3 ways to come up with a melody from scratch

As the track element that you often most want the listener to remember, your melody has to be on point. Read on and it will be…

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A mainstream track won’t get very far if it doesn’t have that special something - that unique element that a listener can grab onto and remember. Something that’s familiar, yet new. A hook, essentially.

Your tune’s hook could be a vocal phrase, a repeated melody, or even a funky beat, and here we're looking at melodic material.

So what makes a melody? We’ll start off with the basics. Simple melodies (and even plenty of complex ones) tend to start and end with the ‘tonic note’ - that’s the note that starts the scale you’re in, such as C in C major, or G# in G# minor.

But you can’t just use one single note throughout! A melody is also about moving away from that note. Without wanting to sound too airy fairy, it ‘tells a story’ by starting at the tonic note, moving away from it, then finding its way back at the end. Of course, it’s the journey that counts, rather than the destination.

Melodies also tend to make use of phrases. Over four bars, you might encounter four separate phrases, with gaps (or at least less action) in between them. These phrases are often linked in some way musically, acting as ‘call and response’ pairs, or ‘question and answers’ pairs, if you prefer to think of it that way.

Fifth amendment

Another handy rule of thumb is to end your middle phrase (halfway through the melody line) with the ‘fifth’ note. This is the fifth degree of the scale - ie, seven semitones up from your scale’s tonic note: the G note in the C major scale or the A# note in the D# minor scale. We won’t get bogged down in the details, but this reinforces the listener’s urge to get back ‘home’ to the tonic note by the end of the melody, and helps it all make a lot more musical sense in general.

But these basic melodic rules leave a little something to be desired. They apply to easy ideas such as nursery rhymes, but the real art in modern music is to mix things up a bit - to subvert the listener’s expectations. Once you’ve learnt the building blocks of melody, it’s time to break the rules and hit the listener where they least anticipate it: use unusual rhythms, unexpected turns from note to note, and never-before-heard sounds to get deep into your audience’s skulls.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Even then, though, go too far with your musical experimentations and you’ll risk alienating everyone. It’s a fine balance to strike, but that’s what being a musician is all about.

Here are three tried-and-tested ways of constructing ear-catching melodies. For more on the subject, pick up the Autumn 2018 edition of Computer Music.

1. The rhythm-first method

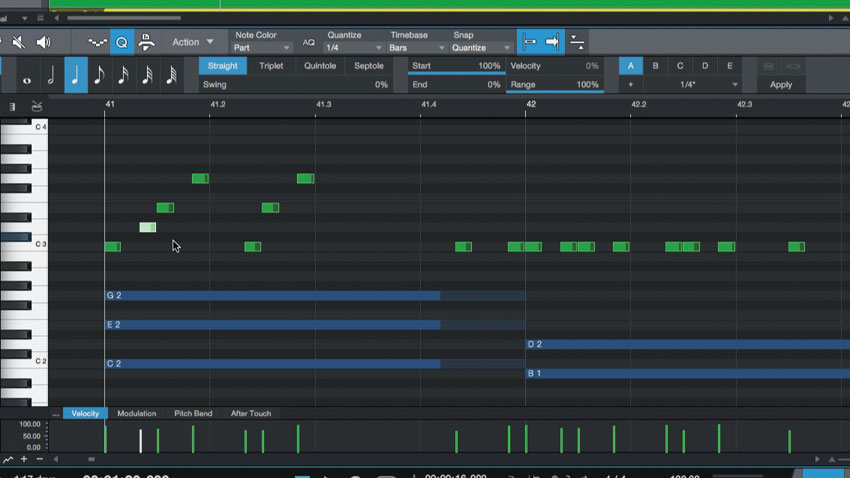

Sometimes, laying out the rhythm with one note helps you get started, and from there, all that remains is the final 50% of the task. Experiment with different notes in the already-interesting rhythm you’ve laid down, and it’s hard to go wrong.

