5 Dimebag Darrell Pantera songs guitarists need to hear

A true original

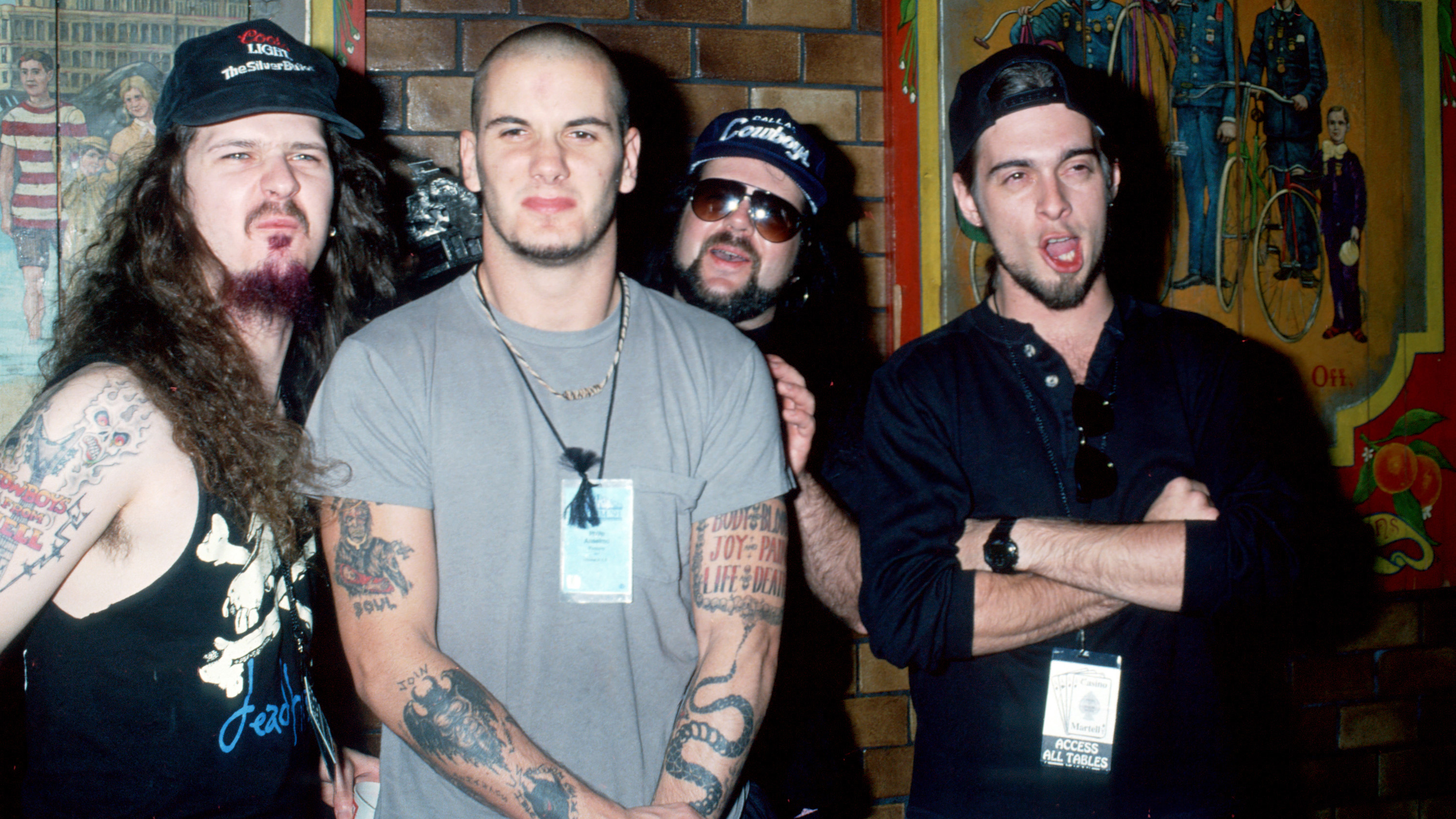

Dimebag Darrell’s approach to heavy metal guitar playing was a typically Texan go-big-or-go-home reach for new extremes, as Zakk Wylde is now finding as he gets to grips with his tone and parts ahead of Pantera tribute shows. It was a celebration of all who had gone before him – KISS, Van Halen, Black Sabbath and Judas Priest – but once interpreted through his own virtuosity, those influences soon hardened into something else. Something new.

