Robert Trujillo talks Jaco Pastorius, film-making and fingers

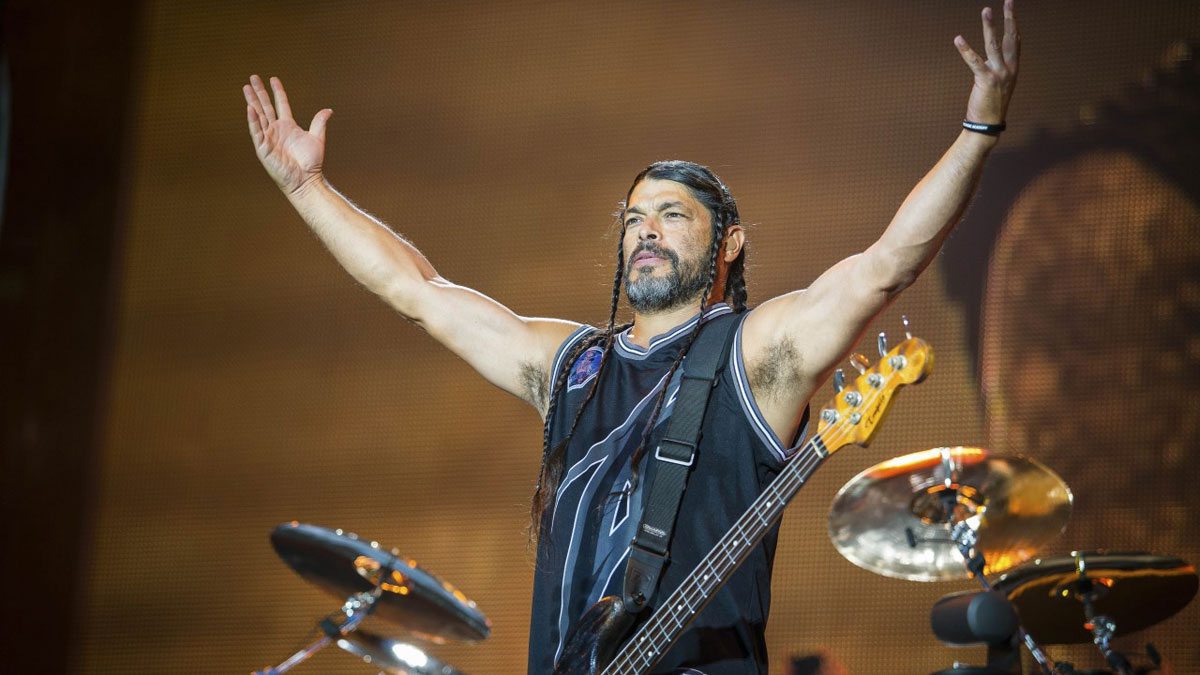

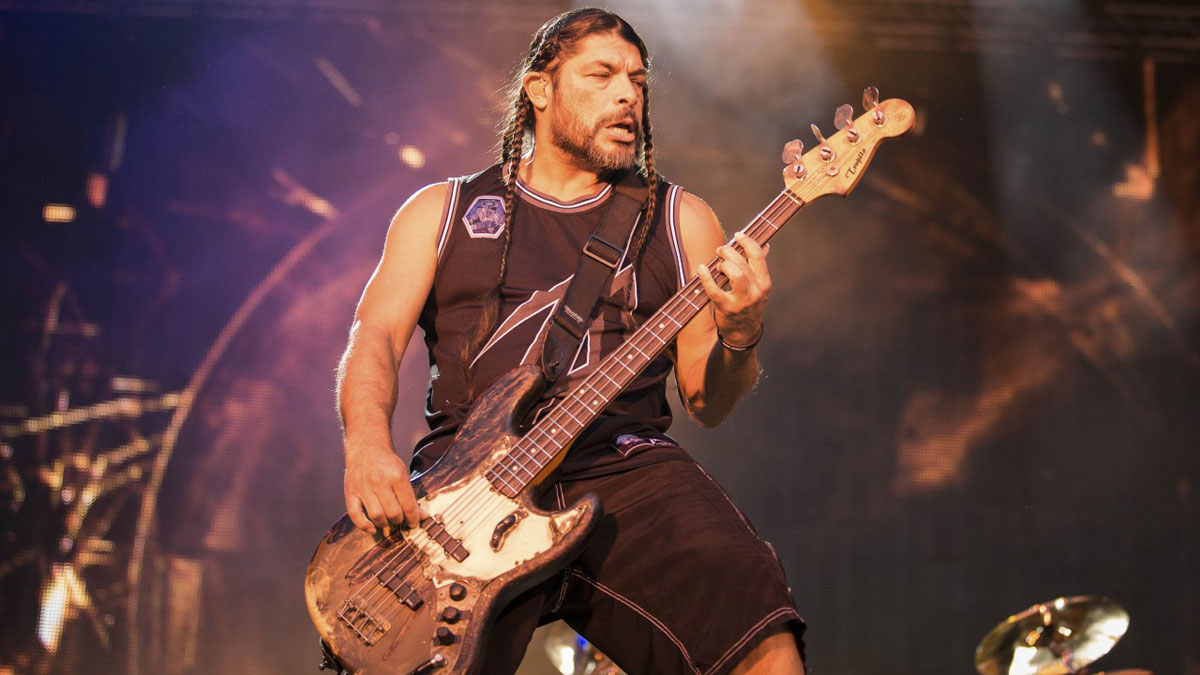

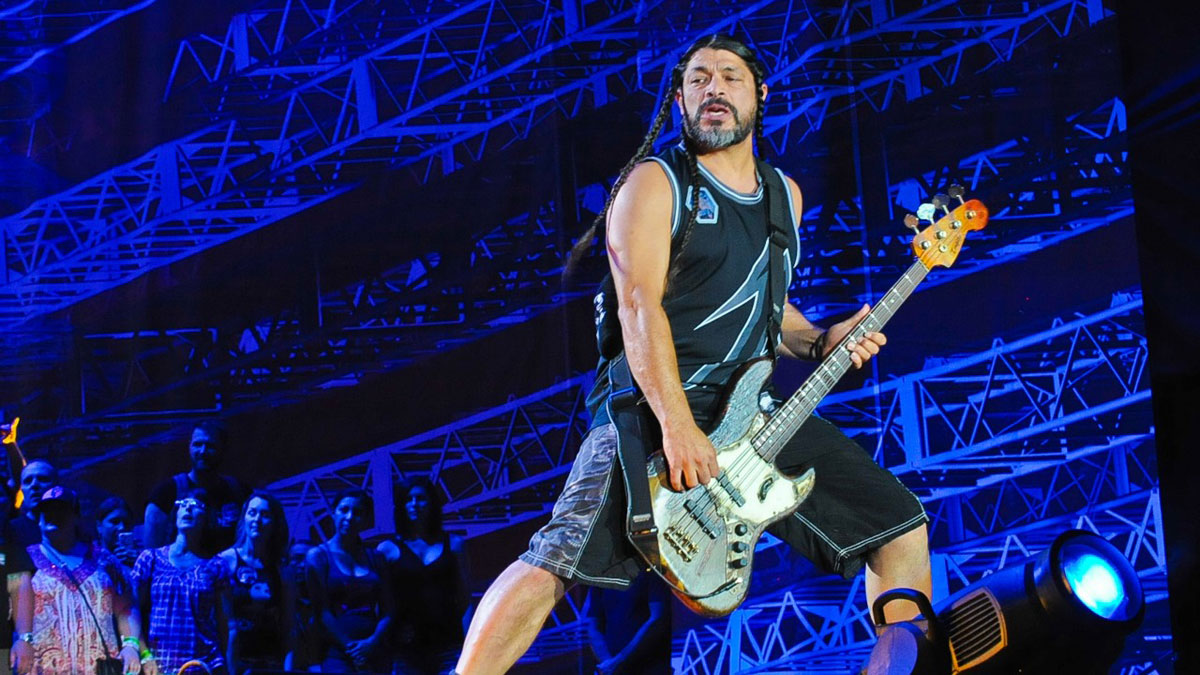

The Metallica man on his passions and projects

Introduction

You know him as the bassist in Metallica, but meet the other side of Robert Trujillo, as we talk technique, and his passion project Jaco Pastorius documentary.

"Battery? You can play that fast with your fingers?” questioned Lars Ulrich at the start of Robert Trujillo’s 2003 Metallica audition. The answer? A resounding ‘Yeah!’

My dad was a flamenco guitar player as a hobby, and I remember when I was young watching him play

You see, the crab-walking, fingerstyle bass powerhouse’s style is underpinned by a love for not just the instrument and its tradition, but a love of great music - whatever its form. It’s a trait that has seen him pick, slap and pop his way through Suicidal Tendencies, Infectious Grooves, Ozzy Osbourne, Black Label Society and, since 2003, Metallica.

Trujillo’s love of music is inspired by his bass hero, Jaco Pastorius - and Robert has spent the last five years making a documentary film about his fascinating life.

The final product, Jaco, has been screened to critical acclaim at festivals around the world, and is nearing a wider release - so what better time to catch up with Robert, and talk blistering bass technique, and why everyone should have a little punk jazz in their outlook.

You play with your fingers, which is less common in metal. What made you decide to take this approach?

“My dad was a flamenco guitar player as a hobby, and I remember when I was young watching him play and hearing that instrument and that style. Now, obviously flamenco is centered around finger technique, and I didn’t even really know that a pick existed back then, because I just saw him play with his fingers.

