Hainbach: “I feel I make better music when I have to struggle with an instrument”

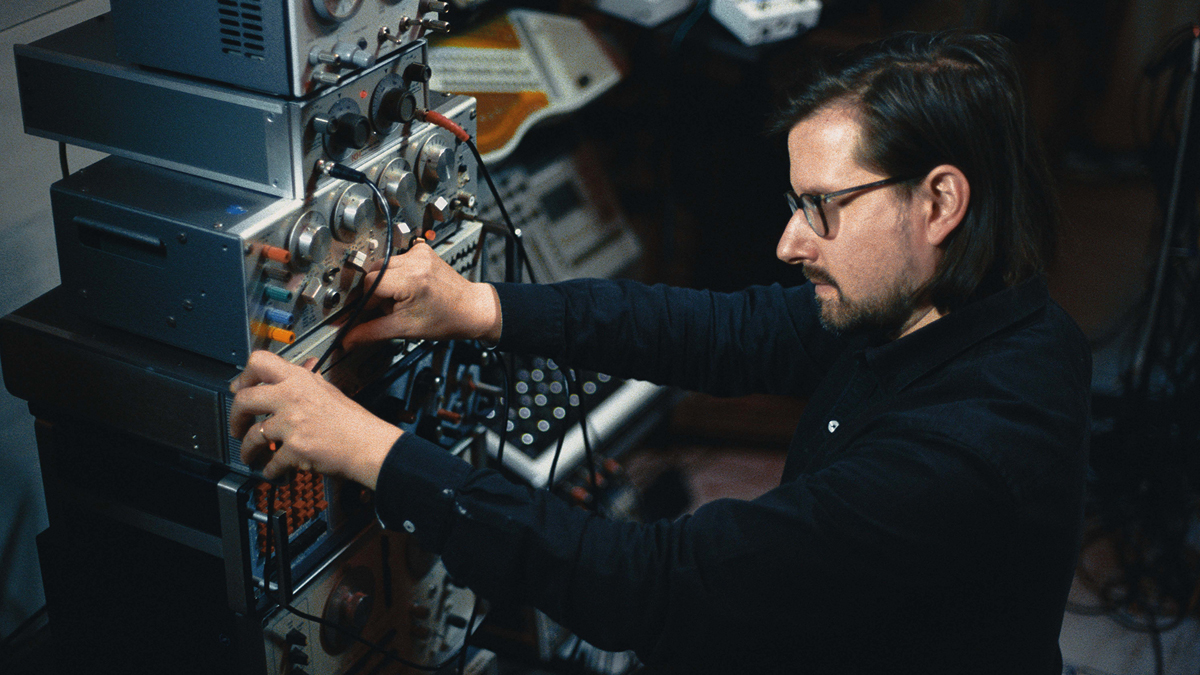

Motivated by a fascination for high-end research equipment and turning gear from old sheds and nuclear research labs into sound, Stefan Goetsch discusses his latest album Landfill Totems

Sitting on the periphery of the ambient-experimental genre, German producer Stefan Goetsch possesses an unrestrained enthusiasm for all things vintage.

Consumed since childhood by radio frequencies and sine tones, his releases as Hainbach typically consist of shifting audio landscapes based on the creative limitations of discarded gear taken from electronic landfill sites.

His latest album, Landfill Totems, typifies the producer’s approach to production and composition. Conceived from an art installation/performance based on three huge sculptures constructed from obsolete high-end research equipment, Goetsch went on a journey to discover their unforeseen capacity for creating immersive tonal meditations.

We understand that your love of electronic sound derived from the dial on a radio. Tell us about that early fascination?

“When I first heard John Peel on the radio and his cassette tape reruns from German free broadcasts I was suddenly hooked because these were sounds that I’d never heard before. It was very exciting to me and I wanted to make electronic music like that.

“At the time I was in a band and wanted to explore these things, but as a student I didn’t have money to buy a synthesizer. Instead I used a radio that had nice speakers and found that once you turned the dial all the way to the left you could hear all these heavily modulated sequences from the Euro signal.