Forming Pantera with his brother, Vinnie Paul, in 1981, a coltish Darrell Lance Abbott soon recognised the power of a stage name, choosing Diamond Darrell (another KISS reference), and set about workshopping his chops in an era that is considered off-brand for many of the band’s followers. Back then, in the early 80s, Pantera played good-times glam metal. But we shouldn’t cast those early releases off; the transition from Metal Magic through Projects In The Jungle, I Am The Night and the Phil Anselmo-fronted Power Metal (1988) showed the direction of travel.

Come 1990, when they hit Pantego Sound Studio, Texas, in the company of producer Terry Date, they had a Year Zero moment for their sound – more steel, zero glam. Cowboys From Hell was heavier, a self-styled “power groove” album, with power groove a designation to acknowledge the proficiency of Paul and bassist Rex Brown’s rhythm section to lock in with Dimebag’s uncompromising riffs for a different kind of metal, tight as a drum but with a boogie-woogie swagger that was beyond their tight-hipped contemporaries. Subsequent releases would only get more extreme, more atonal, with effects such as the DigiTech Whammy on-hand for such times when it was more appropriate to reference the animal kingdom than Randy Rhoads or Eddie Van Halen.

Speaking of Eddie Van Halen. His death and the tributes that followed only go to show once more how much Dimebag Darrell is missed. As a disciple of Van Halen, one who deployed many of the same scalar patterns in his solos, Dimebag’s perspective on Eddie’s legacy would have been welcome, and so too his playing, which in a sense was a tribute to Van Halen. He took a similar approach to the electric guitar, bending the rules, ping-ponging between the expressive potential of virtuosity and the good, clean fun of guitar noise.

Not since Van Halen has there been a hard rock or metal guitarist with a profile like Dimebag, a player whose instincts for rhythm and lead alike were all id – ferocious, ripping, exhilarating. Even his bourbon-and-Coke diplomacy somehow presented him as a quasi-presidential master of ceremonies, the Pope of contemporary metal guitar high jinks and misadventure. We could do with a little of that colour today.

1. Cemetery Gates – (Cowboys From Hell, 1990)

Pantera’s debut for ATCO Records is seen by many as their debut proper. It was a paradigm shift for heavy metal, drawing on the intensity of Slayer and marrying it to B-movie heavy metal steel for a sound like no other. We could have put the title track here, the signature jam, but the stateliness and grandeur of Cemetery Gates offers the perfect showcase for Dimebag’s impeccable note choice and phrasing – made all the more dramatic when his lead playing enters the aerobic zone with legato runs and fast-picked sections, or when he leans into those big harmonic squeals to play call-and-response with Anselmo’s Halford-esque screams.

The arrangements were audacious

And what about that guitar tone? Again, unique. If Metallica were waging war on the mids at the time, it was Dimebag who nuked them, using a Furman PQ-3 (and also a PQ-4 and MXR 6-band EQ pedal) to wipe them out and bring a razor’s edge to his chug. A rack-mounted MXR Flanger/Doubler was his always-on effect. His backline was different, preferring a solid-state Randall RG 100ES and running it through a Randall 412JB. Dimebag’s rationale for a transistorised amp over tubes? There was enough warmth in his tone, and he needed something more industrial and visceral.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

That alien and inhospitable rhythm tone is present and correct in Cemetery Gates, and yet it translates in what would be Pantera’s last conventional metal power ballad. Reportedly he used a Roland Jazz Chorus for the cleans. The whole thing is regal. The arrangements were audacious, as though Dimebag was K.K. Downing and Glenn Tipton.

2. Walk – (A Vulgar Display Of Power, 1992)

Pantera’s magnum opus doubles down on the gravel-scrape chug of Cowboys From Hell, with Dimebag’s inhuman buzzsaw rhythm tone sounding like it was on 10 no matter how low you turn the stereo down. Cowboys From Hell might be the one they played when metaphorically handing out business cards at the end of the show – like Zorro marking his victims with a “Z” – but Walk is the quintessential Pantera anthem, an almost monotone riff tuned just below D, performed in a 12/8 shuffle, super aggro, with a show-stopping solo that’s engineered to groove along with the song.

If the riff is easy to play, it’s hard to perfect. You need an index finger like Hulk Hogan’s thigh to get the bend just right and in time. The solo is hard to play, nigh-on impossible to perfect. To hear a cover version of it is to hear distance, the acreage that exists between Dimebag’s ability and lived-in relationship with his style and the pretenders riding on his coat-tails.

