The history of breaks in music production

We trace the influence of breaks in music-making from the birth of hip-hop through breakbeat hardcore, rave, jungle and DnB

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What is a breakbeat? Simply put, it’s a beat that’s found in a song’s drum break, a section in which other instruments fall silent to leave the drums and percussion playing on their own. The term ‘break’ refers to the notion that these drum parts are found during breaks in the music; gaps in the arrangement where the drums sound by themselves.

These drum breaks would typically be found in funk, soul, jazz and R&B recordings, most of which centred around vocal arrangements and varied instrumentation – however, many tracks would feature four- or eight-bar segments, often found in the transition between verse and chorus, in which the drums played a groove solo.

For enterprising hip-hop producers and DJs in the ’70s, the discovery of these breaks on vinyl records presented an opportunity to repurpose existing rhythms to their own musical ends. It was a way for young, cash-strapped musicians to work with great drummers without the need to source session musicians or pay studio fees. This simple act of musical resourcefulness changed the course of musical history.

Enter the B-boys

Though they’re now associated with dance music genres like jungle and drum & bass, the use of breakbeats was pioneered by those working in hip-hop, and breaks have remained a staple element of rap instrumentals over the decades. Although breaks are now mostly used as samples, they were first used in live performance by hip-hop DJs accompanying rappers and breakdancers.

Clive Campbell, aka DJ Kool Herc, is credited with pioneering this technique and laying the foundations for the genesis of hip-hop. While DJing at parties, Herc noticed the crowd would respond enthusiastically to breaks in the funk records he was playing. Rather than wait for the breaks in each song to appear, he began to use two turntables and a mixer to juggle between multiple breaks – as one reached the end, he would cue the second record’s break, transitioning seamlessly between the two, dubbing this technique “The Merry-Go-Round”.

The technique soon caught on, as figures like Grandmaster Flash and Afrika Bambaataa began to develop the approach while continuing to explore the musical possibilities that breakbeats opened up. In the early ’80s, hip-hop transitioned from a nascent subculture based around live DJing and MCing at Bronx block parties into a fully-fledged musical genre, recorded and produced in the studio.

It was in this era that the first commercially available samplers became popular, making it cheaper and easier for hip-hop producers to sample breakbeats for use in their tracks. Though the Computer Music Melodian, released in 1976, lays claim to being the first sampler on the market, and the Fairlight CMI, released in 1979, was the first to really take off, these instruments weren’t suited to working with breaks – the CMI only offered a single second of sample time, nowhere near long enough to fit in a four-bar breakbeat, and cost $18,000 to buy.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

This meant that in the early days of hip-hop, producers would have to record drummers in the studio recreating their favourite breaks – as heard on Sugarhill Gang’s 1979 classic Rapper’s Delight – or to record live beat-juggling from two turntables and a mixer straight to tape, an approach Grandmaster Flash took on The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel, a 1981 single featuring the legendary Apache break.

As the ’80s rolled on, portable, affordable samplers became available and the golden era of breaks-based production began. Producers were able to lift breaks directly from any record with relative ease, chopping them up and layering them over other musical elements in their tracks. Akai, the manufacturer responsible for some of the most iconic samplers, began releasing models in the mid-’80s.

Rackmount units like the S900 and S950 preceded the iconic MPC series, which began in 1988 with the MPC60. The MPC, with its 16 playable pads, made slicing, dicing and sequencing breakbeats quick and simple. Along with similarly influential instruments like the E-mu SP-1200, these samplers played a pivotal role in shaping the development of hip-hop beat-making and production.

Junglist massive

Inspired by the way hip-hop artists were working with breakbeats across the Atlantic, British and European producers began to incorporate the samples they were hearing in hip-hop – the Amen, Think and Apache breaks – with new sounds that had also emerged from American origins: namely, acid house and techno.

Genres like breakbeat hardcore were the first in which breaks were sped up to tempos of 150-170bpm and repurposed into the rhythmic context of dance music and rave, renouncing the straight 4/4 pulse that characterised house and techno in favour of rhythms based around breaks. This development paved the way for the birth of genres like jungle and drum & bass, which centred around complex, syncopated drum patterns pieced together from sampled and processed breakbeats.

