Johnny Marr: “I had an approach to the guitar that I knew was going to take some thinking about. A lot of it was about discarding the stuff I didn’t need”

We visit the ex-Smiths man at his studio

Spearheaded on guitar by Johnny Marr, The Smiths’ unique output of music from 1982 guaranteed them the solid title of ‘timeless institution’, even after their split in 1987. And with every decade since, their influence and futureproof back catalogue has continued to inform generations of aspiring musicians.

Although Johnny is perhaps best known for the five years he spent with The Smiths, that time represents just a fraction of his life in music, after leaving the band more than 30 years ago at the age of 23.

Always in demand, his prolific nature and restlessly creative disposition has seen him collaborate with an array of artists over the years including Bryan Ferry, Beck, Talking Heads, The Pretenders, Hans Zimmer and Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds, in addition to longer term projects that he embarked on with The The, Electronic, Johnny Marr and the Healers, Modest Mouse and The Cribs.

I wanted to make a modern rock record. I had an instinct about what that would be, but I didn’t analyse it

Johnny’s latest solo album, Call The Comet, comes after an intense period of reflection, which saw him delving deep into the past with his autobiography Set The Boy Free. And now, with his mind firmly back in the present, Guitarist dropped by to find out more about his new work.

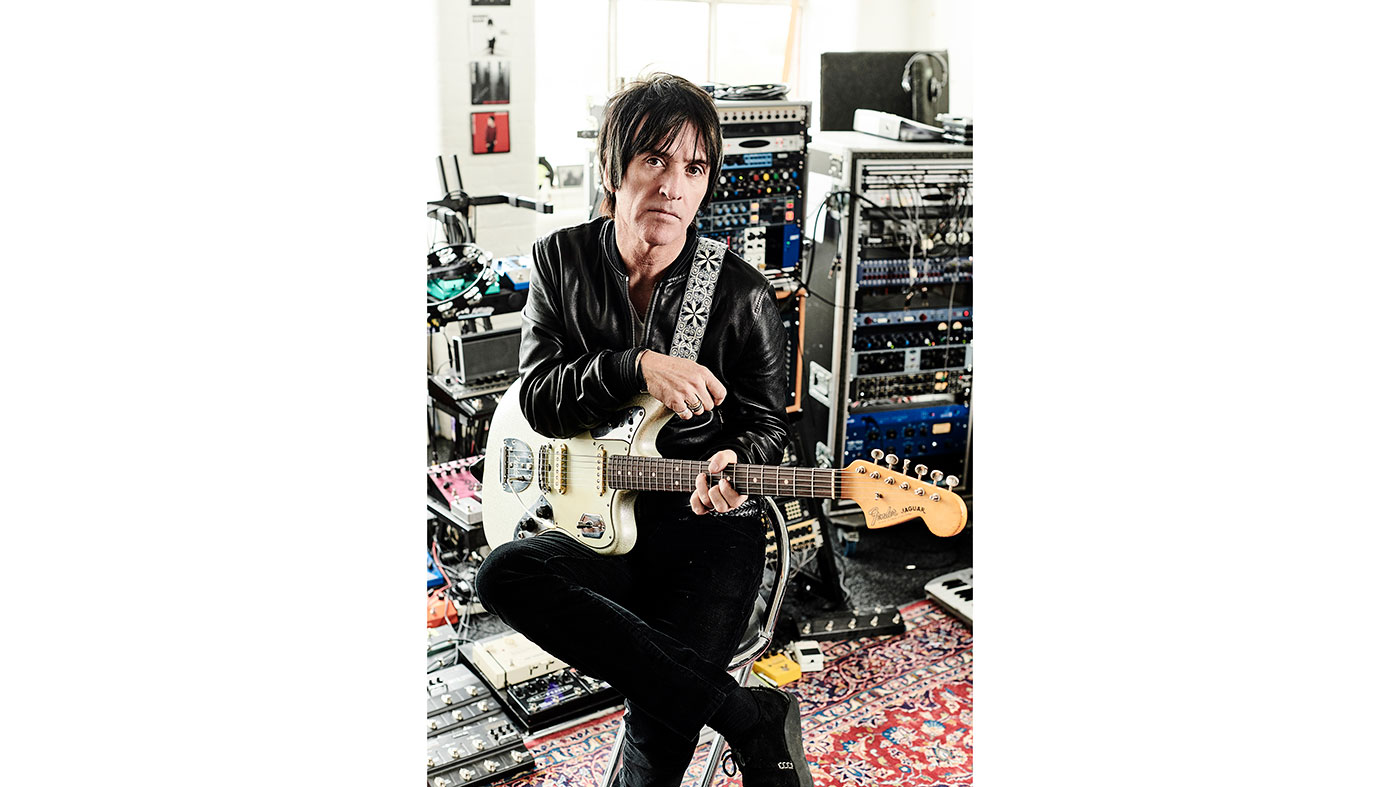

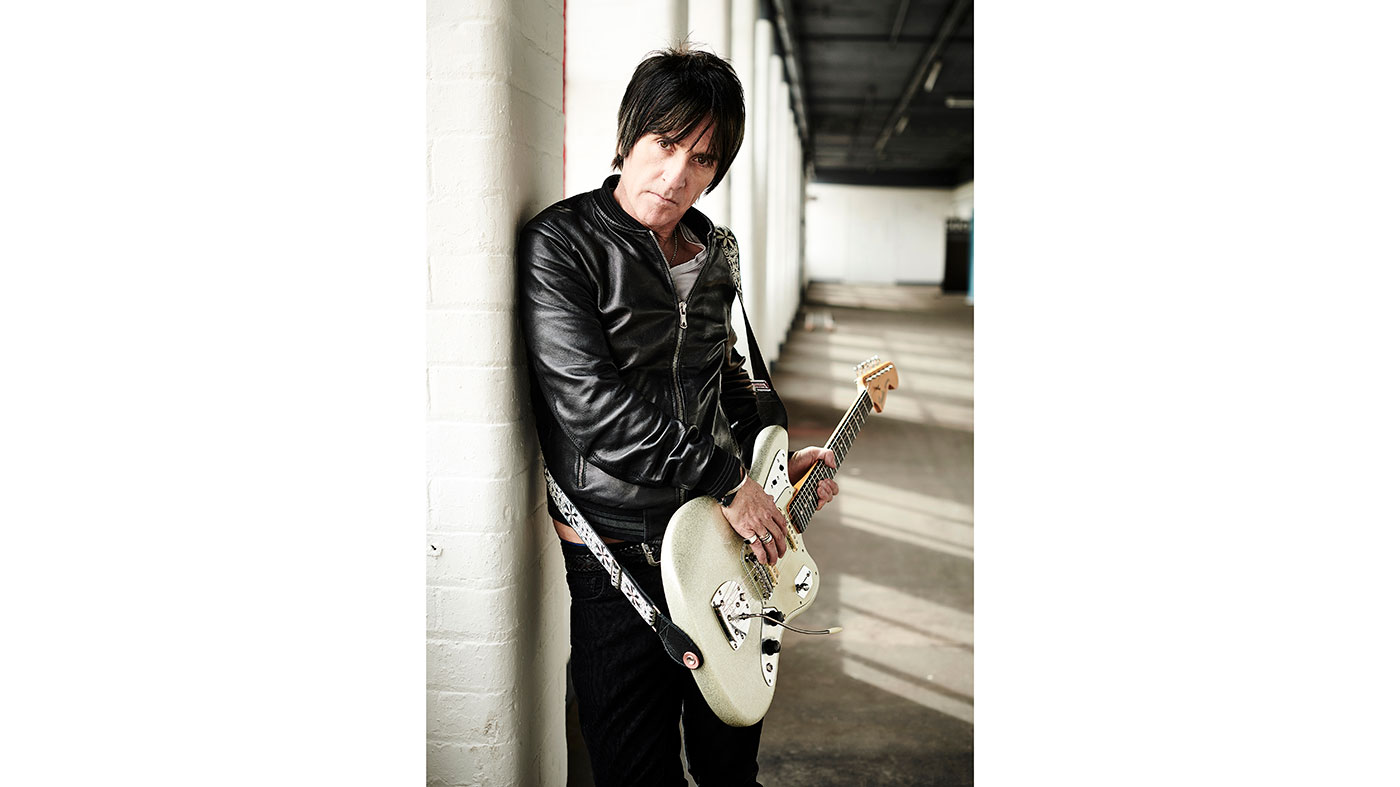

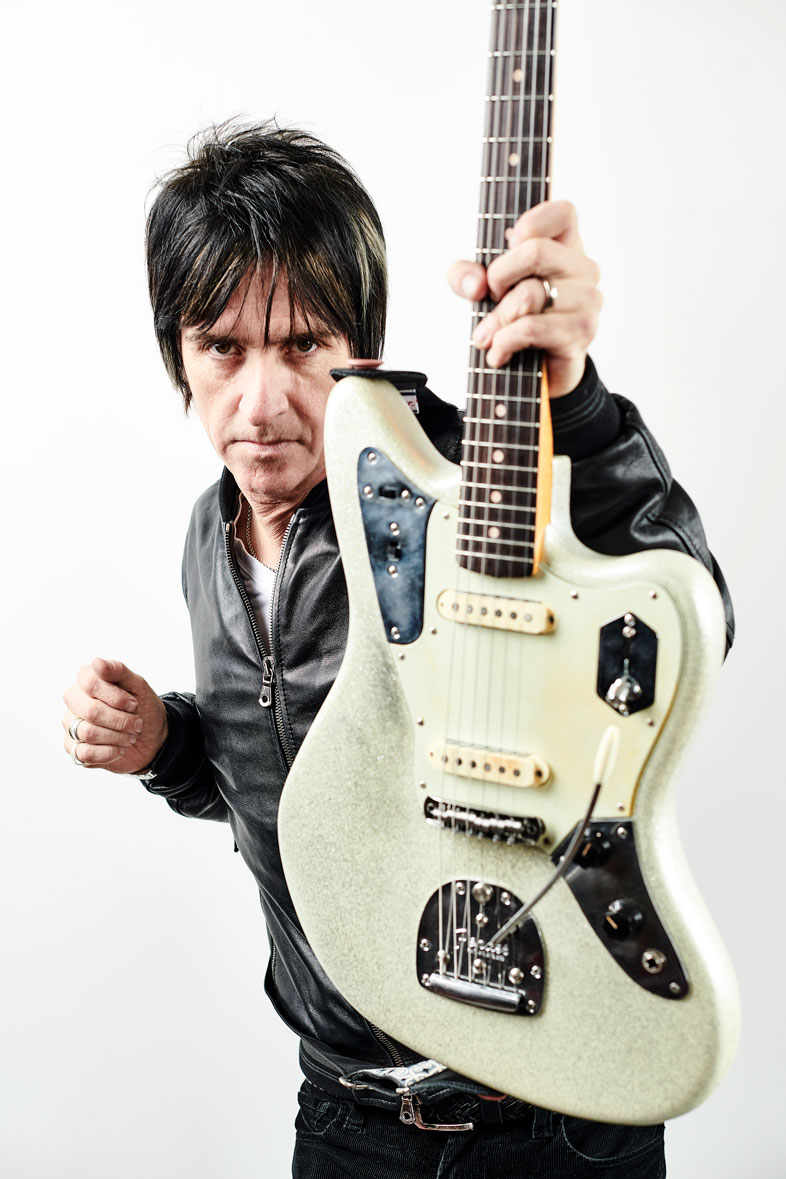

We arrive at his imposing red-brick Victorian factory building in Manchester and take the lift to the top floor - the location of his private studio space. After a warm welcome and a quick brew, we take a close look at some of the wonderful guitars in Johnny’s collection and make ourselves comfortable in the control room among the various instruments, amps, pedals and gizmos lying around in the aftermath of the album’s recording (perfect timing for a photoshoot!).

Congratulations on your new album, Call The Comet. How are you feeling now that it’s finished?

“Thanks very much. I’m really proud of it. It’s exciting. To be honest with you, I don’t really talk to people a lot about it. I’m still feeling a little bit like I’m rubbing my eyes coming out of the studio...”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

What was the inspiration behind it?

“I wanted to make a modern rock record. I had an instinct about what that would be, but I didn’t analyse or conceptualise it - I just walked into this place with one song written, which was Spiral Cities, and I just fell into trying to find this feeling of contemporary rock music. That’s one of the great things about having a life in music - I’ve learned that I can follow a feeling. A couple of other times in my career - Meat Is Murder was another time - I was following a feeling. I was following a different idea on Call The Comet.

“Sometimes I follow a concept - like putting the solo band together, that was more ideas about the kind of group I wanted to be in and the kind of songs I wanted to write. I had a lot of time to think about putting a solo band together when I was with The Cribs and Modest Mouse. I collected titles and developed a certain kind of idea about what I wanted to sing about.”

