John Lennon and George Harrison: 10 guitar lessons you can learn from their Beatles era

Songwriting tricks, chord progressions and the guitar genius of the Beatles' early years

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Guitar lessons: Before the chemical-fuelled studio experimentation of their psychedelic ‘middle’ period, The Beatles were a remarkably well-honed hit machine.

Their live-in-the-studio performances were tight, and their songwriting chops even tighter – they reeled off hits with remarkable sophistication for songwriters in their early 20s, with a work ethic that puts modern bands to shame.

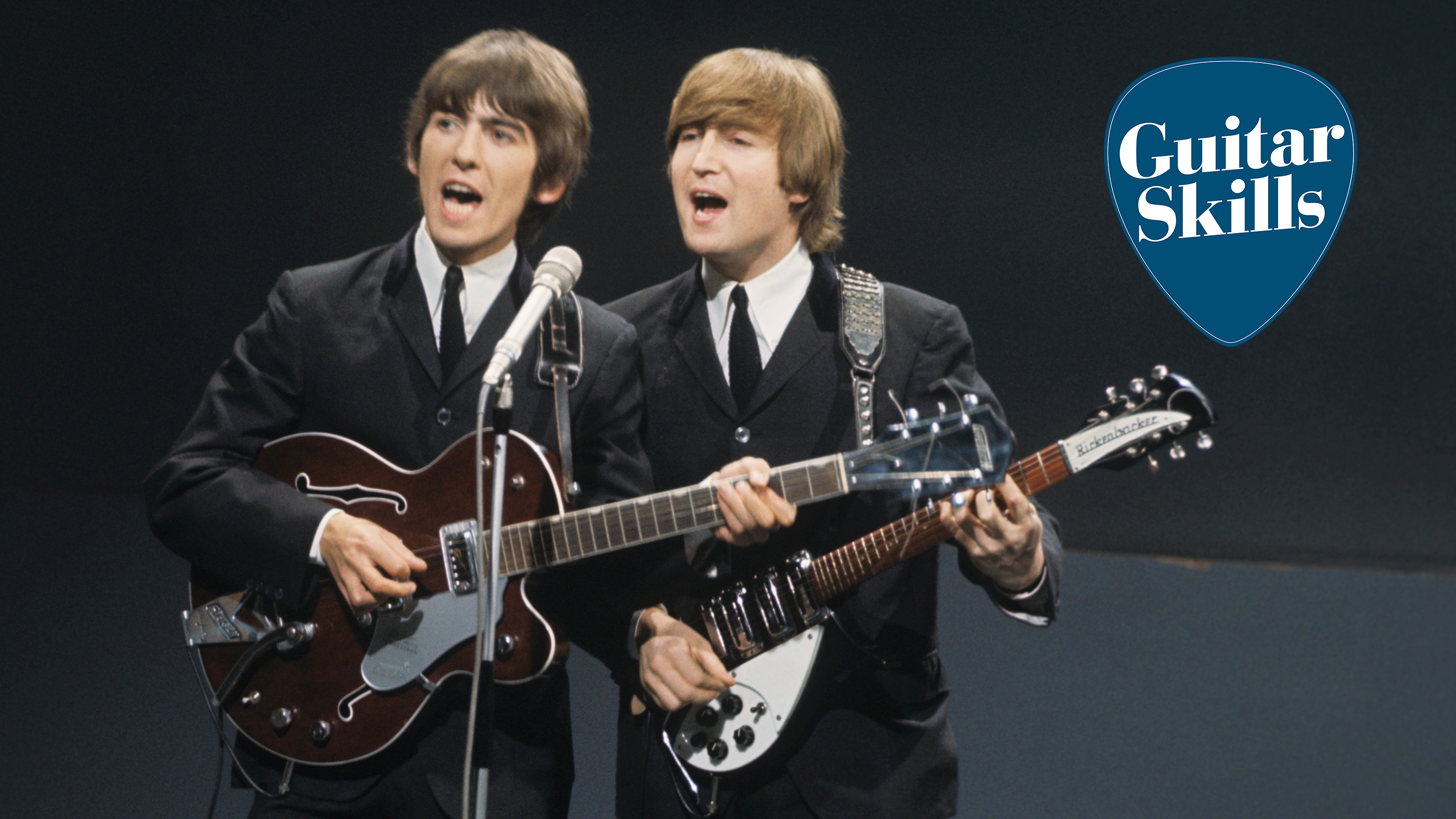

With John Lennon locking down the rhythm, George Harrison’s instantly recognisable melodic lead guitar drew on 1950s influences including Chuck Berry and Carl Perkins, while his early adoption of the Rickenbacker 12-string guitar introduced the world to a sound that is now synonymous with the vocabulary of 1960s pop.

