Trevor Jackson: "Some of the best things are made when you switch off your thought processes and just do it"

After a 30-year career and a period of introspection, we find him clearing the decks for new material

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Designer and producer Trevor Jackson began his career in the music industry managing a record store and designing record sleeves. In 1987, he formed the design company Bite It, working for large corporate clients and labels alike until his love of electronic music and hip-hop ignited a passion for production. As the Underdog, Jackson worked on numerous self-penned releases and remixes for the likes of Massive Attack, U2 and Unkle, leading to widespread industry acclaim.

By the mid-’90s, Jackson had created the post-punk dance act, Playgroup, with collaborators including Edwyn Collins, Scritti Politti and dub master, Dennis Bovell. He then formed Output Recordings, launching the careers of Four Tet and LCD Soundsystem. However, sidelined by his label work, Jackson began to feel irrelevant as a producer. Thankfully, the process behind System, the final release on his archive label Pre-, has Jackson fizzing with ideas again and ready to produce new music.

You have a huge vinyl collection. Are you still using your records for sampling?

“At the beginning, everything was sample-based, so I did buy a lot of the music for sampling, but I’ve learned so much about music by digging for things. I was a massive Adrian Sherwood, Trevor Horn and Arthur Baker fan and bought every single record those guys made. To this day, I’m not really a musician, but over a 30-year period I’ve taught myself how to form music without using samples.”

It’s interesting you bought music by producers…

“It wasn’t just producers; I’d pull a record out and look to see if there was a drummer or synth player I liked. I worked in Loppylugs Records in Edgware, and you’ve got to be a bit of a nerd to work in a record shop, but it’s not like I was into catalogue numbers and stuff. I had a design career, so I got into looking at the credits more from looking at the sleeve designs first. The ’80s was a highly productive time for music, mainly due to the technology that was emerging, and I slowly gravitated towards the people producing the tracks.”

Do you miss the design aspect now that vinyl is not the dominant format it used to be?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Although I like the past, I embrace the present. There are less record sleeves, but there are more websites and videos. The visual representation definitely adds to music, but it doesn’t have to be on a 12” piece of card. I’m a big fan of CDs actually and listen to albums more on that format.”

With a passion for design and your own design company, how did music become your career path?

“I was always making music in my bedroom. I had a little four-track recorder and a Commodore 64 sample module and put some tracks together. I entered a Morgan Khan Street Sounds competition - a UK hip-hop thing, which consisted of very simple beats mixed with spoken word TV samples. Then I got a Roland W-30 sampling sequencer.”

We were aware people used the Atari console to make music but not the Commodore 64…

“I did use an Akai 950 with the Atari ST - as a sequencer/computer combo it was rock solid, but with the Commodore 64 you could click in this SFX Sound Sampler. It had 1.4 seconds of sample time, so I could sample a kick, snare, hi-hat and clap, and everything I did sounded like the Art of Noise track Beat Box. Then I used a Roland W-30 sampling workstation before moving on to the Akai samplers.”

So you were designing sleeves and producing?

“I was designing record sleeves from the mid-’80s and making music in the background. By 1993, I was doing four or five sleeves a week and working for Pulsate, but wasn’t really enjoying the records I was designing. At that point, working in the record shop with me was Richard Russell from XL Recordings. He was my Sunday boy; I’d tell him to put the grills up and sweep up, but when he started working at XL he asked me to do a remix for the American hip-hop group, House of Pain. I did this remix and the version went top 10 and got a gold disc, so my music career took off from there.”

Did you ditch designing sleeves at that point?

“I was designing sleeves for Gee Street Records, artists like Stereo MCs, PM Dawn, Jungle Brothers, De La Soul and Queen Latifah, but when Jon Baker, who ran the label, realised I’d started making music, he asked me to do remixes for Gravediggaz and a few other people. I still did a few design things but I really embraced production and remixing and became this character called Underdog.”

What studio were you using back then?

“When I first started making music I worked at Monroe Studios in Barnet before it moved to Holloway Road. That was the epicentre of London hip-hop and drum & bass. Lucky Spin Records was next door and there were two engineers there, Pete Parsons and Roger Benu, who worked on so many of those amazing early records. They had a shitty Soundtracs desk and everything went through that and some LA Audio compressors.”

Did you work alongside musicians in those days?

