The electronic music producer's guide to vinyl

Mixing and mastering issues considered

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Vinyl has made a mainstream comeback in recent years, but in the dance music realm it never really went away. Whether as a format for releasing your tracks, a part of your DJ setup, or a ready source of sample material, there’s a good chance vinyl records will play a role somewhere in your music making. Whether you’re a vinyl purist or not, it’s worth understanding the appeal, peculiarities and specifics of vinyl records.

In the near 40 years since the introduction of the compact disc, the popularity of vinyl has fluctuated somewhat but steadfastly refused to die away. Theoretically superseded by the convenience and reliability of CDs – themselves now rendered outdated by MP3 players and streaming devices - vinyl, by rights, should be a thing of the past; obsolete technology looked on with affection by those who grew up with it, but with little to offer the music consumers of today.

Despite this, though, in 2020 vinyl records made up a not-insignificant portion of all music sales. In fact, in the second half of 2020, vinyl records outsold CDs in the US for the first time since the 1980s.

In the UK meanwhile, vinyl sales were up 4.1% year-on-year in 2019 according to a report by the British Phonographic Industry, with 4.3 million LPs sold during that year.

So what is it about vinyl that gives it this longevity? Many vinyl fans will tell you it’s to do with the sound. While it’s objectively true that music on vinyl can sound different to other formats - as we’ll get onto, the production and mastering process plays a significant role - you could get endlessly bogged down in reading the numerous articles, blog and forum posts online about the sonic qualities and merits of different formats.

Whatever factor the sound itself plays in vinyl’s popularity, it’s probably fair to say the physicality of it plays a role too. In an age where our main engagement with music often comes through streaming tracks we don’t actually own, vinyl’s size and feel, and the design possibilities that come from record sleeves, labels and colour or patterned records, add an undeniable appeal that sits in stark contrast to the disposability of a Spotify shuffle or YouTube playlist. There’s something somewhat ritualistic about placing a vinyl record onto a turntable and watching the needle slide across the grooves; it is, very literally, bringing music back into the physical realm.

Vinyl’s resurgence has spread beyond niche genres into the realms of casual shoppers buying classic LPs at their local supermarket, but even before its mainstream resurgence the links between vinyl and dance music have been stronger than that of most genres. Prior to the rise of CDJs in the mid-’90s, vinyl turntables were the main format used by club DJs, and even as digital DJ gear has grown in popularity, vinyl has remained a key format for DJs and dance music fans.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Vinyl’s influence on the art of DJing is so engrained that even young DJs who might have never touched a turntable in their lives will likely find themselves using techniques and terms derived from vinyl mixing. The very concept of a ‘deck’ in a DJ setup is vinyl parlance, and techniques such as scratching, juggling and beatmatching all have their origins in the physicality of vinyl mixing.

As an electronic musician, there are potentially three ways vinyl could fit into your music making: as a format for you to release your own work on, as a format to DJ with, or as a source of sample material. However you’re likely to interact with vinyl, it’s worth taking a quick recap of what goes into making a vinyl record.

Pressing issues

The process of creating and mass producing a vinyl record begins by creating what is known as a master lacquer. This is a lacquer-coated aluminium disc that is precision etched by playing the audio through a lathe, which mechanically translates the recording into a physical groove.

Master lacquers are created for each side of a vinyl record, which are then sent on to a manufacturing plant where they’re used as the basis to generate metal stampers. It’s these stampers that are then used to press the mass-produced records.

As with most released music, tracks will need to be mastered before the lacquer can be created, but the considerations and techniques used are likely to be slightly different to mastering a track for, say, streaming or radio play.

Cutting tracks to vinyl is not, however, a one-size-fits-all affair. Creating a vinyl record is, in fact, something of a constant balancing act, where considerations of space, volume and quality are often in competition. For instance, it’s worth remembering that the circular distance around a record is considerably more at its outer edges than it is towards the centre of the record. This affects not only the amount of music that can be fit onto a record, but also the quality; broadly speaking, the outer edges of a record produce better audio quality than the inner section, where high frequencies tend to be duller.