The role black artists played in creating the roots of dance music is well known, but emphasis is often put on the early pioneers of house and techno. What can be overlooked is the way that hip-hop, dub and reggae artists directly inspired the roots of rave, jungle and countless other European-born sub-genres.

Speaking to Future Music back in 1993, The Prodigy’s Liam Howlett admitted that his road to inspiring rave’s commercial breakthrough was rooted in abortive attempts to create hip-hop. “I’d bought a Roland W-30 with which I was writing hip-hop stuff, but I’d had no success,” Howlett explains. “I moved over to house just as the rave scene was taking off. After watching N-Joi, Adamski and Guru Josh on stage I realised, ‘I can write this music myself with what I’ve already got’.”

Speaking to FM in ’96, Photek, a pioneer of jungle’s more expansive offshoot drum & bass, acknowledged similar inspiration. “To me, through hip-hop I wanted to know where the breaks came from, to know where samples came from, that sort of thing. Then you get onto jazz, it’s the most natural thing. Drum & bass came through the love of hip-hop beats, and I think that’s the same for everyone really. It’s such an obvious forerunner to drum & bass, the whole roughness, the rhythms, the breaks.”

Compilation albums like Ultimate Breaks and Beats made iconic breaks widely available for producers to sample, as jungle and drum & bass producer Krust explains: “Breaks back then, we had tons of them. We were scratch DJs and hip-hop DJs, so we had all the Ultimate Breaks and Beats records, we knew all the breaks and we knew all the records that had breaks on. That wasn’t really a problem for us. But if we had to get more, then we knew we’d go to secondhand shops in Bristol and in London. We’d just sit down and go through chopping up and sampling.”

