Producer Masterclass - Sub Focus: “Working with VSTs seemed quite natural for me, but for a lot of hardware producers, it was a difficult transition”

Nick Douwma shows us the tech that’s helped make him one of the UK’s most respected drum ‘n’ bass producers

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

MTS 2020: We met up with London-based drum ‘n’ bass producer, Sub Focus - aka Nick Douwma - just before it all kicked off. The virus stories were already making headlines at this point, so we jokingly shook hands with our elbows and tried not to cough over each other during the interview.

None of us knew how strange things were going to get, but it was obvious which way this ill wind was blowing. Just before we sat down for the interview, Douwma received a call from his live tech. A well-known DJ equipment manufacturer was due to demo some new equipment and wanted to know if Douwma had recently been to Asia. If he had, the demo was cancelled.

We had a brief discussion about live work. Would it be affected? Neither of us could imagine that a whole summer’s live shows and festivals would disappear.

It all seems so long ago, now.

It’s safe to say that Sub Focus is currently one of the UK’s leading dance brands, boasting a string of top notch singles - like 2019’s silver selling single, Desire - and a remix CV that includes The Prodigy, Bring Me The Horizon and Major Lazer/Nick Minaj.

Understandably, that success has seen a major change in his studio setup. Douwma is based in a large north London office complex that’s also home to fellow producers, Culture Shock and Dimension.

“The last time you interviewed me, I was working out of my bedroom,” he laughs. “But the great thing about that was having my flat mates on hand for listening sessions. They would offer advice on early mixes. ‘Maybe you should do an edit there. Keep that bit shorter.’ Constructive criticism is an important part of the musical process. You need another pair of ears that you can trust, otherwise you’re in danger of getting too caught up in your own sound.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Don’t get me wrong, you need to be single-minded and believe in what you’re doing, but also be open to ideas. It’s nice having Dimension and Culture Shock just down the corridor. And I’ve been mates with Chase & Status for years. When you play a track to someone whose opinion you respect, it forces you to be honest about that track. Does it really work?”

Douwma has been working on some house-flavoured tunes for possible release sometime this year, but, as you’d imagine, it’s drum ‘n’ bass that takes up most of his time and his most recent project has been a collaborative album with fellow DnB big cheese, Wilkinson.

Rumour has it that you started out as a rock kid, listening to Nirvana and early-’90s grunge. How did you end up making drum ‘n’ bass?

“Yeah, I started out in a band when I was at school in London, playing bass. But I was quite into computers and I’d managed to get my hands on an old Acorn with a printer port sampler. It came with some very rudimentary music-making software where you had to arrange samples using classical notation - a ridiculous setup for making dance music looking back on it! This was around the time when bands like The Prodigy and Chemical Brothers were beginning to mix rock and dance music, which was then a natural segue into electronic music.

“Perhaps the real drum ‘n’ bass catalyst, though, was buying the first Logical Progression CD around 1996, put together by LTJ Bukem.”

Ah… dolphin jungle?

“Yeah, I heard someone use that term when I was in Black Market Records at the time, but I had no idea what they meant. All I knew was that this atmospheric sound - Bukem, Photek and Goldie - really caught my imagination. Yes, it was electronic music, but it also had so much emotion to it.

“From there, I started investigating some of the techier stuff like Ed Rush and Optical, Bad Company. And the next step was making my own tunes.”

I’d managed to get my hands on an old Acorn with a printer port sampler. It came with some very rudimentary music-making software where you had to arrange samples using classical notation - a ridiculous setup for making dance music looking back on it!

Made on the Acorn?

“I’d moved on to a newer PC around 2000 and I started using Cubase. Looking back, I feel really lucky that I was getting into production at that time… the early to mid-noughties was when you were suddenly able to make whole tracks inside the computer and the quality of software instruments was getting much better.

“When I started releasing music a few years later, I got to know some of the producers I looked up to, and they were still working with hardware setups. Big Mackie desks, outboard samplers, synths and effects. Because things were changing so quickly, I felt like I had a bit of an advantage. The whole idea of working inside the computer with VSTs seemed quite natural for me, but for a lot of hardware producers, it was a difficult transition phase.”

And there were quite a lot of arguments about whether or not plugins sounded ‘as good as’ hardware.

“Exactly. But the sound quality was constantly improving and, of course, working with software was so much quicker and easier. I guess that move from being very hands-on when you’re doing a mix to automating everything inside the box was quite a profound change. It took a while for some people to make that psychological leap.”

That looks like Ableton Live on the computer screen… no more Cubase?