Read on for 10 timeless guitar lessons we can learn from John and George as they burned their names into the musical history books and gained the adoration of millions.

1. The Beatles used minor chords to great effect. Here's five ways you can too:

Make you middle sections minor

A classic Beatles move is to go from a major chord sequence in a verse to one starting on the relative minor for a mood change in a bridge or chorus. Hear it on Misery.

2. It's all relative

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Listen to All I’ve Got To Do and you’ll hear two chords dominating: E and C#m. These are relative major/minor chords. The verse shifts between each chord as the tonal centre, never really settling on either.

3. Stray from the key

Based around E and A chords, the verse in Please Please Me is in E major. However, the break in the middle of the verse ‘borrows’ a G chord from the key of E minor, so the run is: E-G-A-B. It’s a momentary change of harmony and mood.

4. Parallel major/minor

Another classic Beatles move is the ‘parallel’ major to minor change. Try A-Am-E. It’s a basic change from A to E, except that the all-important Am leads you chromatically into the E chord.

5. Work out your relative minors

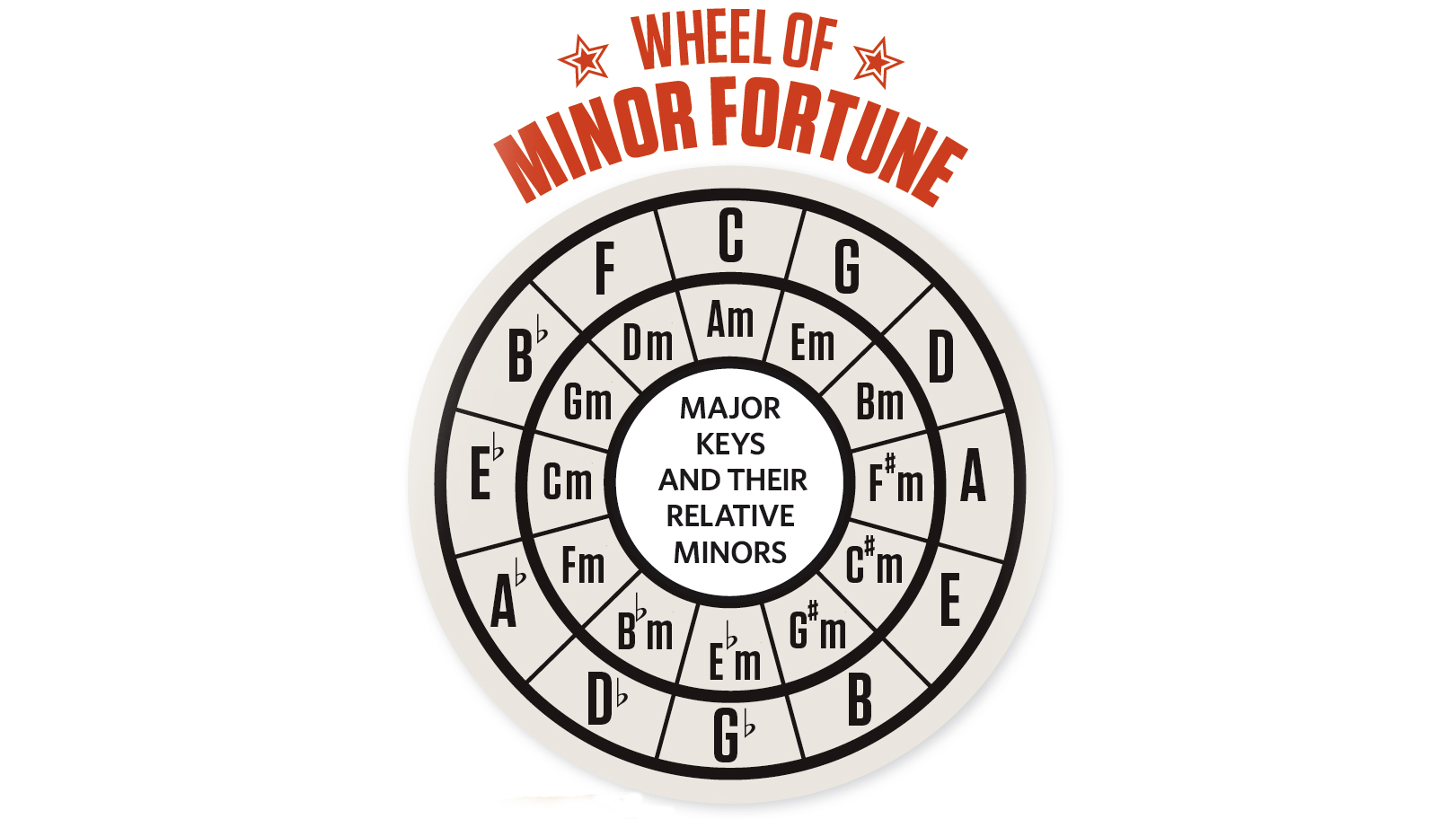

Learning the relationship between major chords and their relative minors unlocks all kinds of musical possibilities. If all of this talk of relativity is fogging your brain, you can use this simple method – start with the major chord of the key that you’re in, and move down three semitones. Or use our diagram (above) to help you.