“I started to play the dial on the radio with my left hand and the piano with my right, recording them through the left and right inputs of a cassette tape.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

What forms of music did Peel alert you to?

“In the mid ’90s I religiously adored everything that came out on Warp Records and Rephlex. I discovered Aphex Twin’s Selected Ambient Works, which completely changed everything for me and I started to look for sounds that came from that world. Except for one or two tracks that I’d programme out, the album had a sense of complete peacefulness, and that’s how I wanted to make music.

“I remember living in a small room at university filled with gear and just a mattress - I’d get up, go to the mixer, make music and then lie down and go into this hypnagogic dream state.”

Can you remember some of the gear that you used on those early experiments?

“I remember experimenting with radio and tape, but needed to get these sounds that I’d sampled onto my Casio SK-1 sampler, which could only store one sample and when the battery went out it was gone for good. Then I heard about synths that were supposed to be able to make almost every sound and bought a Roland JP-8000.

“Because it had the most knobs on it I thought it must be able to make all the noises I wanted, but after a while I realised I couldn’t replicate the exact 8-bit sounds made from the radio, crushed in the SK-1 and pitched down, but it was still good enough to use live.”

Presumably, you were never a fan of presets?

“I didn’t like any of the presets except for one supersaw string sound on the JP-8000 called Tron Strings, which was lovely. I’ve been a fan of synth strings ever since but my goal is to always make my own sounds and try to break the machines, so I found ways to get the JP-8000 to break up by overdriving it internally using feedback.

My goal is to always make my own sounds and try to break the machines.

“Then I heard about analogue synths, which were supposed to sound better and were cheap. By then, I’d moved to Hamburg and there was a small store nearby that I could get some lovely synths at decent prices.

“When I played my first vintage Roland SH-02, I realised that the JP-8000 was boring. I also borrowed a Roland Juno 60, which sounded great, but I was never a huge MIDI guy and was completely into treating sound and working with it in the DAW.”

What were you using for drum sounds?

“When I was still recording with a band I was using a CreamWare Pulsar system to record the full drum kit and learned to mix and record everything in my parents’ basement. I used Cubase 3.5 from 1998 and discovered all these fun plugins.

“The first drum machine I got was the Hammerhead Rhythm Station by Bram Bos. We actually worked together last year on a looper and iOS plugin called Gauss, so it was amazing to work with the guys who made one of the first software drum machines.

“I also found granular synthesis at that time, which became part of my musicology studies. I loved using the computer for granular processing and then putting analogue sound into it for further processing. That became my general direction for about 10-15 years.”

When did you first discover test equipment?

