James Holden: "I got really bored of making music. But the moment I discovered modular and Live and Max/MSP, it all opened up again"

Two decades into his career, James Holden is still searching for new ways to make electronic music sound human. We visit him in his West London studio

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

James Holden’s career has seen him embark on a decades-long journey from solitary mouse-clicking towards the spirit and humanity of live, improvisational and collaborative musicianship, reimagining the act of electronic music-making in the process.

It’s no mean feat to capture in binary code or analogue waveform the raw and unguarded magic that happens when fingers meet keys and sticks beat skins, but Holden seizes that spark through modular synths, DIY recording methods and self-designed software. Breaking free of the shackles of grid-bound, DAW-centred music creation, he fashions living, breathing productions that poke electronica’s pallid veins with a life-giving blood transfusion.

When we first interviewed Holden - all the way back in 2006 - he was using Jeskola Buzz, a free, tracker-based software environment, to write his debut album The Idiots Are Winning.

If that record found the producer in something of a subversive mode, slicing and dicing the rhythms of trance and techno under his PC’s micro-edit microscope, its follow-up, The Inheritors, saw him flipping the script entirely, rejecting the era’s fashionably sterile minimalism in favour of deliberately disjointed timings and distorted sonics, a loose, messy and chaotic aesthetic that sounded brilliantly strange and felt thrillingly human.

A decade’s passed since that release, and in the meantime, Holden’s further embraced the ethos of humanization through a visionary collaboration with revered Moroccan musician Mahmoud Guinia that pushed the capabilities of his modular towards an improvisational synergy between traditional Gnawa music and the pulse of trance-inducing electronica. This was followed in 2017 by perhaps the apex of his career-long pursuit of musical anthropomorphism, a freewheeling and cosmic synth-jazz bacchanal recorded live in one room over ten days with (almost) no overdubs, alongside a band of instrumentalists dubbed The Animal Spirits.

Holden’s latest full-length project is a starry-eyed voyage into new sonic dimensions, fittingly titled Imagine This Is A High Dimensional Space Of All Possibilities. A joyfully acid-tinged campfire synth-along, the record finds Holden pairing hallucinatory electronics - sounds produced by a modular rig, broken Prophet-600 and custom sequencing and synthesis environment, designed in Max/MSP and housed in a 3D-printed computer - with a riot of live instrumentation contributed by the man himself (drums, piano, a childhood violin) and a varied cast of collaborators.

Both musician and machine-builder, for Holden these two practices are inextricably linked

Once laid down in marathon live takes, recordings were scissored and stitched together in software before being piped through a circularly arranged, ragtag assortment of speakers and recorded once more, essentially mixed down in physical space. The record’s twelve sprawling tracks recall by turns the motorik thud of krautrock and the jaw-swinging fervour of ‘90s rave, the unrehearsed brio of folk music and the dizzying anarchy of free jazz, chillout's uncanny drift and kosmiche's interstellar twinkle, all the while preserving the mesmeric arpeggios that have stimulated Holden's music from the very beginning.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Both musician and machine-builder, for Holden these two practices are inextricably linked. Many of our tools lead us down conventional paths towards predictable outcomes, but Holden arrives at new ideas by designing his own: as soon as an instrument’s built, though, it’s ready to be taken apart, reassembled and redeployed, as he continues his search for sonic imperfection. In Holden’s hands, inanimate tools are reborn as living systems, as the acoustic and the electronic, the digital and the physical - the man and the machine - are united in sound.

We visited James Holden in his West London studio to find out more about how the new record was made.

When did you begin working on the material that would become the new project?

