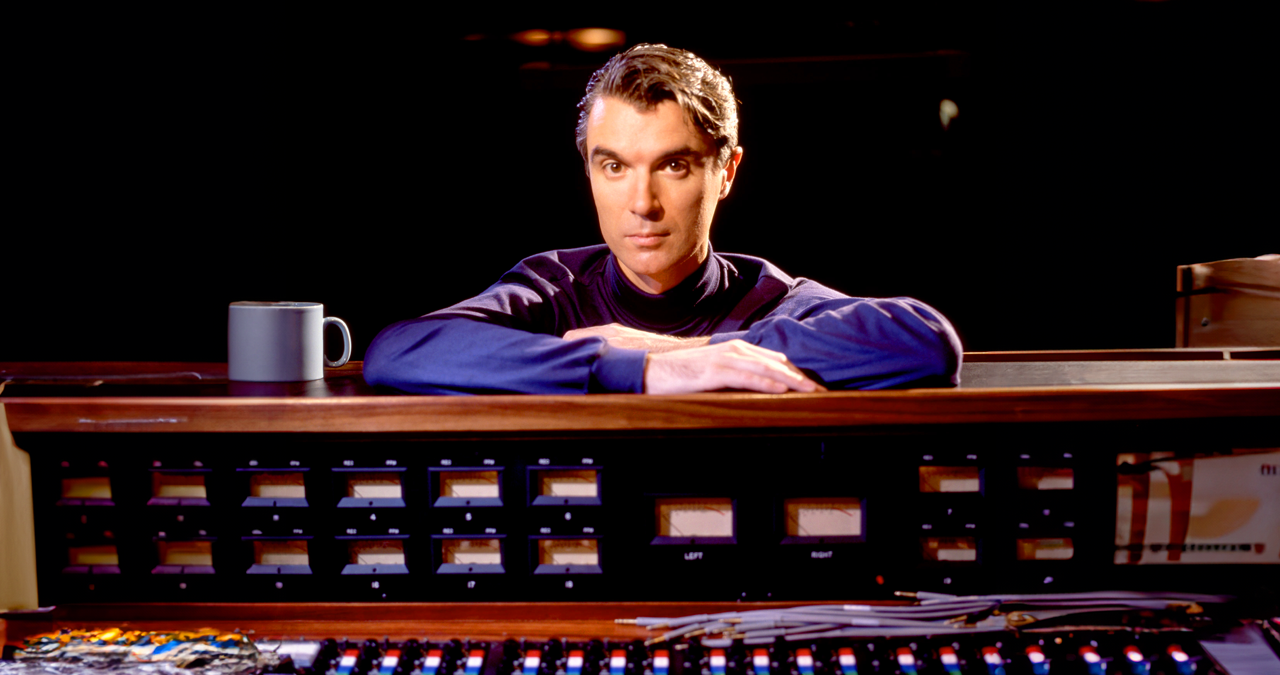

“Making music is like constructing a machine whose function is to dredge up emotions in performer and listener alike”: How becoming more in-tune with our feelings when listening to music made us better creators - with a little thanks to David Byrne

Whether it’s by being exposed to new genres or digging out some of your favourite records - zoning in to how music affects your emotions gives you the best creative blueprint for music-making

Music is a dressed-up form of communication. When you strip away all the reams of theory, dismantle the myriad technical processes and shake-off the daunting mythology of rock and pop, all anybody that’s ever written a song was ever really doing was offering connection to another human being. Often, lots of human beings…

Whether that connection is expressed via a heart-tugging story, making a grandiose statement or provoking an action (typically, dancing), we all want someone to hear, understand and resonate in-step with our music.

Even if we’re telling others (and ourselves) that we’re oh-so very serious artists. The act of expression is itself an invitation to others to respond to what we’ve created.

Everyone wants to be heard.

Whether you’re a professional music-maker, regularly assembling hook-laden tracks and keeping a keen eye on the stream-count, or, if you’re operating in an isolated furrow, and set to release your seventeenth album to a minuscule audience - the basic objective is fundamentally the same.

You're in the business of making others feel something.

While many creatives enjoy absorbing a wealth of artists and genres, how many of them seriously take into account how their enjoyment of someone else’s music can potentially be instructive for making their own?

When immersed in the intricacies of music production, it’s easy to lose our connection with some of those core feelings that might have pushed us into seeking to express ourselves through music in the first place.