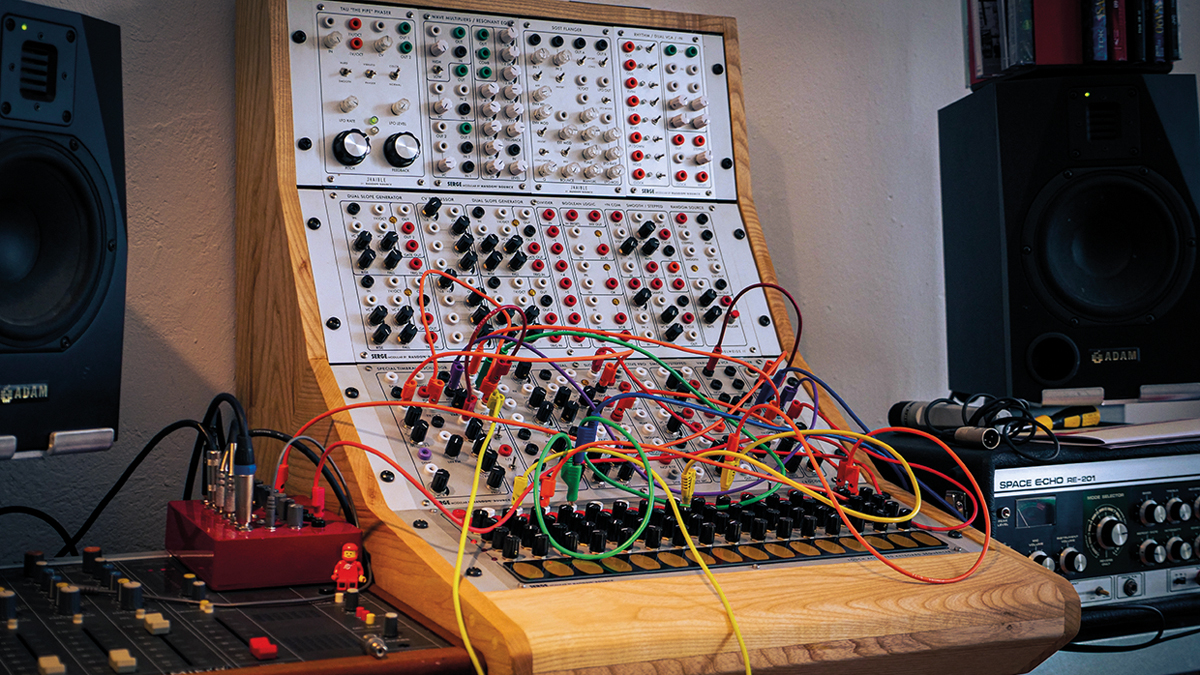

“I got deeper into weird synths and in 2011 heard of West Coast Synthesis and built my own Eurorack systems in that vein, but it felt weird constantly changing the modules because the creative process would never go into my muscle memory.

“Then I discovered Ciat-Lonbarde’s semi-modular systems by Peter Blasser, which are probably the furthest you can possibly go with modular. They’re actually fantastically playable wooden instruments built from art installations and paper circuits with beautiful names like the Plumbutter Drum and Drama Machine and the Cocoquantus.

When I played my first vintage Roland SH-02, I realised that the JP-8000 was boring.

“I took them to Rotterdam and played a show at WORM, which was in the same building as a small test equipment studio run by Dennis Verschoor called the Waveform Research Centre. That’s where I encountered the physical manifestation of making music with test equipment.”

We understand that your latest album Landfill Totems started off as a physical installation using test equipment?

“I was super-fascinated by test equipment but thought it would be impossible to find this stuff, then a few years later Dennis posted a buyer’s guide to making music with test equipment.

“I started to look for these on the German equivalent of Craigslist and found a guy who sold a vacuum tube sine generator from the 1940s and an oscilloscope. When I went to visit him on my bike I found that the sine generator weighed about 25kg, so I had a bit of a problem, but managed to bring it home and when I turned it on it went “brrrarggghh”.

“The sound immediately captured me because it was exactly the same stuff that Stockhausen used to create pieces like Kontakte and Studie II.”

