Why the kick, snare and clap are the core elements of a beat

Forget the ghost notes and ambient textures - your ‘core’ drum hits make or break a beat. Let’s make them shine…

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In four-to-the-floor electronic genres, the bass drum is king. Every producer is searching for that single perfect kick sound that will magically transform an average track into a club-clobbering behemoth.

Meanwhile, in styles such as hip-hop and drum & bass, the snare is just as important, providing that one-two punch in conjunction with the kick to help the groove pound home under a domineering bassline.

Then there’s the clap: whether it’s the recorded sound of humans hitting their hands together or a synthetic equivalent, it’s a percussive sound that cracks, sizzles and repeats throughout clubs the world over.

No matter whether you’re a fan of acoustic tunes or pumpin’ electronic tracks, some sort of drum kit always provides the rhythmic bedrock upon which everything else is based. A drum groove’s complexity varies wildly from track to track, but the programming principles and general sounds used are pretty much universal across the board.

The acoustic drum kit’s star performer is the bass (or kick) drum: a large, floor-positioned drum played using a foot pedal-triggered beater. Defined by its initial click followed by a booming resonant tail, this low-pitched sound – tuned to a specific harmonic or inharmonic pitch – is used to hammer out the basic rhythmic component of a beat. One note is almost always played on the downbeat, and four-to-the-floor styles are defined by the use of a kick note on – yep, you guessed it – every beat of the bar.

The acoustic kit’s snare drum is usually beaten with a stick, and is played along with the bass drum – most commonly on beats two and four of each bar – to provide a solid one-two punch that not only keeps time, but acts as the foundation for the other kit elements. A drummer may also pepper quieter, syncopated snare notes in and out of the main beat to provide groove and swing.

The clap is a percussive sound we’re all familiar with, created by a human slapping their palms together. It is generally an ancillary percussive instrument when used along with an acoustic kit, but has taken on a life of its own in the dance music realm thanks to the inclusion of noise-based clap synthesis.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Speaking of dance music, the development of synthesis- and sample-based drum machines (and, more recently, the use of one-shot samples and loops) has changed the rhythmic landscape of modern music. Drum kit elements are emulated with synthesiser circuits, samples, or a combo of the two. For example, many electronic bass drums are built from a synthesised ‘boom’ combined with a sample-based attack to replicate the beater’s click, while snares and claps are made from synthetic white noise.

Aside from the kick drum, snare drum and clap, a typical drum kit comprises other instruments: metal hi-hats/cymbals, toms and other percussion. While these accompanying sounds generally bring the most groove, it’s those foundational elements that will make or break the sonic success of a beat, which is why we’re going to focus on these three core elements over the next few pages by showing you how to design pro-quality kicks, snares and claps fit for any electronic production.

