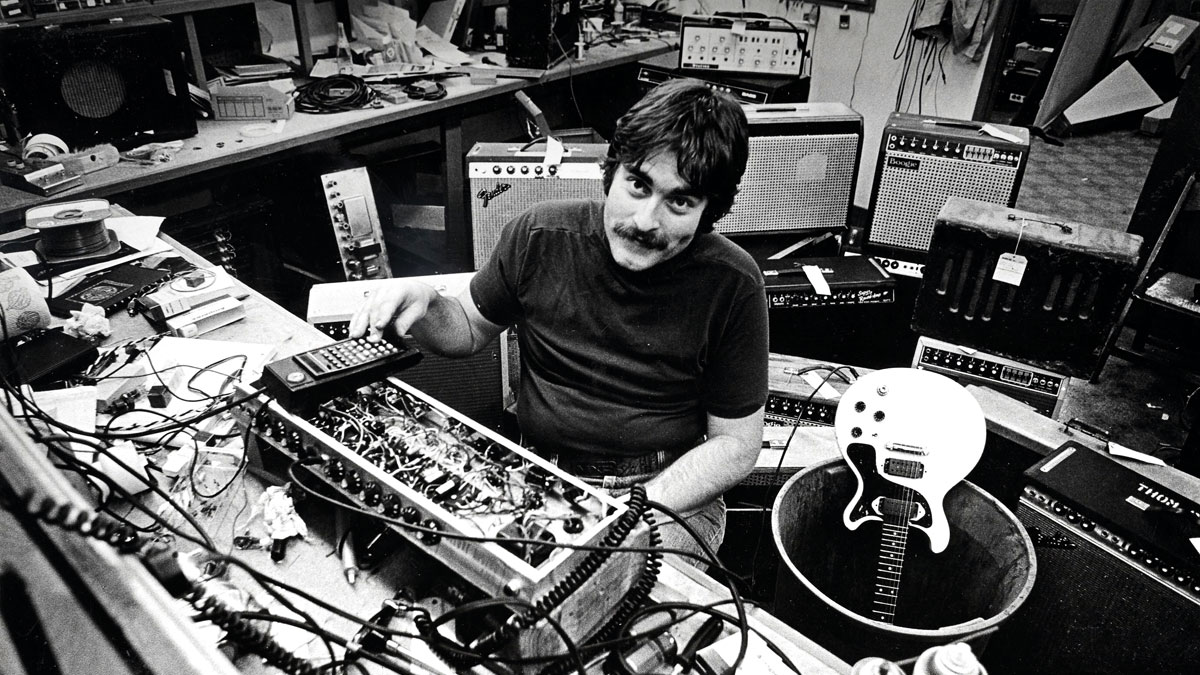

Paul Rivera on modding Marshalls, Eddie Van Halen and the 80s session scene

The legendary amp tech/builder talks

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With shred pioneers such as Eddie Van Halen pushing amps to the brink in the late 70s, Paul Rivera began hot-rodding Marshall heads to squeeze ever more from them. Here, this now-revered amp maker recalls how he sought to make the "ultimate Marshall".

Paul Rivera's career started in New York, but took off when he relocated to California in the early 1970s, working from a shop located over Valley Arts Guitars in North Hollywood on the edge of Studio City.

While most of us in the UK remember him for his association with Fender, Rivera's custom work on Marshall amps and pedalboards is just as significant.

We meet Paul for a rare interview in which he explains how he got into modifying amps and gives us a unique Californian perspective on the Marshall sound.

When did it all really start for you - was Valley Arts the beginning?

Paul Rivera Sr: "At that time, Valley Arts was the epicentre of the whole LA studio scene. I didn't realise it back then, but it was a golden era for the guitar and guitar players.

When Eddie did Beat it for Michael Jackson, he was using one of my modified Marshalls

"My work for those guys started with Dean Parks and he turned me on to Larry Carlton, who in turn introduced me to Jay Graydon, then Lee Ritenour.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"This was alongside some of the top jazz cats like Thom Rotella, Mitch Holder and, of course, the infamous Wrecking Crew, which included Dennis Budimir and Tommy Tedesco."

What drove the amp-modification business for you back then?

PR: "Well, having gotten established at Valley Arts, pretty soon it seemed that if you showed up to a session and you didn't have a Princeton or a Deluxe or a Marshall modified by Paul Rivera, you didn't have the latest thing.

"There was definitely an element of competition between some of those session guys to have the latest, coolest sounds, which kind of drove my modification business forward.

"I started doing pedalboards, too, because the pedalboards these guys were using were so primitive. Nobody knew about buffer stages and that stuff. I think, to some extent, I was mirroring what Pete Cornish was doing in the UK."

What kinds of mods were players requesting, and how did you provide them?

PR: "I brought a lot of mods to the Marshall and did a lot of R&D on them, which led me to guys like [former Van Halen bassist] Michael Anthony and Eddie Van Halen in around 1979, where I did a lot of stuff on their effects racks.

"When Eddie did Beat it for Michael Jackson, he was using one of my modified Marshalls. Then came Steve Lukather, and Eric Johnson whose Marshall amp I worked on in 1980 and '81, which was at the very tail end of my stint at Valley Arts, just before I got hired by Fender.

