How to optimise your bass frequencies for the club

Get your basslines and kick drums working from the same page with our tutorial

The biggest factor to consider when creating and mixing club music is bass. There’ll obviously be a huge difference between how bass frequencies sound in your studio (or headphones) and how they come across when blasted through an enormous PA system. Ever heard a record that features a restrained, almost ‘weedy’ low end at home, but suddenly turned into something altogether more weighty and monstrous in the club? Of course you have.

First, your low end must be tight. The overlapping of bass quickly causes sub flap, mud and blur. Your kick drum and bass must be separated, and their fundamental frequencies should live as far apart as is humanly possible.

If low bass sounds do share frequency content, as they appear to in many genres, then you must make sure they never really occur at the same point in time. This temporal placement is a big reason why heavy kick-to-bass sidechain compression became so widespread and trendy a few years ago: that cliched trick allows for both a weighty bass drum and heavy bassline to coexist in tandem. That trend has subsided somewhat, thankfully, but more covert sidechain compression or volume ducking can still pocket space for a kick to punch through.

Genres such as house place more low-frequency emphasis on the kick, with the accompanying bassline riding above in the ‘upper bass’ frequency range. Conversely, ‘bassline’ styles such as drum ’n’ bass and dubstep feature knockier, punchier kick drums that allow the bassline to take the more prominent low-end role. This kind of juggling act is the best way to let those bass elements live together.

As a general rule, the best approach is to simply choose the correct kick drum sound to complement the right bass sound. A punchy kick is quite obviously going to clash with a knocky, kick-like bass sample, but the same kick sound will probably sit nicely over a smoother, sustained sub bass synth.

Frustratingly, many modern pop, hip-hop, trap and electronic productions seem to pack in mega-phat kick drums and sub bass. This is more difficult to dial in, but can still be done - you just have to choose your battles. One important factor is the duration of bass over time. Many kick samples feature long, subby tails, which obviously clash with sub bass; so by shortening the kick, you’ll reduce its temporal impact, making it easier to gently, invisibly duck the sub bass for that duration, or pack in volume-faded bass notes where needed.

To boost your kick’s perceived impact while actually reducing its physical footprint in the mix, use saturation and transient shaping to make it punch harder, then carve away its extreme sub with EQ to shift listener perception. And if you need to keep the kick’s meat after all, try displacing the bassline until later on, so notes occur just after the kick, but not so much as to disrupt the groove.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

In the following walkthrough, we'll show you how to strike the right balance of bass power and clarity. And there's more advice on the subject to be found in the full Mixing For The Club feature in the October 2018 edition of Future Music.

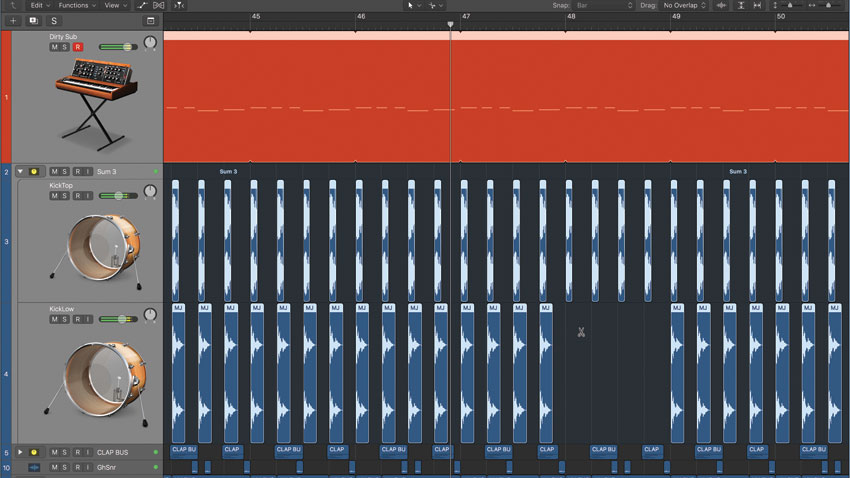

Step 1: Ultimately, you need to make sure your club mixdown contains enough sub juice for big PAs and subwoofers without creating a mushy mess of overlapping low frequencies. Define either the kick drum or bass as the dominant sub-driving element, then gear your production around making them fit.

Step 2: Once you’ve volume-levelled the kick and bass, it’s time to evaluate the frequency balance in context. If, for example, you’ve been finding that the bass is occupying most of the low end, you can probably cut some of that low area from the kick - or vice versa, if that’s what’s required.

