Learn the basics of Indian music for guitar

Redefine your playing with a foundation in raga

Indian classical music is rich with ideas which will broaden your guitar playing. This lesson requires no prior knowledge, and will cover some core concepts from North India’s Hindustani tradition.

Don’t be put off by Indian music’s reputation for complexity - the basics of rāga and tāla are surprisingly straightforward. Let’s start by listening to Raag Bageshri’s fiery climax - turn it up!

North India has been a musical melting pot for millennia. Folk melodies and Vedic temple chants were intertwining over 3,000 years ago, and the resulting music has been coloured by many other cultures - medieval traders, Indian Ocean settlers, the Mughal Empire, and colonial Britain.

Jazz and Indian music have crossed paths for almost a century now too, profoundly influencing guitar pioneers such as John McLaughlin, Jeff Beck, and Pat Martino, as well as shaping the output of John Coltrane, Miles Davis, The Beatles, and countless others. Indian Classical music captivated Jimi Hendrix, and will enthrall anyone with open ears.

So - what are the basics of Hindustani music? I think these are the most important first concepts for Western instrumentalists:

Rāga - a melodic ‘recipe’ to guide improvisation towards particular moods.

It’s an aesthetic concept as much as a technical one - rāga can be translated as ‘that which colours the mind’.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

They’re more than just scales - each rāga is based on a defined set of notes, but with other instructions too - for example chalan (characteristic phrases), vadi & samvadi (‘king’ & ‘queen’ notes), and sruti (microtones). We’ll start to look at these ideas in the examples below.

Tāla - rhythm cycle (‘clap’).

Typically played on tabla (hand drums), which improvise and guide the soloist around intricate grooves. A rāga performance usually progresses through several tālas, speeding up to a final climax.

Common classical tālas include tintal (16 beats), ektal (12 beats), jhaptal (10 beats), and rupak (7 beats). Indian music, like funk, often resolves hard onto the first beat of a cycle (‘get it together on the one’).

Alankar - ornamentation and ‘musical decoration’.

There are elaborate ways of squeezing more out of each note, and melodies are rarely played ‘straight’

Hindustani music has a distinctive feel, with unique bends, slides, and vibratos. Soloists seek to mimic and extend the expressive flexibility of the human voice (gayaki ang).

There are elaborate ways of squeezing more out of each note, and melodies are rarely played ‘straight’. Indian violinists slide around the fretboard, sitars allow for singing vibrato and sweeping bends, and lap slide guitars have recently been adopted. Lesson 2 will cover alankar in more depth.

Before we start breaking the music down, we should listen to it more closely. After all, Hindustani is typically learned by ear, with minimal conversation or writing. Some of my teachers spoke no English aside from basic instructions like ‘finger running’ (meaning ‘go faster’). Actively teaching yourself is the most powerful way to learn.

