How to write a hit: melody

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Along with the lyrics, the sung melody makes up what is known as the 'topline' of the song. Some writers are renowned topline experts and tend to be called in to help complete a song or to craft a topline for an existing piece of music.

The topline is the most important aspect of any conventional pop song - music without a topline is not a song, but as anyone who's ever belted out a tune in the shower knows, a topline without music is.

When writing a melody it's best to use short phrases that link up to form bigger lines. Short phrases of between two and seven notes are much easier to remember after one listen.

Using two or three simple phrases, repeated, transposed and juxtaposed can deliver a memorable, original and powerful melody (as shown in the Somewhere Over the Rainbow example to the right).

A good melody doesn't have to move around all over the place to be interesting. Sometimes a relatively monotonous melody can come sparkling to life with the addition of some strategically placed melodic 'spikes', the position of which can often be determined from the natural stresses of the lyric you are using. Of course, there are always exceptions to these rules that become fleetingly successful, but they probably won't go on to become classics.

Lady Gaga's "I'm going to ma-rry - the night" is one example - the stress on "rry" is completely unnatural.

The melody should do different jobs according to where it is placed in the structure of the song, and we will look at this in more detail later on. Generally, the melody will hook you in and gradually build somehow, either in pitch or rhythm, towards a simple and powerful chorus, which should be the apex of the song's energy.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Some great sources of inspiration are playground and military chants. There's also a load of classical music (now out of copyright) that makes an amazing untapped resource for fantastic melodies - listen to Mika's Grace Kelly (harmony from an aria in Rossini's Barber of Seville) or Jem's They (Bach's Prelude in F Minor).

Overcome creative blocks by reversing a melody, or changing the chords underneath it; changing scales and modes can be also very helpful in creating moods and feelings. Remember, the melody must be catchy!

To the right we've provided four examples of simple but infectious melodies with an explanation of why they work, simplified and exaggerated for clarity.

