How to create beats in different time signatures in your DAW

Break out of 4/4 with different time signatures in your DAW

The time signature of a piece of music is a pair of numbers written at the start of the stave when notated, or somewhere in or near the transport section of your DAW, that determine the number of beats in the bar (the first or top number) and the value of those beats (the bottom number). The rhythmic feel of a track that results from its time signature is called its ‘meter’.

4/4 – also know as common time – is very much the standard time signature in western music, and when the top number isn’t divisible by 2 – 3, 7, 9, etc – the time signature is generally referred to as ‘odd’.

Odd meters don’t crop up very often in most modern genres, but for some classic examples, you’d do well to check out Dave Brubeck’s seminal Take Five (in 5/4) and Blondie’s Heart of Glass (a bar of 3/4 replacing the otherwise persistent 4/4 in the section after the chorus). These days, they’re largely the preserve of progressive rock, where they’re used to brain-teasing effect, pushing the technical prowess of the drummer and other players to their limits.

Nonetheless, for the adventurous electronic producer, odd time signatures and meters present a unique creative opportunity, albeit one that can be tough to realise effectively due to the rigidly four-square nature of dance music. Here’s a crash course…

Step 1: Here’s our starting point groove: a straightforward 4/4 beat. So that’s four (the top number in the time signature) quarter-notes or crotchets (the bottom number) in the bar. This is the core of the vast majority of western pop, rock and dance music.

Step 2: Let’s begin our exploration of odd time signatures and meters with the most ubiquitous: 3/4. Setting the project’s time signature to 3/4 and removing the last beat from my 4/4 pattern transforms it to a waltz, with a snare hit in the middle of the bar. Alternatively, we can put the snare on beat 3 instead, or beats 2 and 3.

Step 3: 3/4 isn’t hugely useful in dance and electronic music, as it tends to sound quite archaic, but its double-time equivalent, 6/8 – six eighth-notes or quavers to the bar – certainly can be when you’re after a triplet-based, or – with beats 2 and 5 dropped from the hi-hats – shuffled rhythm.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Step 4: Let’s get freakier with 5/4. Adding a beat to our 4/4 original makes it sound very different, throwing the whole rhythm off beam and presenting a serious challenge in terms of danceability. This may be best saved for very occasional use as a twist at the end of a long 4/4 section, or for more ‘cerebral’ tracks.