Rumble

What was the feeling behind the first single from the album, The Tracers?

“It’s inspired by Tyrannosaurus Rex. The feeling, when I got The Tracers together, was all about this rumbling in the drums and bass, and this idea that it was night time outside, the moon was out and there was a sense of portent - that kind of excitement you get when you’re a kid and you stay up too late and there’s a sort of mystery in the air and potential danger. That, to me, is one of the things that rock music does very well - or rock music as I’ve always thought of it. I went into this record being drawn to that feeling without even being aware of it, until I wrote The Tracers.”

Did it feel good to get back to making music and playing guitar after concentrating on your autobiography, Set The Boy Free?

My only direction was to follow a feeling, cross my fingers and hope for the best

“I spent a year writing the book and I found the promotion of it quite draining to be honest. I think, because I’d written the book, I had, literally, filled up all the pages, so everything was blank to me. Ordinarily that might be scary, but because making records and being in a band is what I do, I just had to get on with it. My only direction was to follow a feeling, cross my fingers and hope for the best. I was in the process of escaping into this big factory and into my new record and hopefully coming out the other end having gone through a whole mood, and using rock music to do it.

“Because the book was directly about the events that had happened in my life and was quite big in the mainstream, I found myself in a lot of mainstream media, and that’s quite intrusive, I think. I wanted the book to get the attention, but it definitely took it out of me. So, I was very eager to get in and play music, almost as a kind of refuge.

“There’s no doubt about it - making the record was an escape, and most of the themes of the record are about escape through alternative thinking. Whether that’s being a musician, or living in an alternative society, or being a character in the song Rise, or escaping with The Tracers, or escaping into Spiral Cities… ‘Fall in all in detournement, Follow illumination’ [Spiral Cities song lyrics] - that’s very much about going to a place. The lyrics for New Dominions are also concerned with escaping to a different environment.”

Are you feeling more grounded having gone through that process?

“Yeah, there’s no escaping the way society effects people - the difficulties, the hardships, the frustrations and just a weird feeling in the air. To deal with that, I kind of took full advantage of the fact that I’d been a musician since I was a kid and decided to honour the fact that being a musician gives me a means of escape.

“When you’ve been doing it a long time - particularly if it’s your livelihood - you can sometimes overlook just how much of an escape creativity and being an artist is.”

Alternative reality

Does music often feel more real to you than what other people might call ‘real life’?

“That was entirely the conclusion I came to as a child, but it expressed emotional truths that didn’t necessarily have to be expressed through language. I think the abstract nature of sound and music is the most effective means of communication. For example, if you make some really insane discordant, disorientating sound on a drill through reverb - as an industrial musician would - that’s going to convey the horror of potential doom probably better than any language!

I think the abstract nature of sound and music is the most effective means of communication

“I bought into the abstract nature of music being more descriptive and better at evoking emotions when I was about seven years old during Irish house parties at the house I lived in with my family - usually these very dramatic and sad tunes. That would then come out in stuff that I would write.”

As a kid, when you heard music were you listening out for the guitar?

“Always, yeah! That’s how I started out - just always looking out for guitar sounds, really. I identified to myself that the guitar was my main interest at a really young age. The grown-ups used to talk about me and my guitar, so it was reinforced - that was my thing. My parents were probably amazed by it, and also they really liked that idea because they loved music. Even when I was a teenager and I was playing really loud in my room and everything was all about the guitar!”

You threw yourself into it early. What was it like gigging with a band like Sister Ray at such a young age?

“I kind of saw it as clocking on to an apprenticeship, really. It was scary being in Sister Ray for that time. They sounded like Hawkwind and The Stooges and they took really bad drugs - speed and acid, but particularly barbiturates and all of that business. But I was so young - 14 - that I felt like if I were to do any more than five gigs with them then it was going to start to be a freak show.

“I remember being brought into Chris Sievey’s [of The Freshies] flat by this older guy and paraded about, as Chris was told, ‘You should get this kid in your band, ’cause he’s a shit-hot guitar player’. Chris looked at him, then looked at me and said, ‘Yeah, but he’s a kid?’ and I was standing there going, ‘Yeah, this is kind of ridiculous. I’d much rather be with my mates at the moment’. Also, I also knew that I had loads to learn. I knew what kind of standard I wanted to get to.”

