"I drink and I smoke and I use Auto-Tune": But what's the music theory behind Charli XCX's Brat?

With multiple Grammy nominations turning Brat summer into Brat winter, we put Charli XCX's world-shakingly popular album under the musical microscope

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As soon as I listened to Brat - which is up for three Grammy Awards this weekend - I immediately liked it, but I didn’t have much context for the music.

So, I asked my online hive mind for help. Dr. Robin James recommended this Boiler Room set for Charli’s musical influences, and Lullaby77LFC suggested this Red Bull interview for broader biographical background.

We can get an insight into the production on Brat from this Tape Notes podcast with Charli and producers AG Cook and George Daniel, who also happens to be Charli’s fiancee.

They produced the album in Logic Pro and used Serum for the synths, then stemmed everything out and brought it into Pro Tools for mixing. Like a lot of producers of current pop and dance music, they think in terms of sounds more than anything else.

They talk about dialling the exact timbre of a kick drum or synth patch, and how many of Daniel’s instrumentals use a lot of vocal chops from past Charli recordings.

Cook describes going through Daniels’ tracks and muting things to create more empty space. You can tell; the finished songs are ear-grabbingly minimalist, punctuated by abrupt silences.

This idea of working by subtraction is a major difference between analogue and digital production styles. If you are recording humans playing instruments to tape, the usual method is additive.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You start with the basic tracks: guitar, bass, drums, whatever. Then you add more layers: overdubbed guitars, extra keyboards, horns, strings, backing vocals.

Producing using synths and samples in a DAW is different. You could build things up like a rock or country song, but it’s more common to work by subtraction.

Producers usually start with a bunch of loops, and then create structure by deciding when they enter and exit.

My own preferred approach is to copy and paste my loops continually across a few minutes worth of arrangement, and then create structure through deleting. It sounds like Cook uses a similar approach.

Charli and her collaborators have technical skill, but confidence is probably the main quality that separates them from less successful pop artists

It takes emotional strength to use the delete button assertively. It’s painful to work on something and then erase it! Brian Eno described liking to work subtractively way back in 1983, but he was an outlier back then. In 2024, we have a big advantage: working with analogue tape is slow and expensive, but working on the computer is fast and easy.

If you don’t like the result of deleting something, there’s always Undo. Still, even it’s practically easy to take a metaphorical machete to your music in a DAW, it still requires confidence that you are doing the right thing. Charli and her collaborators have technical skill, but confidence is probably the main quality that separates them from less successful pop artists.

The confidence aspect is especially important for singers. I learned from the Tape Notes interview that Charli comes up with vocal melodies and records them with Auto-Tune on in her headphones all the time, even if she doesn’t apply it to the final recording.

If you've never sung using real-time Auto-Tune or similar pitch correction, I recommend that you try it. Everything you do comes back into your headphones sounding perfect, so it’s impossible to sing anything “wrong”. This is highly emboldening!

Auto-Tune has made me feel less inhibited in front of the mic, and it has freed me up psychologically to try things that I otherwise wouldn’t. I have seen the same thing happen for other singers too.

Rick Beato thinks Auto-Tune has 'destroyed popular music'. Here's why he's wrong

Charli laments that Auto-Tune has made her lazy about her pitch control, but that is probably a worthwhile tradeoff for the confidence it gives her. She sums up her studio ethos: “I drink and I smoke and I use Auto-Tune.”

This may sound unprofessional, but you can’t sound like she does without bringing a party atmosphere to the usually cold and clinical environment of the studio. There are few musical experiences more unnerving than having a microphone in front of you, knowing that your voice is going to be scrutinized endlessly until the end of time. Anything you can do to feel relaxed and centered is a help.

Anyway, given the quantity and quality of her output, I’m sure that Charli is more disciplined and businesslike in the studio than she lets on.

