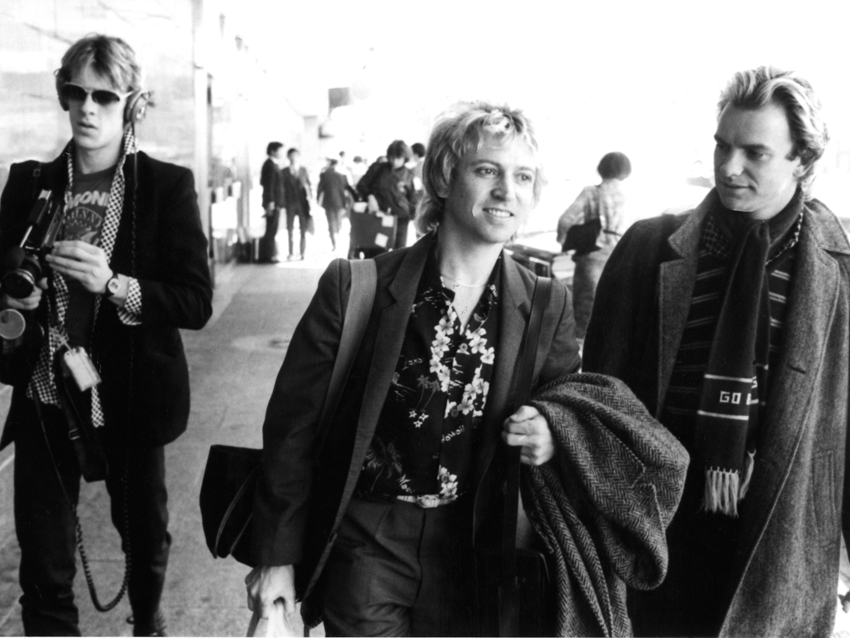

Andy Summers on reliving his Police past in new documentary

"We weren’t just a success; we were a worldwide phenomenon, kind of like The Beatles," says Andy Summers, reflecting on The Police's fame that began with the release of the group's first album, Outlandos d'Amour, in 1978, and had, by the time of their studio swan song, 1983's Synchronicity, overwhelmed the guitarist and his band mates, singer-bassist Sting and drummer Stewart Copeland.

"Finally, it became, ‘Yeah, let’s break up. What a great idea!’ There was a sort of confusion about it, but no resistance. It wasn’t like Stewart and I said, ‘Hey, Sting, we’re not gonna break up. We can’t do it. If you leave, we’re gonna get another singer.’ It was just accepted." Summers explains that, at first, the group kept mum about their break-up pact. "This went on for two years, until I just couldn’t stand it anymore, so I started telling the press, ‘Yeah, we broke up.’ Then the truth was out. It was all quite strange.”

The story of The Police – a trio of musical virtuosos who did what few bands have to guts to do, going out on top after releasing five stellar albums – is so astonishing you'd think a Hollywood screenwriter had dreamed it up. Summers traced the tale in his exceptional 2007 memoir, One Train Later, which also recounted his childhood in Dorset, England, as well as his pre-fame years as a journeyman guitarist in bands such as Zoot Money's Big Roll Band and Eric Burdon And The Animals. One Train Later is the basis for Summers' gripping and highly entertaining new documentary, Can't Stand Losing You: Surviving The Police, in which the guitarist revisits his musical life, focusing, as you might expect, on the personal struggles and creative conflicts that attended The Police's incredible six-year ride.

Ahead of DVD and VOD releases, Can't Stand Losing You: Surviving The Police is receiving a US theatrical release. Summers recently sat down with MusicRadar to discuss the film and to walk down musical memory lane, and he even hinted at how his next album might sound.

What did you discover about yourself or the band in making this film?

“It was a very different process from writing the book. You have to try to get a lot of information into a film that flows, and the reality is that you just can’t get it all in. I tell people, 'If you want the real story, read the book – there’s a lot more in it.' You can’t photograph every page in the book – it’s as simple as that.

“You need a very skilled editor to take the material and turn it into a film that’s got pace and is entertaining. And one of the big things for me was caring about the prose, which I slaved over. In doing the narration, you can’t just say it like it was in the book. You have to take a more conversational approach to make it work. There was a bit of a learning curve to get this just right.”

All three of your have written books, but only two of you have made documentaries. Is Sting going to have the last cinematic word?

[Laughs] “I don’t know, really. He did have a documentary made about him many years ago – Bring On The Night. I don’t know if he’d go out and make one now by himself. He might have accomplished his film slot.”

In the film, you feature a clip from Rock Goes To College in which The Police played Message In A Bottle live for the first time. The song has a tricky riff – did you ever screw it up?

“No. [Laughs] Not really, to be honest. I’ve got that one.”

You must have seen many people mess it up, though.

“Some people, depending on their level of guitar playing, can find it to be a bit of a stretch. I’ve never had a problem with it. I’ve always been able to play it – it’s not difficult for me. I’m not saying that with any sort of ego. It’s just like, ‘There it is.’ I guess it’s because I’m the guy who played it in the first place.” [Laughs]

On being the band's sole guitarist

You came up with one of the most identifiable guitar sounds of all time. Do you remember an ‘Aha! moment’ when you combined echo and chorus in just the right way?

“That’s an interesting point. I’m just wondering if I actually had a moment like that... I was definitely in search of a way to try to sound different from other people. The fact that we had to go out and play for an hour and a half a night made me want to try something new with the guitar sound. I didn’t want there to be one just one sound the whole time. I wanted to add more colors to what we were doing, and I certainly had the ear for it.