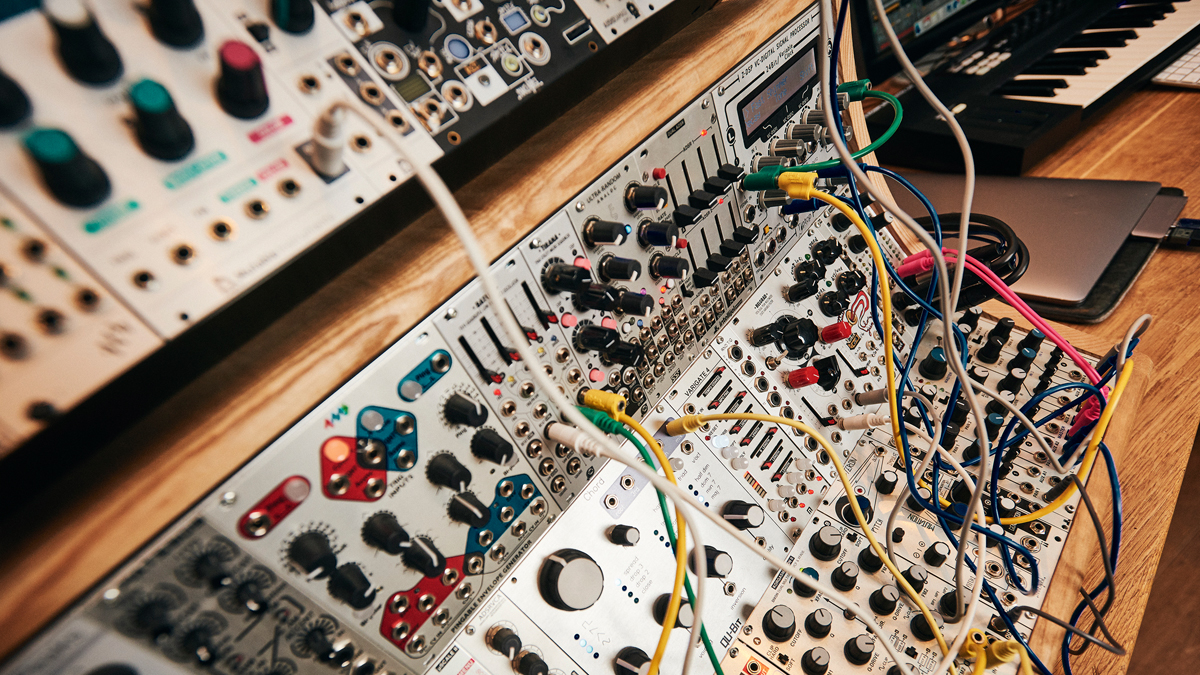

“I started using Ableton for my live shows back in 2010, so it kind of made sense to make the move in the studio. Initially, I was attracted to the workflow and the lack of hardware dongle - handy when you’re producing on the road. Preset management is also super-easy; I make folders of my synth presets, vocal chains and FX chains for quick recall. I also use a lot of the Max for Live plugins, like CV Tools, for controlling my modular synth.

“Another feature I use a lot is moving whole groups of audio between projects. Let’s say I’ve got a drum mix that I really like on a particular song. I can take that and put it on a new song, which gives me a nice starting point to work from. A drum reference. When you’re starting a tune from scratch, it can sometimes take a while to get the best EQ balance because your ears can quickly get used to a sound that is slightly off. If I introduce elements which already have a good tonal balance, it gives me a head start. It’s great practice to always reference other people’s music, too. I frequently have a mix reference group of tracks within my projects.”

Before we get onto the soft synths, I guess we are duty-bound to talk about the latest addition to your collection, a hardware Roland D-50. [It was delivered by courier and arrived in the middle of the interview. Douwma immediately plumbed it into the studio and got to work, tinkering around with the presets.]

“I’ve been trying to keep a balance between digital and analogue in my setup. I’ve been in some studios where they’ve got a fantastic selection of vintage monosynths, but I prefer to have a bit more of a range of tonal characters.

“The music that really first drew me into drum ‘n’ bass was Goldie, LTJ Bukem… I love those pad sounds. Digital pads can be very different to anything you’ll find on an analogue machine. Much thinner and shinier. Analogue pads sound fantastic, but they can also take up a lot of room in the mix with loads of low-mid. I like the idea of having lots of sounds from different eras at my disposal, and I love researching how different styles of music were made and how to recreate them.”

The early drum ‘n’ bass/jungle sound was quite digital.

“Yep, samplers and digital keyboards. People might include the 808, but the only reason the 808 became so important to the overall sound was because somebody sampled it, and that allowed producers to pitch it up and down. On the original 808, the kick drum has a set pitch. It’s quite funny, really. So many genres were influenced by that kick drum – trap, jungle, drum ‘n’ bass – but it was the sampling technology that made the kick so useful.”

Where do your drums come from? Samples you’ve collected over the years?

“Mostly. Although I have been starting to get into drum synthesis lately. When I make new drums, I record them as blocks of audio, so I have banks of hi-hat grooves, kicks and snares and breakbeats at my disposal. My drum hits are ones I’ve layered up and processed over the years, and I have reliable favourites that get re-layered and reused in various ways.