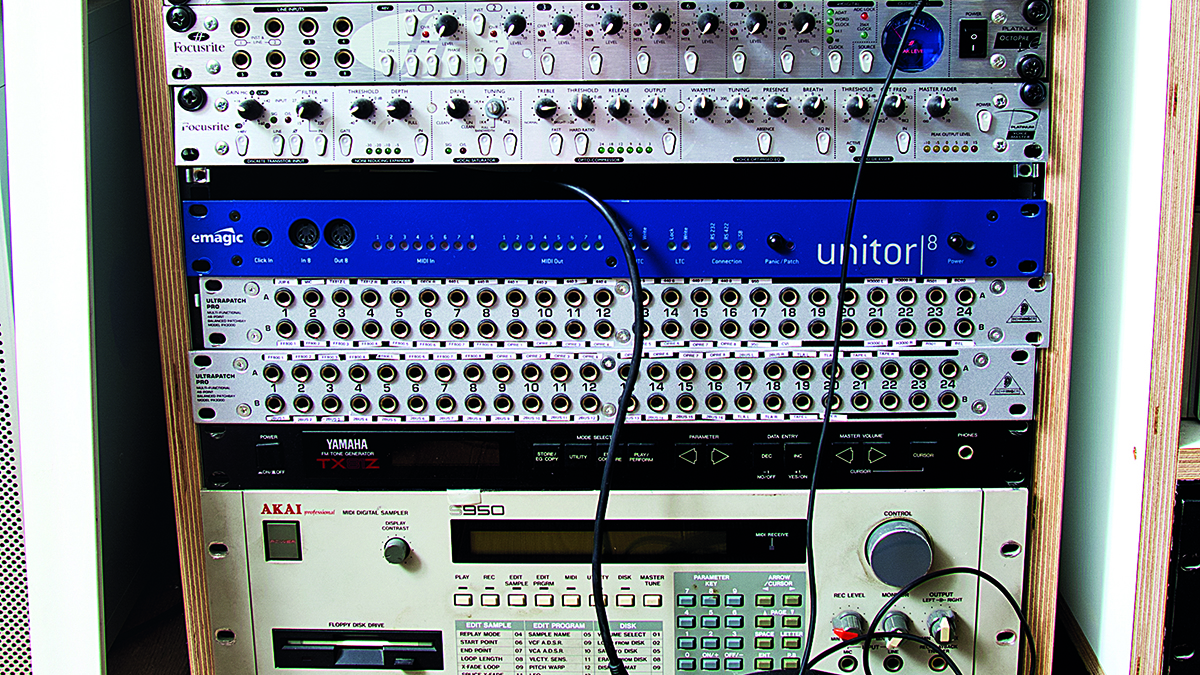

“I worked with Edwyn Collins, who had an incredible collection of vintage gear, and loads of other musicians, but even then I’d just sample them and put everything through an Akai S950 sampler. There was just something about the way it sounded. I’d do the sequencing on an old Mac, but it couldn’t record any audio. Then I started getting bass players in and bought an Oberheim OB-Xa synthesizer, which I’ve still got. I also had a Jen SX-1000 monosynth and started buying drum machines. I’d use the S950 for the main body of the track and enhance things with samplers and drum machines.”

The S950 was an important piece of gear for you…

“Nearly all the music I’ve put out was done on two Akai S950 samplers. I’d put the drums and the bass through the mix output so I could compress them in a certain way and used the eight outputs on the other one to record separate elements. I eventually got an Akai S3000. The mono out would go through the compressor, which made everything pump.”

When sampling musicians, how did you avoid breaking up the feel of the performance?

“I was never recording virtuosos. The sampler could only sample for 30 seconds, so I’d just take loops and phrases. I’d get a bass player in, but my brain was always thinking in terms of breaks. Around that time, I did an album for a band called Emperors New Clothes on Acid Jazz, which never came out. There were four musicians, but I took every track - the kicks, snares and hi-hats - chopped them up and reconstructed them through the S950. It wasn’t easy, but that’s what I felt comfortable doing.”

Then you moved to home recording?

“When I realised I could make music at home, I got an Akai MG1212, which is an incredible 12-track desk. It had parametric EQs and a Betamax-type tape machine that you could record onto. I think DJ Shadow used one and Pete Rock & CL Smooth used a cassette version of it. I adore that machine.”

Is that when you started to build up your studio?

“Yes, but some bad shit happened and I had to live in a lot of different places for a while, so I was carrying gear around with me to record and make music with. I only moved to this studio about five years ago, but the MG1212 desk broke and I wanted to get myself a good analogue desk. I spoke with John Oram who designed Trident EQs and that convinced me to get an Oram T-Series desk.”

Is using a desk superior to working solely in the box?