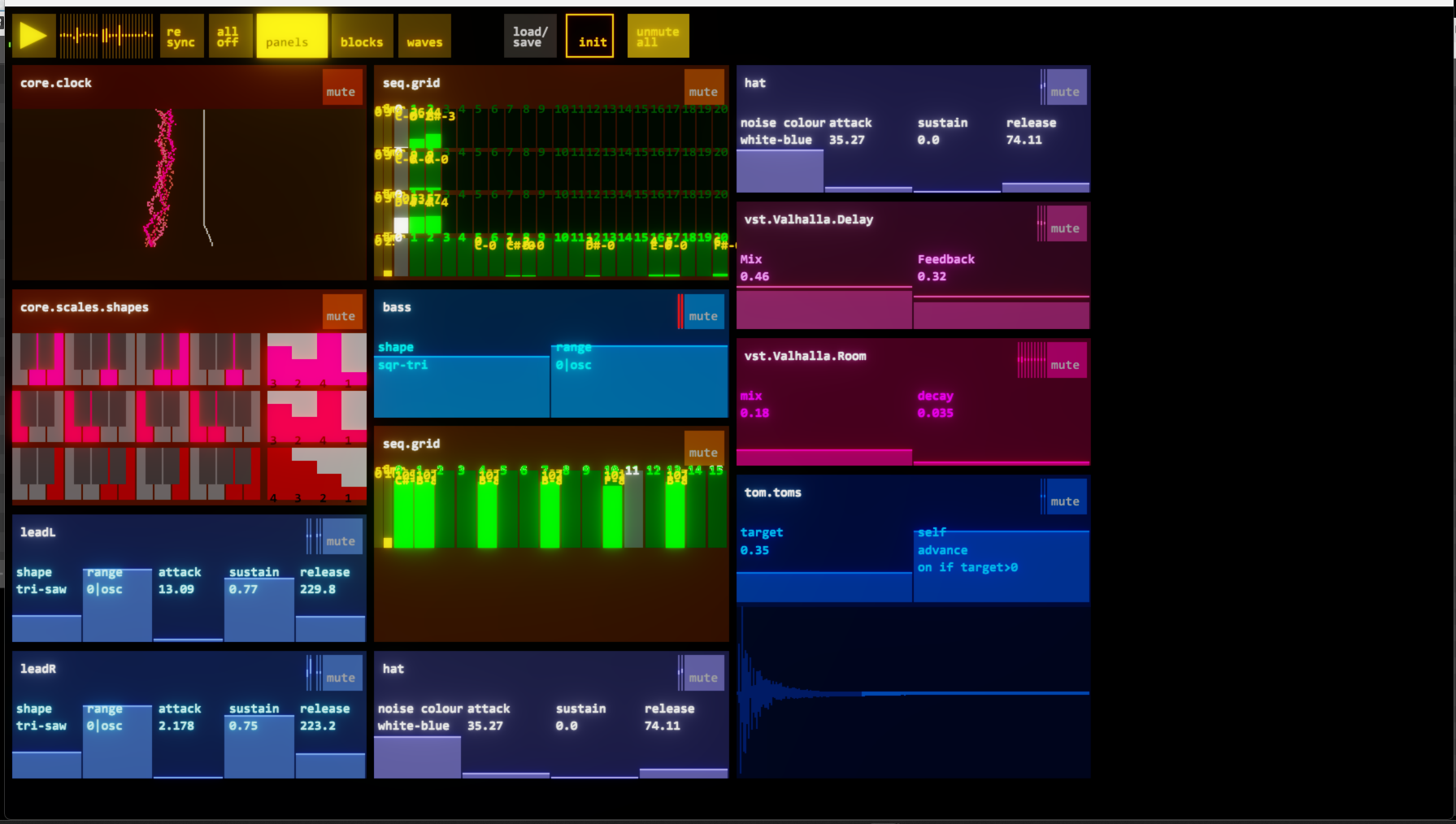

“The first bits of it came about three or four years ago. I've got this continuous ongoing project to make a big, ridiculous Max patch for playing live music in. When it started, I was using Ableton and dozens of Max for Live devices.

“This was when I was doing the Animal Spirits album, and during the first show we did for that, my Ableton took five minutes to load the set, it was just ridiculous. I had a high-end laptop at that point, and it was just melting under it. So I realised I had to change how I was doing it.

“I started building this big Max patch with all my little sequencers, my weird little synths and stuff. The idea being that you could improvise live with it. I'm up to version five now, I've been through all these different iterations. The previous version was what I was using in my collaboration with Waclaw Zimpel - he’s a Polish clarinet player, electronics kind of guy.

I start designing an instrument and then the songs come out by accident as a result

“What I found is that I'll start working on something - I was making a string synthesiser kind of thing - and then you're testing it and you're playing, you're tweaking the design of the software, but it's leading you to ideas, and then two songs will come out of that. That’s a really long way of saying, as I fiddled around with my software back then, it was almost like half the ideas for the album were things that started off as like, ‘I'll just see if the new synth I've made works properly... oh, it doesn't work at all, great!’ And then that's the idea for the song.”

So the ideas come out inadvertently while you’re working on the process and the tools behind them?

“Exactly. I find it quite hard to sit down and say, now I'm going to write a great album. I find that really daunting. I usually sneak it up on myself, like I start designing an instrument and then the songs come out by accident as a result. It’s weird - sometimes I'll go in the studio and something will come out by itself, but the process and the method of it is really important to me. I have to have some idea of like… what am I trying to do with the sounds today? That really gets me over the hump of starting.”

When did those ideas begin to take shape?

“It's just evolved gradually. There was a time when I was making music in Cubase, and trying to do it in the way you imagine people make music in a sequencer: loading it up, thinking what I want to do, finding the right noise to start… and I got really bored of making music. There's a little period of my stuff that I can't really listen to, that I'm not that into.

“It all got a bit stiff, because I was trying to do it in this traditional DAW way. But the moment I discovered modular and Live and Max, it all just opened up again, I started really enjoying myself. If you do things the way everyone else does, you’re gonna get the same results everyone else does. It’s really, really good to mess with your process.”

Tell us about your studio space?

“The studio’s a half hour walk from my house. We got really lucky, and we managed to get a little ex-industrial building really cheap. It’s a long story - some venture capitalists were involved. [laughs] So I've got this little room, and it's fucking freezing. I can't really use it right now because the electricity I need to heat it is too expensive. So I've got my computer and my synths set up on the dining table at the moment.”

You’ve said that your set-up for this album was fairly minimal, just two synths, the modular and the computer. Could you walk us through that set-up?

“The big thing I was using the most was the Tor modular that I was using with Waclaw. There's a lot of plumbing going on to enable the digital control of everything, but really, it was just a bunch of filters, a few analogue delays, a resonator, and a few different kinds of saturation. I had it set up with a MIDI control matrix, so I could patch anything into anything. I was using my Max patch to drive it all. About 80 percent of what you hear is that, basically.

“Then there are a few other little bits, I've got a Korg Mono/Poly, which is on a couple of tracks. Then there’s a Prophet-600 in one or two moments, which is just this magic thing - I turn it on and it's good. It's either ‘that’s amazing!’ or ‘that’s not working’ immediately - it’s such a binary kind of synth. I love it so much, the tone of the Prophet is really nice. Mine's broken, so one of the voices is a bit wonky, and it adds a bit of life when you're playing it.

“This room is where I record everything. It's not super big, but it’s got an interesting shape, and it’s got quite a nice room sound, as I've treated it a bit. The room is a big part of the record. Luke Abbott recorded his last album here, Translate, and we evolved this technique of putting every sound in the record through its own individual speaker, more or less.

“That's the idea - so I'd fill this room with speakers. Behind me, there's a couple I found behind the bins in the industrial estate. Then I had some nice old Tannoy monitors, and there’s the monitors that I use up here, a couple of guitar amps, a bass amp, a rotary speaker… and every sound goes through one of these speakers in the room, and then right in the middle of the room, there’s a pair of Coles ribbon mics, a Blumlein stereo pair.