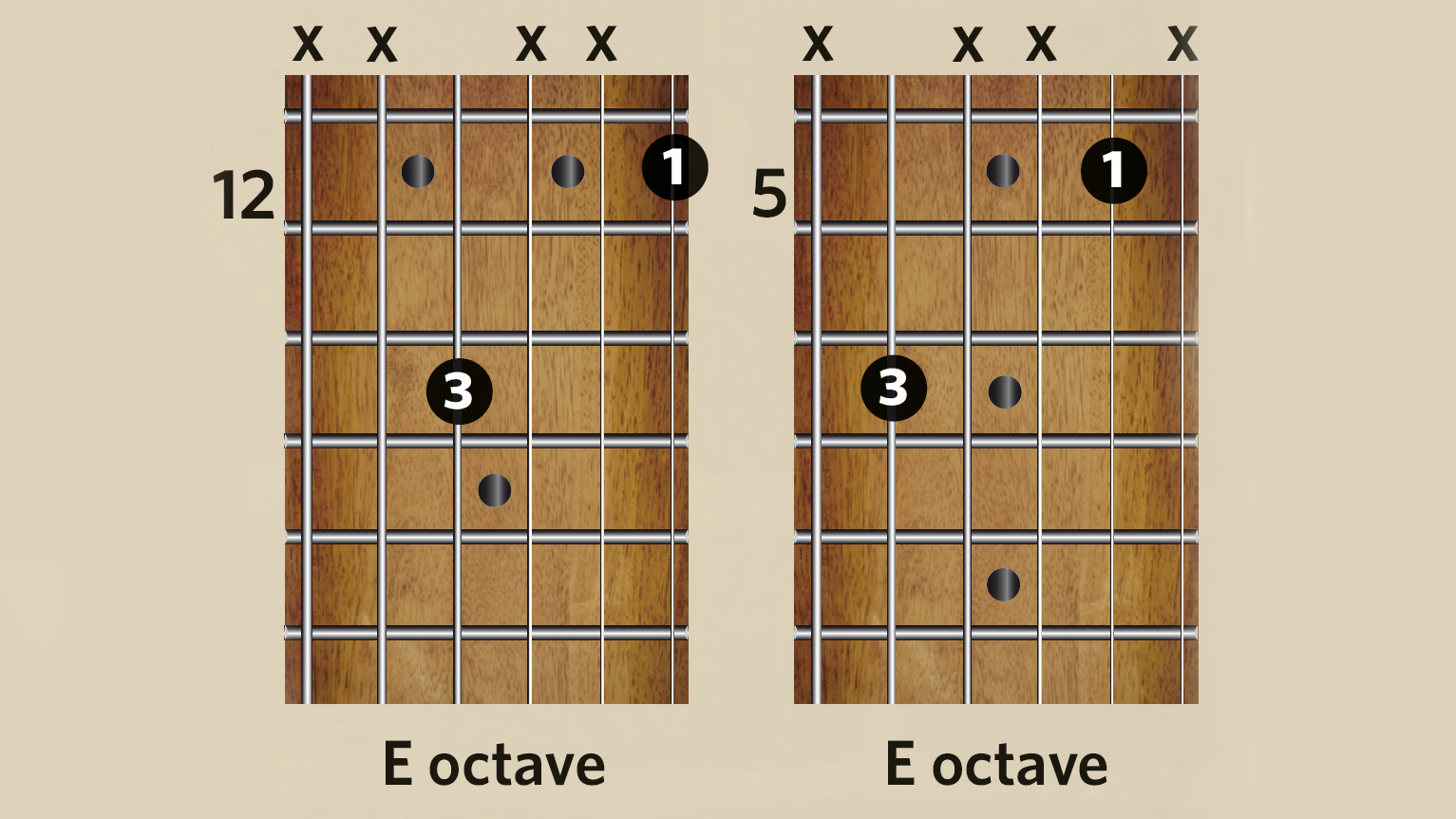

2. George's octave shapes

In songs such as Please Please Me George Harrison would use the octave shapes shown here, instead of the more common shape played on the fifth and third strings.

There is no great benefit to this other than comfort. That said, if you transfer these shapes to a 12-string guitar you will find a different arrangement of the notes in various octaves, so it is worth experimenting.

3. Think around your chords

Outline chords with root notes, arpeggios and two- or three-note chords. The mix of bass guitar arpeggios and two guitars playing partial chords creates a constantly changing rhythm part. Listen to I Saw Her Standing There.