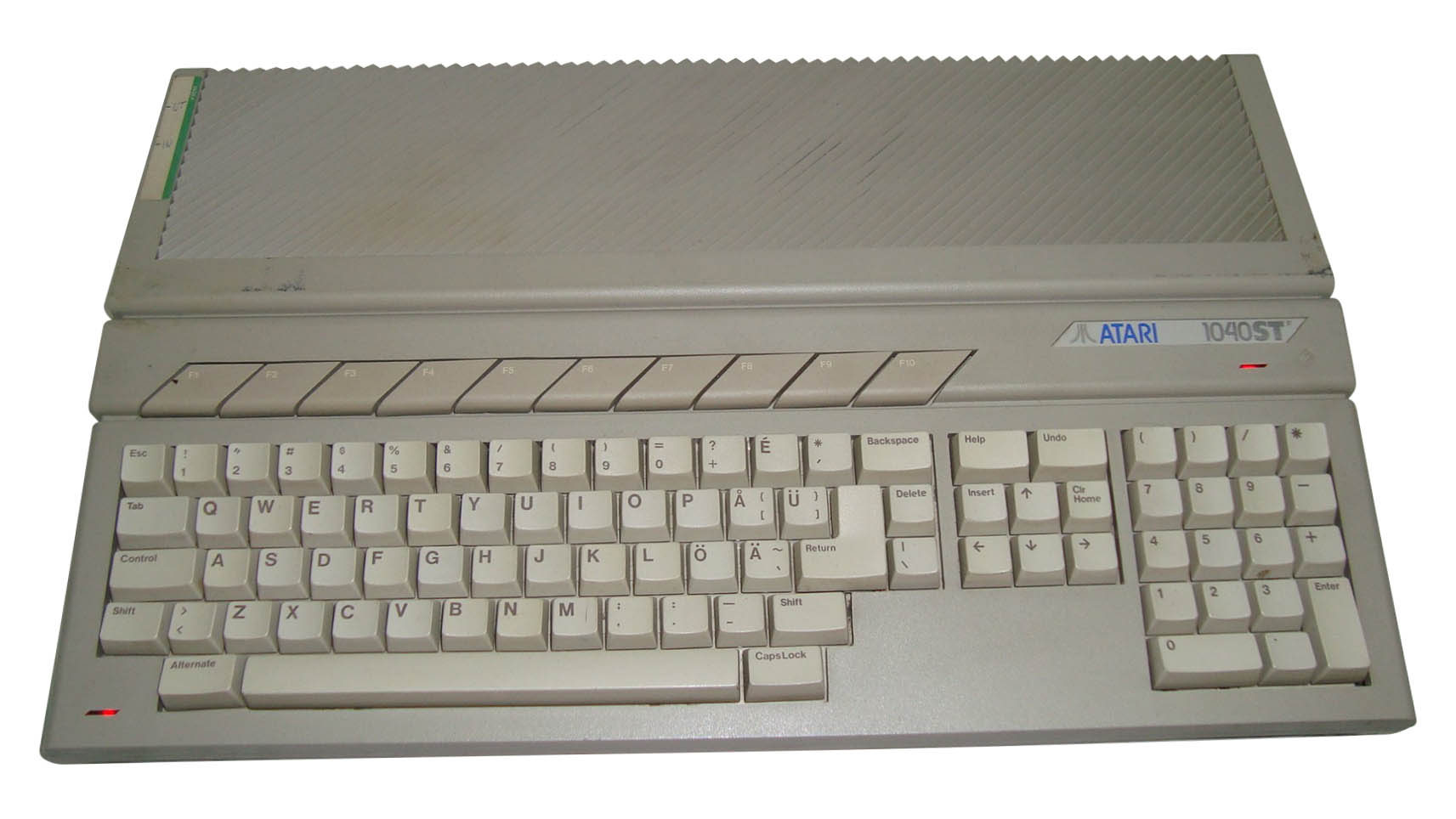

Fortunately for us, the Atari 1040ST had a MIDI connector on it. That changed the whole music industry pretty much overnight

During this time, producers working with breaks would more than likely be using a setup that consisted of a PC, such as the Atari ST or Amiga 500, running Cubase (or Pro 24, its predecessor), and a sampler. Machines like the Atari made music-making accessible to bedroom producers for the first time, as jungle producer Ray Keith says: “Fortunately for us, the Atari 1040ST had a MIDI connector on it. That changed the whole music industry pretty much overnight, because before that, if you were trying to make music, you would have to hire a studio. And they were really, really expensive. So you’d be hiring the studio, and that’d be per hour, and then also, you’d be hiring an engineer. Now back in the day that could cost you anything from £500 to a grand a day.”

Much like hip-hop’s beat juggling in the ’80s, the process of chopping and resequencing breaks was somewhat at odds with the traditional approach to recording a rhythm track. Speaking to FM in 1997, DnB pioneer Blame recalled the confused looks he’d get from engineers when trying to explain his approach: “I’ve been in studios and I want to chop this break up and they look at you as if they’re thinking, ‘What is this geezer on about? Taking hi-hats out of a breakbeat?’ And you’ve actually got to go step-by-step through it and then an hour later they’ll go ‘oh, I see what you are doing!’.”

Breaks would be sampled using samplers from manufacturers like Akai, E-mu, Roland and Casio, then sequenced using the Atari computer. This was a laborious process, far removed from the quickfire editing that’s possible using the modern DAW. “Everything was sampled from the record into the sampler, and then it would take my engineer at least 40 minutes to an hour to cut that break up into pieces, put it up on the keyboard, and then you’d be able to play each individual sound and then recreate that on your screen. That was the hardest part,” Ray Keith recalls.

“The more complicated the break, the more it would have to be cut up, because then you’d be able to loop it. So you needed to pick an engineer that understood science, and was spot on, because if the tune was baggy, then once you play it back and you sync it at 150 or 155, you would hear it drift out. It had to be on point.”

Blame, speaking in ’97, lamented the way this time-consuming process could derail the creative flow. “When I’ve got an idea in my head it’s just got to flow down straightaway,” he says. “There are so many times when I’m at home with a piece of paper and draw a lot of dots on it, like they did on those old music programmes. But I’ve got to do it because by the time I’ve loaded all the gear up it’s gone, but I can look at those scribbles and know exactly what I want.”

You’re just trying to create something different based on the original idea of the breaks

More often than not, breaks would be chopped up into snippets that would be triggered using a MIDI keyboard. The idea was to rearrange the drum pattern in new variations, which would be layered and pitched up and down or manipulated with effects processing. “You’d sample a whole break, then you copy the kick, you copy the hi-hats, you copy the snares, and maybe copy a couple of variations. And then you’d put them all on the keys, starting at C1 and then going up the keyboard, until you had recreated the whole break,” Krust explains.