The way I make music is to try and set it up as a living system where everything's moving by itself and interacting with each other, but I can steer it

“Basically, you get the sound right in the room. It really suits me, because the way I make music is to try and set it up as a living system where everything's moving by itself a little bit, and interacting with each other, but I can steer it. So this arpeggio affects that arpeggio, and they're through speakers at opposite sides of the room, and you get this real spatial sense of what's going on. So you kind of mix the record in the room, just by making it sound exciting. It's so different to mixing on speakers, because by separating the sounds out, it gives another kind of separation.

“So we’re just doing it in the room, and doing it with a lot of quick hacks and hardware, like: that part’s sounding too direct, so I’ll turn the speaker around and point it the other way. I've got mics out in the foyer as well, to get a longer reverb on everything.

“That was the secret of the record: I’d do these long live takes with my synth, mostly with the modular and my computer stuff, playing it all through the room. Then you've got this stereo mic recording of it, which is full of atmosphere. It's got the clonks - if I get excited, and I knock something off the table, that's in there as well. It builds your mix for you.

The whole thing has this real sense of space, a sense that something happened in a room and I recorded it, rather than some guy with a mouse

“What I've been working on the last few years is a lot of stuff where real instruments and synths are in the same thing. So you have to bring the synth into a real space somehow, and this is a continuation of that process. There were less real instruments in the mix on this record - quite a lot, but not as many as previously. But the whole thing still has this real sense of space, a sense that something happened in a room and I recorded it, rather than some guy with a mouse, which is a different feeling when you listen to it.”

It’s a really cool idea, summing everything together in physical space rather than in the computer.

“Yeah. You can use the individual channel recordings underneath like you’d use spot mics, to bring some clarity. It’s such a great way of working, I love it. I told Waclaw about it, and he went out and bought like a 20 pound digital amp off eBay and found some cheap speakers in junk shops, then messaged me three days later saying ‘James, you changed my life!’ [laughs]

“Electronic music exists in this flat, digital, virtual space behind the speakers. It's not like when you listen to an amazing recording of a jazz band on a great hi-fi, and you can hear that goes there, the bass is at the back, the drums are over in that corner… you can hear the room around you. But in electronic music, the only room you hear in it is very often your own. It's all just pushed to the front of the speakers. It’s nice to flip that idea around.”

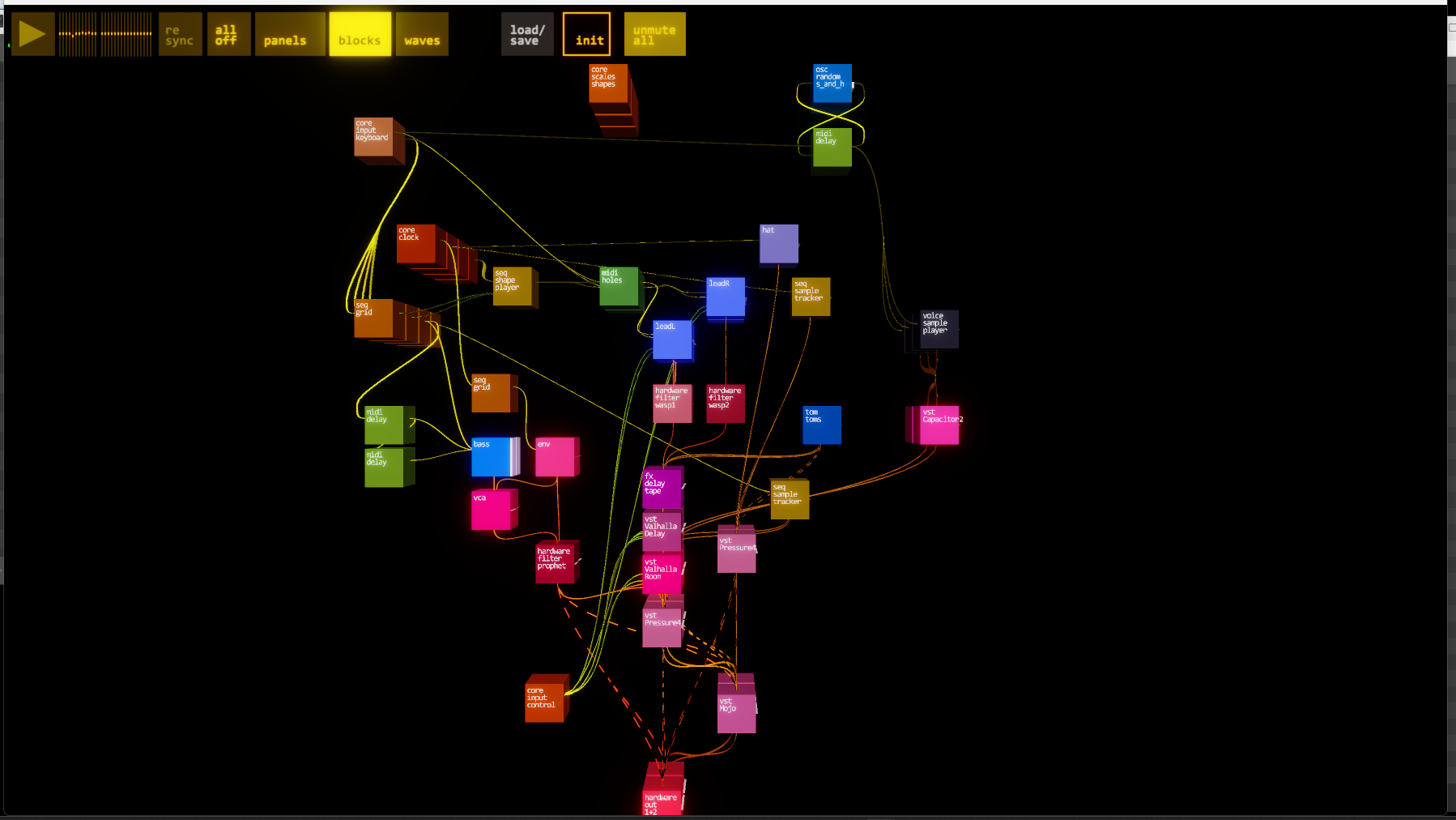

Could you talk us through the Max patch you mentioned?