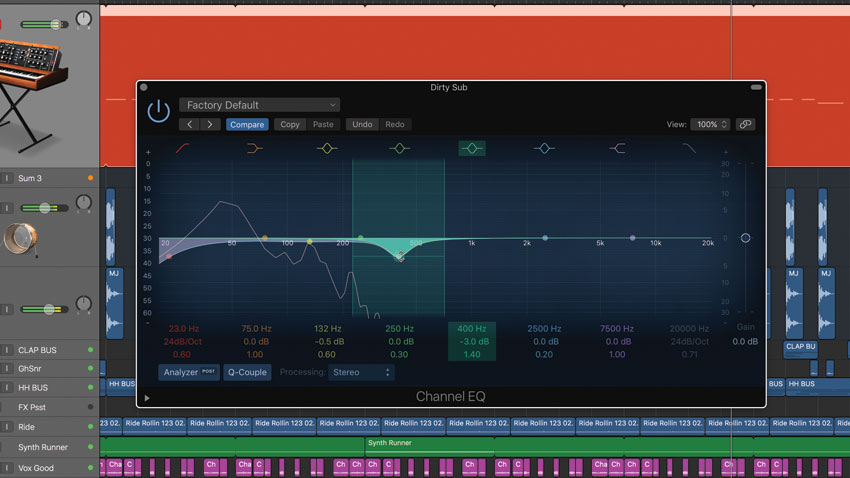

Step 3: If both the kick and bass have enough time to do their thing in the low end, use some sidechain-driven filtering or EQ to pocket space. Make the kick as short as it can be without sacrificing perceived ‘size’, then ‘push and pull’ the sub’s frequencies to pack sub into the kick’s gaps.

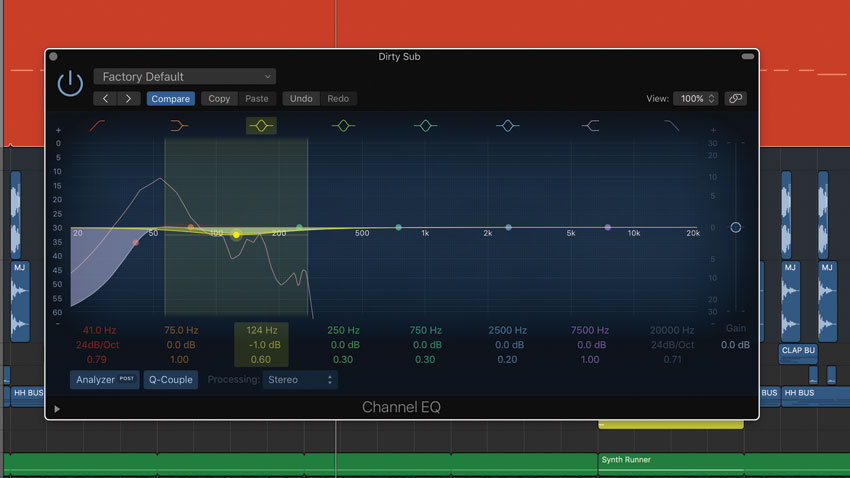

Step 4: Low-mid and midrange mud will cloud the mix, and obstruct bass power. If your bassline’s weight feels compromised, try dipping muddy 300-500Hz harmonics with EQ - but don’t eat into the harmonic ‘meat’ too much. The same thing applies to kicks that sound a bit on the ‘bloated’ side.

Step 5: Your synth bass will probably come to comprise different frequency ranges: sub heft, lower-mid thickness and upper-mid ‘bite’. Consider keeping the upper and lower mids a little more ‘dynamic’, and flatten the sub frequencies a bit more for consistent power on big rigs.

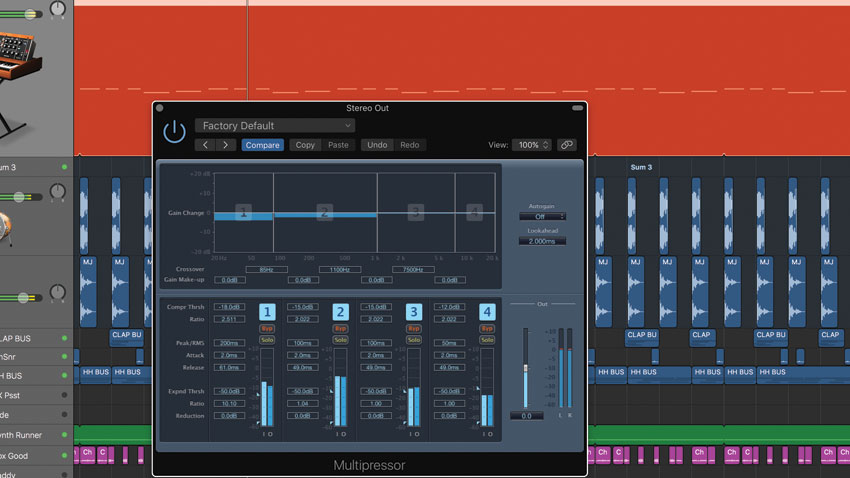

Step 6: If your track features multiple bass elements - eg, call-and-answer synth one-shots and ‘growls’ - then group them all together. That way, you can even out sub bass uniformly by applying a single stage of multiband compression, then pulling down the sub-80Hz frequencies by a small amount.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.