“Then you’d set the tempo, and then essentially you’d recreate that same break, but at 165bpm. So when you put the break together, you just go into each part of it and tighten it up. Sometimes you pitch them up, sometimes you pitch them down. You’re just trying to create something different based on the original idea of the breaks.”

Them's the breaks

Jungle’s raw, gritty sound is beloved by its fans, but this largely wasn’t the result of an intentional style choice. Artists were mostly self-taught, and didn’t adhere to the established studio practices used by professional producers and mix engineers. “None of us went to music school or music college,” Krust tells us. “We never knew about ducking, mixing, phasing, EQs, all that stuff. We were going to free raves, we were hearing music, we were coming back. And we were just sort of chopping it up and figuring it out as we went along. So we just learnt best practices, things that would make it work.”

This helped shape the rough sound characterising many classic jungle and drum & bass productions. “Working on the Mackie desk, we were working in the red all the time,” Krust says. “It wasn’t that we were distorting it just for the sake of it, it just sounded better coming out of an analogue system, through the desk, because the Mackie distortion just sounded great.”

We were going to free raves, we were hearing music, we were coming back. And we were just sort of chopping it up and figuring it out as we went along

Not only did this experimental way of working inspire a distinct sound, but it led producers to become very protective over their techniques. In the early and mid-’90s, dance musicians were navigating their way through a rapidly advancing technological landscape. Discovering a fresh and distinctive way to process, sequence or rework your samples was often the thing that let a producer stand out from the crowd.

Speaking to FM in ’97, Rob Playford, who had just engineered Goldie’s huge breakout record Timeless, explained how tightlipped the scene tended to be. “There’s a lot of tricks of the trade which I can’t reveal! There’s something I came up with on Timeless with the beats. We say they ‘snake’. It sounds like the breakbeat just comes alive and writhes around in front of you – jittering about. There’s only three people who know how that’s done!”

Part of the reason behind the guarded nature of the scene in those days comes down to the limited pool of source samples many producers had to work with. Unlike today, where a new producer can simply put the words ‘drum solo’ into a search engine and find a seemingly endless list of recordings and videos, in the ’80s and ’90s many producers relied on the same pool of commercially available breaks collections or word-of-mouth recommendations.

Long time drum & bass and breakbeat producer Ed Solo recalls his introduction to one of the best-known breaks: “I remember I was in a session with Shy FX and his engineer, and they started talking about this thing called ‘Amen’. And I said to him, ‘Sorry, guys, what’s this Amen?’ and they’re like, ‘Oh, it’s that break’. Just from them saying that, I got it, literally like 90% of tunes in the jungle days had that Amen break in.

“I remember another engineer found a copy of the original Amen tune on 7-inch for me. That was the first time I ever heard the whole Amen track. I put on the record and it got to the right part, he started playing the drums and it’s brilliant. I then grabbed the record and wound it back to play it again. But where the needle was wasn’t quite right and it was a really old record, it messed up the record and I didn’t get a chance to sample it.”

Unique ways of processing and reworking breaks played a significant role in the way producers defined their own distinctive sound

With a multitude of artists making use of the same drum breaks, unique ways of processing and reworking them played a significant role in the way producers defined their own distinctive sound. These differing approaches even came down to how musicians sampled the records themselves, as Ed Solo explains. “With the Amen, the left and the right channels were different from each other. So certain people would sample the right-hand channel, which was more kind of compressed, so most people use that, like Ray Keith. Then people like Bukem would sample the left side, which was lighter and had more of the rides and the attacks of it and stuff.”

By the mid-’90s, jungle was a nationwide phenomenon, and had triggered the rise of drum & bass, along with a raft of subgenres that were built on breakbeats: breakcore, drill and bass, ragga and hardstep, among others. It would be a misnomer to suggest that every artist was using breakbeats in a similar manner.