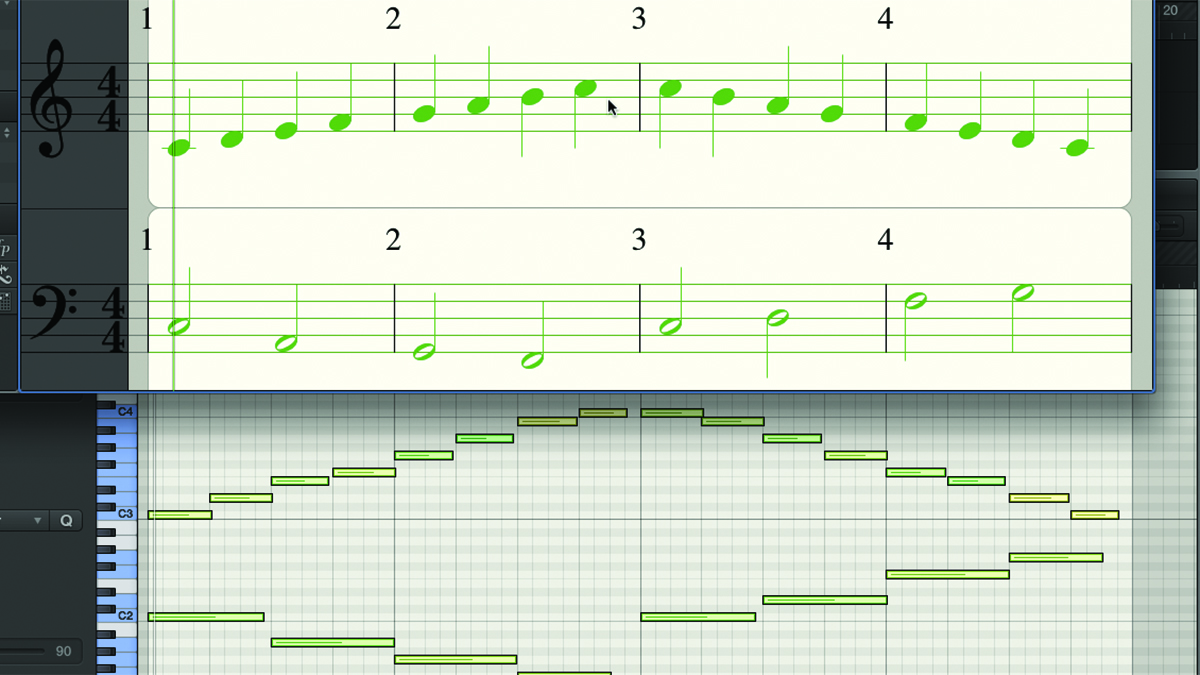

The one aspect of the songs that Charli, Cook and Daniels do not talk much about is the “notes on the page” side of things, their choices of pitches and rhythms. I put “notes on the page” in scare quotes because there is almost certainly nothing in these songs being written down on paper; they probably improvise everything straight into the computer and then edit from there.

It would be nice to know more about their approach to melodies and harmonies, but that’s okay, we can figure those things out from listening.

There are three songs on Brat that grab me in particular. The first is “360”, the leadoff track and second single after “Von Dutch.” While “Von Dutch” is abrasive and confrontational, “360” feels more playful. It’s the song that my kids like the most (though parents should beware of one F-bomb), and it’s the one I’d be most inclined to play at a party.

The rhythm from the intro fakes you out in a charming way.

Even if you can’t read notation, you might be able to tell what’s happening just from looking at the note patterns. The first little pattern with the high note at the end repeats three times.

This makes you expect it a fourth time too, but no. Instead of the first note in the pattern, there’s a hole, a silence. Then a new pattern plays. Aside from that first note missing, it’s the same rhythm as before, but that first note was the anchor, the foundation of the structure, and without it, you’re left disoriented. Even though I have listened to the song many times now and know the gap is coming, it still wrong-foots me.

The intro riff doesn’t just fake you out rhythmically, it’s harmonically ambiguous too. The first two notes are B and C, which a lifetime of enculturation has taught you to hear as the leading tone and tonic in the key of C major. The E underneath reinforces that idea. But then there’s an immediate E to F, the leading tone and tonic in the key of F major.

Then there’s a jump up to C, and then up even further to A. So wait, maybe we were in A minor this whole time? Or still F major? The last little phrase is more clearly in A minor, until it jumps up to land on C, so, uh, actually we were really in C major all along? It seems designed to keep you guessing.

You might be imagining an earnest piano ballad, but no, it sounds just as much like dystopian sci-fi dance music as the rest of the album

My editor was struck hardest by “I Think About It All The Time”, and I can see why. When I think of Charli XCX, I think of partying and hedonism. I was certainly not expecting a song about Charli meeting her friend Noonie Bao’s new baby, leading her to a sober reflection on whether to try to have kids herself.

I can only imagine the conflicting pressures that Charli must be facing as a successful young woman in the entertainment world. The comedian Taylor Tomlinson sums it up: “I’d like to have kids, too, which is a shame, because I’m so talented.” Charli’s delivery has some of that same deadpan humor overlaying what must be big feelings.

Anyway, if you read my description of the song without listening to the track, you might be imagining an earnest piano ballad, but no, it sounds just as much like dystopian sci-fi dance music as the rest of the album. Charli’s voice doesn’t have its usual processing and distortion, but the synth sound continues to be harsh, and it changes dramatically on every chord.

The chords themselves are simple in concept, but voiced very strangely, and together with the constantly shifting timbre, they make for a surreal listening experience.

