Apashe: "Ableton became a reason to give up on your old DAW and switch - now Bitwig is starting to get that same traction"

Best of 2023: Blending the world of classical music with a hard-hitting, electronic ethos, Apashe is operating within a uniquely epic sonic universe. We find out more about the scope of his ambitions

Join us for our traditional look back at the news and features that floated your boat this year.

Best of 2023: “I’ve done just a tiny percentage of what he’s been through, but I’ve not got a Tim Burton friend who’s asked me to score 50 movies for him yet.” Apashe – real name John De Buck – is sharing with us his love of legendary cinematic maestro Danny Elfman; both an inspiration to the Belgium-born Canadian genre-blending musician, and his idea of a dream collaborator.

“He’s kind of like me. I feel like he’s also done that switch from being in a band and making mostly pop-rock music and then Tim Burton hit him up to score music for movies. Now he’s writing pieces for classical music. That really sparked my interest. That’s both what I want to do and kind of what’s happened to me already. I wish to be like him, one day.”

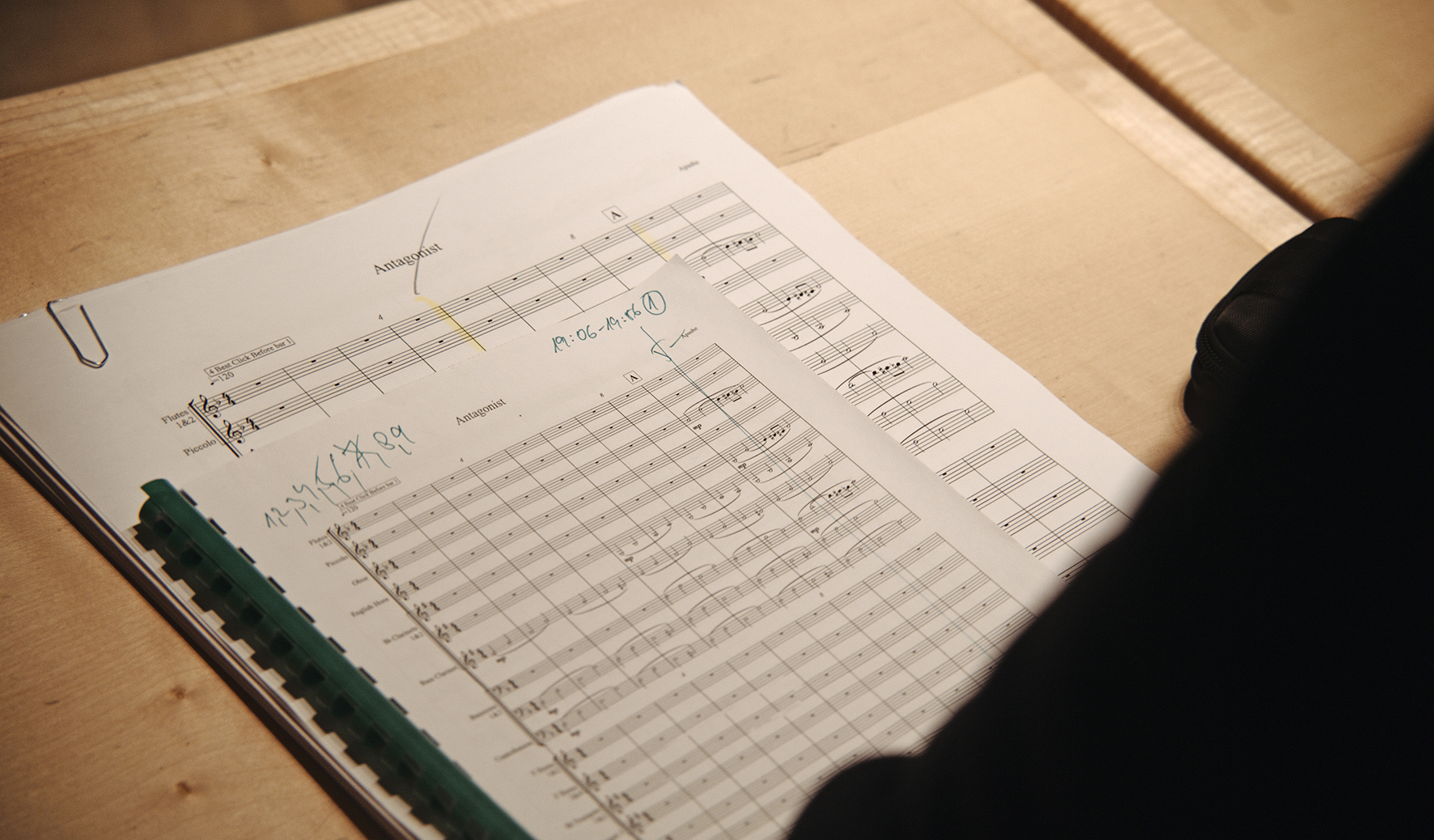

We’re speaking to Apashe during the mixing process of his new album Antagonist, the follow-up to 2020’s Renaissance – wherein the style-mashing polymath enlisted the Prague Philharmonic Orchestra to take his emotive and intense electronic tracks and expand their sound into the realms of the hyper-cinematic. Antagonist continues the journey, adding the Bulgarian Symphony Orchestra and a children’s choir into the mix.

“It’s definitely easier because I know what I’m doing a little better,” explains John. “For Renaissance it was almost like jumping into the unknown. I didn’t know what was possible and what was really complicated to write. What can you ask of an orchestra and where’s the room between the two spaces? All the small little details I didn’t quite know. So now it’s more complicated because I know there’s more room. Now the question is how do I make that work.”

Turning up

John’s route into music came while studying electroacoustics at Concordia University. From there, his career developed into a stint at Apollo Studios in Montreal, where he worked as a co-producer on the sound design for numerous video games. In 2014 he embarked on his own artist career. With his recent settling into an electronic-meets-classical hybrid style, we wonder where his interest in this fusion began?

“It was a journey because originally – as a teenager – I was just sampling classical music because I loved it. It all kind of started from that point in time. I just love taking really old recordings and trying to make something new out of them. I’ve always been a fan of sampling culture, and then after a while you kind of realise that everything has been sampled, everything has been eaten up and chewed a million times. It’s hard to make something original. Then it was around the same time that I went to university to study music and it was there that I learned about orchestration.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“[At university] I got into film music and then music for advertising. I was learning all these different things, and trying to play with different instruments. I loved all of that and it was nice when, for example, [when freelance trailer-scoring] a client wanted an orchestra, you could use something like a Kontakt instrument and then play around with it.”