“A few years after I started noticing players actually using a pick, but I still played with my fingers. I’m not against playing with a pick at all, I had a band called Infectious Grooves many years ago, and that had a fair amount of pick playing; a lot of fingers, a lot of slapping, but also pick.

“I think it kind of blew people away a little bit because they didn’t know that there was pick playing involved, because it was centered around funk.”

Don't Miss

Fast fingers

Do you find your first two fingers are more dominant, and do you alternate between them evenly?

“I think it’s pretty even, but often with Metallica I’ll rotate between those two fingers to maintain speed and consistency. Sometimes, when it gets really tricky and crazy, I’ll throw in my ring finger, and do the same sort of technique.

I tend to play hard, maybe harder than most players, so I have fairly strong fingers

“If it’s sort of a long part of a song where it’s [constant 16th-notes] and I have to maintain it for three minutes, I’ll do that. Then there’s galloping! The galloping technique is very prevalent in thrash metal, and if you’re playing at a higher tempo and you’re galloping, I’d suggest trying to use three fingers.

“In Metallica, we push it a little faster live, and that can be a challenge. I developed a lot of multifinger techniques when I joined, and it’s taken time! It depends on the situation, though. When I joined Suicidal Tendencies, I wore my bass very high, like Mark King, because he was a big influence of mine, and I had to adjust my strap because my right arm was getting cramped up. The blood flow wasn’t there!”

Has playing with your fingers meant that you’ve needed to work on techniques to achieve the consistency you would naturally get with a pick?

“Yeah. Believe it or not, a lot of it is in my fingers. I tend to play hard, maybe harder than most players, so I have fairly strong fingers. Then often, I’ll use a little bit of my nail. That gives it a combination of sound where you’ve got the pad of the finger, then a little bit of the presence from the nail.

“That works for certain songs, but if I’m playing a ballad, I don’t feel like that sound would work. I’d rather go for the pad of my finger, with a rounder tone. It’s all there in your fingertips, you know?”

Making music

How did you get into playing bass?

“My father had a friend who had a Harmony hollowbody bass guitar, it didn’t work plugged in, but I could still hear it. The action was really high, but I played that thing for about a year just doing scales, and I came to realise that bass was the instrument for me.

We didn’t have a lot of money, so we’d take our carpentry skills and revamp instruments

“I saw a bass solo on TV one time, and I realised that whether it was Led Zeppelin, or James Brown or Motown, I was always gravitating towards the rhythm section. I like the funk, you know? I like funky bass. So I started playing, and then my second bass didn’t work through an amp either!

“I got it for $20, and my father was a carpenter. We’d take instruments, strip the paint off, refinish them and make them really beautiful, then use it as a trade-in. Even though it didn’t work - because we didn’t know electronics - we would then trade that instrument for something that did work.

“We did the same thing with amps that were beat up. That’s how we did things, because we didn’t have a lot of money, so we’d take our carpentry skills and revamp instruments. I discovered Jaco around then.”

Jaco was a massive part of your bass education - what drew you to his music?

“Fusion was really exciting to me, Stanley Clarke was bringing the bass to the front. He was soloing, ripping, rocking. Then there was this guy Jaco, and I was like ‘Who’s this guy?!’ He was cool, you know? I saw Weather Report for the first time in 1979, it was at Santa Monica Civic Auditorium.

Jaco could adapt to any situation; like Joni Mitchell. He didn’t know much about her music, but he connected with her

“Seeing him in person was incredible because the bass now had a unique voice and sound. And he looked cool too, he was just this long-haired guy up there, and he looked like my surfer or skateboarder friends. So not only was he shredding on the instrument, bringing it to the forefront with captivating energy, but he reminded us of ourselves.

“He was able to reach a lot of different types of people, and different styles of music. Back then, it wasn’t always so much that you’d have to categorise a musician. People were going to see Ozzy or Sabbath, but also Al Di Meola or Return To Forever.

“Jaco could adapt to any situation; like Joni Mitchell. He didn’t know much about her music, but he connected with her, and they made great music. It was all centered around being creative, and not the ‘rules’ of who you’re supposed to play with.”

Punk Jazz

How did Jaco influence your approach?

“If you listen to a Jaco solo album, you can’t put your finger on any particular style. They have a lot of different personalities. You hear Come On Come Over, which is one of my favourite rhythm and blues funk songs, and he could have done a whole album like that. But then you’re getting Portrait Of Tracy, and Kuru/Speak Like A Child, such an amazing dynamic range of composition.

Jaco would have been the first person to tell any of these people, ‘Hey, it’s all music!’ and that’s kind of the message

“Then with Infectious Grooves, we would try to incorporate Slayer riffs with James Brown and Parliament. As far as the bass is concerned, there are so many moments where I’m just trying to reach into the Jaco treasure chest!