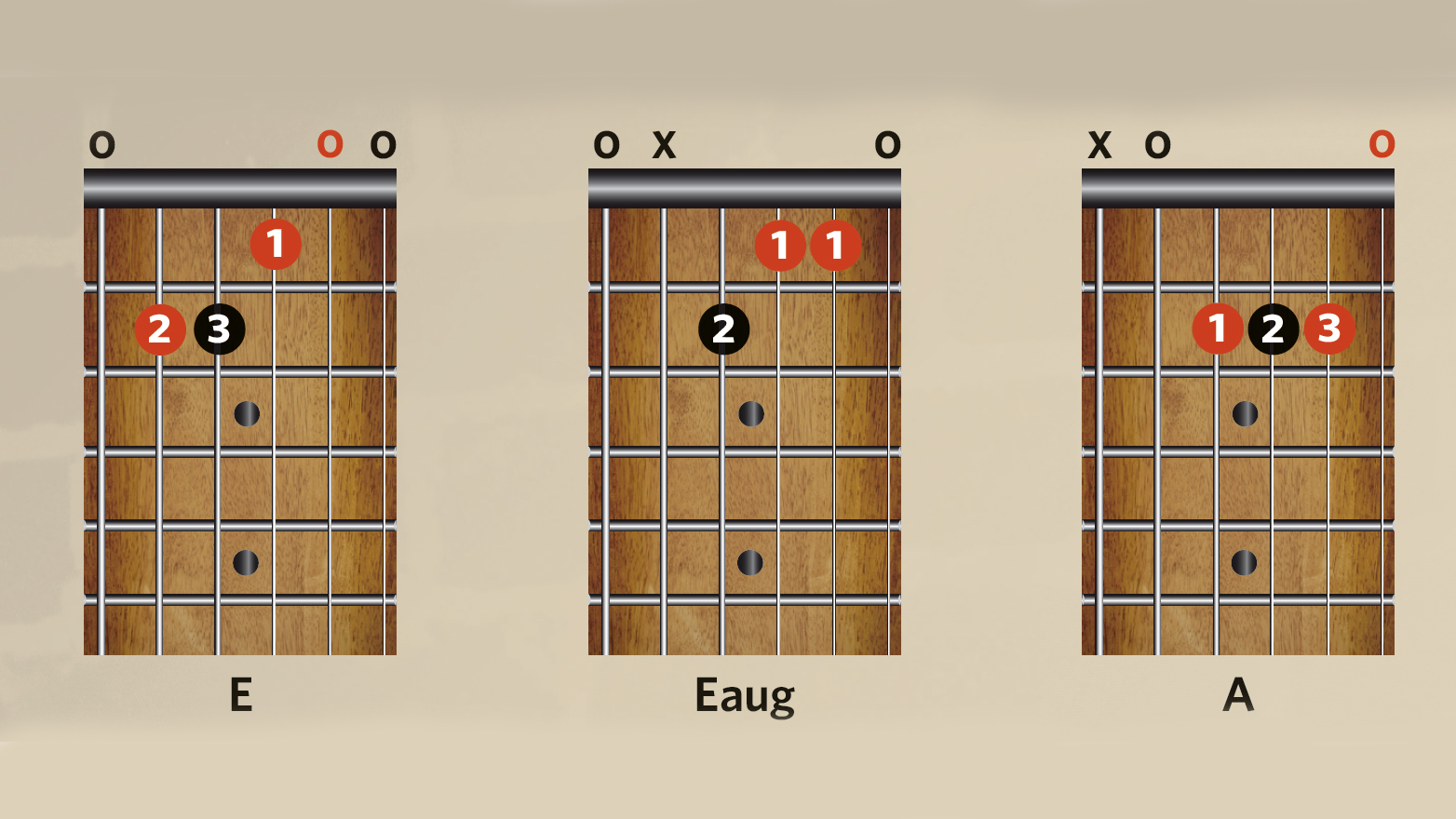

4. Augment your changes

Hang on an augmented chord to emphasise a change. Try E-Eaug-A, as a variation on the basic change from E to A. Ask Me Why is a great example.

5. The I-II-IV progression

It may or may not be fair to say the Beatles ‘pioneered’ the I-II-IV-I progression in Eight Days A Week, but the sequence crops up in their later work, too. You Won’t See Me and Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band are two prime examples of the band’s willingness to return to a musical staple.

6. Using deceptive cadences

In a classic I-IV-V chord progression, there’s always a sense that the V chord should be followed by the I. The effect is called ‘resolving’, and the sense that a musical line is coming to an end is known as a ‘cadence’.

Just play the open chords D7 (the V), then G (the I) to hear it in action. The Beatles would often challenge the listener by deliberately heading off to a different chord after the V.

For example, in Do You Want To Know A Secret, the VI follows the V, giving a sense that the root chord isn’t ‘home’. Try it – start with a I-IV-V progression (E-A-B, for example), and try heading to C#m, F#m or G#m after the B chord.

7. A simple idea can go a long way

Stephen Hill and Michael Gagliano have spent years studying The Beatles’ sound, and have performed as Gorge and John in the Let It Be musical. This riff example of Twist And Shout that they show us proves a simple idea can go a long way.

It's D, G and A chords running through most of the song. Lennon played a slightly simpler part consisting of just the chords strummed with his usual energy and drive. George’s part included the short melody line on the 5th string, and he would simplify the open chords to two-note powerchords.

Stephen and Michael include an extra line that the two guitarists would include in their live shows. This line was based on two-note chords used to outline a melody, rather than being used more generally as chords.