Take big beat, for example, one of the most commercially successful genres in the mid-’90s, associated with the peak of popularity for bands such as The Prodigy, Chemical Brothers and Fatboy Slim. Unlike the more underground elements of drum & bass, where breakbeat manipulation was becoming increasingly more complex and detailed, many of big beat’s most notable tracks reverted back to an approach similar to that of early hip-hop, where drum parts were used as wholesale loops, beefed up with electronic drum machines.

In the hip-hop world, meanwhile, the chop-and-loop approach that early DJs took to working with drum breaks eventually came to be applied to full tracks. The rise of affordable samplers created the distinctive style of cut-and-paste beatmaking that defined much of ’90s hip-hop, where drum breaks were layered up with roughly chopped instrument stabs and vocal hooks, augmented and thickened up with extra samples and synth tones.

Speaking to FM in 2006, Arthur Baker, one of the forefathers of the approach, recalled, “when [those samplers] came about I was like, ‘let’s make rap records without the rap,’ so we made all these instrumental collages. Back in those days I was using the Emulator 1 and Emulator II, then all the Akai samplers like the S700, S900 then the S1000. That was all the gear you needed.”

Following that initial wave of sampler tech, in ’90s hip-hop, Akai’s MPC line reigned supreme. With its user-friendly approach, much-loved trigger pads and quantise settings, the MPC allowed hip-hop artists to not only slice and sequence beats and hooks, but play them live by ‘finger drumming’ the pads, bringing an extra layer of groove to the beat.