From there, collecting test equipment appears to have become an addiction…

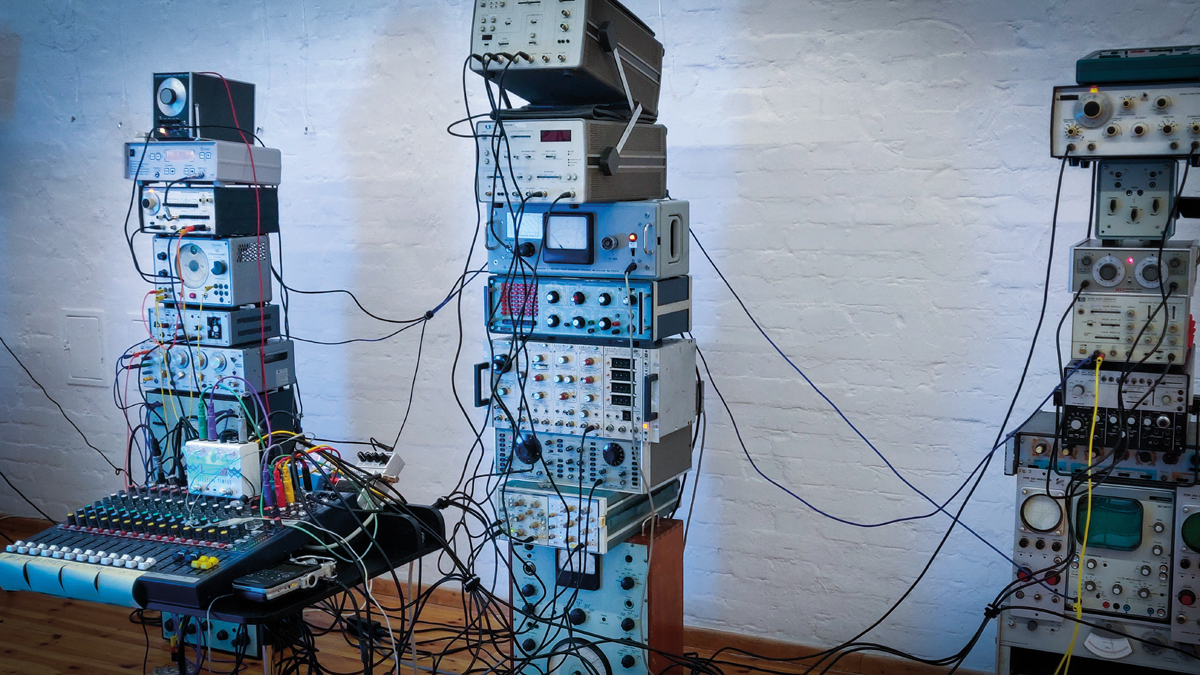

“I decided to buy everything I could find. It was cheap and half of it broken but I amassed so much I couldn’t physically fit any more in the studio until a gallery asked me if I wanted to do a residency for three months.

“Now I had a storage space, so I got a van and took all the stuff there. It looked like a lot of equipment, but in a big wide room it suddenly looked small so I started stacking them.

“Within half an hour there was this statue, and because of all the knobs, lots of faces started to appear, which reminded me of a totem. All this stuff would’ve been thrown away, so I described them as landfill totems.”

What was the majority of the test equipment originally used for?

“It was meant to test telecommunications across the Atlantic and stuff from space agencies like NASA to help shoot rockets into space and make particle accelerators. Arranging them into three statues and patching them together to make a music performance was my way of paying homage to these beautiful pieces of engineering.

“I wanted to use them in a way that was never intended - to make music - and this research equipment has a quality that no synthesizer can ever dream of.”

What was Spitfire Audio‘s involvement?

“Spitfire asked me to collaborate on something at a small synthesizer store in Berlin. I started recording the album out of all these vintage test equipment parts but every time I finished a track I would also go and record each of them separately to see what else I could get. Every day I would take all of those sounds back to the studio and dump them in a big folder, and then I gave it all to Spitfire to create a sample library of the recordings.”

Are you sampling sounds from test equipment or able to interface them with other gear?