“In other genres, you can sometimes let things be a bit looser, timing-wise, but with drum ‘n’ bass, the timing of the hits needs to be bang-on. The drums I’m working with are usually fast and busy with a lot of layers, so I don’t tend to move away from the grid except on some 16th hits - ghost snares or shakers with swung 16ths.

“I’ll either create the swing manually by moving stuff off grid or use swing presets in Ableton. This only works in MIDI or rendered chunks of audio though. It can be tricky to get this right and make sure the swing on all channels is lining up.

“The track I’m working on in the video, Solar System, is more of a marchy groove, so there are less swung elements and more patterns on eighth-notes.

“I guess the thing about drums - and the bass, as well - is that it all depends on the song. I’ve found that, with experience, you kind of get a feel for what sounds right. Along with a few general rules that you need to be aware of.

“For instance, in drum ‘n’ bass, most of the bottom end comes from the bassline, so you keep the kicks a little bit higher up the spectrum. With house, it’s the other way around. The kick tends to take up more of the bottom end, so you need to cut more out of the bassline.

“I often use the spectrum analyser in WaveLab as a secondary visual reference to see if the various elements are hitting in the right place. I’m especially looking at sub level, the level of drum hits and overall brightness, as it’s often hard to read on speakers.

“At the bottom end, you also have to think about what key you’re working in and whether there are certain sub notes to avoid. A lot of drum ‘n’ bass songs are in F, but more producers are experimenting with lower keys now, like D, and this can give a nice weighty character to your bassline.

Benny L’s Vanta Black is a great example of this. The low C is nearly inaudible on most systems, so a C# is normally as low as I’d go, but there are a few hip-hop producers who have started working deep into that semi-inaudible range of sub. The results are fascinating, but might not translate to a club very well.

“Playing with tuning on sounds can be really interesting and is often overlooked. Some producers - like Gesaffelstein - really pay attention to the tuning. And it gives his tracks a distinctive sound. Basically, he’s not really pitched at 440Hz. All the synths are slightly out of tune and the whole thing floats around a bit like old analogue synths.”

Sorry, we got side-tracked, there. We were supposed to be asking you about soft synths...

“The main ones I use at the moment are Massive, Massive X, Nexus, Omnisphere, Serum and Sylenth1. Most of my bass sounds are made in wavetable synths like Massive or Serum. Wavetables tend to have a bit more texture and crunchiness in the top end and that’s great for mid-range bass.

“Often, I make my own synth sounds from scratch, but I also like to edit other people’s presets as this can be a great way to learn, especially on a new synth. There are some amazing presets that can be downloaded from sites like Splice or Cymatics.

I remember going into the studio with Pendulum way back in about 2005 and being blown away by how far ahead they were in terms of synths and synth-programming.

“I remember going into the studio with Pendulum way back in about 2005 and being blown away by how far ahead they were in terms of synths and synth-programming. I was still mainly working with samplers. So, I started teaching myself more about synth programming and tried to learn how to recreate different sounds. Sampling is great for a lot of things and it’s played a huge part in the development of drum ‘n’ bass, but when it comes to basslines, you need more control and freedom to modulate. Synthesis is key.

“I like quite a bit of movement in my basslines. One technique I often use is to put the same LFO on loads of different things like the filter, wavetable position, FM and EQ. Using the Max for Live Shaper and LFO plugins within Ableton, you can effectively LFO any parameter on any plugin. The sample & hold setting on this is a great way to introduce random values into your sounds, much as you would with a modular setup. I’ve even added them to reverb tails.”

Would it be fair to say that you like a big reverb?

“Absolutely, although it can be harder to mix tunes with loads of reverb. I love all the Valhalla reverb plugins. In my early days of producing, I remember liking the Neptunes sound, which was very tight with hardly any reverb. But it feels like the trend has moved the other way now, with lots of people using bigger verbs.

“Obviously, bigger reverbs do make things harder when it comes to mixdown because they can take up more space. That’s why I do a lot of rendering of audio. You can see how long the reverb tails are and make use of fades if you’re getting any clashes. Also, sidechaining and using plugins like the LFO tool can really help to clear out space for these. There’s often a lengthy process of simplification and taking away things when you’re trying to engineer a dance track.”

“That’s something I find myself doing in other areas, too. Taking stuff away. When I’m first programming the chords for a song, I’ll stick the root, third and fifth in there, then start the trial and error process of trying to work out whether they need some jazzy extensions. I also move certain notes around the octaves. Generally, a chord seems to get its feel from the top notes. But then I start taking notes out. Trying to find the notes that really matter and the ones that aren’t really adding anything.

“Complex chords - especially with analogue pad sounds - take up a lot of space in a mix. As long as you’re not damaging the song, reclaiming a bit of that valuable space is no bad thing.”

Sub Focus and Wilkinson’s new album, Portals, is out now.

This Producer Masterclass originally appeared in Computer Music 283 (July 2020)

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.