Going digital

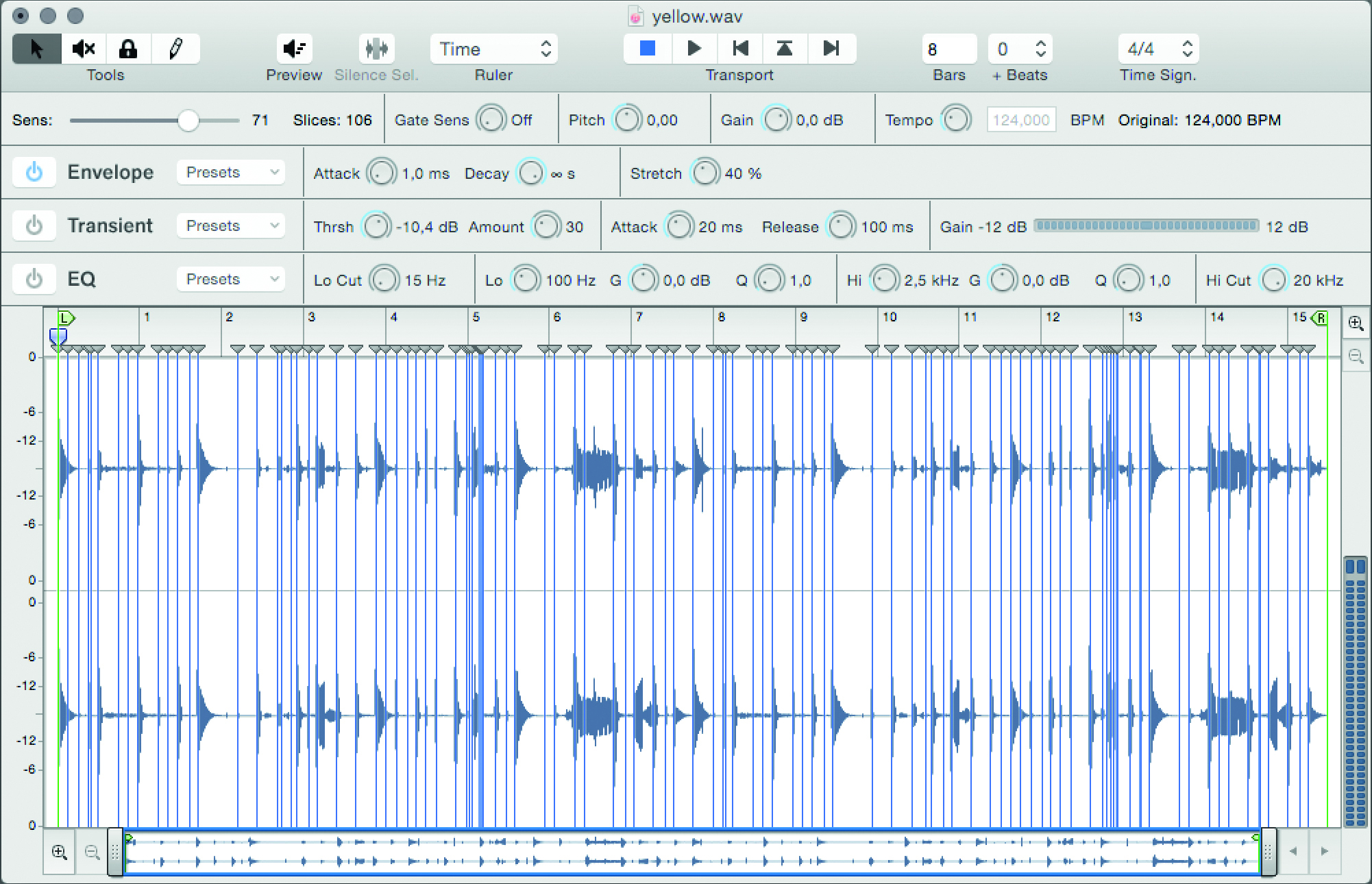

Throughout the ’90s, music technology was rapidly developing and PCs were becoming more sophisticated, along with the software they operated. Software tools like Propellerhead’s ReCycle, released in 1994, delivered an advanced level of functionality for those working with breaks, along with new DAWs like Pro Tools.

When Pro Tools happened, it’s like, oh my god, you’re kidding me. It was like we’d discovered a whole new world

“When Pro Tools came out, it was all digital,” Krust recalls. “Everything started on the one, you could start the track anywhere. It was really exciting to be able to start the track everywhere. Before that, we had to rewind everything back to the beginning, make sure it all synced up, then press play, and then you have to listen to the whole thing. When Pro Tools happened, it’s like, oh my god, you’re kidding me. It was like we’d discovered a whole new world.”

As the 2000s rolled around, technology began to reach a point that fundamentally changed the way breakbeats were used in electronic music. So much of what we define as distinctive ‘breaks’ production techniques involved working around limitations that no longer existed. Hardware samplers limited recording time in a way that wasn’t an issue with computers. Software like Ableton Live has brought advanced time-stretching to the masses, negating the need to carefully repitch or re-sequence drum parts to adjust their timing. The samplers in most DAWs, or modern hardware like Akai’s current MPCs, can slice a drum loop in seconds. What’s more, with the quality of modern sample instruments, getting your hands on a realistic sounding drum part can be as simple as creating one in your DAW.

For many producers looking to capture the sound and feel of breakbeat-centric music using modern gear, the process involves a certain amount of returning to supposedly outdated ways of working.

That way of doing it in the Akai and that way of programming it with MIDI, is very much a part of how you get your sound

Award-winning DnB duo Serial Killaz have a history in production that’s spanned numerous decades and technological eras. Tobie Scopes explains how technology has changed their approach. “When we made the switch [to digital technology], it was actually quite noticeable in our tunes. I’ve found myself going back to the older ways. There was just a vibe that was there from being able to cut breaks, do MIDI with breaks with the jungle sound, that way of doing it in the Akai and that way of programming it with MIDI, is very much a part of how you get your sound.”

As Krust says, modern approaches do more than change the sound of sampled drums, they change the workflow: “One thing that we couldn’t do is that you couldn’t leave a tune on the desk,” he explains. “Back in the day when using the Mackie setup, the Mackie, Atari and sampler, it forced you to finish what you’re working on. There was no coming back next week. You know, if you wanted to finish off making a couple more tunes that week, that had to get done.

“And so what the digital thing did was like, you don’t have to finish it. In a way, it was better because you accumulated lots of ideas but in another way, it made you lose that sense of urgency. I missed that a little bit. But, you know, I do like the convenience of today. Now it’s about having the best of both worlds, we’ve got a lot of analogue and a lot of digital. A lot of people now are figuring out how to get the best of the old world, but in the new world.”