"By this time, I had a range of different modifications, called Stage 1, 2, 3 and 4, leading up to my 'ultimate Marshall', which had true dual-channel switching and effects loops with bypasses.

"That was all done with silent optical switching and dual-concentric stacked control knobs on the front panel, which I did to save drilling extra holes and keep the appearance as stock as possible.

"On the sound front, some players were more articulate than others with regard to what they wanted. Jay Graydon was technically very articulate. He'd play me a note on his 335 and say, 'You hear how it goes skinny up there? Can you put more body on that, and maybe do something to mask the fret noise?' That's how things often got done."

Was reliability an issue on some of those old amps?

PR: "To get some of the high-gain dual channel stuff, sometimes you'd wind up with six or seven tubes in a preamp that started with two, and if you didn't pay any attention to the power supply, reliability would suffer. So yes, at the extreme I would be replacing power supplies, adding regulated DC heater supplies and so on.

"Probably the finest and most reliable hand-wired amps I ever saw were the early Hiwatts. The lacing on the wires and the solder joints was just a delight to see. I don't think I ever made a hand-wired amp as pretty as a Hiwatt, but I always tried to make it as bulletproof.

On some amps there's a collision of different things that add up to a particular tone and response that's almost voodoo

"Reliability was always - and obviously still is - vital to my customers. Back then, if a session guy's amp went down halfway through a date, he would sacrifice his money and probably wouldn't get called the next time."

How much did you experiment with loudspeakers and cabinets?

PR: "A lot. Loudspeakers are the ultimate mechanical filter. For guys who were going out on the road and needed the ultimate in reliability, we often used the Electro-Voice EVM12L, because if you have a 25-watt amp running into a 200-watt loudspeaker you know you aren't going to have a problem.

"The issue there was more about getting the cone moving. Those EVMs have very stiff cones and spiders. At low level, they were the coldest, least inspiring loudspeaker you ever heard, but turn them up and they were magical."

What do you think are the essential elements of the Marshall head-and-closedback-cab sound?

PR: "Where Marshalls are concerned, the classic pre-1972/'73 1959 Marshall is basically a 4x10 Bassman circuit with a few tweaks.

"In around 1972 or '73, Marshall changed their transformer spec to get a little more reliability, because pre-change, with the power transformer at full whack, they probably exceeded the thermal capacity of the tubes they were using. In spite of that they certainly sounded fabulous, all the way up to where they exploded!

"From what I could see, there wasn't so much attention being paid to reliability on early 1959s, because those tubes were being pushed so hard. Mullard and Valvo EL34s can handle 600 or 700 volts on the plate, as long as the screen voltage is kept down, but it wasn't.

"I think on some amps there's a collision of different things that add up to a particular tone and response that's almost voodoo, and the early Marshall 1959 has that.

"Partly in the lower gain preamp, which results in the output stage providing some of the drive, partly in the transformers, and, of course, the speakers and 4x12 cabinets."

What about some of the later amps, such as the JCM800?

PR: "The JCM800 was interesting, because it was a more modern take on that classic Marshall tone. I designed a lot of tweaks for it - nothing that would necessarily make it sound better, just different.

"'Better' is a very subjective thing. I didn't find the JCM800 to be very consistent, but a lot of that was down to the valves they used at the time. Also, Marshall tweaked the JCM800 several times over its lifespan, so they varied quite a bit coming from the factory.

"I fitted 'fat' switches and there was also some tailoring to the EQ in between gain stages, to smooth out the top end and tighten up the bass so it didn't sound so ratty or bloated.

"So a Les Paul with humbuckers wouldn't sound flabby, while a Strat could still sound fat with the pickups wound down to where you didn't get the magnets interfering with the strings.

"On a lot of old Marshalls I would get them with the filter capacitors shot and then we'd work on the power supply to take a little bit more of the ripple out and that would assist in removing ghost notes from power chords and so on.

My favourites are the original 1959s and JTM45s before the early 1970s transformer changes

"Marshalls in the States sound different to the way they do in the UK, because of the difference in the mains frequency - it's not apparent when you play clean, but with distortion there are all kinds of intermodulation effects.

"In Japan, where half the country is on 50Hz and the other half is on 60Hz, you can go from Tokyo to Osaka and your amp will sound different."

What are your favourite Marshalls?

PR: "My favourites are the original 1959s and JTM45s before the early 1970s transformer changes. If you had good valves you could keep them working and they were so musical and they had a lot of magic.

"Unlike them, our amps have a lot of gain, but it's still about keeping them musically responsive so they do what a player asks them to do. I tend to think that Marshall somewhat bottle-necked themselves, because they had this concept of 'The Marshall Sound', which they continue to chase, but on the early amps it wasn't about that, it was their transparency and response that made them work so well.

"As guitar players we're all on a never-ending quest for great tone, and that's really what Rivera has always been about, helping players find a way to get closer to that sound they hear in their heads, whether it comes from a small combo or a 120-watt stack. Great tone is a universal truth for us all!"

Don't Miss

50 years of the Marshall stack: the birth of the 100-watt stack