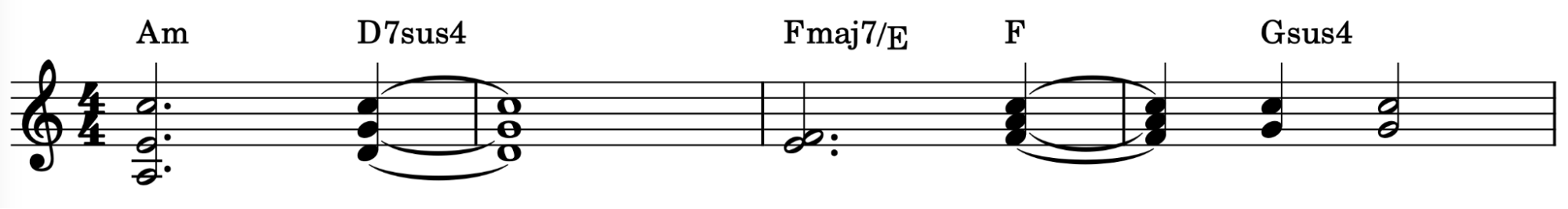

The first chord is Am, spaced widely. The second is an ambiguous stack of fourths: D, G and C. You could call it D7sus4, or Gsus4/D. The third chord is just two notes, E and F. They form a minor second, the most dissonant possible interval in the Western tuning system. It’s followed by a regular F major triad, so from context, you could retroactively hear the two-note chord as a particularly bleak voicing of Fmaj7/E. Finally, there’s another ambiguous open fourth, G and C, which I hear as Gsus4.

And what about that always-morphing synth sound? I would have naively guessed that they used a different setting for every chord. However, the synth designer and sound design wizard Francis Prève set me straight with the below explanation.

“Start with a waveform that's bright enough to be processed via one of Serum's formant filters. I used a sawtooth, which is too bright, but we'll get to that. Select one of the Formant filters. They all create this effect. Serum has a very cool Matrix modulation tool called NoteOn Rand. I applied this to the cutoff, so that every time you play a new chord, the cutoff changes randomly. For more control, use Velocity and tinker with the MIDI.

“Since the result is too bright, put a filter at the top of Serum's FX chain. I tried both lowpass and bandpass and working quickly, ended up with a 6db lowpass. Finally, for the bit-crushing, we add the Distortion effect to the end of the FX chain. Here, it's set to Downsample mode. Adjust the aliasing to taste, then use the Mix wet/dry to dial it back.”

Francis should know! If you have used a preset in a software synth, there’s a solid chance that he designed it.

My own favorite song on Brat is “Sympathy is a Knife”. Fans speculate that it’s about Charli’s insecurities about Taylor Swift. The line about not wanting to see this person backstage at her boyfriend’s show would seem to support the idea. Charli’s fiance and producer George Daniel is the drummer of The 1975, and during Brat’s production, Swift was dating the band’s frontman, Matty Healy.

I do not have a lot of emotional investment in this question, but the an theory would make sense. I mean, what pop singer wouldn’t feel insecure in a room with Taylor Swift? Maybe Beyoncé?

My wife Anna, who is not much of a pop head but who does love Björk, says that “Sympathy is a Knife” is the one Charli song that really appeals to her. I don’t know whether Charli was trying to sound like Björk here, but she is a fan (and apparently the feeling is mutual.) I can hear the connection in the distorted vocals and drums, the non-rhyming lyrics, and especially the exotic modality.

The track starts with thirty seconds of both the synth and vocal melody hammering E-flat and G relentlessly, so you’re thinking, okay, key of E-flat major. You don’t usually hear distorted synth grooves in major keys, but sure. And then the chorus hits, and while the bass enters on E-flat as expected, the melody hits a big A. That note is not in the key of E-flat! It’s the sharp fourth, and it resolves up to B-flat, the fifth. So maybe the song is in E-flat Lydian mode?

That’s something you hear in film scores, not electronic dance songs… unless they are by Björk.

The rest of the chorus moves to Gm, then F, then Bb. On the page, this would suggest that the song is actually in B-flat major, and that whole buildup on E-flat was implying the IV chord. But the sense of B-flat major as the key is weak too. The Bb chord only happens for two beats at the end of each phrase and it has its third D rather than its root B-flat underneath it, which makes it feel less like a destination.

10 music theory tricks every producer and songwriter should know

The high-pitched string synth pedals a B-flat over the entire chorus, but while that might stabilize the key, it directly fights the F chords in the third and seventh bars. Charli is singing A on each of those chords, which you’d expect on an F chord, but that is a tense rub against B-flat. The harmony and production work together to suggest a person struggling to hold it together emotionally.

I want to point to two specific moments in the track that I love. One is the gap halfway through the chorus at 0:47. Like I said above, Charli and her producers love to use unexpected silence as a way to get your attention. You’re expecting a big pounding downbeat here, and instead, all you get are some fluttery little handclaps.

The other production touch that leaps out at me is the “kn-kn-kn-kn-knife” stutter at 2:22. This is such an easy effect to do in Logic or any other DAW, just select a sixteenth note’s worth of the vocal track, and then copy and paste a few times. But just because it probably took five seconds to do, doesn’t mean that it wasn’t an excellent idea.

Ethan Hein has a PhD in music education from New York University. He teaches music education, technology, theory and songwriting at NYU, The New School, Montclair State University, and Western Illinois University. As a founding member of the NYU Music Experience Design Lab, Ethan has taken a leadership role in the development of online tools for music learning and expression, most notably the Groove Pizza. Together with Will Kuhn, he is the co-author of Electronic Music School: a Contemporary Approach to Teaching Musical Creativity, published in 2021 by Oxford University Press. Read his full CV here.