Our project is a great example of building a melody with this method. As we’ve laid down the whole thing using just C notes, with the rhythms already programmed, all we need to do is move the notes up or down. There’s still plenty of refining to do though, of course…

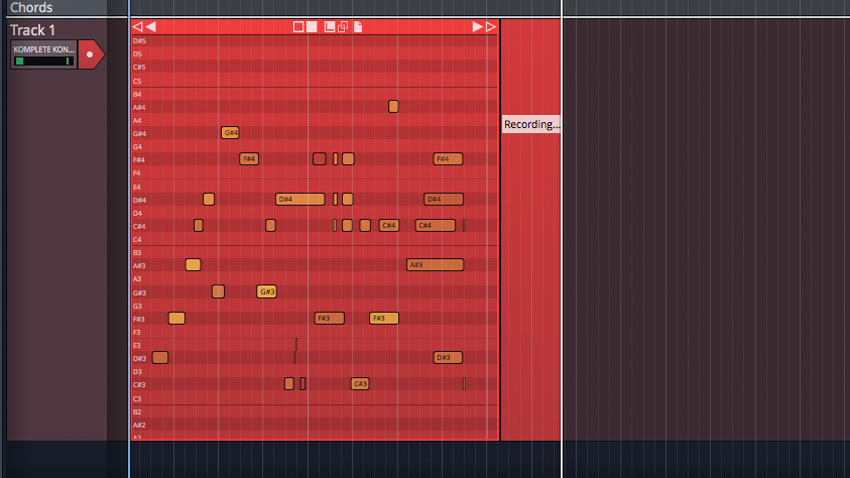

2. Recording then editing

It’s not all about textbook theory. Set your music to loop, work out the scale you’re in (and therefore the notes you need), and get down and dirty with your MIDI controller. Even if you’re not Mozart, there are very likely to be salvageable snatches of inspiration in there. And with the magic of the modern DAW, you can experiment with what you’ve recorded, then tweak to improve your result. Hint: duplicate melody clips before changing them to give yourself a variation to use later on!

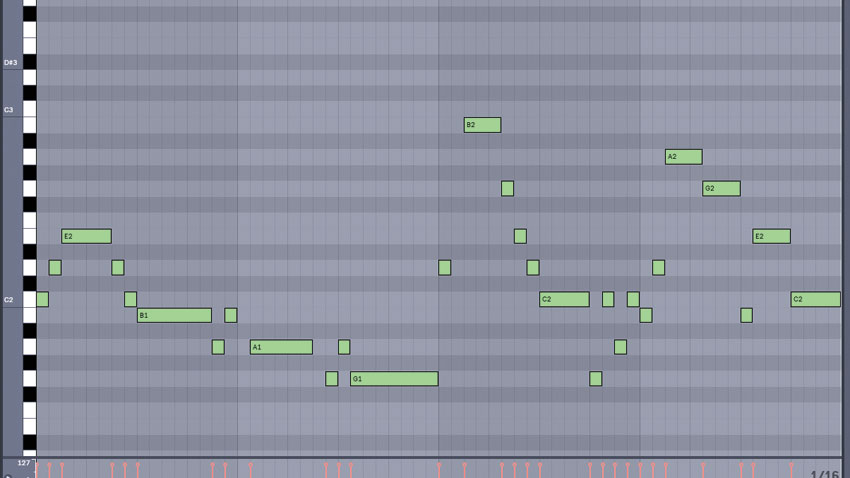

3. Ramp up the contrast

If melodies are a fight between something a listener’s heard before and something they haven’t, then one great weapon for the ‘unusual’ side of the equation is contrast. Moving in smaller steps rather than big leaps is usually standard, but making large jumps between notes will help your melody stand out against the crowd.

On a similar tip, treat your melodic phrases in the same way: if you’ve just gone up to higher notes, go down to lower ones next time round. If you’ve just played a phrase full of short, staccato notes, go for a lingering section of longer, held notes to slow things right back down. In the search for something interesting, contrast is king.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.