"His piano playing and composition style has influenced both my development as a musician and, more significantly, music as a whole": A pro keyboardist gives you 5 ways to play like Bruce Hornsby

"Many years ago, I met Bruce as a wide-eyed 13 year-old," says Jeff Babko. "When his first record was released and exploded on the radio airwaves, I felt as if I’d brushed up against Superman"

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I once had the pleasure of seeing the Bruce Hornsby and Pat Metheny Campfire Tour at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles. I was immediately reminded of Bruce’s debut record The Way It Is, and the influence his piano playing and composition style had both on my development as a musician and, more significantly, music as a whole.

With its extended, Keith Jarrett-meets-Leon Russell-inspired piano solo, The Way It Is was quite a departure from the pop hits of the bands like Wang Chung, which permeated the airwaves of the day. It also went to Number One on the charts.

Many years ago, I met Bruce as a wide-eyed 13 year-old, inside the now-defunct Kingsound Studio in Van Nuys, California, where Bruce had cut the demos for The Way It Is. When his first record was released and exploded on the radio airwaves, I felt as if I’d brushed up against Superman. In the 1980s and ’90s, a time that celebrated programmed music, an inspiring figure that actually played music on an acoustic instrument was a rare treat. He continues to break boundaries even today, sneaking influences of contemporary classical composers like Arnold Schoenberg and Elliott Carter into his music.

One thing that’s particularly endearing about Bruce Hornby’s signature pianistic and compositional approach is that it somehow perfectly encompasses the sound of Americana music, saluting American composers like Charles Ives and Aaron Copland, as well as folk and bluegrass music, and the use of simple blues inflections and intervals such as open tenths.

Let’s explore some of Bruce’s signature musical traits. For continued study, I encourage you to dig deeper into Bruce’s vast recorded catalogue.

1. Great wide open intervals

Ex. 1 illustrates how Bruce often uses open intervals, with occasional jazz “crunches” like the minor eleventh in beat 1 of bar 2, and the minor ninth in beat 2 of bar 3. Also important here is the simplicity of the melodic content. If you just solo the top line as a melody, it is singable and almost hymn-like. This makes sophisticated or Copland-esque harmonies even more supportive and palatable for the average listener. Note that Bruce often favours the richness of “black note” keys like Gb and Db, which adds to the character and weight of passages like this one.

2. Go fourth

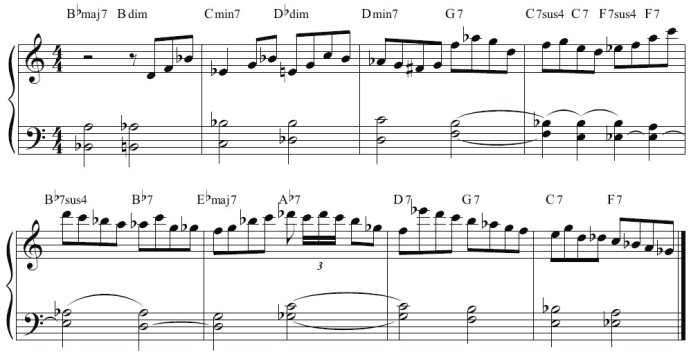

Ex. 2 explores Bruce’s use of quartal harmony, which is voicing in intervals in fourths instead of the more traditional discipline of building chords in thirds - as is most often associated with the seminal jazz pianist McCoy Tyner. An interesting aspect of how Hornsby adapts his quartal harmonies can be seen in this example, as it is juxtaposed over a simple boogie-woogie-type left-hand riff. (Check out Hornsby tunes like The Valley Road, Long Tall Cool One, Fire On The Cross, and the outro of Harbor Lights for more examples).

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

3. Your Own Walk

Hornsby’s songwriting style rarely includes garden-variety walk-ups and downs like I, ii min, I/III, IV, and the like. He likes to change things up as in Ex. 3,much like a jazz musician might reharmonize a tune, while always keeping in the Americana theme of open diatonic voicings with the bass note often providing the surprise element. In this short passage, what could be a simple walk up and down in the key of C gets a surprise when the bass hops up to the I-over-IV chord in beat 4 of bar 1. Also notice the 'crunch notes' here, like the minor eleventh in beat 3 of bar 1, and the minor ninth in bar 2 (grab both the B and C with your thumb). You can also grab the G and A in the final open F add2 chord with your thumb. (Check out the pre-chorus to A Night on the Town for another example of this technique).

4. Clusters

Hornsby often toys with famed jazz pianist Bill Evans-type chord clusters, as seen in Ex. 4. He usually shies away from basic triads, and when exploring the 'prettier' piano stuff, he often also shies away from dominant sevenths as well. These 'pretty clusters' combined with open fifths echo the Copland-like feel of Americana music. (Listen to the intro of The Show Goes On for an example.)

5. Open Fifths

Open fifths in the right hand, seen here in Ex. 5, impart a folky and anthemnic feel to Hornsby’s music. Note the cadence here as well; Hornsby rarely plays a typical rock V-IV-I or any variation thereof. He either changes the bass note to invigorate the inversion, or he changes the chord completely.

He also rarely resolves things to a major triad. In this case, he resolves to a powerful open fifth, from the IV chord with the third in the bass. (Listen to the intro to The River Runs Low, and the intro to Look Out Any Window to hear this kind of open fifth resolution).

Jeff Babko is best known for his spot in the house band on Jimmy Kimmel Live. He has recorded with Frank Ocean, Jason Mraz, Sheryl Crow and Alanis Morrisette, and served as a session keyboardist as movies such as Encanto (We Don't Talk About Bruno), Toy Story 4 and Killers of the Flower Moon. He's also the musical director and touring pianist for Steve Martin and Martin Short.