Finding your feet

What was the focus behind concentrating on your technique?

“I was just so into using the guitar as a machine to make a great 45. I never forgot that. It was always in the service of not only a song, but also of making a record. I discarded loads of shreddy stuff because it wasn’t interesting to me and still isn’t. I would listen to records of that stuff and think, ‘This is rubbish - I’d rather be listening to The Temptations.’

I was just so into using the guitar as a machine to make a great 45. I never forgot that

“Luckily, I’d followed Rory Gallagher around and had seen Thin Lizzy so many times that I knew what really great blues rock and impressive, flash guitar playing was all about. That twin-guitar thing was really flash and was a great sound, and it did the teenage boy thing, but it’s not pointless, silly shredding that doesn’t sound anything like music.

“I wasn’t a snob about it, but as a teenager I had this idea of an approach to the guitar that I knew was going to take some thinking about. A lot of it was about discarding the stuff that I didn’t need. Right from the off on a record I always thought the guitar should make its presence known in the first three seconds.”

Was it as much about the production of rock music you listened to that informed your technique?

“I think growing up and being smitten by glam rock as an 11-year-old guitar player, and hearing all those great arrangements - whether it was Mick Ronson, Mick Ralphs, Chris Spedding, and the guys in The Sweet - all those guys who were making these great 3-and-a-half-minute guitar records. I never dropped that. The impression those glam records made on me and that excitement never, ever went away and is still with me now.

“I think the song Bug off the new record has got a bit of that in it. It deliberately doesn’t have a solo in it and it comes back to the intro riff and it’s a chant. I feel like I’ve made a guitar record - it’s a record that happens to be made by guitars, but it’s not about necessarily about the guitarist.”

Considering Hendrix and all the past masters, it almost seems pointless to try and make a statement based on technique alone…

“I always thought being an authentic musician was to aspire to or develop your own unique and original style, whether it was fancy and impressive or not. For me, when it comes to technique and expression, it’s all there in John McLaughlin, in My Goal’s Beyond (the first acoustic record he made), because the technique facilitates the music. He’s trying to say something fast, not just for the sake of it, but for the feel of it - and then it’s completely valid.”

Making magic

How important do you think is it for guitarists to know the history of their instrument?

“I think it’s the same in any artform, whether it be painting, poetry, or whatever. People who are into doing something truly great study the past masters. It’s partly just because of obsession, but I made it my business to find out what Les Paul, Django Reinhardt and people like that were all about, and I think young musicians will always do that.

“I can’t imagine a really great guitar player not knowing those things. You really need to have heard Les Paul - not just him whizzing up and down the neck playing really fast. You need to understand what he was about and the technology. Understanding the context of it is a fascinating thing.”

Perhaps the pinnacle of technique is when reacting to emotional responses becomes second nature…

“I think that’s what everybody is really looking for in an instrument. That’s what I understand about John Coltrane and Jimi Hendrix - there’s no gap between the impulse and the expression. It’s about trying to make the instrument invisible, at least during improvisation, anyway, which kind of goes against a lot of what some people think being a musician is about (the worship of the instrument). It’s the closest thing to what we understand as being magic, that I know of - that improvisation between people when in a split second someone reacts to someone else is pretty magical. The guitar is a conduit.”

I think many would agree that there’s something magical about guitars…

“There’s a lot about the guitar that is different to other instruments - the fact that electricity is involved and the really fabulous colours! One of the benefits of learning the guitar, for me, was that it was something where I could be on my own and just fuck everybody off and do something really engaging on my own. I feel very lucky to have found something that’s been a lifelong obsession, let alone get paid for it.

“It’s a great thing if you’ve got an identifiable style. As Chet Atkins said, ‘If your mother hears you playing on the radio and she knows it’s you, you’re a good guitar player’. There’s a lot to be said for that.”

Johnny Marr’s latest album Call The Comet is out now.

Rod Brakes is a music journalist with an expertise in guitars. Having spent many years at the coalface as a guitar dealer and tech, Rod's more recent work as a writer covering artists, industry pros and gear includes contributions for leading publications and websites such as Guitarist, Total Guitar, Guitar World, Guitar Player and MusicRadar in addition to specialist music books, blogs and social media. He is also a lifelong musician.