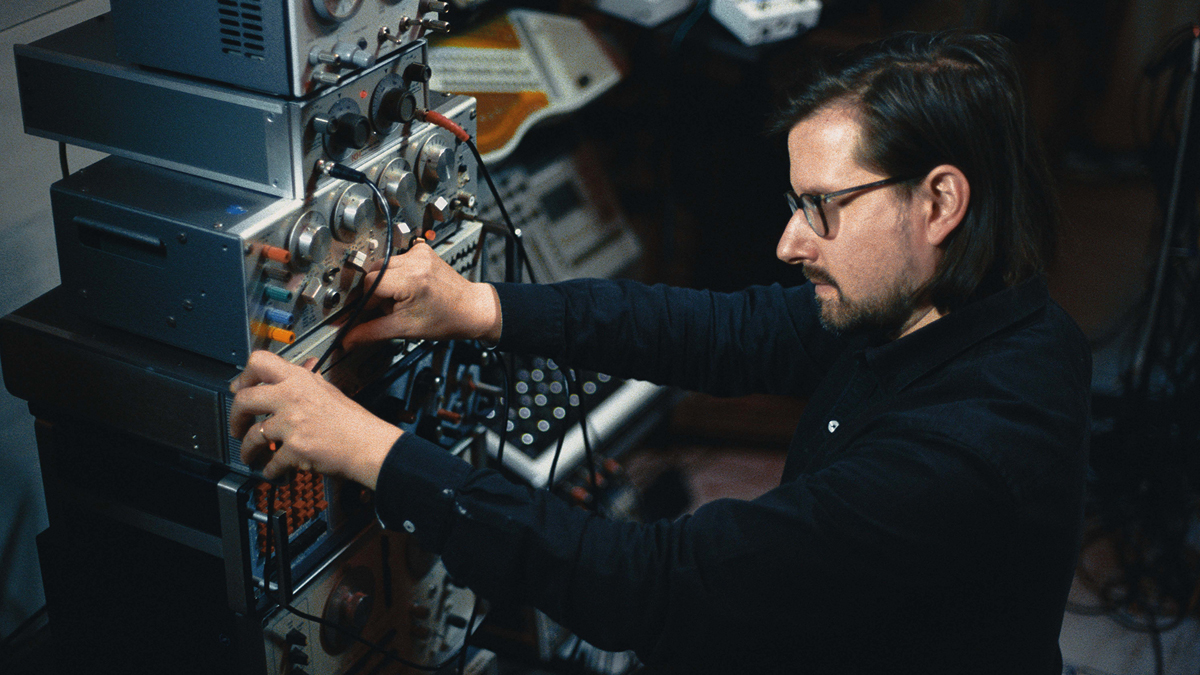

“I can do everything. I played the totems live and the individual test equipment too when recording the tracks. Basically, I connect them to a mixer and watch the levels using an iBook or iPad if necessary.

“Some things you have to watch because some of the equipment was, for example, meant to drive and measure motors and exciters that cause aeroplane wings to vibrate or to electro-shock a human, and that can go up to 150 volts!

“The process of making music from these things is a difficult mode of synthesis but fun, and I feel I make better music when I have to struggle with an instrument. For me, a problem you can solve in your head is better than a head that’s overthinking.”

Do you combine the sound of the test equipment with other, more musical, devices?

“I combine regular synthesizers with the measurement and test equipment in a way where the test equipment controls the synthesizers and the synthesizers shape the sound of the test equipment.

“I find it so exciting to have a Roland TR-707 playing a beat with the toms played by test equipment filters being pinged by a Korg SQ-1 step sequencer. It just gives everything a heavy, super-industrial funk.”

Did you find yourself building an emotional connection to this equipment that you’d effectively brought back to life and repurposed?

“I was always sad when I had to tear the landfill statues down and put them in storage because then it became just a bunch of dead gear again. I think the term is pareidolia, when you see faces everywhere, so you can get emotionally attached to these things quite easily.

“The real beauty is that they contain sounds that no one has ever heard before, including the people that made them. For example, telecommunications testers used devices to send code from one end line to another and when you put that into a speaker you can suddenly hear all these little drones, blips and chords.

“For the library, I recorded stuff at 69kHz, but the Spitfire guys started pitching everything down and because these things are frequency unlimited and going into the megahertz range, they found all this stuff happening in the upper frequencies that would create new sounds.

“That’s why buying this test equipment became so addictive, because I never knew what I would discover, and I have to say that because the components that were used make for such powerful tones, the combination of this insane quality of sound is hard to find the equivalent of in regular synthesizers.

“The closest thing is maybe the Serge synthesizer, which has a similar electric feel, but is still not as extreme or powerful.”

We understand that, on Funktionsverlust, the machine you used died on you during the recording process?