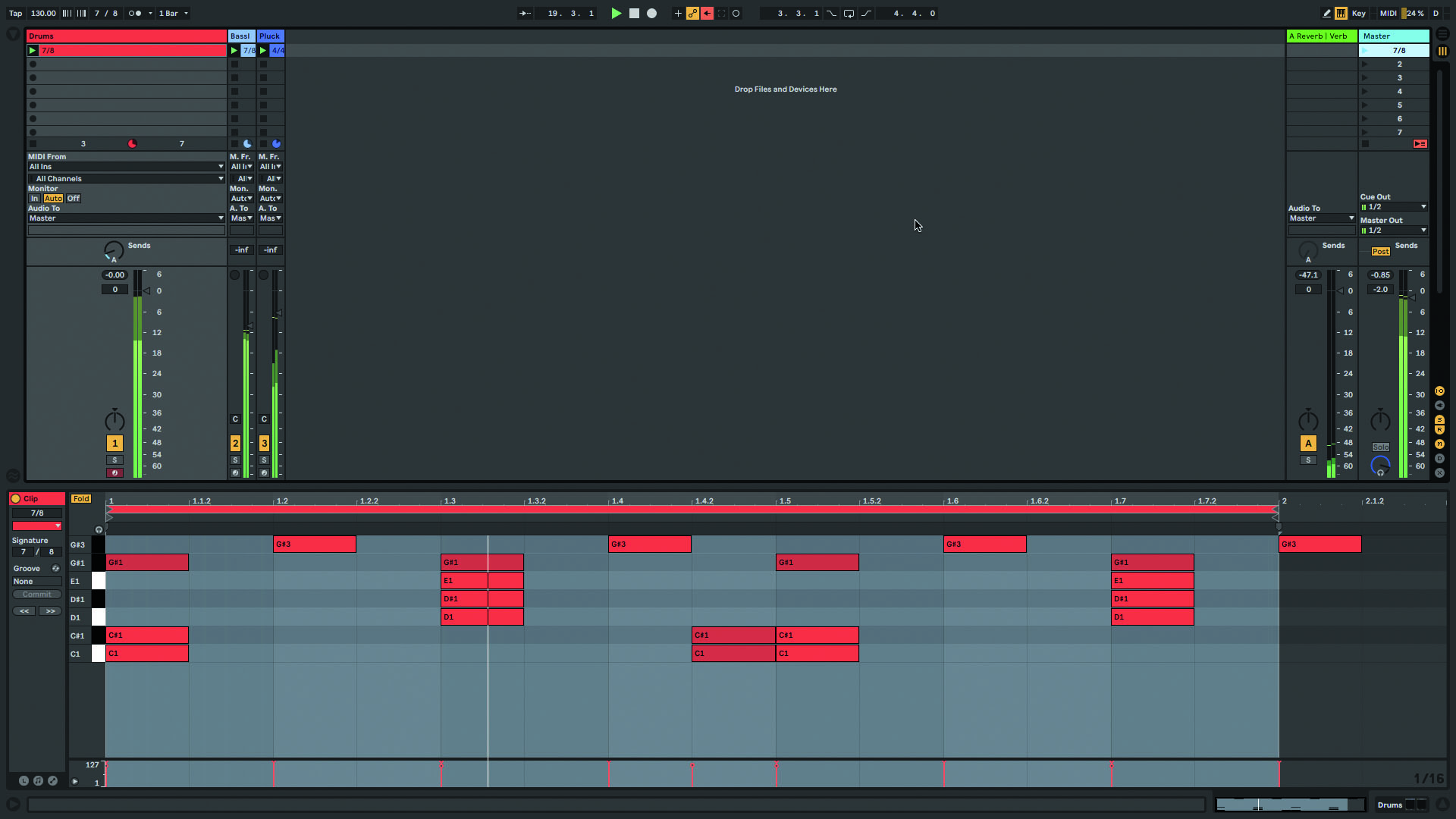

Step 5: How about 7/8, which takes half a beat off the standard 4/4 – ie, seven eighth-notes in the bar rather than eight? While 5/4 drags the bar out and comes across as lazy in its wonkiness, 7/8 feels more urgent and impatient, due to the downbeat (beat 1) coming around a little sooner than expected.

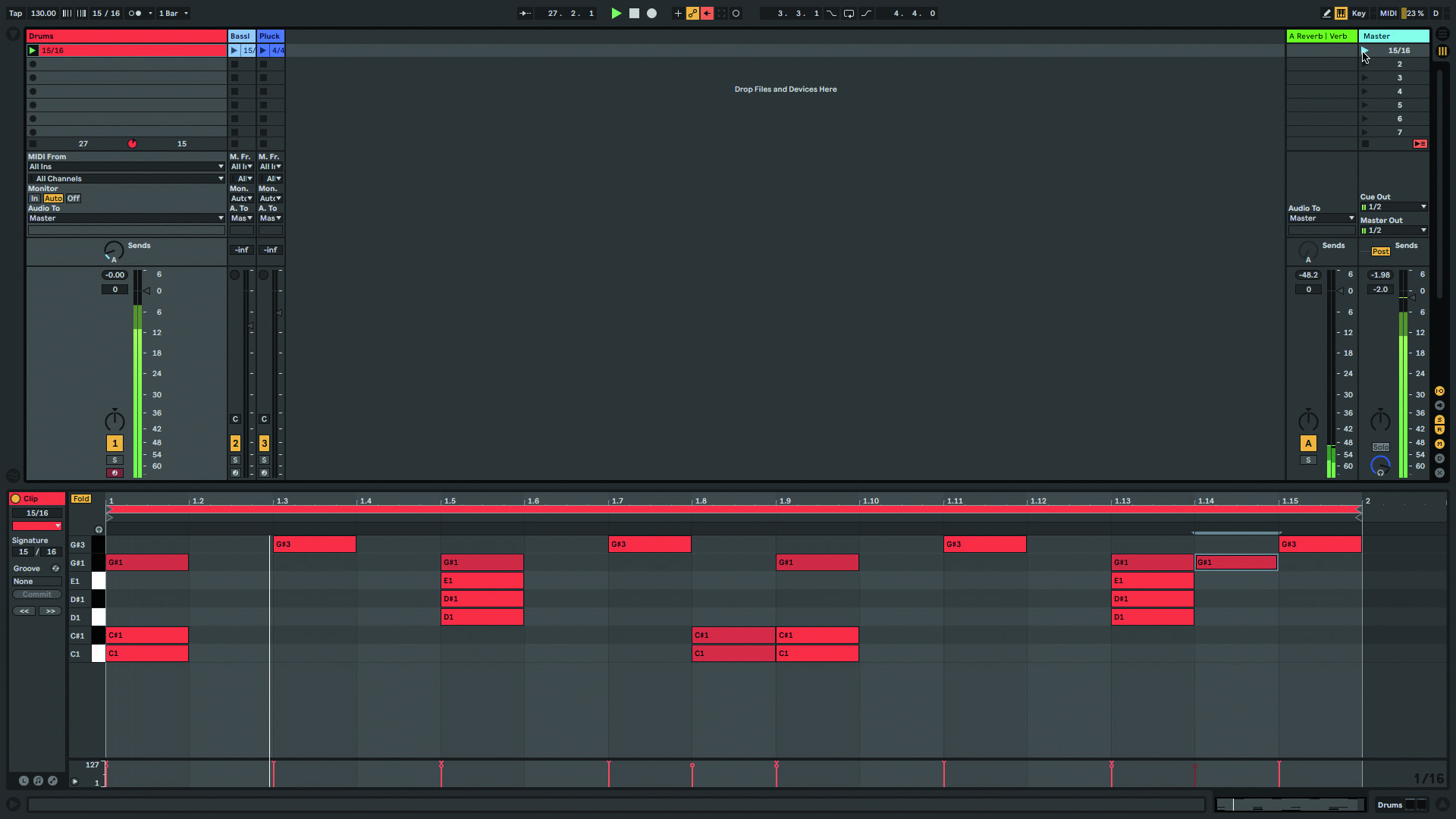

Step 6: Keep raising the time signature’s top number for longer bar lengths (try 9/4, 11/4 or even 13/4!), and doubling the bottom number beyond 8 for higher-‘resolution’ meter changes. Adding or dropping a 16th-note from 4/4 – aka 16/16 – for example, yields another style of temporal upset altogether.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.