In vinyl’s heyday, albums were sometimes sequenced specifically to work around this, whereby more sedate tracks would be placed toward the centre of each side of a record. In the case of dance music 12-inches, which tend to be limited to a single track or a few minutes of music per side, you’ll usually see that the music lives toward the record’s outer edge, often with a good chunk of free space in the centre.

There’s also a direct link between the amount of music fit onto each side of a record and the playback volume. Put simply, the more music you try to fit onto a single side of vinyl, the smaller the groove needs to be, resulting in a quieter record. These are all factors an experienced, vinyl-focused mastering engineer will be able to offer guidance on. As an artist, even if you plan on paying somebody experienced to help master and create records for you, it’s worth knowing how these considerations will affect the final release.

"vinyl’s resurgence has spread into the realms of casual shoppers"

Dubplate madness

One anomaly to the usual vinyl manufacturing process is the idea of cutting and playing dubplates - a technique born out of Jamaican soundsystem culture but common in a lot of dance music too, particularly jungle, dubstep and DnB. Dubplates are essentially test records, traditionally cut to 10-inch acetate using a master lathe. While these were originally merely a step on the road to mass-producing a record, they were widely adopted by soundsystem DJs as a way to play exclusive and brand new music that rival systems wouldn’t have access to.

The tradition naturally trickled down to dance music, too. Before the advent of digital files or CD burners, dubplates were essentially the main way for DJs to play out unreleased music.

While technology has made them less of a necessity, there are still plenty of vinyl-centric DJs keeping the tradition alive. These days, only certain specialist studios tend to offer dubplate cutting as a service. Fortunately, technology has also made the process slightly easier and more reliable, and modern dubplates are often cut into plastic and last longer than classic acetates, which were known to wear out quickly.

Vinyl masters

Mixing and mastering a track for vinyl release can involve additional considerations and mastering decisions. Let’s examine the basics...

As has been covered in these pages plenty of times, mastering is a process requiring no shortage of skill and numerous specialised processes, and that is particularly true of mastering for vinyl.

Creating a master for vinyl is inherently different to creating one for streaming, CD or digital release, as the physical process of turning a track into a groove, and then playing that groove back via a turntable, puts a number of constraints on a track in terms of dynamics, frequency range and stereo field.

Generally speaking, the best advice for electronic producers preparing their work for vinyl release for the first time is to seek out the help of a mastering engineer who knows their stuff. Even when doing this, however, it can be useful to understand a few core concerns…