“So the old version was really clunky to use, but the new version looks fucking cool. There’s these little cubes in space that you wire up and then they represent either software or hardware modules. The modularity of it is the thing that you hear the most. Everything can modulate everything, but also I made it so you can assign parameters as if they're like birds on a spring, flying around the position of the knob. They flock, and you can have different flocks interacting.

“For example, on the track Trust Your Feet, it's got this thing - there's an LL Cool J record where he talks about ‘the rhythm is the bass and the bass is the treble’, or something like that. This track is that kind of idea. There’s a part which is a high arpeggio, but it's also the bassline and it swings between the two.

“I've got this transposer that works in a scale. But the transposition, if you listen to it, you can hear that when I turn the knob to swing it down to a low note it swings past and overshoots, and oscillates around, because it's a modelled weight-on-a-spring effect happening off my parameter input.”

Kind of like a pendulum?

“Yeah, exactly - you turn the knob and it follows as if it's following it on a spring, and then it overshoots and goes too far and then springs back and gradually dampens down. My car’s shock absorbers are fucked, and it's kind of the same effect.

“Because then you're thinking, I'm going to drop the bass, but you know that it's not going to respond in this totally predictable way. And then you're responding to it, and it gives you surprises, which changes the music. That song is different as a result of having that effect in it, because it led me to play it in a different way.

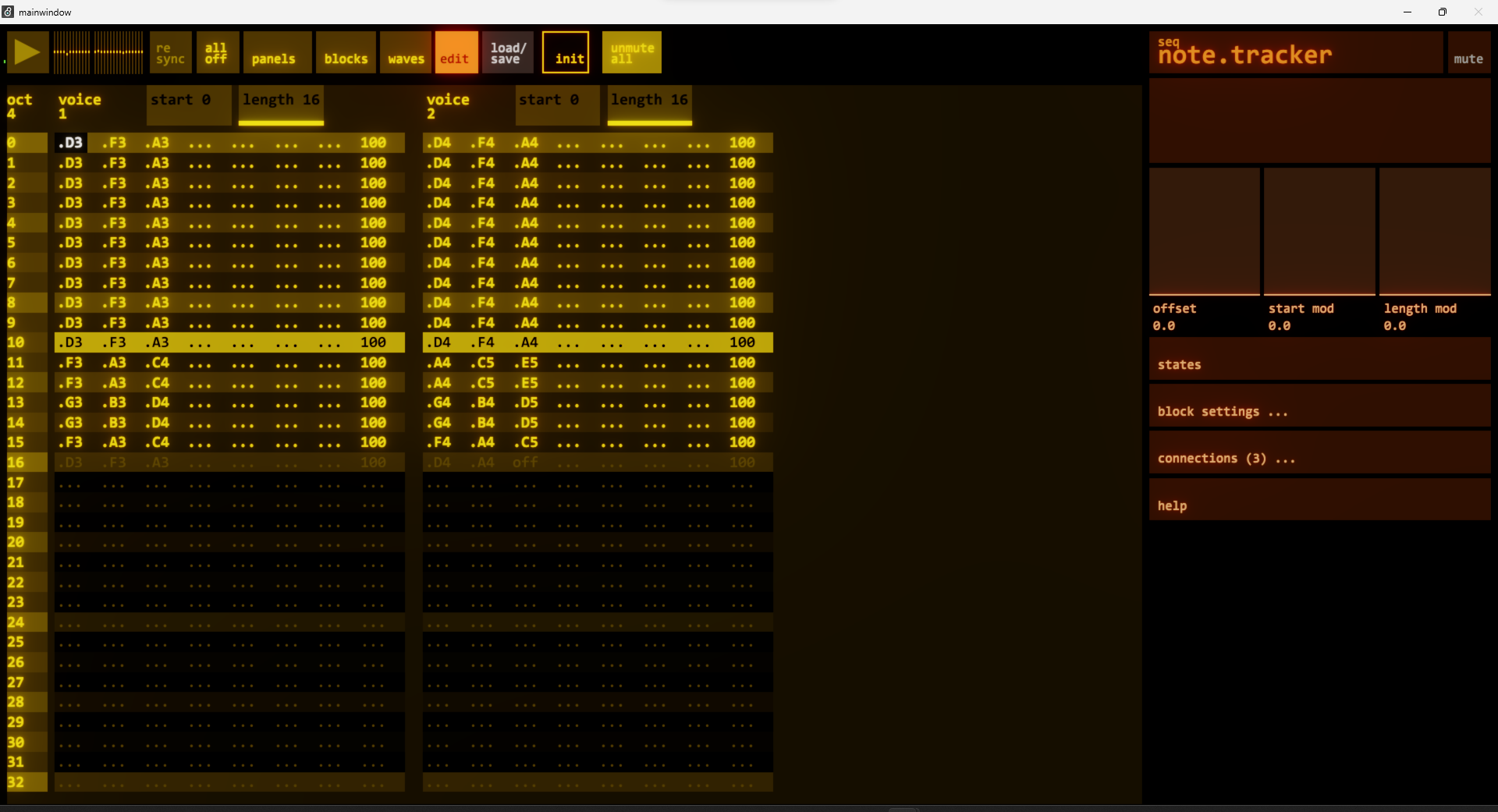

“I guess most of the important stuff is my sequencers. I try to program sequencers that are separate from the scale… so the sequence has a shape and a rhythm in a scale, and then you manipulate those things separately. So you can transpose it, but in the scale, or change the shape or add ornaments and stuff to it.