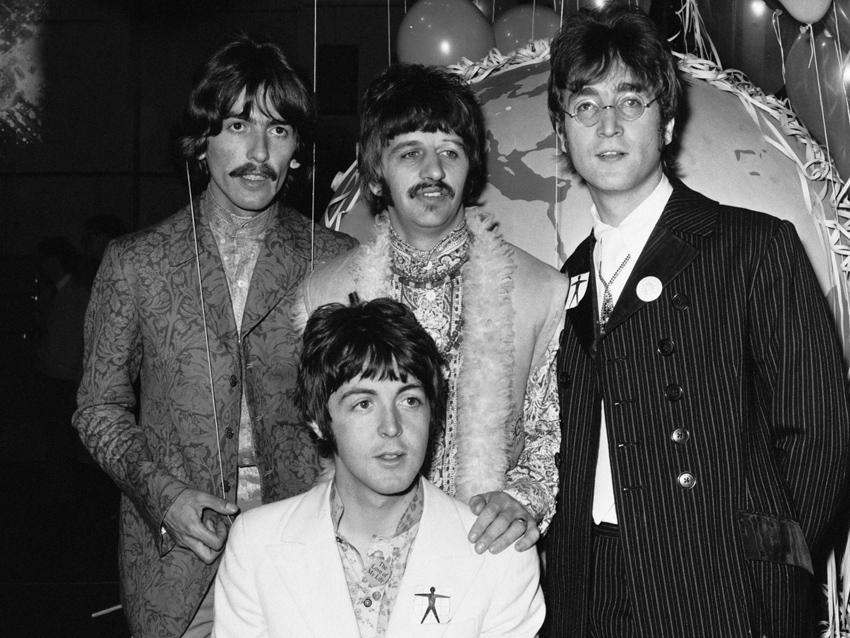

Four simple classics

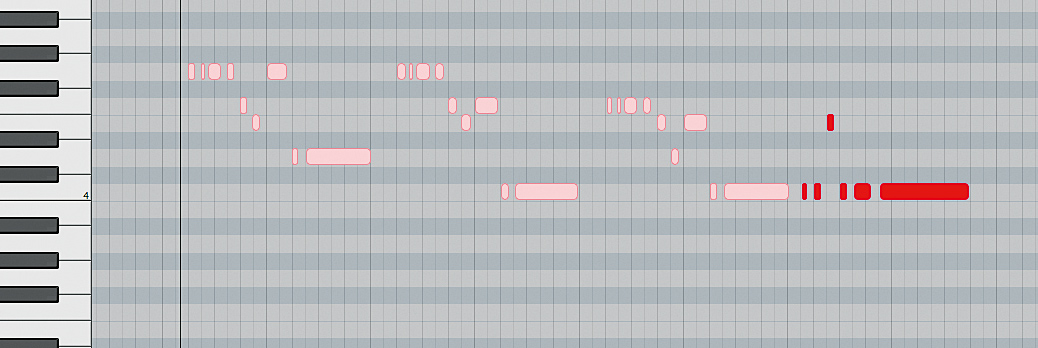

Peaks and constants: Ed Sheeran - A Team

After a simple verse constructed of repeated two-note phrases, the melody begins to set up a tension before the chorus. "And they say / She's in the class A team / Stuck in her daydream" - it's the peaks on the stressed syllables that give this otherwise monotonal passage all its energy. On the piano roll above, the peaks are in red.

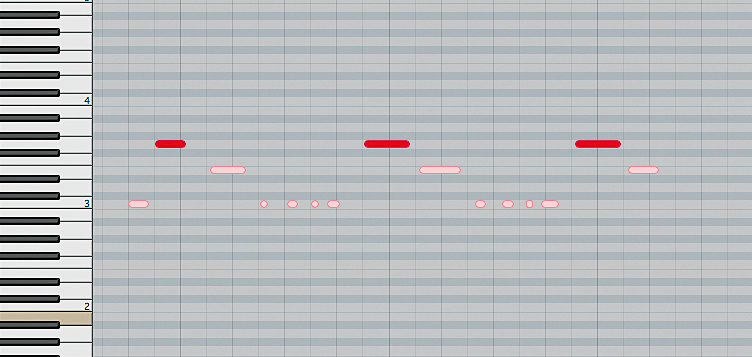

Repeated figures and symmetry: Arlen/Harburg - Somewhere Over the Rainbow

This awesome melody is a lesson in simplicity. It essentially comprises only two phrases. One is a huge two-note interval from low to high; the other is five-note phrase where the beginning note is followed by a four-note ascending scale that arrives back at the beginning note again. The two phrases are coloured differently on the piano roll above.

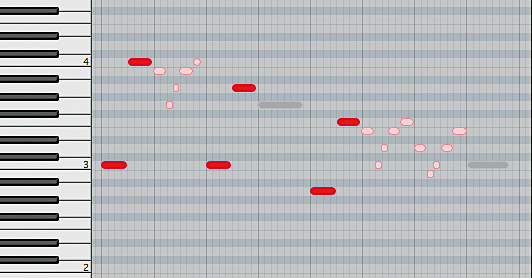

Constant note/moving chords: Lennon/McCartney - All You Need is Love

This classic melody is so simple it's arguably not a melody at all, but the musical elements contextualise it, and the lyric "All you need is love" gives it its power. You can see the underlying chords shift, though the melody remains monotonal. The chromatic brass riff punctuating the phrases emphasises the power of the hook while providing contrast.

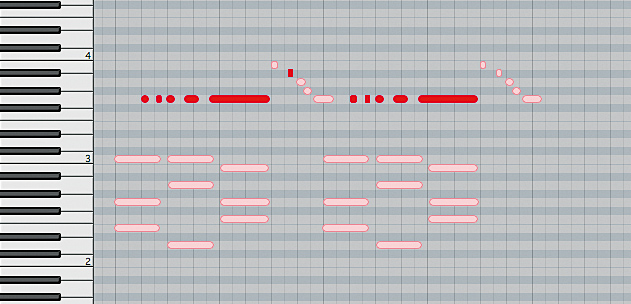

Mix of repetition, monotonality and peaks: Bob Dylan - Make You Feel My Love

In this fantastically simple song, Dylan has used a single figure repeated three times, each with a small variation to accommodate the changing chord beneath. The final phrase is a monotonal series of notes with a peak in the perfect place, though it's arguably fair to say this peak was chosen for its melodic position rather than for the lyric it emphasises.

For all the advice that the recording singer-songwriter needs in 2012, check out Computer Music Special 52 - the Singer-Songwriter Production Guide - which is on sale now.