John Lennon: "Somebody let off a firecracker onstage and every one of us looked at each other, because each thought it was the other that had been shot. It was that bad.” – Why The Beatles retired from the stage

How death threats, disillusionment and the very real threat of onstage electrocution all fuelled The Fab Four’s decision to stop playing live…

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

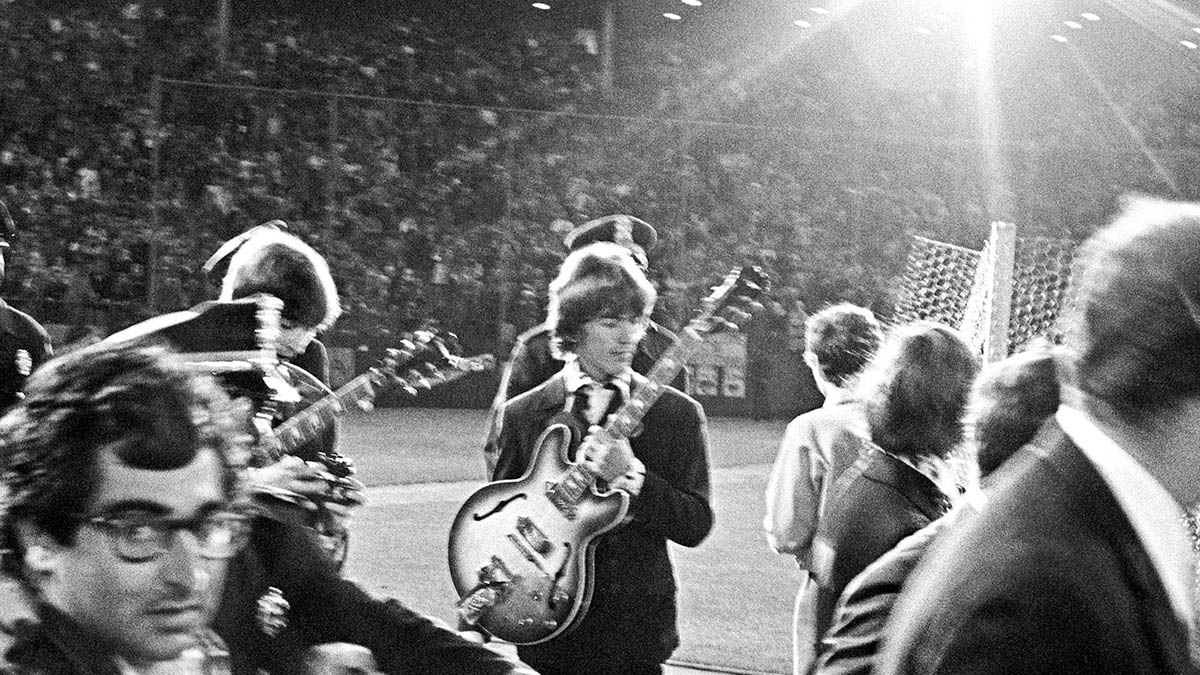

At 9:27pm on 29 August 1966, the four members of The Beatles walked on stage at Candlestick Park in San Francisco to play their last ever show in front of a paying audience. It was a cold, windy evening and fog shrouded the stadium, which was home to the San Francisco Giants. The Beatles were running late and the backstage area was rammed.

“The dressing room was chaos,” the show’s compère, disc jockey ‘Emperor’ Gene Nelson of KYA 1260AM, said in Keith Badman’s The Beatles Off The Record. "There were loads of people there. The press tried to get passes for their kids and the singer Joan Baez was in there. Any local celebrity, who was in town, was in the dressing room. They were having a party."

The show was the last of 18 concerts on a 13-date tour of North America, with the band playing two gigs on some dates. The Beatles recognised the significance of the Candlestick Park concert and took steps to capture the moment.

"Before one of the last numbers, we set up this camera on an amplifier," recalled George Harrison in The Beatles Off The Record, "Ringo came off the drums, and we stood with our backs to the audience and posed for a photograph, because we knew that was the last show."