Luke's got this incredible Max patch that understands keys and modes. His Max patch knows more music theory than I do

“Me and Luke talk a lot about different ways to make arpeggios, and ways to make the computer understand the music it's doing. Ways for the computer to augment your musical abilities. Like I'm a shit pianist, I can't do the arpeggios that I want to do, ever - that's where it comes from. But Luke is actually way ahead of me on this now, he's got this incredible Max patch that understands keys and modes and stuff. His Max patch knows more music theory than I do.”

Do you two share patches between you?

“A bit, yeah. Leafcutter John, some of the patches he's shown me have really opened the door on how to do things or approaches or whatever. But also, ideas go backwards and forwards. Sometimes Luke will suggest something and that becomes a little plugin that we use between us. Waclaw is really good at suggesting things - he’s not great at making Max patches, but he's really good at suggesting things that I can do in 10 minutes, and they're like, fuck - that's such a good idea.

“He had this idea for a gate that works on pitch. Because he plays a clarinet with a mic inside, so you get a very clean signal. This gate lets you select the pitch: you've got loads of Ableton channels with the clarinet going in and then it will only let through the Cs on that channel, and the Ds on that channel, and so on. Then he can put them through different effects or different loopers and stuff. He was like, can you do this? I was like yeah - it’ll take 10 minutes. Then he made an amazing record with it. It's really satisfying doing that kind of stuff.”

Aside from the software you’ve designed yourself, what other plugins do you find yourself using most frequently?

“There was a time when I was really into checking out all the plugins and I was really lusting after all the synths, and I suddenly realised that every time I bought a plugin I just ruined records with it. It was a really weird psychological mess going on. So in terms of sound generation or music generation, I don't think I used anything that wasn't Max or a synth.

“But in terms of mixing, there was one set of plugins that completely changed my life, mixing this record. I've got my 500 racks, and behind me there's a nice analogue desk, just to your right is another nice analogue desk, and I’ve got some really nice preamps here. But I didn't use hardly any of it, because I got these Airwindows plugins.

“This guy Chris at Airwindows, all his plugins have wack names on the sliders, they don't have a proper interface, and there's no bullshit to any of it. He's really into this dogma of not over-processing. If you're doing stuff in digital, you're losing stuff at every step of the way. He explains the maths on his blog sometimes, and it's like: oh, I should have realised this 20 years ago! When you've got 20 plugins on a channel in Ableton, it always sounds like ass. It’s never good.

“He's got some really nice distortions and tape emulators and stuff like that. But there's not a picture of a tape machine on it: it just sounds good. Also, these channel console plugins - you put one on the end of every channel, and then one where the channels get summed, a different plugin. It does this transform and inverse transform that means the summing is no longer linear, digital summing.

When you've got 20 plugins on a channel in Ableton, it always sounds like ass. It’s never good

“I don't know if it was that, or just his approach of having lots of different distortions throughout the signal chain, just subtly rounding it off. I found my mixes came together quicker. I was much happier. I think I'm just really happy with the tone of this record. I guess I can't put it all on the Airwindows plugins, because it was quite a luxury recording process: nice room, nice mics, nice speakers, nice synths, nice preamps, nice interface. But in the end it was these basically free, open-source plugins.”

“He’s put his code up as open-source, and I'm starting to learn a bit by picking through it and understanding how he's done various bits of it. It’s just the way he presents it. It's like the opposite of… the plugin industry is weird, isn't it? Waves has this permanent sale on, but then everything sounds the same, it just has a different interface.”

It’s just the sheer volume of them these days. With that much software coming out, it’s hard to know what’s good and what isn’t.

“Yeah, and you've got these massive venture capital companies and funds buying into this space. They're extracting value from a sector but they're not necessarily adding any. Their interests aren't necessarily the same as our interests.”

It’s these one-knob plugins you see in YouTube ads which seem to be taking over - the ones that promise you the cheat code to music production.

“Exactly. You can buy this plugin for 100 bucks, and it's the cheat code to music… then everyone else has got it, so it's worthless. We're at this weird point. There was a time 20 years ago, when doing something that sounded like it was made in a big studio, or doing impressive graphics for your album cover or video or whatever, that seemed impressive. It looked like you'd spent money, like someone had put money behind it.

Things that look DIY are actually cooler, and a human touch is nicer to see. It’s all about the humanity now

“But we’ve got to the point where there's so many ways to fake the appearance of having put money behind things. I quite like the idea of: what if money behind something isn't a good thing? Things that look DIY are actually cooler, and a human touch is nicer to see. Now we've got AIs that can do this kind of shiny bullshit. It just has zero value. It’s all about the humanity now.”

You’ve said before that you made the shift to Reaper for recording and mixing a few years ago. What is it about the software you like?

“I did, but I've come back actually. I loved mixing in Reaper, because it was just a tape machine to me. I didn't really know how to do any quantized editing, and deliberately didn't teach myself quite a lot of Reaper. I just used it as a mix console. It saved my ass mixing the Animal Spirits record.

“There was a super interesting thing on Reverb about Talk Talk’s studio methods a couple of weeks ago, and there's a quote from Mark Hollis where he's saying there are two things in music: there's the raw, impossible-to-fake, beauty of live performance, and all that richness. But that can't access the detailed, subtle, well-judged things that just fall in the right place and the serendipitous combinations that you get from studio arrangement.