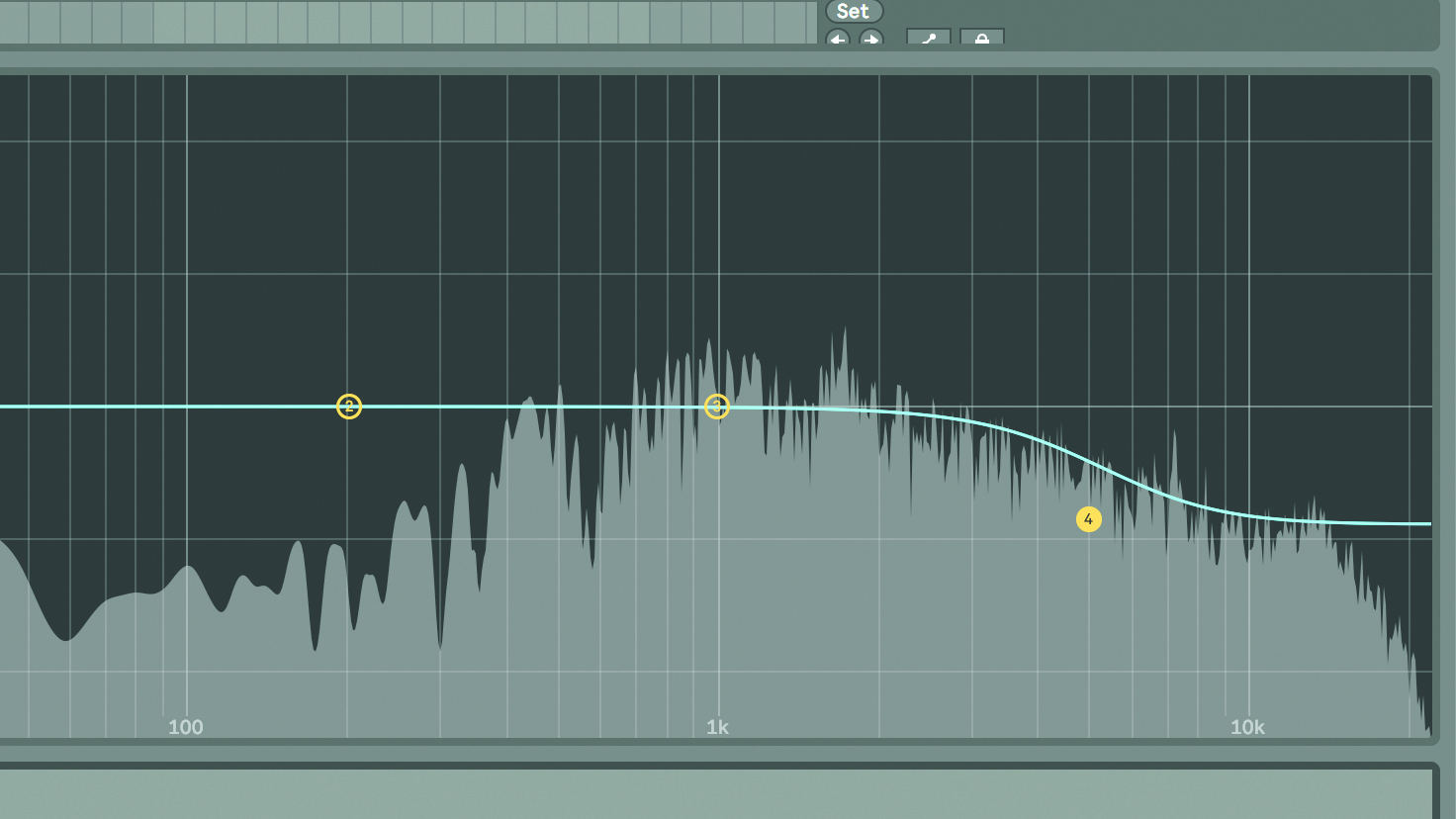

Step 1: A track with too much high frequency content or lots of sharp transients can cause a record to distort on playback, and even at the best of times these frequencies are often lost during the process. Rolling off upper frequencies can help maintain overall clarity.

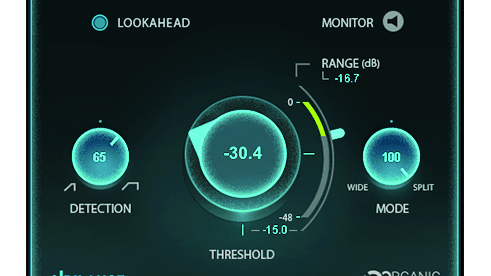

Step 2: Sibilance can cause real problems with vinyl playback and tracks may need to be run through a de-esser. If your track features a vocal, it’s a wise move to make sure you’re de-essing at the mixdown stage to make your mastering engineer’s life easier.

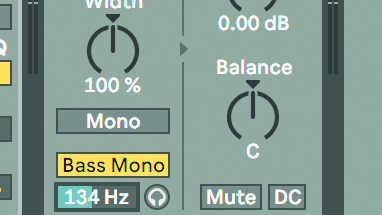

Step 3: Bass frequencies can cause problems in two main ways - through too much stereo width, or as a result of phase issues. Bass frequencies should be put into mono for cutting to vinyl, and you should check mono compatibility at the mix stage.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.