“At the time, I wasn’t trying to learn his compositions, I was trying to pull from the style and the technique as best I could. A lot of times it was reckless, but it was fun. Now I find myself actually learning his songs, I guess because of the film and getting into it for five years.

“Jaco has a lot of different types of fans. He’s got a hardcore jazz/muso contingent who want him remembered as one type of player, but then you have a lot of rock, funk and gospel musicians who think he’s sort of everything. Maybe some of those guys can’t play Punk Jazz, but they still love him. So you get a really wide, broad fan base for him.

“It gets a little dangerous because everybody wants to own him, but Jaco would have been the first person to tell any of these people, ‘Hey, it’s all music!’ and that’s kind of the message of the film.”

Meeting the master

Did you ever get to meet Jaco?

“I saw him four times, and I encountered him at the Los Angeles Guitar Show at the Merlin Hotel. It was really surreal, because it was in 1985 and he wasn’t doing so great back then. Each gear company had a hotel room, and I remember Jaco cranked the amp really loud so it was shaking the walls of that floor. I was the first one to walk into the room and there he was. He was sitting down, playing. I basically just took a knee and sat in front of him.

I own the Bass Of Doom but Felix Pastorius, Jaco’s son, has it. Basically, I sponsored the money to get the bass out of a legal dispute

“Then the room filled up with people, everybody was super excited. He didn’t say anything to anybody, he just kind of looked them in the eye. It was almost like he was letting you know that he was still the man, ‘I’ll take all of you guys on!’ you know what I mean?

“Then his girlfriend came in the room and said ‘C’mon, let’s go!’ and they took off. I just remember being in this surreal state of mind, like ‘Wow, Jaco was just in front of me and there was nobody here!’

“Years later I think ‘Why didn’t I invite him for a burger?’ or whatever. It was the perfect opportunity. Fortunately I got to be in his presence, but I didn’t get to have the conversation that I would have loved to at the time.”

You own Jaco’s Bass Of Doom, too…

“I own it but Felix Pastorius, Jaco’s son, has it. Basically, I sponsored the money to get the bass out of a legal dispute. It had been missing for over 20 years, and it was with some collector in New York and it turned into a legal battle.

“No one was winning, and it was going to put Jaco Pastorius Inc into debt, so I sponsored the money to get the bass from that person. I’m the legal owner, but I don’t have it with me. It’s in good hands though.

“It’s a beautiful instrument, but there’s a big misconception. There are a lot of people who think that I found out where it was and spent all this money and bogarted the instrument, which is so far from the truth.

“I did it to help the family out, it’s the opposite of what people think. I’m not a collector, I’ve got a wife and two kids and responsibilities on a different level.”

Pastorius passion

How did the Jaco film come about?

“I’ve been friends with Johnny Pastorius for 19 years now. When I first met him I said, ‘Someday you’ve gotta make a film about your father.’ And every couple of years he’d say, ‘We’re doing it!’ - meaning he’d started it with other people.

This is something that in my heart is a story that needs to be told

“Then I was asked to be a part of the situation, and I ended up adopting the project, because there was a reality that hit me that if the movie was really going to come out, and be a film of quality, then I’d need to step up and finance it and get it going. I felt that Jaco’s story needed to be told and shared with the world, and in order for that to happen, it needed someone to actually make it happen.

“It turned into a very passionate journey for me, it’s been over five years and a lot of money and time. I have to really tip my hat to our director, Paul Marchand, because he’s been in the trenches with me and Johnny Pastorius.

“It’s been quite a roller coaster ride, it’s not easy making documentary films. They’re passion pieces that cost a lot of money and time and effort, and it’s not like a blockbuster where you do all that and at the end of the day there’s all this profit. It’s not about that. It’s very involved and has nothing to do with me being this rock ’n’ roll musician.

“This is something that in my heart is a story that needs to be told. It’s great to see it, we are where we are and we’ve done some film festivals and we’d like to get it released by early next year.”

Jaco: A Documentary Film premieres on 22 November 2015.

Don't Miss

Stuart has been working for guitar publications since 2008, beginning his career as Reviews Editor for Total Guitar before becoming Editor for six years. During this time, he and the team brought the magazine into the modern age with digital editions, a Youtube channel and the Apple chart-bothering Total Guitar Podcast. Stuart has also served as a freelance writer for Guitar World, Guitarist and MusicRadar reviewing hundreds of products spanning everything from acoustic guitars to valve amps, modelers and plugins. When not spouting his opinions on the best new gear, Stuart has been reminded on many occasions that the 'never meet your heroes' rule is entirely wrong, clocking-up interviews with the likes of Eddie Van Halen, Foo Fighters, Green Day and many, many more.