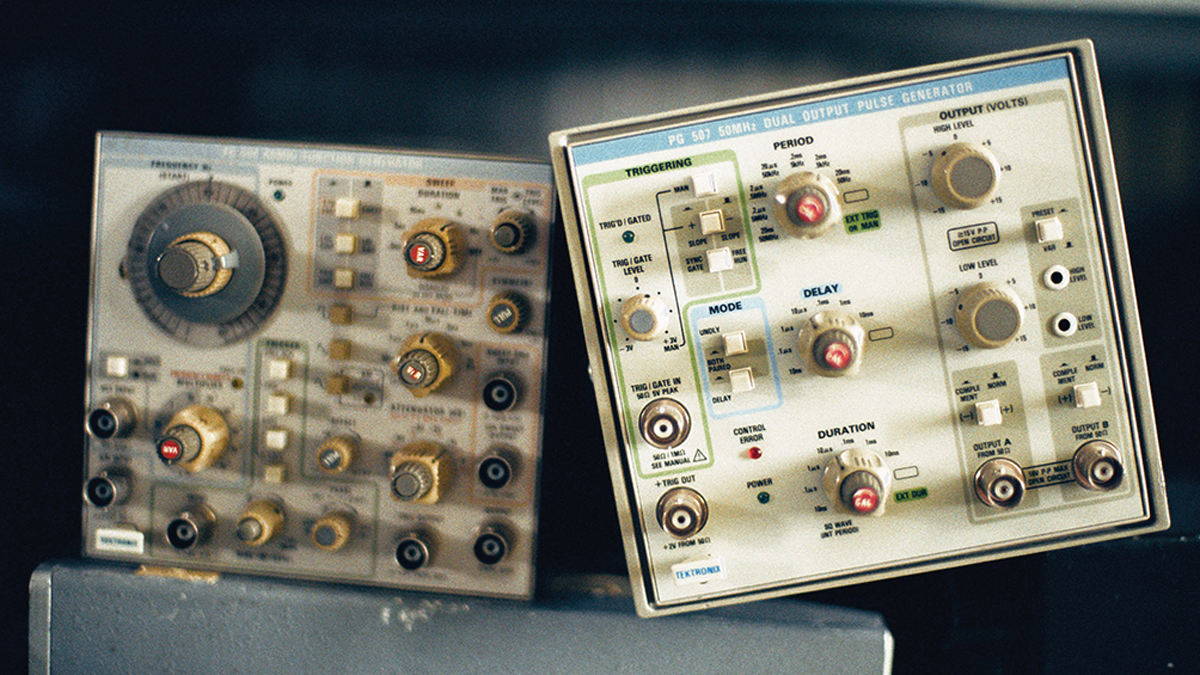

“It wasn’t the only one that died. I was patching up a beautiful modular system by Tektronix who make modular for test equipment. You get filters, mixers, oscilloscopes and function generators, one of which is like a Buchla 258 Complex Oscillator and very beautiful.

“When I started it up the sound began to dance and I wondered why it did that because their job is to put out a stable tone that usually just goes “beeeep”. I built the whole track around that sound, recorded it and went for a coffee, but when I came back I thought ‘what’s that burning smell in here?’ It had died, and I’ve heard they’re almost impossible to fix - but at least it gave me a swansong.”

Knowing the back story to the album’s creation certainly gives it a lot more meaning, but how do you communicate that to people?

“I’ve got a YouTube channel where I talk about these things, but what I’ve found interesting is the art choice from Spitfire Audio, who decided not to show the statues but chose something different from the technical feel of how the album was made, focusing more on the spirit of the music.

“On my previous albums for Misc. Works you’d see gear on the cover, but I was open to them taking a different narrative approach this time, and because the album was recorded in the middle of this health crisis I decided to abandon all hope and make something dark, ambient and hard with a constant sense of threat.

“That threat is also something you get from using these machines; when you patch a cable the voltage might give you a shock and they’d always be shaking and moving a bit when I walked past them.”

You seem to be a big fan of the Teenage Engineering OP-1. Do you see it as a modern equivalent of vintage experimental gear?