After A Vulgar Display Of Power, dozens of bands tried to go “power groove,” to dial up the intensity and soundtrack the mosh-pit. None got close. It’s like trying to beat the Stones at their own game; just as you’re not going to write a better rock ’n’ roll song than Jumpin’ Jack Flash, you’re not going to get close to the double-jointed mechanics of Walk.

3. This Love – (A Vulgar Display Of Power, 1992)

The transitions are smoother than Cary Grant after two martinis

What a strange deployment of a I-IV-V progression. This Love is haunting, sinister, brooding… It sounds like a metal ballad as written by the Boston Strangler, but it’s another textbook lesson Dimebag’s feel for dynamics. Once more, he’s taking that progression from the blues and using it in an alien context, this time with clean, modulated arpeggios that resolve just in time to switch channels and explode in a roman candle of gain and, well, Phil Anselmo.

The transitions are smoother than Cary Grant after two martinis, with an effortless sense of melodicism and feel taking some of the heat and muscle out of the song before preparing to ratchet up the tension in the verse. Then you have two of the best riffs in the Dimebag canon to close the song out; the first is a groovy headbang, the second a Debbie Downer doom-chug, misery laced with tension. You need a shower after listening to This Love. It takes the air out of the room.

4. Becoming – (Far Beyond Driven, 1994)

A pitchshifting effect on a treadle? Perfect

Far Beyond Driven was a sound unto itself. It was everything that had gone before, only louder, harsher. The aggression that informed A Vulgar Display Of Power was here in spades, occasionally spoiling for a sour, confrontational atmosphere. Gear-wise, much of the game was the same. He was using a Randall Century 200 head by now but it was still solid-state, still dimed when it came to the gain, and the weapon of choice was his Dean ML Series guitars.

Again, he used his 1981 “Dean from Hell” blue lightning graphic model whenever in standard tuning and a Tobacco Sunburst model when down in D. The Bill Lawrence L-500L blade humbucker offered the right blend of piss and vinegar at the bridge position. What makes Becoming essential listening, however, is the use of the DigiTech Whammy. A pitchshifting effect on a treadle? Perfect. What could be better for a guitarist weaned on harmonic squeals and double-locking Floyd Rose vibrato?

Now, many players have used the DigiTech Whammy, and few use it for subtlety, yet none have found the sweet spot of pure animalism as Dimebag does here. Becoming sees a down-tuned chug riff erupt in a squawk that is either feline or avian, depending on which veterinarian you ask.

The verse riff could be seen as the The Fly II to Walk’s The Fly, mutated beyond recognition but with the same DNA, and when it gives way to the chorus and then the solo, that’s when it’s time to step back on the new toy… After performing the magic trick of making an ear-worm of inhospitable ingredients, Dimebag earns the right to take the guitar solo into the pig pen with the yowling skronk of the solo.

5. Floods – (The Great Southern Trendkill, 1996)

Not only is it a great example of the band’s chemistry, with Brown – an excellent bassist – enjoying his finest hour, it features one of Dimebag’s finest solos

Pantera’s high-functioning dysfunction entered a new phase by the mid-90s. Anselmo’s aggression had settled into nihilism, his back injury taking him through a diet of painkillers and grog, and eventually heroin. This junk-sick pallor is all over The Great Southern Trendkill.

Later in the year, Anselmo would overdose and die for a couple of minutes before being revived. While this context has little to do with the guitar playing, it is necessary when considering the choices made on this record, such as the Whammy pedal scream-a-thon thrasher Suicide Note Pt II, and the near total aversion to levity. The ability, or the intention, to take a work of bruising physicality and make it as catchy as Karma Chameleon had gone. That’s not to say it didn’t work on record. The breadcrumb trail was always leading somewhere more sinister.

Classic interview: Dimebag Darrell, July 1994

Perhaps that is what makes Floods stand out. It’s a rare moment of beauty on an ugly album, yet it’s despondent feel is of a piece with the moment. Not only is it a great example of the band’s chemistry, with Brown – an excellent bassist – enjoying his finest hour, it features one of Dimebag’s finest solos.

It was a long time in the works. He had those solo parts in the mid-80s, and they exhibit the Rhoads influence, the intrusion of classical music’s discipline and grandeur into a contemporary pop subculture. By now a calling card, the Whammy makes an appearance, but it’s the melodicism in the solo that grants this discordant sore of an album a rare moment of grace, perfectly executed.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.