That’s why it’s important to listen - and not just to our set influences or go-to favourites - to tracks, genres and soundtracks outside our usual cosy bubble. Noting how the music has been designed to stimulate and manipulate our emotional response.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Beyond this, listening to a wider range of music will expand your musical language, and provide a wider context in which you’re working.

It’s not just passive listening we’re talking about here, nor is it the specific act of active listening from a production point of view (though that is important, and will be covered in an upcoming segment of this series.) But, as with the first two parts in this ongoing music-maker-angled series, we have boiled down the central thrust of this feature into one core lesson…

Lesson #3: Listening to a wide-range of music and tapping into how that music works to affect your emotions will make you a better music-maker

In his seminal book How Music Works, David Byrne, the former Talking Heads frontman, stated “Making music is like constructing a machine whose function is to dredge up emotions in performer and listener alike.”

Yes, Byrne was saying, music is art - but it’s also a technical construct.

And, not just a construct in how a song has been instrumentally performed and thoughtfully produced - but how the artist has designed the track to stimulate, tickle and coax out feelings from listeners.

“Some people find this idea repulsive, because it seems to relegate the artist to the level of trickster, manipulator, and deceiver,” Byrne continued. “They would prefer to see music an expression of emotion rather than a generator of it.”

Byrne noted that, in his view, music-makers are adept at making song elements - or ‘devices’ - that, “tap into our shared psychological makeup and trigger the deeply moving parts were have in common.”

With this idea that all human beings have a fundamentally similar internal wiring in mind, we re-approached how we listened to a wider assortment of music. Some old, some new.

All the while, we pondered Byrne's notion that songs are well-oiled engines, primed to trigger an emotional release. Contrary to the idea that songs have emotions hard-coded into them.

For this writer, who is an occasional music-maker, it has been both revelatory and surprising.

It's reminded, on a technical level, of certain things that when locked in my own practical workflow I’d tended to forget. For example, it's often the light touches in an arrangement that can incite a great deal more than a fully-formed hook or riff.

Listening to an emotionally-affecting piece of music - which managed to wring oodles of emotion from a very simple repetitive fragment of melody - prompted me to approach a track of my own in a similar way, and not to slide into over-complicating the mix. I’ve also been more assured at leaving lengthier gaps within my arrangements, and not being quite so restricted by the rigid orthodoxy of song-form.

The ultimate target is to invite the listener to release their own emotions - to trigger those internal 'moving parts' as Byrne called them. Zoning in on how others work to do that has certainly made me a more assured music-maker. So, thanks Dave.

In the same way that music-making is often trying to follow the breadcrumbs towards ideas you can semi-visualise in your head, active listening in this way (perhaps we’ll call it ‘emotionally-conscious listening’) is an exercise in self-knowledge as much as it is a practical skill, although the insight it can provide on all facets of music-making is massive.

Often it’s certain elements, the ‘things’ in songs that do it.

It could be hook-shapes, vocal performances, the feeling of space, the sly evocation of a totally different song… you’ll feel them when you encounter them.

Rick Rubin expressed his take on this idea (and he too was struggling to define it in words) in an interview with ‘Conversations with Tyler’ podcast; “I think creativity is acts of noticing. Nothing comes from us. The creator isn’t making the thing. The creator is recognising the thing, noticing the thing, and then sharing it in a way where the audience can hopefully get a glimpse of what we’ve noticed.”

It’s understandable that spending hours in our studios or music-making spaces, working meticulously on the nuts and bolts of projects can result in us almost ‘seeing-through’ the music we listen to. It’s also a given that we’ll gravitate towards the music we know we like, and take that appreciation for granted.

Exploring why we like a piece of music can reveal more about ourselves, widen our ability to communicate our creative truths and better empathise with prospective listeners.

So, the next time you’re listening to a track and feel a bit stirred by part of a song, stop and replay it. Pick apart just what’s going on in both the track, and in your own head.

Why did it grab you? Was it the melody, the chords, a lyric - or elements working together in tandem?

And how did it grab you? How did it make you feel?

You'll find that it's often the space in-between the musical information and your own feelings that is where the real soul-touching magic of music takes place.

Learning how to absorb this knowledge into your practice can make the difference from being a hobbyist music-maker to being a truly great artist.

I'm Andy, the Music-Making Ed here at MusicRadar. My work explores both the inner-workings of how music is made, and frequently digs into the history and development of popular music.

Previously the editor of Computer Music, my career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut.

When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.