It’s very hard to pull out a modern breakbeat and have something that sounds as authentic and as good as those classic breaks

As Tobie from Serial Killaz says, capturing that distinctive breakbeat sound is about more than just production techniques though. Much of the feel and sound is derived from the era of the sampled records themselves. “I find now it’s very hard to pull out a modern breakbeat and have something that sounds as authentic and as good as those classic breaks,” he explains.

“Those classics like the Think break and the Amen, you know. We’re big advocates of those original breaks, and just how good those drummers were. It’s like a lost era that just doesn’t seem to happen anymore. You know? We’re fans of how that influenced jungle, even to the extent that some of the tunes the breaks were taken from provided other samples that ended up in those jungle tunes as well. You ended up sampling the chords or the vocal or anything else too.”

Back once again

Dance music trends ebb and flow, and the importance of breakbeats has risen and fallen with them. The golden age of the breakbeat has passed; subgenres like breakbeat, big beat and breakstep have been left in the past, and although drum & bass and hip-hop are still going strong, the influence of breaks on either genre has waned.

In much of modern DnB, the raw style of drum sampling has given way to a highly refined approach, where producers finely tune layered combinations of samples and synthesis to make sure each drum hit has maximum dancefloor impact. In hip-hop, sampled drum grooves have largely been eclipsed by the spacious, drum machine-centred beats of trap and drill. While sampling is still a core element of hip-hop beatmaking, looped drum grooves tend to be seen as a ’90s throwback.

Over the past few years, a lot of people started to use breaks again, because it’s lost that human, organic element. People are bringing that back in again

That said, there’s been a definite resurgence in the use of breaks in electronic music in recent years. The likes of Paul Woolford’s Special Request project and Bicep’s crossover hit Glue have helped to drag rave-style break loops back out from dance music’s fringes into main rooms and festival tents. In drum & bass too, an increasing tendency to revive the ‘old ways’ has emerged, possibly as a reaction to the slick production values of some of the genre’s big hitters.

“Over the past few years, a lot of people started to use breaks again,” Ed Solo tells us. “I think because it’s lost that kind of human organic element. People are bringing that back in again now, which is a good thing. We’ve gone a little bit back to people using the whole break, where they might not be perfectly quantised. But they’ll put kicks and snares over the top. The Think break has made a big comeback, actually – lots of people seem to be using that. Whether they’ve tightened it up and then reprocessed it or not, I don’t know. Some people are just using the whole original thing, which kind of brings the funk back a little bit.”

Krust understands the appeal of reviving older approaches. “I think it’s valid. It’s just like anything, we go round in cycles, right? What’s in flavour tomorrow won’t be next week. But, you know, Warren Buffett said it the best: when everyone zigs, I zag. You’ve got to just figure out the best tools for the job and sometimes, it is the old-school way of chopping breaks, getting out ReCycle. Why? Well, no one’s using it. So then it’s a great idea. A lot of people now are going back to the E6400 and desks, you know why? Because not many people are using it. And you can’t beat that organic analogue sound.”

The problem is that most of these youngsters coming into it don’t know where the music came from

For others, like genre icon Ray Keith, production will always centre on breakbeat roots. “I still go out, I still look for records, I still look for breaks, I still get inspired by music that I listen to outside the box, because that’s how I was taught,” he tells us. “The problem is that most of these youngsters coming into it don’t know where the music came from. They don’t know who Bobby Byrd is, or Lynn Collins is. They don’t know the history of James Brown. And that’s quite sad. Because if you mentioned that to them, they’re like – ‘what? No, that’s this break.’ And it’s like, no – that came from Motown, or that came from rare groove, or that came from soul.”

Ray Keith's autobiography, Dark Soldier, is out now.

Krust's latest album, The Edge of Everything, is out now on Crosstown Rebels.

Ed Solo's latest track, Space, is out now. Visit Ed Solo's Patreon for exclusive dubs, tracks and more.

Serial Killaz' Top Cat remix, Friend in Need, is out now. Vital Elements from Serial Killaz teaches music production through Champion Soundz.

I'm the Managing Editor of Music Technology at MusicRadar and former Editor-in-Chief of Future Music, Computer Music and Electronic Musician. I've been messing around with music tech in various forms for over two decades. I've also spent the last 10 years forgetting how to play guitar. Find me in the chillout room at raves complaining that it's past my bedtime.