Back to basics

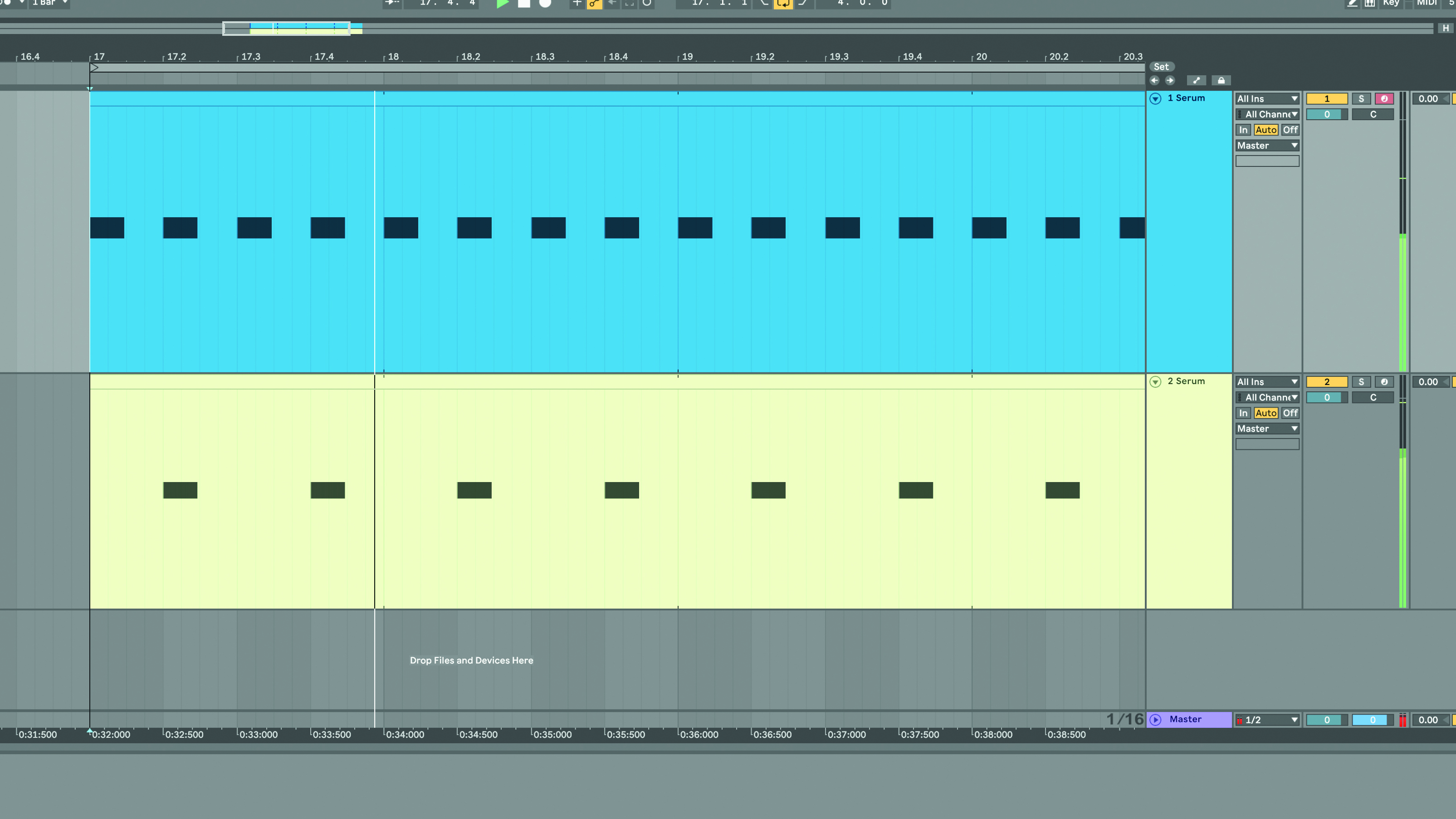

For a newcomer to electronic music production, it’s best to keep things simple: arm yourself with a collection of high-quality one-shot samples, then lay them out as audio on your DAW’s timeline, or replay the samples via a MIDI-triggered drum sampler. Many of these sounds have been created by world-class sound designers, so using prefab samples is the most logical way to go if you’re keen to lay down half-decent tracks without getting bogged down in complex drum design. In fact, this is still the chosen method for many top producers: simply pick the right drum samples from the start!

However, once you move past the beginner stage, there are many reasons to explore the world of drum design, synthesis and layering. For one, you’ll be able to craft beats that are unique to only you, helping give you a signature sound. Secondly, you’ll have the ability to tweak and refine your drums to precisely fit the other elements in a track, giving you microscopic control over every component in a mix. And thirdly, the process of building beats from scratch is a fantastic way to understand drum science and sound synthesis – in other words, it’s the ultimate in geeked-out fun!

Pitch and noise

Drums are short in duration, but pack in a fair amount of detail over that short space of time. The basis of drum synthesis involves manipulating a waveform’s pitch response: call up a basic waveform in a synth, which will have a flat, tuned pitch; then sweep this pitch from high to low over the course of a few milliseconds. This downwards-sweeping ‘boom’ will create a bass drum-like tone at lower pitches, or the body of a snare or tom at higher pitches.

