How to get your music featured in video games

Tips from the pros at Activision Blizzard

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

After three decades of creating gaming products, Activision Blizzard Inc. is a cornerstone in the video game world. The company’s Director of Music Affairs, Brandon Young, has been responsible for the music aspect of those games for the past decade.

Young is involved with every facet of the music, from working with the development studios on the titles to finding composers for scores to executive producing those scores to licensing songs and brokering deals, to partnerships with artists and musicians, and coordinating with marketing teams and advertising agencies for promotional trailers. With titles like Call of Duty, World of Warcraft, Guitar Hero, and DJ Hero, among many others on his résumé, Young has dealt with a wide range of musical duties. Here, Young shares some insights for composers looking to break into the game world.

Which do you tend to do more: license music or hire composers?

"It’s definitely game-by-game. We did 13 to 15 game titles for 2013. Seventy per cent used hired composers and 30 per cent were plugged in from different music houses and licensed music. For some of the smaller titles, like Cabela’s Hunting Game, the music gets pulled from different library-type music houses like Killer Tracks. We had years of doing titles like Guitar Hero; obviously heavily licensed music. My preference would be to hire a composer every time, but it depends on what we’re trying to do."

What is your process for choosing a composer?

"It starts internally. I talk with our studio about what that game’s going to want and need, and we look at the budget. From that, I pull a shortlist of seven people. I share their reels with our internal producers, as well as the studio, and we narrow it down to three. Then we check on their availability, see if they’re interested, see if the budget meets with what they’re into doing, and go from there."

How do you work with the composer to get the results you need for the game?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"For something like Call of Duty, our massive juggernaut title, I’m taking the composer to our studio in San Francisco to do a full two-day summit with the creative team, really immersing him with what our goal is. He’s going to see levels that have already been developed, but there are still plenty of levels to go. We’ll show him the script and the creative treatment for the game. We’ll take him through the vision decided by the developer."

What does a composer need to understand about scoring for a game versus other mediums?

"Video games are nonlinear. We have audio engineers who do the implementations. They have to set up the music as stems that can be layered. For instance, if it’s Call of Duty and your guy is standing in the corner and it’s quiet, you need that to be low. When the action starts happening, you have to program it so it starts bringing in the different layers of stems to create that action feel behind it, which isn’t done in any other medium. The composer has to understand that early on, before we get into our projects, that we’re a nonlinear product; how to write and adapt for that."

How do you find composers? Or track down new music?

"I try and keep of list of people I meet, whose friends represent, who are friends of friends of friends. I used to dig on my own, but that’s not necessary anymore. I’ve been doing this job for so long, I stay ahead of it with what people send me. I’ll discover something whether it’s through Sirius Radio or someone mentioning it, and I’ll search my inbox and 90 per cent of the time, it’s in there. I get inundated. There’s only so much I can, or want to download. If it’s a stream or download then at least you have the option."

Are there particular musical styles that you tend to gravitate toward for games?

"Stuff that has more energy, from harder, aggressive rock to hip-hop to something electronic and a little darker with power to push. Everyone’s into instrumentals these days, so music is being sent out as “full album” and “instrumental,” which is helpful."

Can someone approach you without a reference?

"They can. If they email me a 20Mb file that jams my inbox, it discredits them and I’m going to delete the attachment. If they are unable to construct a normal sentence, they come across unprofessional and I don’t know if they’re going to hit my deliveries on time. If they email me a link and present themselves by corresponding in a professional manner, I will check them out."

Do you tend to respond?

"I try to get back to people if I feel it’s a legitimate request. If I have projects going on that they can submit for, I’ll let them know. If I don’t have anything at the time, I’ll let them know. I let them know if I have something starting around a certain month and to check back with me then. Sometimes I’ll flag people who are checking on certain things to get back to them. I get a couple of hundred emails a day and can’t go through all of them."

Do you ever use people who don’t have a track record? What can they bring to you to show what they can do?