Listening to the core ideas

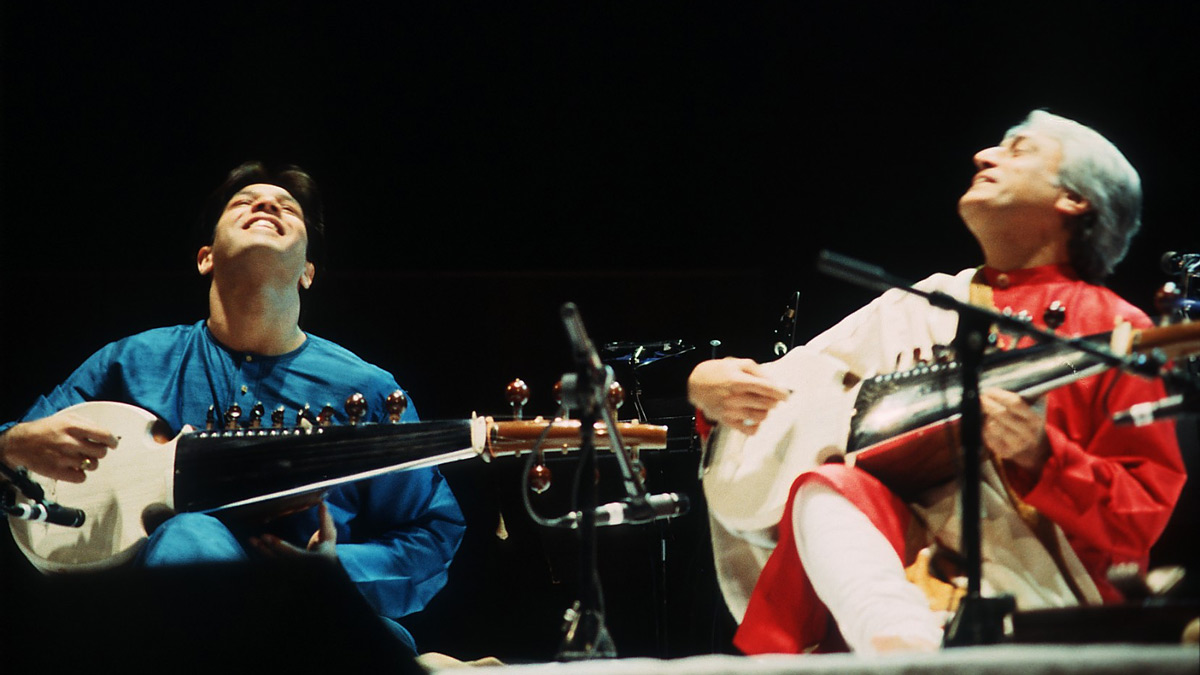

We’ve been listening to the fast final section of Raag Bageshri, by Shahid Parvez and Kumar Bose (sitar & tabla). Now we’ll pick it apart a bit. Don’t worry about not knowing much yet - theoretical study is usually just giving a structure to what we can already hear. For now, just open your ears.

Listen out for the key elements. What mood does the rāga conjure up? Which tones can you pick out? Can you tap your fingers along to the tāla? How do alankar give more life to the notes? What else is new or surprising?

Here’s how I think the three key concepts above (rāga, tāla, and alankar) are at work. We’ll put them in a guitar context after listening - be patient (yeah, I know, it’s hard...).

Rāga (melodic mood recipe)

Bageshri aims to evoke pratiksha (‘awaiting’), the tension and profound longing of waiting for a lover to return. It roughly corresponds to the Western Dorian mode, but with more detail - for example the 5th is often omitted or played weakly. Hear how the 5th is largely absent from the ascending lines at 2:07-2:26, decluttering the sound.

This rāga often emphasises the 2nd scale tone, and Shahid Parvez ends his first melody phrase on it (0:00-0:10). This gives a ‘sincere’ minor 9th chord feel, with tension between the 2 and adjacent b3. The 1 and 4 are the vadi and samvadi (king and queen notes), played strongly throughout. Try picking some of these tones out - if your ear gets lost then go back to the main resonating tabla stroke, which is always tuned to the root.

Tāla (rhythm cycle)

Kumar Bose plays a 16-beat tintal cycle on the tabla, counted fast at 280bpm upwards. The cycle stays steady for a while, then breaks down into syncopated passages (e.g. 5:22-5:40). It’s an intricately funky groove - try tapping your finger in an even stream of notes and pick out the emphasis where you can.

Also listen to how tintal’s third bar (roughly speaking) is often absent of resonating tabla strokes (e.g. 1:20-1:38). This space is emphasised by the lack of a melodic bass instrument - the low-pitched tabla strokes speak and sing, adding groove to the ‘bass space’.

Alankar (ornamentation)

The rāga heavily ornaments the 2nd and 6th scale degrees. Shahid Parvez uses vibrato to draw you into the melody (0:30-0:40), and often bends upwards to the very highest notes, giving them a ‘quivering’ feel (0:58-1:11).

He adds further momentum with slides (1:31-1:43), and turns quick note flurries (2:07-2:26) into fierce unbroken scale patterns (2:26-2:55), before settling back into ornamenting the main groove (2:55-3:13). We’ll stop there for now.

The tanpura drone is also important. Here it’s tuned to the ‘king and queen’ notes (1st and 4th of the scale), providing a consistent background that keeps solo phrases firmly anchored. It allows the sitar to create sustained tension without the listener losing the feel in long passages (the never-ending lick at 4:52 has left shredder friends of mine speechless).

How might you start applying this to the guitar?

All examples (fast & slow)

Example 1 - Raag Bageshri

We’ll start by playing some of Raag Bageshri, in the key of E. Put on this tanpura sample, comprised of E and A (1st and 4th). In this key we can also mimic the tanpura by brushing across open E and A strings. Note Bageshri’s ‘weak 5th’ - the 4-6 jump leaves a wide space, opening and brightening the sound. Have a go - first the scale, then an example melody with some suggested bends and dynamics:

The melody demonstrates some of Bageshri‘s core concepts - try using it as a ‘base’, and improvise to and from it using these ideas. Hear how the tanpura grounds the sound. Can you evoke pratiksha?

