In pictures: 1964 Marshall JTM45

50 years of the Marshall stack: up close with a classic amp head

Introduction

The JTM45 was first-born of the Marshall breed and the earliest examples of this amp, featuring an Art Deco-style ‘Coffin’ logo, are very scarce. So when vintage-amp restoration specialist Neil Perry was tasked with restoring a long-dormant ’64 example to life, he had to tread very carefully indeed. Join us as we put all his hard work to the test by cranking this fully fettled vintage beauty all the way up.

It’s the kind of find we all dream about: a historic vintage amp, bought in the years before such things became sought-after, that has been quietly dwelling in a cupboard for years and has now come to light once again, in timemachine condition.

The 1964 Marshall JTM45 MkII we’re looking at hails from an era when music was on the brink of a revolution

The 1964 Marshall JTM45 MkII we’re looking at hails from an era when music was on the brink of a revolution. It was built only months after The Beatles released their debut studio album, Please Please Me.

Two more years would pass before Eric Clapton recorded the ‘Beano’ album with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, while Hendrix’s Woodstock performance was still half a decade away.

And while its quaint Art Deco ‘Coffin’ badge harked back to the swing bands of the 1930s, the sounds it was capable of generating ushered in a very different era of music: that of blisteringly powerful blues and rock, delivered at volumes that you could feel in your bones as much as hear.

The JTM45 was, undeniably, heavily based on Leo Fender’s 5F6-A Bassman. But the use of British KT66 output valves in place of the Bassman’s 6L6s (5881s were also used), plus differences in the spec of preamp valves (ECC83s in place of 12AT7 and 12AY7s), transformers, caps and, of course, cabinets make Jim Marshall’s baby a very different amp.

This particular example returned to the light of day when its owner, who wishes to remain anonymous, brought it into Vintage & Rare Guitars in Bath to see if it was worth putting on sale. Rod Brakes, the shop’s proprietor, takes up the story:

“The owner originally bought the amp when they weren’t worth very much,” Rod explains.

“I don’t think he was the first owner but he bought it fairly early on. And it was just one of those classic stories: he’d used it and gigged it and he also had a ’62 ES-335 with PAFs and all the rest of it.

“But unfortunately, he can’t play any more and he’s getting on a bit, so he phoned up and said, ‘Can you help me with this at all?’”

Rod told the owner that early JTM45s were now highly sought after.

“It’s very unusual to see those amps - they’re almost more few and far between than a lot of vintage guitars,” Rod comments. “And it’s even more unusual to find them in a state where you can play them.”

Firing Blanks

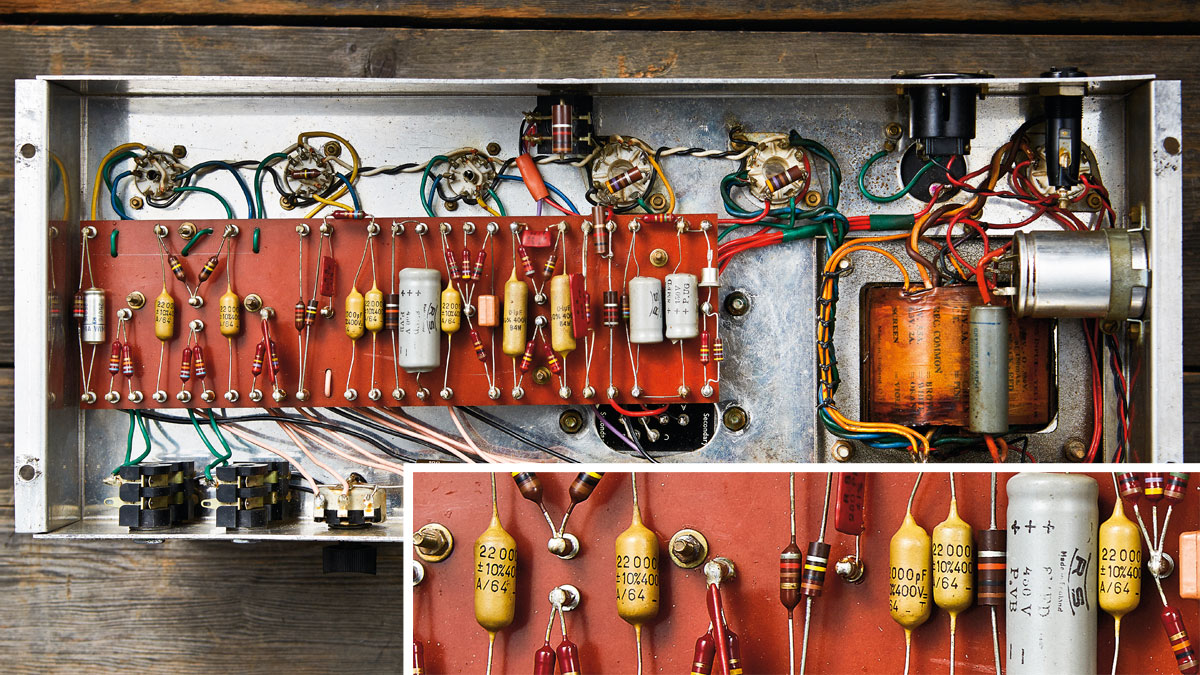

Despite its promising condition, the amp hadn’t been fired up for many years and, without a careful inspection, there was a real risk an ageing component might blow - including the original RS Transformers that are so important to the amp’s sound and feel.