"Yes, I do. The best thing to do if they don’t have any experience at all is to put together a reel. Pull images off YouTube, do your own spec score to it. Especially if it’s things I want to be seeing, like a clip of Call of Duty: Mute it, do your own score to it, see how that comes across. If you’re trying to convey a few different styles, a minute and a half, two minutes each. If someone feels like they have the right skill set for certain projects, they should approach companies that are doing things [that match] their skill set. Research different publishers and see what their annual titles are, to clue you into what they’re doing the next year. There are unannounced things, but you can figure it out. You can find out who to reach out to by Googling who was involved in a particular game. It’s a small enough industry to figure out who the people are."

If a musician or a label has a back catalogue of material, what’s the best way to present that to you? And is there paperwork you’d like them to have prepared?

"When people send me a whole back catalogue, I’m not going to listen to it because I don’t know where to start unless you do a focus tracks list. If you do a top-line sampling of the favourites, people can take a listen and decide. Links to SoundCloud work great. You can skip through the songs easily and if they want, they can set it up to be downloadable.

"They have to be able to confirm that they own it. They wrote the song, and if there were co-writers for the song, that those people are on board or they can put me in touch with the right people to make sure all the pieces of the puzzle are there. I’ve got the paperwork I can put together, no problem."

What are some external entities you work with that provide you with music that artists can approach?

"Our advertising agency, as well as digital agencies that work with our digital department running things like our social media. We’re always doing videos that go up on there. These agencies have their own audio people. It ends up funnelling back through me, but we go through hundreds of promo trailers a year so I’m usually cool with it if they have it figured out before it gets to me and I just end up doing the deal."

What’s the range for compensation?

"From a composer perspective, if you’re going to score an entire game, you can think of that running the spectrum from real small-budget films to massive blockbuster film budgets. It depends on the size of our game, our expectations for it, the level of quality we’re expecting, whether or not we want a big composer name value to it. There are a lot of different levels. There’s a per-minute rate that’s an industry standard that can run anywhere from $500 up to several thousand dollars. We might need 60 to 90 minutes of score to work itself through the whole game. We usually work on a chunk of minutes at a time.

"For license, if it’s a game that’s a music-based or a rhythm-based game, like a Guitar Hero, then you’re going to pay a penny-rate royalty. If it’s a song license, it’s subjective. It depends on the size of the artist, what they think it’s worth, the scene in the game. I’ve paid anywhere from low four figures to high five figures."

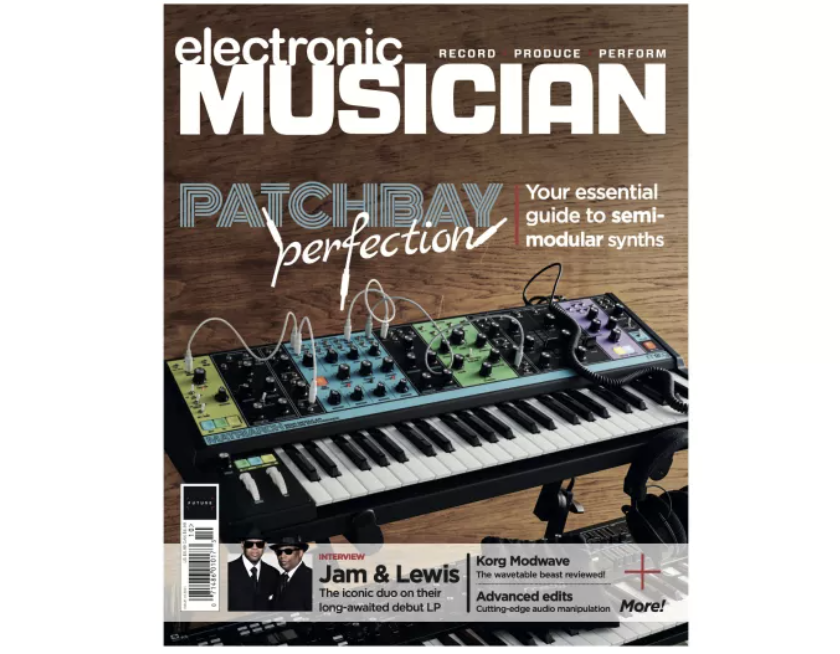

Electronic Musician magazine is the ultimate resource for musicians who want to make better music, in the studio or onstage. In each and every issue it surveys all aspects of music production - performance, recording, and technology, from studio to stage and offers product news and reviews on the latest equipment and services. Plus, get in-depth tips & techniques, gear reviews, and insights from today’s top artists!