Though John began using orchestral sample libraries, such as those designed by Spitfire and Orchestral Tools, he began to be irked by a perceived lack of realism. “At the end of the day, some of them work and some don’t. I love those libraries but it came to a point where I wasn’t getting a certain tone from samples that I like. I wondered if I needed to print it on vinyl then record it and destroy it? I didn’t really know how to get the tone I liked.”

It was at this point that John began to look for smaller ensembles that he could record, before sampling (and muddying to taste) later. “For Renaissance we did the first symphonic orchestra with the Prague Philharmonic. I had a lot of fun composing and having that back and forth with the arranger.”

But recording the orchestra wasn’t always enough; John wanted to get his hands dirty with the finished stems. “Getting the stems and destroying the recordings was fun. Sampling yourself means you can directly do what you want or what you need. This new album Antagonist is my second try at composing for an orchestra and then sampling it.”

Revenge of the orchestra

John points out that, in terms of similarities, electronic music and classic forms really have very little in common; “Electronic music is a lot more repetitive and is often more really created for dance purposes. It’s loud and compressed. Classical music can’t really be as repetitive or loud, and you can’t compress those classical instruments really because they’d just sound really bad. They’re almost the polar opposite in a lot of ways.”

Listening to some of the new record’s (in production at time of writing), tracks such as the epic Gasoline (which features Delhi-based hip-hop artist Raga), the incendiary Revenge of the Orchestra, the intense, choir-dominated Rise at Nightfall and the bouncing Hasselhoff, we’re blown away at the scale and complexity of the arrangements. We wonder if John sections these arrangements to make space for the more classical moments?

“I don’t necessarily put the arrangements into ‘sections’, but I like to keep the old sampling ethos of trial and error. I’ll really feel that section that I composed for the orchestra then I’ll decide what I do with it. How can I chop it? How can I effect it and re-use it? So, sometimes it works, sometimes it’s difficult. I wouldn’t say it’s easy all the time but it’s definitely an infinite source of inspiration. For me it’s pretty easy. If it went through the filter of being recorded already, that’s because I like it and if I can’t chop it up or sample it too much then I’ll keep it as is.”