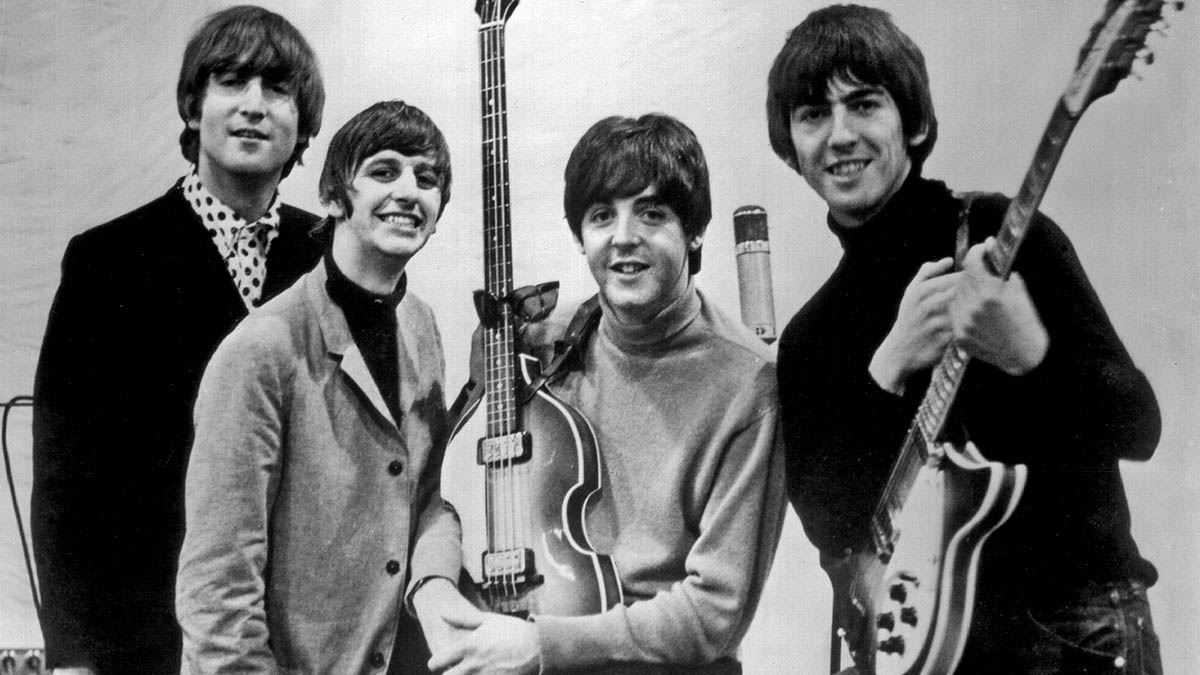

The decision to stop playing live was the culmination of a year in which their fame had taken a deeply malevolent turn. Protests, violence and death threats now impinged on their lives.

The problems began on 29 July 1966, when an interview with John Lennon by UK journalist Maureen Cleave was republished in US teen magazine Datebook. "Christianity will go," declared Lennon. "It will vanish and shrink… We're more popular than Jesus now; I don't know which will go first – rock 'n' roll or Christianity."

The comments provoked outrage among far right religious groups. Over 30 radio stations banned The Beatles from the airwaves and some stations in the Deep South staged mass burnings of Beatles records. The controversy spread to Mexico, Spain and South Africa, and the Vatican denounced Lennon’s comments.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Brian Epstein flew to New York and hastily arranged a press conference at the Astor Tower Hotel in Chicago. According to Steve Turner’s book, Beatles ‘66: The Revolutionary Year, Lennon broke down in tears in front of Epstein and the band’s press officer Tony Barrow, while preparing to meet the reporters.

“It had got dangerous,” recalled Paul McCartney in Ron Howard’s 2016 documentary Eight Days A Week – The Touring Years. “And we were threatened. We knew we weren't being blasphemous, we weren’t anti-Jesus. In fact, we all had pretty religious upbringings, really, but you do see John as sort of a broken man, ‘cause he realised, he had to apologise. It was gonna be the only thing that would stop this. He's longing to break out of it, and do a joke, but he knows he can’t.”

For The Beatles, it was the beginning of an increasingly volatile period. At the end of June, after shows in Munich, Essen and their old stomping ground Hamburg, The Beatles flew to Japan, where they played five nights at the Nippon Budokan in Tokyo, a venue normally reserved for martial arts. They received death threats from far right groups who felt the venue’s spiritual status had been violated.

But the troubles really started when they played two shows in the Philippines on 4 July 1966. After one of two shows at the Rizal Memorial football stadium in Manila, they unwittingly failed to attend a breakfast reception on 5 July hosted for them by the president’s wife, Imelda Marcos.

There were all these shots with the cameraman focusing on empty plates and up into the little kids' faces, all crying because the Beatles hadn’t turned up

“We put the TV on, and there was a horrific TV show of Madame Marcos screaming, ‘They’ve let me down!’” recalled Ringo Starr in the 1995 documentary project The Beatles Anthology. “There were all these shots with the cameraman focusing on empty plates and up into the little kids' faces, all crying because the Beatles hadn’t turned up.”

When road manager Mal Evans went down to the hotel reception, he found that all security and support from staff had been withdrawn, as had the police escort to whisk them to the airport. Epstein was forced to phone ahead and plead with the pilot of their KLM flight to delay take-off.