I realised what I really wanted to do was crash live recordings into each other and enjoy the serendipity of things lining up in a different way

“Reaper is really good for recording - for me, anyway - and Ableton is really good for arranging things. But I found that I started trying to do mixes in Reaper for this record, and I realised what I really wanted to do was crash live recordings into each other, and move my takes around and enjoy the serendipity of things lining up in a different way. But it was 10 percent slower to do that in Reaper, so I just went back to Ableton and put it there.

“Ableton is really good for quickly moving shit around and lining it up. I love it for that. It's alright for mixing in, but you find yourself missing that proper big mixer view.”

Could you talk us through some of the most prominent effects used on this album, whether that’s hardware or software?

“It’s a mix. I guess there’s a bit of Valhalla reverb. That's my go-to, if I've not got a recording of some room reverb, that’s what I’d use. His Room or his Plate plugin. A few impulse response reverbs, a couple of my own impulse recordings and a couple of downloaded ones.

“I still use this old SIR2 convolution plugin, because to me it sounds better than all the fancy new ones. I don't know what else… mostly it’s my own delays. I built a really nice delay in Max with a really nice kind of chorus-y modulation to it - that's most of the delay you hear on the record.”

The press release says that you were effectively sampling yourself for this project. Is that a process you’re drawn to, recording loose jams and ideas and then piecing them together later on?

“In the past I would generate huge long takes and then get overwhelmed trying to pull them apart. But I think a little bit of collaborating with people is that I've learned to get to what I want a little bit quicker. I’ll fuck around for a while first, and then I'll press record.

If I play drums or piano, it's always got to be a rescue job. But that makes it quite fun - some of my accidents are the best bits of drumming on the record

“I've got the judgement of when's the best time to press record a bit better now. It's the tiniest skill, but it makes such a big difference. Because if you're overwhelmed by three hours of takes you might miss the really good bit that you did. Because I'm not that good at instruments - I'm just a bit clumsy - if I play drums or piano, it's always got to be a rescue job. But that makes it quite fun, because you find something serendipitous, like… you didn't mean to play that note, but it was good, wasn't it? Some of my accidents are the best bits of drumming on the record.”

The press release mentions that you played piano and violin for the first time on this record. What do you think was stopping you from doing this earlier?

“You’ll probably have to ask my therapist. [laughs] My dad taught himself piano and he taught me piano, and then I learned violin at school. There was a bit of pressure from my family, like - you should learn proper music. So I didn't fully value it. I stuck with the violin because I was a good boy, really. I wasn't super enjoying it as a child.

I had this residual feeling of discomfort with the idea of playing it. Then I realised that actually, I'm a different person now

“It was only afterwards that I discovered Tony Conrad or John Cale or Jean-Luc Ponty, the cool violin players. It took me 10 years to find some cool violinists after I'd stopped playing violin, but even then, I had this residual feeling of discomfort and embarrassment with the idea of playing it. Then I realised that actually, I'm a different person now, and I can pick it up and really enjoy it. It’s funny - you change as you get older, I guess.”

You told us in 2018 that for the Animal Spirits record, you had a ‘dogma manifesto’ of rules that you later ended up breaking. Did you take a similar approach with this record?

“No, I didn't. It was hard having rules. I only broke them a little tiny bit - two or three edits. But as a consequence of the rules, I spent all of my budget for that record on getting everyone in the studio for a week and a half. I couldn't afford to do it again, but at the end of that week and a half, most of it was great, but there were a couple of songs where I didn't play as well as I could have.

“There was nothing I could do about it, I was stuck with it. That was a really horrible feeling. In the end, I made sense of it, but it was really difficult. So this time around I didn't make a rod for my own back in the same way.”

I guess working with computers, it’s easy to get used to the idea that anything can be edited.

“That's another benefit of the Airwindows plugins. Because I'm using them instead of putting everything through a desk, and it means I can just load stuff up and not have to spend 20 minutes trying to line the faders up to where they were before.

I don't think I've ever got a mix right in a day, ever, so a console is actually quite annoying to me for that reason…

“When I’m composing, the modular is great, because it takes away that recall, so it makes you commit to a take because you don’t think you can come back and recapture the vibe tomorrow. But in terms of mixing, I don't think I've ever got a mix right in a day, ever, so a console is actually quite annoying to me for that reason… [laughs]”

Could you tell us about some of the field recordings you incorporated into this record?

“We just went on some adventures with one of my friends, this guy who records as Hidden Rung. We went wandering around with him. They have sound mirrors on the coast, near Kent and Dover. These big domes that were for listening for aeroplanes, concentrating sound before they had any electronics to do it. We did some hollering in front of them, but it was really windy so that didn't work out. But then we just found a nice beach, and he put the recorder down and it seemed really serendipitous - the kids, the beach, the aeroplane.

“There’s another one where me and Gemma just got drunk and went for a walk in the village my parents live in, down by the canal, recording owls and stuff like that. There’s an owl, a sheep, and a train going past. The one with the train going past, again, it was a technical experiment - I put this Doepfer phaser in my rack, I was just seeing if I could get something good out of it and did this little live jam.

“Then I dropped the recording of that live take into Reaper where this field recording was, and there's a bit where I'd killed the synth with the filter and then brought it back in half a bar. And in that gap, by coincidence, there's a train sounding the horn, and then the music starts again. Okay, so Jesus says I've got to leave it like that… [laughs]”

The album is described as a ‘continuous sound collage’ and it feels more like one coherent journey, as opposed to a collection of discrete elements. What is it you’re drawn to about that structure?

“I don’t know what it is. I've always liked that, that magic radio kind of feeling. I grew up when you could find weird radio stations - that was the most exciting music I could hear for a little while in my youth, because I didn't have access to much else. A lot of the records that were a really big influence on me growing up, and also those that I was thinking about for this record, were Future Sound of London, The KLF, and stuff like Negativland as well.