“I love the sound that you get from a demo recording, but as you progress in your career you can easily lose that naivety and I never wanted to become so polished that I lost the vibe of things. I need things to be processed through real EQs - I just think there’s a magic to that. Even if I work on a laptop I’ll record stuff through the Oram, edit it in the laptop and bring it out to tape or back through the desk just so it exists in the physical realm. I still bounce stuff down to metal tape all the time because I used to love how records sounded on the radio. There’s something about that second or third generation sound; it’s not about warmth, it’s more about character and personality. The joke is, most of the gear I’ve got in here I haven’t used that much. I set up this studio, but I didn’t want to use it properly until I finished releasing all the old music I’d made.”

Hence your latest album System; what’s the story behind releasing old material?

“I stopped releasing music after my label Output closed in 2006. Various things in my life happened and I wasn’t in the right headspace to release music even though I was still making it. In 2015 someone from the Vinyl Factory came to see me and asked if I was interested in doing a project with them. I’d lost confidence having been out of the game for so long, but they loved the stuff. I wasn’t sure about it as it didn’t meet my standards. I had about 200 unreleased tracks, and that’s when I came up with this concept of every track having a different format and using them for installations and exhibitions. That went really well and triggered me into thinking this stuff was actually quite good, so I’ve been going through my whole archive over the past three years and releasing it. System is the sixth and final release.”

Has working in isolation contributed to your lack of confidence during certain periods in your career?

“A few things happened to me to change my opinion about my place in the world of music. I was always very fortunate that my work was recognised when I started and it sold. Sales weren’t necessarily massive, but I had respect from my peers and people I wouldn’t have expected.

I literally thought my music was shit and didn’t make sense anymore.

During the time I ran Output, I was working with guys like Kieran Hebden and James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem - producers whose work I thought was incredible. I made a conscious decision to step back and didn’t have time to make music, but they also had an impact on me because I started thinking, shit, these people are much better than I am. I literally thought my music was shit and didn’t make sense anymore.”

How did you get through that?

“When a close friend of mine died, it really shook my life up and music actually got me through it. Some of the tracks I’ve recently put out have evolved over 15 years, starting out as rough demos. I didn’t have the sessions anymore; I only had the stereo files, so I edited them and added stuff on top, which was quite a cathartic process. It took Sean from Vinyl Factory to come in and a few other people to make me think there was some worth in it.”

With the new music you’re about to produce, are digital tools coming more into the fold?

“I’ve got more into editing, but I’m still running Logic 9 on an old tower, which has never crashed. I use it mostly as a sequencer and I’ve got Logic 10 on the laptop running as an editor because the audio capabilities are better. For me though, the Emagic version of Logic is better for sequencing; it’s so tight.”

How do you plan to make music going forward?