A process of intimidation, instigated by Marcos officials, hampered them all the way. Taxi drivers suddenly seemed to forget how to get to the airport.

When they did get there, all the escalators were turned off and The Beatles and Evans were jostled, punched and kicked. Once on board the plane, Paul McCartney recalled that “we were all kissing the seats”. After a stop-off in India, the Beatles returned to Heathrow on 8 July and spoke of their experience in an interview with ITN.

“We got pushed around from one corner of the lounge to another, you know,” said McCartney. “And so they started knocking over our road managers and things, and everyone was falling all over the place.”

Ringo later described their ordeal in Manila as “the most frightening thing that's ever happened to me”.

The events in the Philippines prompted The Beatles to privately question Brian Epstein’s management of their tours. When told that Epstein was booking a tour for 1967, Lennon and Harrison said that the 1966 one would be their last.

When asked by ITN what was next on the band’s schedule, George Harrison quipped: “We’re going to have a couple of weeks to recuperate before we go and get beaten up by the Americans.”

The 1966 US tour began with two shows in Chicago on 12 August. Ticket sales were noticeably down on the previous year. Sales for their return to Shea Stadium were down to 45,000, which was 10,000 less than on their 1964 tour. At Candlestick Park, only 25,000 tickets were sold for the 42,500 capacity stadium, leaving whole sections of seating empty.

The drop in ticket sales was partially attributed to the fallout from Lennon’s ‘We’re more popular than Jesus now’ comment. This was fresh in people’s minds when the band played two shows at the Mid-South Coliseum in Memphis on 19 August 1966.

The radio boycotts, record burning and protests were still taking place. Six members of the Klu Klux Klan picketed outside the venue, dressed in full robes. In the middle of playing If I Needed Someone, an incident occurred that would help galvanise their decision to stop touring.

“There had been threats to shoot us, the Klan were burning Beatle records outside and a lot of the crew-cut kids were joining in with them,” recalled John Lennon in 1974. “Somebody let off a firecracker onstage and every one of us – I think it’s on film – looked at each other, because each thought it was the other that had been shot. It was that bad.”

The tour was riddled with other mishaps. At Busch Memorial Stadium in St Louis on 21 August, heavy rain resulted in the band playing beneath a makeshift corrugated iron shelter.

“It felt like the worst little gig we’d ever played at even before we’d started as a band,” said Paul McCartney in the 1995 documentary series The Beatles Anthology. “We were having to worry about the rain getting in the amps and this took us right back to the Cavern days – it was worse than those early days…

“After the gig I remember us getting in a big, empty steel-lined wagon, like a removal van… We were sliding around trying to hold on to something, and at that moment everyone said, ‘Oh, this bloody touring lark – I’ve had it up to here, man’."

Until that moment, McCartney had been the one band member urging the others to keep playing live. "I’d been trying to say, ‘Ah, touring’s good and it keeps us sharp. We need touring, and musicians need to play. Keep music live’. I had held on to that attitude when there were doubts, but finally I agreed with them."

There was another reason to stop touring. The PA systems at venues such as Candlestick Park were little more than speaker address systems for announcing scores to the crowds attending baseball games. They were shrill, trebly and woefully inadequate for bands.

Another factor was that The Beatles were increasingly unable to emulate the recordings they created in the studio. By the 1966 US tour, Paperback Writer was the only song from their latest album Revolver to make it into the set. Much of the set consisted of dated 12-bar covers such as Rock And Roll Music and Long Tall Sally, that they had been playing since the Cavern days.

As The Beatles walked on stage on 29 August 1966, only Ringo had lingering doubts about stopping touring. “There was a big talk at Candlestick Park that this had to end,” he recalled. “John wanted to give up more than the others. He felt that he’d had enough. I never felt 100 per cent certain until we got back to London.”

Rock and Roll Music

She’s a Woman

If I Needed Someone

Day Tripper

Baby's in Black

I Feel Fine

Yesterday

I Wanna Be Your Man

Nowhere Man

Paperback Writer

Long Tall Sally

After the show, the Beatles were rushed to the airport in an armoured car. They flew from San Francisco to Los Angeles, arriving at 12:50 am. At one point during the flight, Harrison was heard to say: “That’s it, then. I’m not a Beatle anymore.”

Harrison had been the first to tire of Beatlemania. In a quote from Martin Scorsese’s 2011 documentary George Harrison: Living In The Material World, George expanded on the group’s decision.

“We’d been through every race riot, and every city we went to there was some kind of a jam going on, and police control, and people threatening to do this and that ... and [us] being confined to a little room or a plane or a car. We all had each other to dilute the stress, and the sense of humour was very important ... But there was a point where enough was enough.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.