We ask more about a few of the tracks we’ve highlighted. Firstly, we’re staggered to learn that the massive, hellish choir in Rise at Nightfall is software-based. “The choir there is fake at the moment. When the symphonic orchestra is real it gives you leeway to sprinkle some software on there, it sounds really real though. That one is pretty straightforward. It was just a recording of the orchestra with that on top, there hasn’t been any sampling on top of that one yet.

“We’re recording with a choir in two weeks, but not for this track; I actually kind of like how the software choir sounds in this there as it is. I find software choirs work well when it’s sustained notes, and it’s kind of ‘big’. As soon as you want tricky details, words and vocalisations then it’s a lot more difficult, but for that kind of use, it’s actually quite good.”

With all of these classically-disciplined musicians to command, we correctly assume that John reads and writes sheet music. “I read music enough to ping-pong with my collaborators. I work in Sibelius,” John explains. “I did two years of orchestration study at university, so I do read music and I used to work in Finale [at university] so I can use multiple programs for notation.

“Now I work with an orchestrator, Frederic Begin, who I get to write straight partitions (sheet music per-instrument). When you write for 65 instruments, it becomes a whole different job. I don’t even know any composer who does their partitions themselves. It’s a job in itself.”

John describes in detail his demoing process, and shares that most of his demos have placeholder string sounds via Kontakt and Orchestral Tools’ libraries. “Basically I send Frederic all MIDI stuff and then we bounce back the Sibelius files. I mostly re-touch articulations because the rest is always kind of good. He really copies my demos and the difficult part is that I want the recordings to sound like anything but my demos. They’re made in the box so I try to go as far as I can from there. But that’s his reference point. He always has the best suggestions to bring life to my compositions.”

Boxed in

John tells us that though most of the sessions for Antagonist were recorded into Pro Tools, he likes to mix using Ableton Live. “I prefer mixing while I compose, I do that easily in Ableton Live. It’s too much of a pain to stem things out and put it back in. I only really like Pro Tools for recording elements. It’s been a few years but my Pro Tools shortcut skills are getting slow now.”

Apashe is something of an Ableton aficionado, but he’s recognising similar momentum over at Bitwig. “I feel like more people are drifting towards Live, and Bitwig is also attracting new people. Ableton started in a similar place to where Bitwig is now. Ableton became a reason to give up on your old DAW and switch, and Bitwig is starting to get that same traction.”

Our guide to the internet's biggest collection of free effects plugins, the MFreeFXBundle

Within his Live-based setup is a pickle-tray of familiar mix plugins: “I’m all the way in the box. The only thing I use that’s not in the box is when I’m going to record some synths. It’s all toys for me that I play with. It’s either fully instruments or in-the-box. I’m starting to use more Live plugins, otherwise I’m digging into the Melda Production bundle, I use iZotope. Because I’m old-school I still use Waves a lot for things like vocals.

“For mixing, aside from the Melda, I’ve been using Oeksound Spiff and Soothe a lot for creative stuff. Soothe I’ve been using to remove all the resonance from stuff, it’s more creative mixing type stuff. Otherwise I still used a lot of UAD plugins. One I surprisingly like is ’bx_subsynth’; it just creates a nice sub underneath. In my mixing folder it’s just all the Waves stuff. The rest is mainly Ableton stuff, or effects.”

On the effects front, iZotope’s Trash 2 has been one of John’s regular go-tos for years, but he hungers for an upgrade; “I feel like it’s time for them to bring out Trash 3 at this point,” John laughs. “Also, I must mention CLA from Waves, then a bunch of racks from Ableton. I really like RC 24 and 48 – two reverbs from Native Instruments. I used to use a lot of Native Instruments’ stuff but I kind of stopped.

“I use Melodyne a lot for my stems, but that’s less of an effect and is more of a tool. Then two of my favourites that really helped with giving some tracks the ‘sample’ tone was Ocean Way Studios from UAD. It emulates a beautiful room, it makes for a superb sampling tone. Otherwise the EMT 140 which is another plate reverb.”

