6 career defining records of Manu Katche

French session ace picks his finest

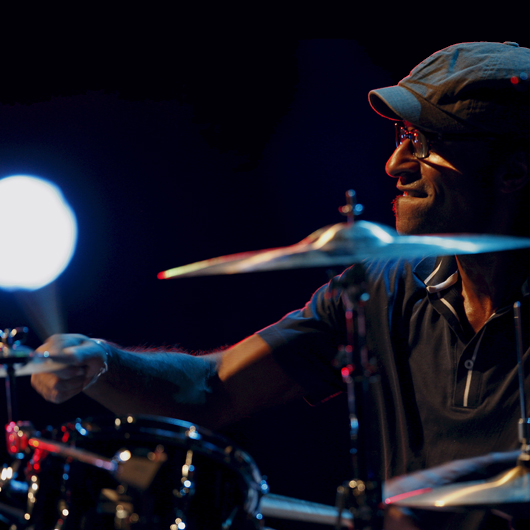

Manu Katche

French session drummer Manu Katche has brought a certain je ne sais quoi to some of rock’s biggest recordings. Here he shares the six records which have most-defined his career. telling Rhythm Magazine why they mattered so much along the way.

Next page: from Sledgehammer to Don’t Give Up...

So (1986)

Critically applauded but in need of a hit, the ex-Genesis man drafted in a crack session team to add flesh to his demos. From Sledgehammer to Don’t Give Up, Katche was on hand with the fairy dust.

Manu Katche says:

“Peter likes rock music, but he’s into African music too, so I guess the combination of my roots and the fact I’d worked on pop and rock music was why I stayed in. He just gave me the demos and told me, ‘Go ahead, find your way in’. I think he was waiting to hear something different.”

“I wasn’t competing with Phil Collins. I don’t compete with anyone. The music you make with someone has everything to do with where you are and what’s in your head. When you play a session, you’re just trying to be as good as you can with your style.”

“Peter listens to what you say, and even if he’s not sure about it he’s always willing to try. And we’d joke with him, big time. We became friends; I had an email from him two days ago, and when he comes to Paris we have lunch. I have to say, I felt musically privileged, but he’s just a regular person.”

Nothing Like The Sun (1987)

There were no stars in Katche’s eyes as the drummer hooked up with the Police legend for ping-pong, nights out in Montserrat and an organic recording experience that spawned some stone-cold classics.

Manu Katche says:

“I’d been touring and done a lot of sessions by then so I was a professional, not some little boy sat listening to Sting talking about touring the world. I knew that if he was calling me there was something he was interested in.”

“Nothing Like The Sun was easy. We recorded it in Montserrat, and had a great time. We had a swimming pool, I’d play ping-pong with Sting and we’d go out to restaurants.”

“The whole band was playing in one room, with Sting making proposals and asking questions. I think those guys know what they want to hear, but they don’t put you in that position, like, ‘OK, I’m going to test you, do this, I’m waiting’. No – we took our time. I was playing Englishman In New York and felt a reggae beat so I played it that way, and Sting loved it so we built the song up around it.”

On Every Street (1991)

The Straits’ underrated swansong was a tag-team effort between Katche and late Toto legend Jeff Porcaro, with main man Mark Knopfler encouraging each drummer to play to his weaknesses.

Manu Katche says:

“I was friends with Jeff, and we’d always say how nice it would be to share one album. I remember when we did Heavy Fuel, Mark told me he’d recorded it with Jeff but he wanted to try it again with me. I heard Jeff’s performance, and I remember saying, ‘What else do you want? This is fucking great’.”

“But he told me he wanted to try another approach. I sat behind the drums, and it’s a heavy groove, which is not very me so at first I felt awkward, but then I thought, ‘This guy has called me to play on his record, so I guess he wants my style’, which is a busy style, splashes and toms all over the kit.”

“All of a sudden, I looked up at the control room and saw Mark jumping around. Before then, [our relationship] had been a bit more difficult than with Sting and Peter, but after we recorded that track it was great – we went to the pub!”

Joe Satriani (1995)

It’s the golden rule of session drumming: never work with children, animals or guitar virtuosi. Against the odds, Katche made sure the Joe Satriani album was as memorable for the beats as for the riffs.

Manu Katche says:

“I wouldn’t describe myself as a fan of much music in that world, but I’d seen Joe live and it was, like, ‘How can that be possible?’ So when [producer] Glyn Johns called me I thought, ‘Yeah, that’s a challenge’.”

“Glyn wanted the record to be something organic; I remember arriving in San Francisco, and Glyn just saying to everyone, ‘Listen up guys – I just want takes,’ which means, first, second, third, fourth – it doesn’t matter, but he wanted a whole take from A to Z and no overdubs. So we had to have that in mind, and it wasn’t that easy, but great fun.”

“It was also hard because, of course, Joe’s music isn’t what I do regularly. I remember listening to his other albums in my hotel, and then to the demos, and trying to make a bridge between what he’d done in the past and what I was supposed to achieve. I have to say, I had more work to do in my head.”

Boys For Pele (1996)

The kooky chanteuse wanted Katche so badly that she postponed her third album until he was back from holiday. When the drummer did arrive in Cork, he found it was a tougher gig than he expected.

Manu Katche says:

“She called me at home and said, ‘I’d like you to record with me in July’. I said, ‘I always take July off with my family and I can’t let them down’. Later on I get a call from her management and they say Tori has found a solution – she’ll use click tracks and I can come in August. So I was, like, ‘Wow, she really wants me’.”

“So in August I went to Cork, and everyone was there but not playing. But the way Tori plays her piano is her way, and I’d love to have recorded with her, but this was harder because she’d already recorded the songs to a click, which meant I had to fit that while getting across the sensation that we were all together when we recorded them.”

“I really had to analyse every bar, and I remember that with some songs it took me a whole day just to feel it right, and then bring some creative parts into it.”

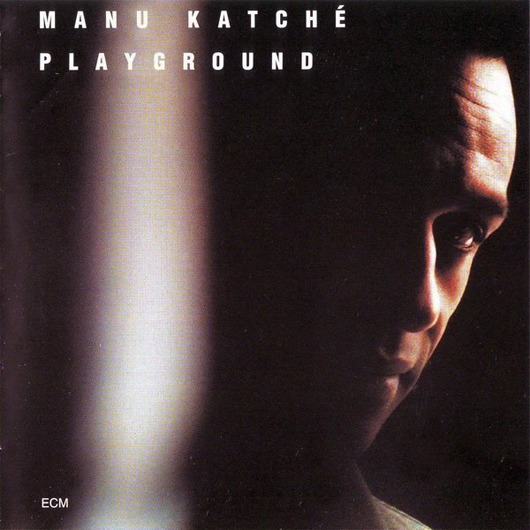

Playground (2007)

The combination of a packed session diary and his own modesty means Katche has released his self-penned albums more sporadically than most of us would like. Last year’s Playground was his best yet.

Manu Katche says:

“Even though I’ve been trained as a pianist and a classical percussionist, I was never sure if I’d be able to write, so I always kept my music at home in a little corner, until finally, after all those experiences with all those great artists, I thought, ‘OK, I should go ahead’.”

“I think Playground has been quite good in the way of writing, because I only had a year-and-a-half to do it and, when I presented it to the musicians, nobody laughed. It’s always a challenge when it’s your own music – you’re naked.”

“With my material I know every note of the structure, so when I write I try not to think about the drums. When we finally get into the studio I might not be as fresh as when I play for other artists, but I can react to the music and be a bit more inventive.”