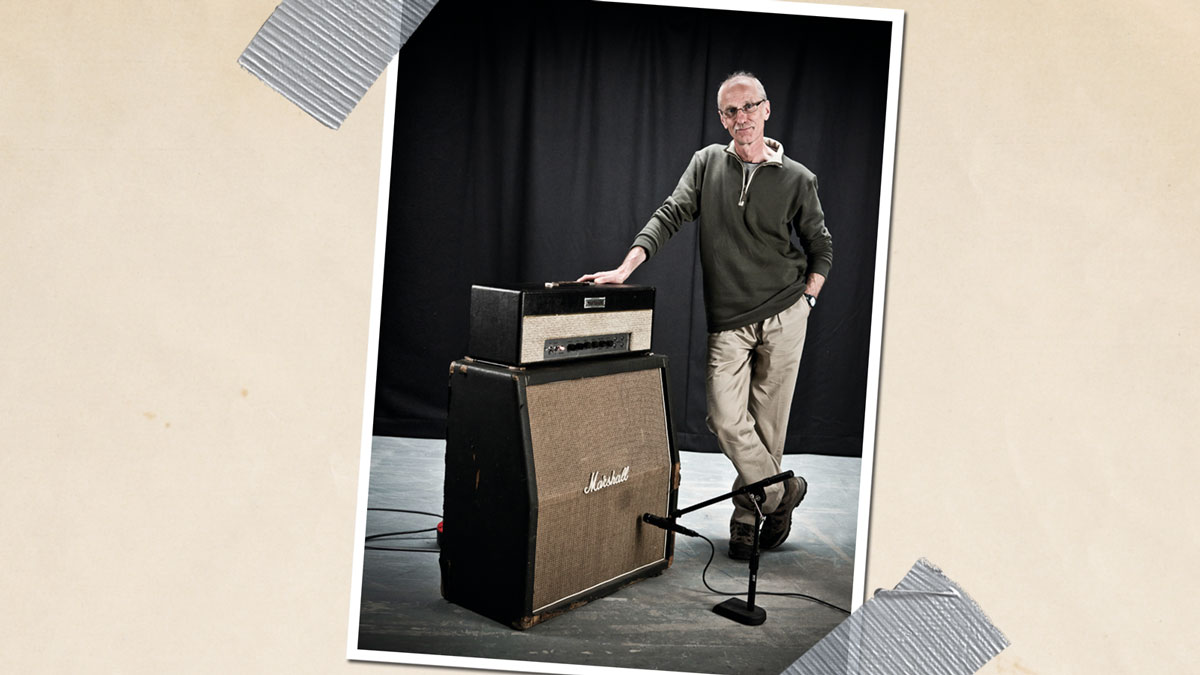

So it was crucial to ensure that the amp was in sound condition, electronically, before powering it up. Enter Neil Perry of Raw State [pictured], who specialises in restoring vintage amps to working condition.

The 1964 Marshall JTM45 MkII we’re looking at hails from an era when music was on the brink of a revolution

Neil counts the likes of Adrian Utley from Portishead among the star guitarists who entrust their old amps to his care and so he was the perfect person to undertake the painstaking inspection that would tell the amp’s owner whether it could even be safely switched on.

“It hadn’t run for quite a while,” Neil recalls, “so the first thing you want to do is make sure you’re not going to blow it up just by turning it on, which is the easiest thing in the world to do with any old amp, or any old piece of machinery.

“For example, if you had a beautiful old Ferrari, you wouldn’t just get in and try and start it up and drive off because you’d probably wreck it.

“So, instead, you build the old capacitors up again with a slow trickle of voltage to make sure that everything’s okay. Then you test each component, to make sure that they’re not so far out [from their original performance envelope] that they’re just going to pop - because obviously if you blew an output transformer or something then that would be serious. After that, you check the valves and clean every contact. Then you’ve got a chance of firing the amp up safely.”

It was quickly apparent that Neil’s caution was justified, as the amp’s dormant years had taken a toll on some of its parts.

“The switches, for instance, were completely useless,” Neil says. “They didn’t actually switch. So we just soaked them overnight with a little bit of contact treatment oil, so they’d actually work.