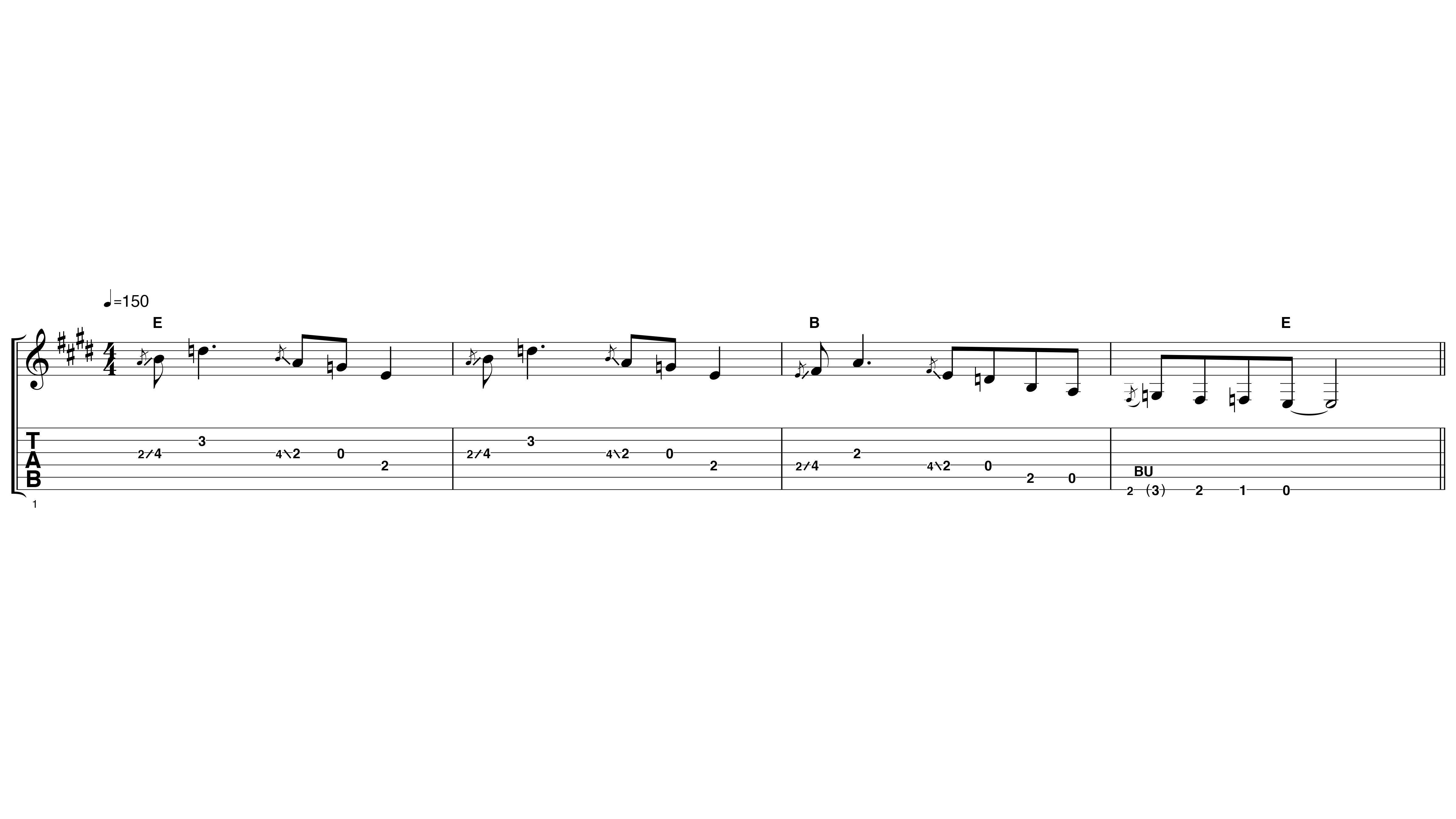

8. George's transposition of pentatonic ideas

By working out the licks of American blues guitarists, George realised that the minor pentatonic scale could be transposed to ‘fit’ each chord in a 12-bar sequence.

The opening E minor pentatonic lick in this example is transposed down a 4th so that it can be repeated over the B chord in bar 3