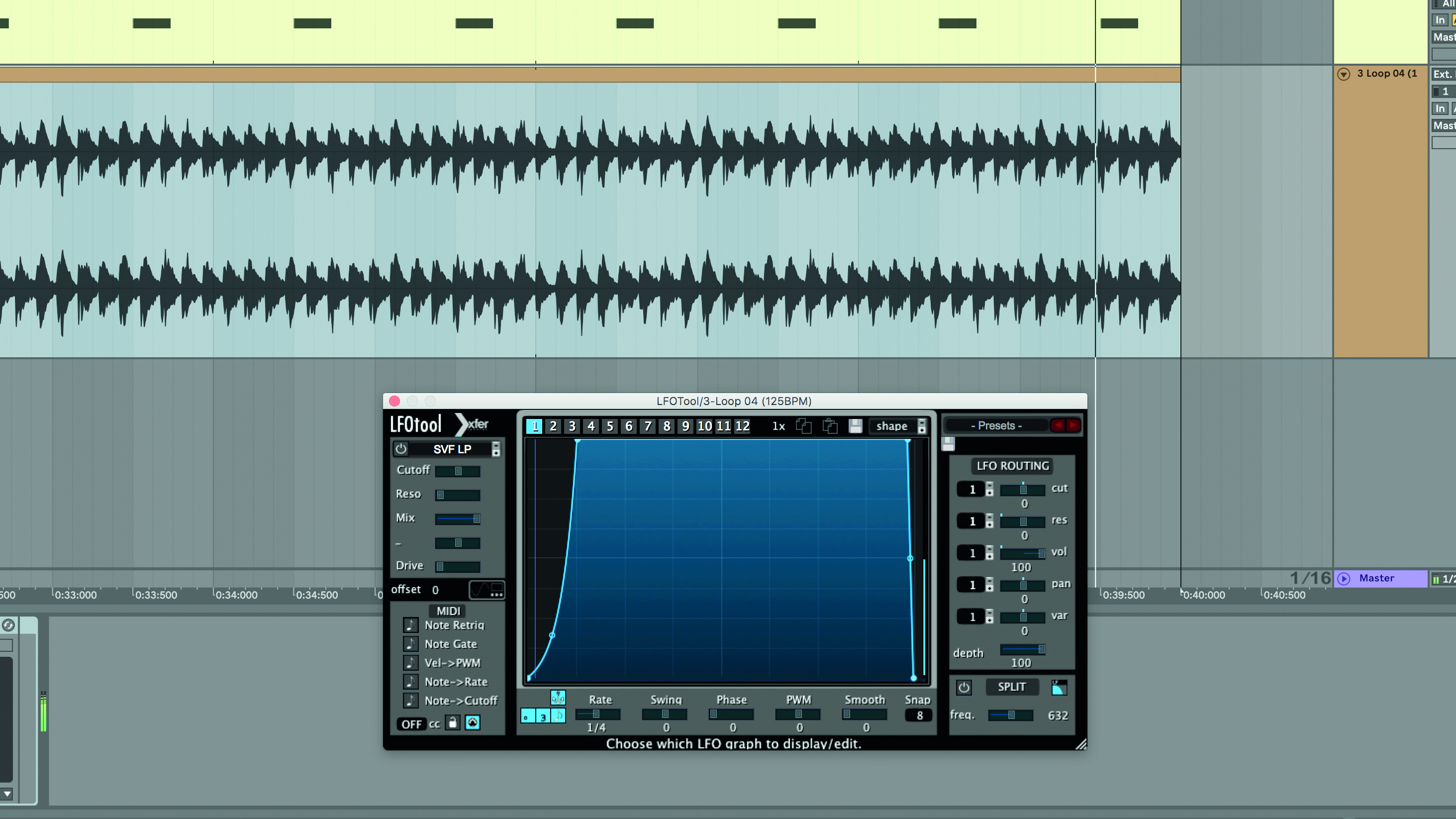

Though this basic principle is easy to grasp, the nuance of drum synthesis lies in the response of that envelope shape, and a bog-standard, virtual analogue-style ADSR envelope probably won’t provide the level of control you need over the pitch fall’s curve or profile.

Thankfully, plenty of modern synths now offer more malleable envelopes designed for the task - the likes of Xfer Records Serum and Native Instruments’ Massive X. The former comes with an array of identical breakpoint LFOs that can be flipped to one-shot envelope mode, allowing you to draw, sculpt and bend the exact envelope curve required; the latter comes with a proprietary Exciter Envelope specifically designed for the creation of percussion and front-end ‘punch’ shapes.

These methods are used to replicate a drum’s pitched component – ie, the resonant tone that’s created when a drummer strikes a drum – but there’s also a ‘splash’ component, too, which can be emulated by filtering and enveloping noise. Most synthesisers feature at least one white noise oscillator, but many modern synths go even further and offer sample-based noise sounds recorded from various sources. By blending a pitched tonal body with noise in this way, you can recreate the majority of analogue-style synthetic drum sounds with relative ease.

If you’re looking for go-to tools for drum design, dedicated drum synths are also available – some designed to emulate classic analogue drum machines, some based on original designs, and others a hybrid of the two.

For building bass drums, for example, virtual instruments such as Sonic Academy’s Kick 2 or Plugin Boutique’s BigKick serve up a combination of sample-based ‘click’ layers with an ultra-precise, pitch-shapable synthetic layer. And then there are multi-part drum synth instruments such as Rob Papen Punch and Sonic Charge MicroTonic, which provide entire synthetic kits ready to be manipulated and customised. You can find a roundup of today’s best software drum machines here.

Transient considerations

Generally speaking, your kick drum and snare/clap supply the rhythmic one-two punch that defines your overall beat’s power and impact. This means that you need to pay close attention to their transients – ie, their initial front end – and how they cut through the mix in relation to the other sounds going on at that point in time.

Many different instruments feature front-heavy components that can occur at the same position as your drums on the timeline, which can blur and smear overall transient detail. The character and prominence of your kick, snare and clap’s transient is often dependent on the genre you’re producing, plus the other sounds going on in the mix. With that in mind, let’s look at a trio of considerations for transient success.

Many tracks feature a kick drum with a softer, less prominent transient. The benefit of this approach is that you can give your snare or clap a sharper front end, which will contrast nicely with the ‘flatter’ kick; and other sharp sounds (eg, synth riffs) can poke through over kick notes.

Other genres demand a bass drum with a bright, defined transient click. In this case, you want the kick to consistently cut through the mix, which you can facilitate by pushing other mix sounds out of the way every time the kick occurs using sidechain compression or volume shaping.

If you need to improve the definition of your kick and snare/clap transients, you may need to tame the dynamics of other sounds occurring at the same time. Try grouping all other percussion to a single bus before applying overall clipping or limiting – this’ll shave off undesirable spikes and help the core hits smack through.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.