The only way I can really conceive of putting an album out is if it's like a whole thing - a world, an idea, a concept, a story. It’s quite important

“I really enjoy that as a way of listening. People say albums are dead. You need a reason - if it's just 10 songs on Spotify, I don't know if it necessarily needs to be an album. But if you make it a trip, then you've tied it all together, and no fucking corporation can pull it into little bits and atomize it. The only way I can really conceive of putting an album out is if it's like a whole thing - a world, an idea, a concept, a story. It’s quite important.”

It sounds like you were reaching quite far back in terms of your musical influences this time around, back to the teenage years almost?

“It was a little bit. I'm not really sure why - it wasn't a super conscious decision. In terms of what I've been listening to, it's not like my listening tastes suddenly changed or I went back to digging through old records or anything. I guess lockdown did remind me of what it was like being a teenager: just waiting and waiting for something to happen.

“That put me back in the same kind of headspace and made me think about that. What I'd be getting out to, or what I wanted to do when I got out. Raves, and that ravey end of things, at a certain moment, when we were locked up and miserable, did seem like the ultimate dream: getting out into a sweaty, loud environment again.

“I learned to make music and made my first records on this thing called Jeskola Buzz, and my Max patch began to get to the point where it started to remind me of the feeling of using that. It leads you towards that kind of music slightly, as it’s a tracker interface. In a way, I went away from that stuff because of the way life took me.

Some DJs I've met, they imagine that the whole crowd is full of the worst, dumbest, most basic bitches possible, and then they play for that! Why?! Is that the job you wanted?

“When I started, I didn't really know about DJ scenes. There can be quite a conservative set of values and culture around them. I found it quite a difficult culture shock, putting records out and then meeting people who were evaluating them in a context that I didn't understand or agree with. And then being a DJ, and getting that very direct feedback off the crowd continuously every weekend. It really colours how you think about music: what you dare to do, what you want to do, or whatever.

“Coming out of that, doing the collaborations and the Animal Spirits record, it meant that I was disconnected enough from that world. It was almost like I got back to that teenage headspace. I know a few DJs that I really like - we saw Oceanic a little while ago and it was fucking amazing - so I'm still connected, but I'm not so in deep that what people might sneer at, or think is cool, really registers with me. I'm not letting that in, I'm not having it. That's put me back to this naive state of: I'll just do what makes me feel excited and see if it resonates. It seems like it's working actually, so I'm quite relieved… [laughs]”

That subconscious assumption of how something might be received can really fuck with your creativity.

“Yeah, definitely. You can hear how conservative records are when they're aimed at a club dance floor. I was talking with Tom Ravenscroft about DJing, and I was saying that I like to imagine that there’s someone just like me in the crowd.

“Some DJs I've met, they imagine the opposite - they imagine that the whole crowd is full of the worst, dumbest, most basic bitches possible, and then they play for that! Like, why?! Is that the job you wanted? It just boils it down to the lowest common denominator of nothing. An AI can do that, so we don't need to do that anymore.

“It’s part of my journey as a human that when I started, what other people thought really affected me. It still does, but now I see that it's really important to put a boundary up. There are plenty of people who think just like me, and it's really nice to think I'm just making music for those people, because I can really connect with them. They'll get it.”

Listening through your previous albums, to me they sound more minimal than the new record, which feels much busier sonically. Has that been a conscious transition?

“That's funny, because in a way, this one is still quite simple. I'm putting together the live set now and some of the tracks don't have very many channels in. I guess how I wanted to develop was to learn to make my arrangements more interesting.

“As someone whose brain is wired a certain way - I'm waiting for a diagnosis from the NHS, but we'll see - I have difficulty concentrating most of the time, but then when I get in a flow, in a trance, it can go for 12 hours, and I'm on the verge of wetting myself or passing out from hunger.

“For me, it pushes my buttons so much to just play four chords on the piano for an hour, or just sit and listen to a drone for a while. The Inheritors, I was super happy with, but there was maybe a slight one-dimensionality to each track, because I was so happy to just exist in this one place that I didn't even consider that it could have a left turn or that it could go off in a different direction. That was the conscious part of this record.

I'll never be able to do a bridge or a middle eight or a chorus in a song, I just can't. That transition breaks the trance flow, and it just kills it

“I'll never be able to do a bridge or a middle eight or a chorus in a song, I just can't. That transition breaks the trance flow, and it just kills it for me. When I was in high school music class, we had to write a piece. Me and my mate had a Casio keyboard, and me and my mate had written this thing that had a verse and a chorus. And I was playing the verse, and I realised I don't know how to get to the chorus… like, it just doesn't make sense! We were just playing the verse for like 10 minutes and the music teacher was like, you’ve got to stop now. [laughs]”

Could you tell us more about the photographs that inspired this record?

“There’s a photographer called John Stezaker. Looking at his pictures and talking about that stuff with Luke and Gemma was my way of working out how to make something that’s minimal but has a change of direction or intersection or juxtaposition in it. He does these pictures where there’s like an artist’s stock photo with a cliff face just cut across it, or something. The two make these quite magical coincidences. They’re completely different things crashing into each other, but they expose the other thing.

“The first single off the record [Contains Multitudes] is definitely the best example of that. It was this Orbital-y, psy, kind of banger, the first half of the track. I was just like listening to it as a loop and playing it on the modular and thinking, this doesn't have a beginning or middle or an end yet. But I could hear this kind of Latin piano jazz, something in the mould of Pharaoh Sanders’ version of Olé. I've got a £20 pound Casio keyboard and just picked it up and came up with the second half of the piece on that on the first go. Then luckily for everyone I re-recorded it on a proper piano.”

To my ears, this album feels more positive and optimistic in tone than some of your others. Is there any truth to that observation?