“It’s like my Casio SK-1 on steroids, and that’s how I use it, only as a sampler and not using any of the internal engines. I sometimes record tracks into it and it’s always been useful because I do a lot of theatre composing and have to travel a lot.

“Sometimes I use a tape looper to record little micro sounds and play these through the OP-1 because it’s so handy for that.

“Having said that, the gear I cover on my channel is often the really strange stuff and that’s what I’m most interested in. There are always new and exciting Eurorack things coming out.”

What other modules are exciting you right now?

“There’s the Polygogo module by E-RM Erfindungsbüro, which is an oscillator based on the polygonal synthesis method, so you get a screen where you can see the sound being directly represented and it feels and sounds like nothing else. Yes, you can approach some of these sounds with complex modulation, but the way you can interact with the interface and the screen opens up new ideas, and as soon as an idea is combined with an interface that’s playable I’m totally amazed.

The OP-1 is like my Casio SK-1 on steroids, and that’s how I use it.

“Then there’s the stuff that SOMA Laboratory puts out, like the Pulsar-23 drum machine. You wouldn’t have thought someone would release a successful commercial instrument that uses crocodile clips, and yet it’s an amazing drum machine that works beautifully.

“Then you have Erica Synths, who took a look at the old EMS Synthi AKS and decided to do it in their own way, so they put a digital patch matrix in there and now you can do new things with it.

“I also like Make Noise as it’s doing great stuff in modular with its small Strega desktop synth. This is where you feel people are really trying to push things and that excites me.”

It seems like it’s been a long time since synth manufacturers have worked so hard to out-invent each other…

“It doesn’t make sense to compete on cloning analogue things anymore, so everybody wants to create devices that are more innovative. Moog, for example, took a look at subharmonics and polyrhythms to create concepts like the Subharmonicon, which puts them in a new interface to create an innovative and exciting instrument informed by the past, made for today.”

With your background, are you interested in designing innovative products, too?

“It’s something I’m trying to do with my plugin instruments. When I mentioned earlier the 25kg oscillator, I worked with SonicLab to turn that into a VST instrument for the iPad called Fundamental. We created a playable instrument from a bank of sounds that was reminiscent of the past when they had banks of sine oscillators in studios like the BBC Radiophonic Workshop and other electronic music studios in the ’50s and ’60s.

“In those days, you could never play them with MIDI Polyphonic Expression, move the pitch around and make all these complex modulations. Again, you’re looking to the past and adapting it to something modern that you can play on your sofa.”

You turned online hate into art on your YouTube channel, creating what you call ‘destruction loops’…

“Destruction loops started as a typical YouTube challenge. A fellow YouTuber, Simon the Magpie, asked me to destroy tape and listen back to what it sounds like.

“At first I did a composition on three tape machines, ran the tape across knives and sandpaper and waited. After three and a half hours, all the magnetic particles were scraped off the tape loops and you could follow the whole process of destruction in a beautiful way as you could hear the sounds decaying and the resulting change in volume and texture. Suddenly I had something that reminded me very much of how our memories fade, but in a complex way.

“At the same time, my YouTube channel was growing really fast and some people did not really care for what I was doing. I got a lot of negative comments and had a fight or flight response that I felt I needed to deal with.

“I knew that hate comments were common amongst others in my circle so I asked a bunch of YouTube friends to send me theirs. There was some absolutely vile racist, xenophobic and homophobic stuff, so everyone read out their own hate comments and I put the audio onto tape loops. They weren’t synced so they couldn’t play at the same time but they sounded like they were talking to each other and I got all these crazy combinations. Sometimes I felt close to crying, then I was laughing, angry or indifferent, but it was a really cathartic thing to do, and for others too.”

You also run a Patreon page and keep a very close connection with your subscribers. Does that feed back into your work?

“There are so many informed people in my Subreddit showing me stuff to check out and I love sharing and that knowledge is free. I don’t like hidden tricks and feel that the more people know the better everything gets.