“Also, the output valves were old but they didn’t really match. Both were Marconis but they’re not from the same year and don’t even represent the same version of the KT66. And, in fact, they mismatched quite badly, so they wouldn’t really do the amp any favours tone-wise.

“Possibly one was original, and one added later - but you just don’t know. So that’s why we’re running on some Genelecs now, although we kept the originals.”

Don't Miss

50 years of the Marshall stack: the birth of the 100-watt stack

NOS replacements

Overall, however, the amp - a Second Series JTM45 with aluminium panel and Vynair white cloth front - was in remarkably good, near-complete original condition.

Neil replaced a couple of iffy resistors with era-appropriate NOS replacements, carefully balancing practicality with the need to keep the character of the amp as original as possible.

When working on vintage amps, this involves a careful assessment of whether to replace parts that are functioning safely but not necessarily to ‘textbook’ values.

Things ‘drift’ over time - but sometimes the effect of that drift can sound cool

“Things ‘drift’ over time - but sometimes the effect of that drift can sound cool,” Neil says. “So when you work on an amp, sometimes you don’t actually want to lose that amazing thing that’s happened. So you’ve got to be careful.

“Nonetheless, when parts are on the brink of failure, prudence dictates that they’re replaced before they blow and cause catastrophic damage to other parts of the amp,” he adds.

“I had another Marshall in for repair where the output valves were completely wrecked,” Neil recalls. “And I thought it was strange because the guy who owned it didn’t use it that much anymore. And what had happened was that all the components in the bias section had drifted right off spec, so the valves were running really, really hot.

“So if you’d left that much longer they might have just popped and then you’d risk losing your output transformer and that’s a big problem. So if you just change those few resistors for a few pence, your amp will be fine.

Pushing the limits

Neil’s job was made harder by the fact that some of the amp’s quirkier ‘flaws’ were probably built into it in when it was first assembled back in 1963, when manufacturing was less stringently controlled than it is today.

The output stage does distort a lot more on this kind of Marshall amp than on a later model

“The weirdest thing was the tone controls were fitted incorrectly, in back-to-front order,” Neil recalls. “So the only thing that worked was the mid. When I got the amp going it had this huge amount of gain on the mid control - absolutely bonkers - and then nothing at all on the top and bottom. So you think, ‘Am I missing the point?’ But then I checked all the values again and eventually realised they were not in the right order.

“I’m pretty sure that was original - because I couldn’t find any evidence of it having come apart. So this particular JTM45 has always been an amp that’s had a huge midboost on it and nothing else!”

Likewise, although the swampily rich tone of the amp is a delight, some of its components are performing right at their design limits.

“The output transformer is only rated at 30 watts,” Neil says, “which is always a worry, because the amp is capable of doing 45 watts, obviously. But the fact it’s a small transformer really influences the sound.

“You’re not going to get the same amount of bottom end you’ll get off later amps, and the output stage does distort a lot more on this kind of Marshall amp than on a later model. It’s a more complex distortion - and in fact, the harmonic content of the amp is incredible.”

'Smoothing' capacitor

“This capacitor is designed to get rid of the jagged waveform that comes out of the rectifier.

“It comes out as a big triangular waveform and so this cap starts to clean it up. It’s a reservoir of charge and works in conjunction with the inductor [7] further down the amp to become a filter as well. On these early amps, these will be quite small and that again really affects the way the amp feels, the way it reacts as much as the sound.”

Output valves

“These are KT66s, the output valves, which were later exchanged for the better-known EL34s in Marshall’s amps.

“In a way, you could say the KT66 was the British counterpart of the American 6L6, and it’s certainly more comparable to a 6L6 than an EL34. KT means ‘kinkless tetrode’, and any amp fitted with KT66s would have different harmonic distortion characteristics to one fitted with EL34s. Generally, you’d say 66s are harmonically richer.”

Preamp valves

“Moving on to the preamp valves, it’s ECC83s all the way down. The first valve in line is what you call the phase-splitter, which is the valve that would be splitting the signal to drive the KT66s.

“The next one along from that powers the EQ buffering and everything else. The next one is the first actual preamp valve, which is the main gain-forming valve.”

Output transformer

“This is an RS Deluxe output transformer. These were used from the very early Marshall amps and also early Vox and Wallace amps, as well.

“This handles the signal from the big output valves, very high voltages and impedances on one side, and on the other [loudspeaker] side it’s producing very low voltages to drive the speakers in the cabinet and so on.”

'Bass' etching

Crudely hand etched ‘Bass’ probably indicates this left the Marshall line optimised for bass, not lead, although the spec difference is quite small.

Don't Miss

50 years of the Marshall stack: the birth of the 100-watt stack

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.