Bring the beef

As mentioned, Brainworx’ bx_subsynth is a regular feature of Apashe’s low-end processing chains, although for most of his tracks, the low-end is generated from hardware synths. “I used to like plugins like [Waves] Renaissance Bass,” John explains, “but that was just taking the sample and pitching it down to create that low end. Bx_subsynth creates a synth out of it that follows it.

The ultimate guide to sub bass: tips and tricks for a high-class low-end

“It’s mostly just for when something’s thin: I will do that and then put some harmonics on it and then still remove the low end. It’s just to kind of beef it up. It’s a tool to create content that’s not there originally in a sample. I find it really useful. At the end of the day, when you do that, you end up kind of cutting it out quite a bit, just because there will be another proper synth somewhere in the song and I don’t want it to clash.”

Every second counts

A standout track, Hasselhoff, features a guest appearance from Estonian rapper Tommy Cash. We ask how this pairing came together? “So I was on tour in Tallinn, Estonia,” explains John, “and he DM’d me asking if I wanted to hit the studio. That was the starting point. We’d already said that we’d work on something together but nothing concrete came out of it until I was in his city and I didn’t know he was living there. He showed me a bunch of songs that he was working on, that was one of them. I basically took it from there and did the version for the album.

“There is still a whole part that I want to re-record. I want to record a trombone solo in there too. His demo was very hip-hop, it had like 808 and chords. It was kind of like a bit of a loop, but it was really moody. I chose that one because I felt the potential of it.”

John explains that the songs for this second symphonic epic came together fairly briskly: “It does double the work when you have to record it with a symphonic orchestra, you need to do the song and then you need to make a demo for the orchestra and then partitions for all of the parts, then put it all back in the original demo. It’s longer than just mixing a standard track by yourself.

“I think the fastest was probably the track Lost in Mumbai, then Hasselhoff came together pretty quick. The one that is taking a while now is Human. That track was originally a pitch for the Fast and Furious trailer and then I had to make modifications for them.

“Then for like nine months they gave no update, so I thought they weren’t going to use it; so I made a new version of it for me, and then they came back and said they were going to use it. Then, they wanted a few changes to suit their needs. I found an in-between version of what they wanted and my new version. Now, I’m changing just a bunch of things because we’re doing a video on it, and I want it to kind of fit.”

On the trailer-scoring front (something of which John has years of experience) we wonder what approaches demonstrably work when handling new briefs? “I guess just be fast! That’s the only real skill you need. So many people are competent musicians and could do it – but the real difference is just being able to adjust and turn things around quickly. Being called two days prior to a deadline and being asked to make something is commonplace. That was the case for Human [the Fast and Furious track]. I had 48 hours, including writing with a rapper and everything, so it was all really really quick.”

Keeping connected

We ask Apashe whether, while focusing on big projects like this, he has time to just be spontaneously creative and think about other tracks outside the world of the record: “I’m constantly working on other stuff, I feel like it helps to just step back from tracks. When you’re stuck in there you can get lost. It’s hard to make conscious choices about whether or not you like it. There are so many possibilities with every song, so many avenues you can take it down.

“For me, I need to kind of step out of it then come back later. I really like to sleep on songs. Often when you work on it a lot you don’t really feel it anymore. That’s not necessarily because it’s bad. If you reopen it two weeks later when you’ve kind of forgotten about it and you still feel it, then you know it’s worth finishing.”

When it comes to mixing, it’s important for John to listen closely, but that can lead to its own problems: “I love mixing but I sometimes hate the process because you’re so disconnected from the song. You’re just obsessed with tiny details, and how every sound fits.”

With the album imminent and a 29-date US tour looming on the horizon, Apashe’s name is in the ascendancy. We wonder what advice he’d give to anyone looking to get a foothold today? “It just depends on why you want to start. Do you want to start a career or just make music because you like making music? It’s often two different things that I see across all the people that I meet. You will have people who want to do it as a job and want to be up on stage.

“Then you have people who make music because they’ve always made music and that’s what they like. Then it just happened that they can make a living out of it, so they work to make that happen. I’d always encourage people to make music regardless of their career ambitions. It’s becoming easier and easier. If you want to listen to yourself. It’s never been as easy as it is now, and it’s only going to get easier."

Apashe's Antagonist will be released to coincide with a 29-date US tour this Autumn.

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.