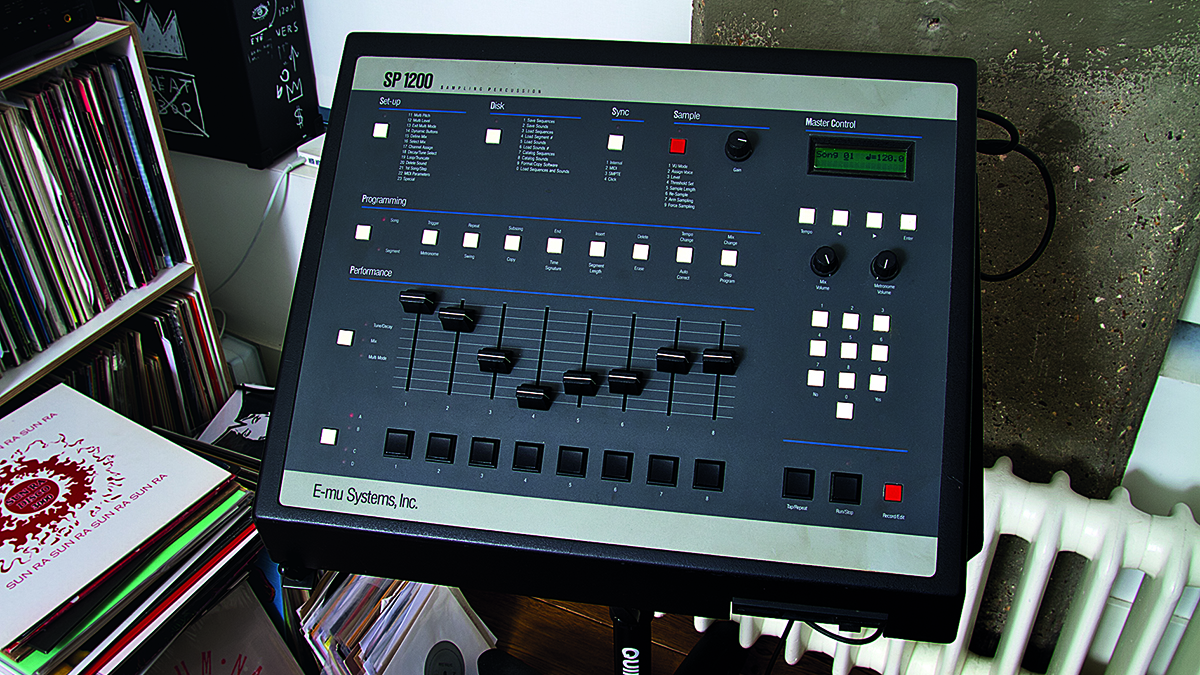

“The forward plan is not to use a computer for sequencing at all, but use my SP1200 as a master and try to run all my gear live. I’m also trying to get hold of a Fairlight CMI Series II and make some crazy music with that. To me, it’s probably the most iconic musical instrument of my generation and the sequencer is beautiful. I just adore sampling sound. I’m happy to use a computer for editing, but not sequencing. It’s ridiculous to say, but up to now the music-making process has been really hard because I’ve associated the struggle with getting a good result. I’d like to change my ways and just enjoy it more; I want to keep that essence of naivety.”

You’ve not got into modular?

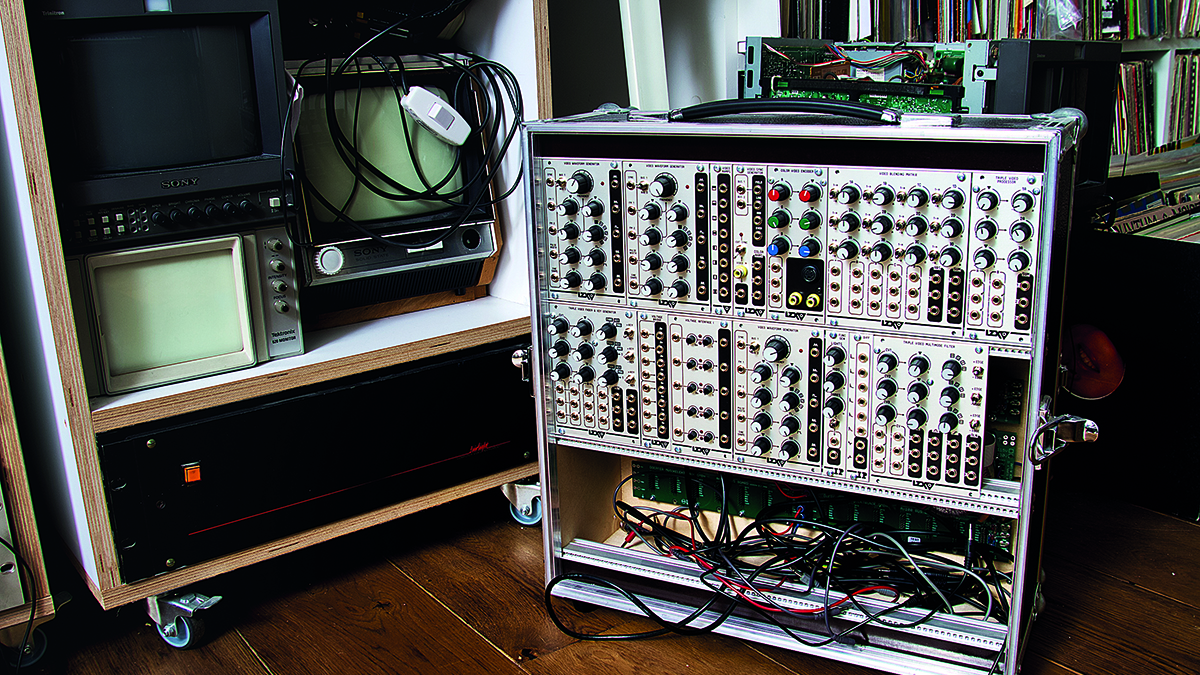

“I’ve got this modular video synthesis system, but didn’t want to get into the audio side because it’s just a black hole. Having said that, I’ve got a Roland System-100 – it used to belong to Genesis because it has their tour sticker on the back. I didn’t buy the unit in one piece; I found the speakers in LA and had to search for the separates. I’ve added a mixer with a spring reverb, a sequencer and an expander. This, along with the MiniKorg 700s is what The Human League used to make Being Boiled and Daniel Miller on Warm Leatherette.”

You’ve retained a curiosity surrounding how those records were made, and want to use the same gear?