- Dorian mode with strong 1, 2, 4, 6, weak or absent 5

- Emphatic use of 1 and 4, spacious ‘4-6 jump’

- Alankar bends and vibrato on 2 and 6

Example 2 - Raag Jog

Now let’s listen to a new rāga - Raag Jog, from a classic duet recording by Ravi Shankar & Chatur Lal. Jog means ‘state of enchantment’, and the scale used to conjure it is similar to our minor pentatonic. But again it has more detail, mixing major and minor 3rds for a finely balanced and almost bluesy tension.

In aroha (ascending form) it takes a major 3rd, to form 1-3-4-5-b7-8. In avaroh (descending form) it has both a major and minor 3rd, going down as 8-b7-5-4-3-4-b3-1. Note the characteristic ‘3-4-b3 zigzag’. The zigzag is a key part of Jog’s chalan (characteristic phrasings), keeping the mood elevated and combative. It favours strong phrasings, often starting from 1st and 3rds.

Line one below notates Jog’s rough structure, and line two uses it in a melody. We’ve chosen they key of A this time, so use this tanpura sample. We can again mimic the tanpura by brushing the open E and A strings, but this time open A is our root (E is the 5). Emphasise the final b3 of the zigzag with a small upward bend:

The study showcases some distinctive features of Jog. Base improvisations around the riff using these ideas:

- Major 3rd on the way up, both 3rds on the way down

- Strong phrasings, root and 3rds as common starting tones

- ‘3-4-b3’ zigzag resolution

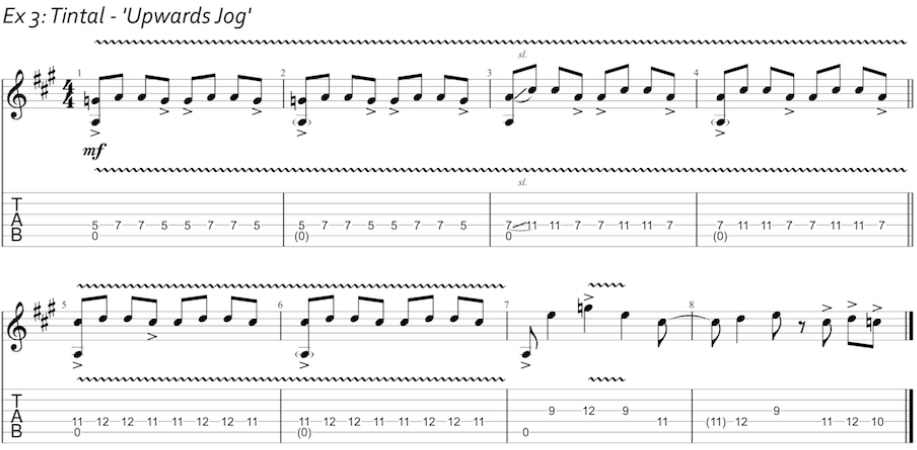

Example 3 - Tintal Rhythm Study

For the final study we stay in Raag Jog. It will help you feel the tintal cycle, very popular in Hindustani music. Patterns like this are a great way of building and releasing tension in a loop: rising up the scale gradually using adjacent notes and repetitions, then descending suddenly.

Use it to sharpen your right-hand dynamic control, and really drive the rhythmic flow. Build volume as the pattern rises, and release tension hard in the resolution lick (emphasise Jog’s characteristic ‘3-4-b3 zigzag’ on the way down). Try improvising your own final bars - use your imagination!

It goes without saying that we’ve barely scratched the surface of how Hindustani music can enrich your playing. And we’re only approximating the rāgas here - fully embodying them takes a lifetime. More of these lessons are on the way - we’ll learn about concepts such as tāla (Hindustani rhythm theory), alap (rhythmless introduction playing), and taans (long-structured fast phrases).

The three examples above are just a starting point - it’s more about the ideas than the specific forms they take here. As ever, the best way to learn to actively listen - keep your ears open, sing/tap/play along, and improvise from there on the instrument. Enjoy learning about non-Western music!

Suggested listening:

- An Introduction to Indian Music - Ravi Shankar: Hindustani music’s late global superstar explains and demonstrates the basics of rāga [4 mins]

- Raag Jog - Rakesh Chaurasia: solo bansuri flute version of our second study rāga, with fiery rhythmic loops from about halfway [5 mins]

- Raag Bageshri - Shahid Parvez & Anindo Chatterjee: enthralling live version of our first study rāga, showcasing some playfully intense sitar & tabla interplay [final 15 mins]