“Yeah, 100 percent. It was a bit deliberate. Everything was shit, the whole world was shit. I thought if I'm gonna put records out, and enjoy the privilege of putting records out, then I want them to be something that brings some joy to everyone. What's the most giving and positive thing I can possibly do with it?

Everyone was doing very clean, minimal, tidy stuff, and I was just distorting everything through tubes and putting it out of time on purpose

“The Inheritors was a reaction against the world I was in. It was a bit of an aggressive act in its own silly little way. Everyone was doing very clean, minimal, tidy stuff, and I was just distorting everything through tubes and putting it out of time on purpose. But I didn't feel the need this time. I'm not fighting anyone now, I'm quite content. You have to be brave, somehow, to be open and naive and positive. It feels more exposing in a way, putting something like this out. If everyone had hated it, I would have been really upset this time around. [laughs]”

I suppose people often respond to vulnerability in music.

“Yeah. When you listen to music, and you get something deep out of it, what is happening there? What is it? I’ve thought quite a lot about that. When you're writing songs, you project things that are going on in your psyche onto the song. It's not necessarily universal, what everyone will get out of it. But it's surprising how much of it does resonate. It's a funny kind of process. There’s something on the Animal Spirits that I couldn't play the demo of without crying. But then by the time I'd finished it, it kind of leaves me emotionless. It’s kinda weird.”

There’s a real looseness to the timing in your music. I know you released the Humanizer M4L plugin a few years ago. Could you talk us through how you approach timing more generally?

“When I discovered the research by this guy Holger Hennig, who had done these studies about how human timing worked, it made me think about the way we approach recording. What he proved is that when people play together, there's a two-way feedback process in the rhythm.

“You can't fake that - if one person does it, and the other person does it afterwards, you've only got a one-way feedback process. That’s what led me to the dogma of the Animal Spirits, this idea that everything has to be recorded together. Because it's not just the timing where the feedback is interesting, it's the way people interact musically.

It's impossible for me to do a straight clock. Every part is a separate player who drifts relative to the other one

“It completely changed my approach to everything. It's still in there - sometimes I catch myself thinking, if you do it like that, it won’t be two-directional enough. I'm less dogmatic about it now. My Humanizer patch works, but you can waste a lot of time trying to make it work perfectly, or do everything by the book. So now in my Max patch, I have a version of that humanization running on everything. It's impossible for me to do a straight clock. Every part is a separate player who drifts relative to the other one.

“That fed into the idea of things being like flocks that could influence each other. This whole thing opened up a lot of my approach at the moment to things that resonated or reminded me of humanizing. It's interesting, the people who discovered it patented it, and they've licensed it to a software company now. So I can’t update the Max for Live patch, but they're gonna let me leave it up as is. It's a shame, but it'll be nice if they can make it into a package that's usable for more people with a less technical background. That could be really cool.”

You spoke in a recent interview about AI in music, and you mentioned you were concerned about where the recent developments could lead. Could you elaborate on that?

“In this country, Luddite is a bad word, isn't it? I read the Wikipedia article about them, and realised that it's one of these things where history is written by the winners. The Luddites weren't anti-technology. They just wanted technology not to take away their good job and replace it with a shit job that was dangerous and hard work and didn't provide any pay or give them any control over their conditions. But the way this country is run, they were beaten down by the army, because this country is run for capital.

“Broadly, AI is the same thing happening. You or I can’t make an AI, you need a fucking billion dollars to train them. Then when you’ve spent a billion dollars on training the stupid thing your shareholders want a return. It's just terrifying to me.

“Technology generally hands power to the people who can afford it and takes power away from another group. We have a shit government, America has a shit government, and we've already seen it happen. That's the thing with Spotify. What happened was big money found a way to short-circuit the whole music industry and reduce the price of music to nearly nothing. The major labels are fine, because they own a share of Spotify. The money people, the shareholders, are all okay. But we've seen our entire ecosystem get fucked totally.

The money people, the shareholders, are all okay. But we've seen our entire ecosystem get fucked totally

“When I started there was this broad middle of musicians, people who weren't super famous - they could go out in central London, no one would recognise them - but they were paying their mortgage and they were living a decent life. But that middle has shrunk by 90 percent, 95 percent. It’s shit. What have we gained out of that? All we've gained is Daniel Ek having a lot of money. I don't know what the answer is. But just being rude to people who like AI is definitely not the answer.”

It’s frustrating, because as troubling as the technology’s implications are, the creative possibilities are equally fascinating.

“I've seen some AI stuff which has been really interesting for music. There’s a Max device called nn~, which Luke was playing with. He was feeding in his drum machine and it was encoding it and then using the 1960s music dataset to spit it back out, but it was spitting out jazz drums that were playing his rhythm. I thought fucking hell, that's amazing. This style transfer stuff, you could play that, that could be an instrument, you could do a performance. The rules of music would apply.

It's funny that I try to build little living systems and sets of rules and make autonomous cybernetic music, but I fucking hate AI

“A lot of this other stuff, where you type a prompt in: I want a deep house track with a soulful vocal. There's no way for that to be a musical experience. I've seen some other things where the AI can let you pull the bass out of this track and the snares out of this track. To me, that doesn't look like music-making any more, it looks like scrapbooking. It looks like making a Pinterest. It's a different activity - it doesn't have that real-time, I'm doing a thing, I'm learning how to adjust what I do to get to a better result, kind of thing.

“You can't be a musician playing a black box. You can't do any kind of art playing a black box. The black box is just doing its thing. It's funny that I try to build little living systems and sets of rules and make autonomous cybernetic music, but I fucking hate AI - even though it's kind of trying to do the same thing - because it’s this inscrutable black box. If I wanted an inscrutable, impossible black box, I know some really great musicians that have really difficult personalities, and I could just have them round instead… [laughs]”

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it.