“For example, I got a comment about a contraption called Crystal Palace developed by Dave Young for the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. I read up on it and thought it was amazing, so I sent it to Sam Battle from Look Mum No Computer and said, ‘hey, you have to build one’, and because of that I made my own plugin version with AudioThing called Things Motor.

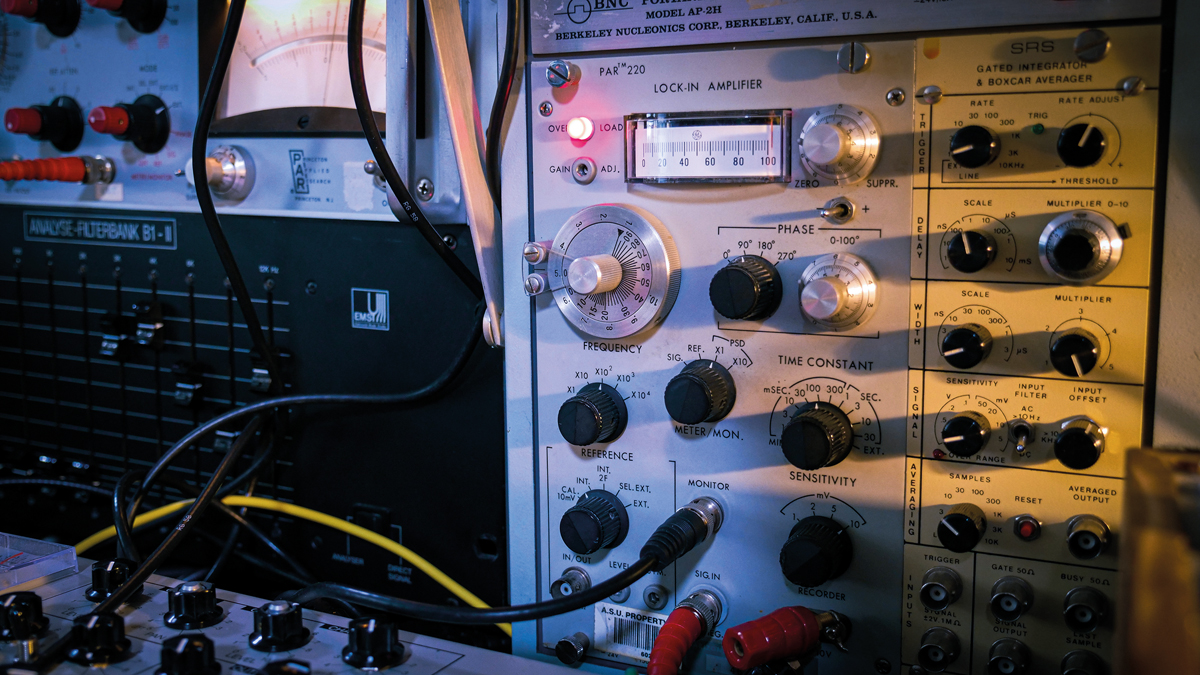

“I also posted a picture of a lock-in amplifier, which is one of my most used synthesis tools. It came from a 184-inch Cyclotron, which was created in 1943 to enrich plutonium for the first atomic bombs, and in the ’70s the unit was also used for medical research into laser eye surgery.

“A journalist on Twitter saw the image and uncovered the whole story, which ended up in the particle research magazine, Symmetry. I was using it to make bass drums [laughs], so any time I can connect dots to history everything feels more rooted and better for me.”

What projects are you working on at present?

“The guys from the Italian Synthesizer Museum gave me something from the Bontempi Experimental lab to make music with and I’m completely infatuated with it, but I’ve got about 10 different ideas right now.

“As the Pet Shop Boys once said when they were asked what inspires them, ‘there’s always a new keyboard’, and for me there is always another rare function generator, filter or strange instrument to play with.”

Hainbach’s latest album Landfill Totems is out now on SA Recordings.