“To me, they’re icons of the 20th century. I’ve got a Roland Jupiter-6 because Larry Heard used it on Mr Fingers and Fingers Inc., the Roland TR-808 of course and the Elka Synthex as it’s got the laser harp that Jean-Michel Jarre used. This Linn LM-1 drum machine was handmade by Roger Linn; the sound of it’s incredible because he sampled a live drummer and put in onto the chips. A lot of my favourite records during that period were made on it. But I’ve stripped things down. I’ve got two polysynths and a couple of monosynths and I do like early digital stuff too. I’ve got the Simmons SDS6 and SDS7 – incredible sequencers that use cards with chips on them. You programme them via dot matrix.”

Is there any room for soft synths and VSTs?

“I’ve got the UVI Vintage Vault synth collection, which is fantastic. It has copies of every synth and drum machine ever, even Fairlights and Synclaviers. It’s probably the best-sounding vintage software I’ve heard. Recently, I had to do a remix really quickly while I was travelling, so I did the basics on that then combined software with hardware.”

Where’s the innovation coming from these days?

“Being the age I am, I’ve gone through a convoluted thought process on this subject matter. When I was younger, to make the music you had to have an extreme passion to find out what gear you needed, save up to buy it and learn how to use it. There was no YouTube and just a few magazines. You had to speak to people, so to hunt down that gear was a huge part of the process. That means the only people making music were those who were really passionate about it. They weren’t making wallpaper music; every piece of music that came out was for the right reasons. Now, the democratisation of the whole thing means anyone can make music.”

You’re against the democratisation of music?

“What’s most important for me is the reason someone makes a record. Part of me thinks some of them don’t deserve to make music and shouldn’t be making it just for the hell of it because they didn’t have to go through what I did. I’m a man that’s never used a sample CD in my life or a fucking library. Every track I’ve ever made came from drum machines I bought and sampled. It sounds lunatic now, but if it wanted a 909, I bought it, sampled it and sold it.

Every track I’ve ever made came from drum machines I bought and sampled. It sounds lunatic now, but if it wanted a 909, I bought it, sampled it and sold it.

That whole mentality that you can get a CD with 20,000 sounds on it is sacrilegious to me, but on the other side I’ve also learned that music is about expression, and it’s great that anyone can pick up something and express themselves. Maybe music has a slightly different purpose now, but I think it’s good that a ten-year-old can learn GarageBand and make a track. I guess the new me is coming round to the idea that everything is valid, whereas before I thought the process was more important.”

Would you also say it’s less important how people approach music-making technically?

“The whole grime scene came about because people were using Fruity Loops or that PlayStation program. I’ve interviewed Trevor Horn, Arthur Baker and Adrian Sherwood and they told me a lot of the tracks they made that I love the most were things they were just fucking around with. When Todd Terry was making some of those amazing tracks, he was dicking about and did them in half an hour. It makes me wonder if I think too much. Some of the best things are made when you switch off your thought processes and just do it, and most of the best things I’ve done came from mistakes.”

What new technologies have been transformative?

“I think right now Ableton Live has undoubtedly transformed music-making because it’s so fast to use and you can get your ideas down quickly. I always thought that if things aren’t a struggle, something’s gone wrong. Some of the tracks on System were re-edited or mixed 100 times, but I want to change all that. I’m quite interested in the new Teenage Engineering sampler, but everyone’s buying them so a lot of music will start sounding the same. That’s part of the reason I haven’t been using Ableton – I can hear when someone’s made something using it.”

We understand your new label will be completely physical – no social media or even an email contact?

“For me, there’s too much noise out there and I want to disconnect from that for a bit. Social media is my biggest fear. It’s about being in a room with thousands of other people who either hate or love what I do, but everyone’s completely coked out of their mind and talking about themselves. That’s how I feel in the bubble of social media. I’ve struggled with that on a social level too – I didn’t want to share private things with other people, but when it comes to putting records out I felt I had to use it. The majority of people don’t even know about most of the records I love, so the idea is to create a label that doesn’t exist online and you can’t contact me without sending an SAE. I’ll send a list of records coming out and people can send me a cheque or cash to buy them, which will probably be hard work but I just want to give it a shot.”

Do you feel social media is cynical and artists are just tapping into people’s emotions to sell product?

“It’s about creating the illusion of a relationship and keeping yourself in the public eye. I see artists I love and respect talking about taking the cat out or making a cup of tea; it’s fucking banal. For me, it should be purely about music and, I was going to say marketing. The mystery’s gone. I want to hold the people I respect on pedestals; not even think about them as human [laughs].”