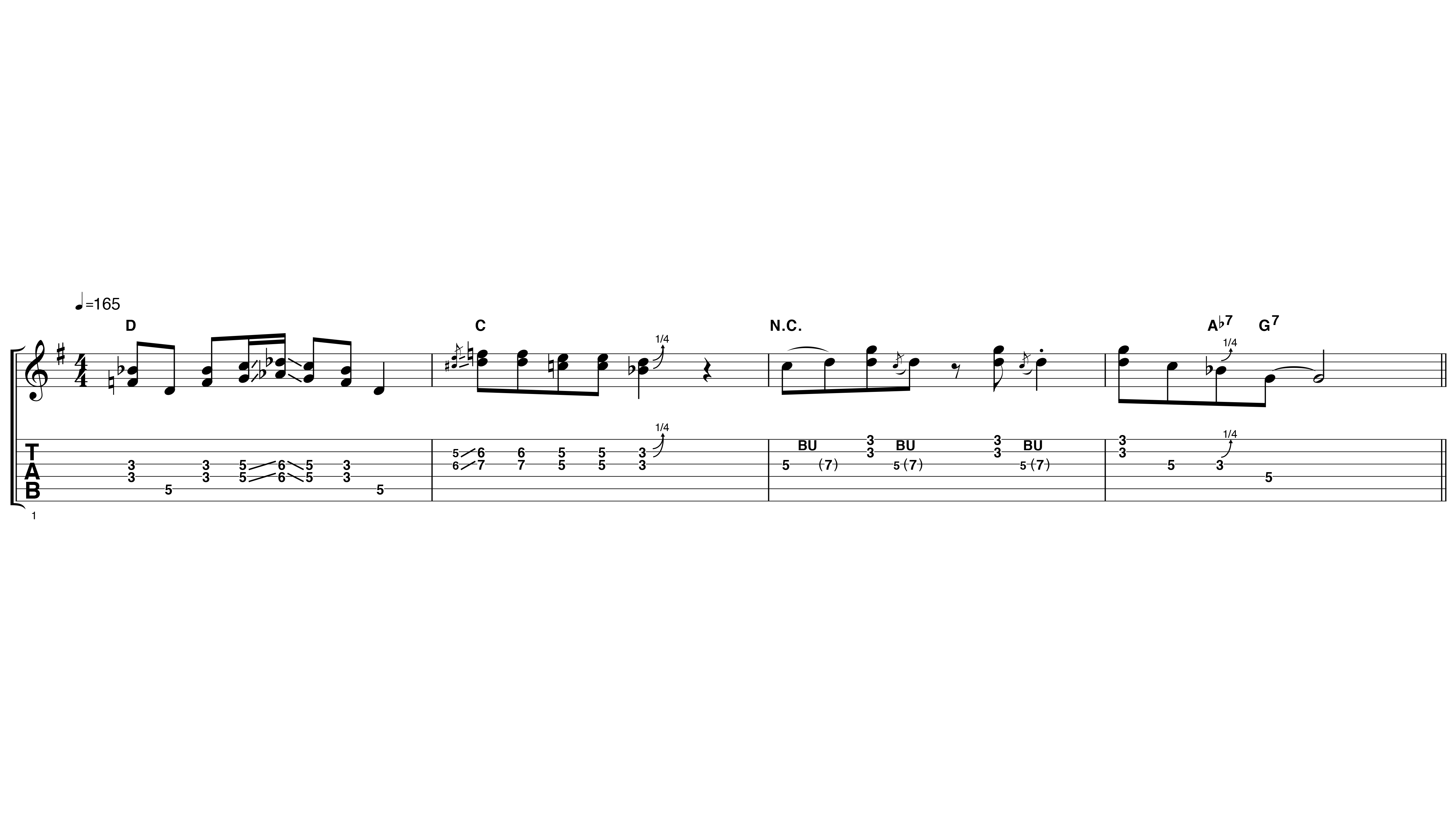

9. John's Chuck Berry-inspired soloing

John Lennon didn’t play many solos in the early days of The Beatles. However, one of his best-known solos comes on Long Tall Sally, originally a Little Richard tune.

Our example showcases doublestops (two-note chords) and raucous string bends.

10. Contrasting guitar parts can complement

Stephen Hill and Michael Gagliano again show us a famous riff; this time it's I Saw Her Standing There, and the two guitar parts are quite different.

John Lennon’s part is a steady, chopping rhythm using a shape based on an open C7 chord, but which is moved up a few frets to make it an E7. The trick is to stab those chords while repeating the open sixth string underneath.

George Harrison’s part is based on a different voicing of the E7 chord – an open D7 chord moved up two frets. More importantly, George adds single notes into these intro chords, and also mixes chords and a rock ’n’ roll-style arpeggio during the verse.

Guitar lesson: learn 4 fab Beatles chords (including A Hard Day's Night)

Total Guitar is Europe's best-selling guitar magazine.

Every month we feature interviews with the biggest names and hottest new acts in guitar land, plus Guest Lessons from the stars.

Finally, our Rocked & Rated section is the place to go for reviews, round-ups and help setting up your guitars and gear.

Subscribe: http://bit.ly/totalguitar