“It might have been on something like Walking On The Moon, where I do the big chord at the beginning. It’s got that ringing kind of chorus-Echoplexed chord – and it’s an interesting chord, as well. It seemed to typify the sound of The Police.”

What’s fascinating is how you told Sting and Stewart right at the beginning that you had to be the only guitarist in the band, yet you did have to seek out a way to fill out the sound more. Was innovating a new sound in your head even then?

“Well, yes, that’s very important. I was very certain that I didn’t want to play with another guitar player. It’s just too much playing in the same place. But to be in a trio and to really have the guitar be a big, dynamic thing that can’t be missed, you have to figure some things out. You don’t want people going, ‘Hey, it sounds like something’s missing.’

“It’s great to play with other guitar players – I’ve done it all my life. Actually, outside of a band situation, I really enjoy it. In the context of the band – bass and drums – I felt quite confident that I could cover all the guitar playing ground alone. However, I did think that the uniqueness that I could bring to the voicings would be lost with another guitarist. I didn’t want to fit in with another guitarist; I wanted to take the position, which is what I did.” [Laughs]

Although your sound has been emulated quite a bit, do you feel as though you don’t get the recognition you deserve as an innovator?

“It’s possible. I guess one could always hope for more. [Laughs] You know, why not? It’s a hard question to answer because I feel as if I’ve had a lot of recognition. In some ways, some of the records I’ve made post-Police far outstrip many guitar players in the world and have been far more original, but they didn’t get the notice that the Police records have gotten. No, I don’t feel like it’s been enough, to be honest.”

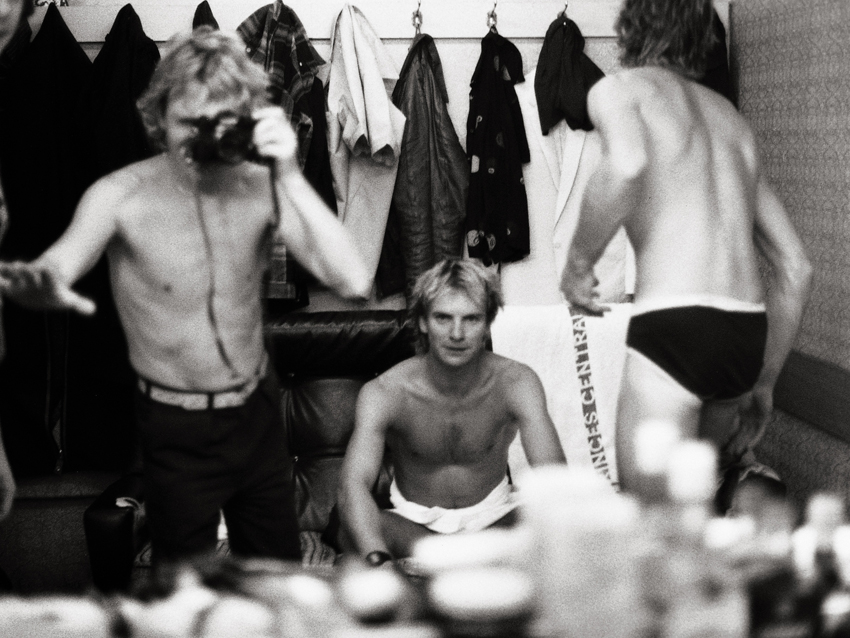

Overqualified punks

You say in the film that you weren’t that crazy about punk, but punk did put you over at the start.

“It’s what Stewart used to call a ‘flag of convenience.’"

But it worked. Certainly you weren’t prog rock or the faceless corporate rock that we had at the time. Punk was a good vehicle to get The Police going.

“It was. Sure, it definitely was. The good thing about punk is that it worked as a catalyst and blew all the cobwebs out of the window, almost overnight. It came in with this raw, fresh, very aggressive and attitudinal position. This was certainly the case in London, which is relatively small and tight – everyone knows everyone. If you weren’t punk at the time, you weren’t gonna get the gig – simple as that. That’s how The Police started, but we weren’t true punks because we could really play. [Laughs] We were a bit overqualified for the punk job.”

You mention that as early as the third record you were thinking that Sting might go solo. There were already signs that the band wasn’t going to be around that much longer?

“Yeah, I might have thought that. There were only three of us, so taking into account the emotions we were going through, I had to consider that was a possibility. But also as an objective person observing the way things go in the music scene, it would have been a standard move – and it was. Eventually, in our case, we rode the whole cliché out.”

It was a pretty important moment when the legendary DJ John Peel gave the band his seal of approval. We don’t really have anybody with that kind of clout anymore.

“No, we don’t. He was the number one DJ in the UK and had a huge following. He had sort of the voice of God in the music scene at that particular time. To get John Peel’s approval was a real sign of authentication. It was at the Pinkpop Festival in Holland when he said, ‘These guys are great.’ It was like, ‘Oh, my God! John Peel’s finally endorsed us. That’s it – now we’re really on the way.’

“We were on the way anyway, but it was very meaningful to us because this was someone that we really admired. John Peel was a very cool guy with very good taste in music at that time. So it meant a lot, and it did help us.”

Band chemistry

Although you cover a lot of music in the film, the focus is more about the conflicts and personal struggles within the band. Intentional?

“You know, in telling a story, I don’t know if you have to be brutally honest, but you have to be pretty honest about what really goes down. It’s just much more compelling as a story if you tell the truth. I had no interest in glossing over the difficult parts and the tensions involved with being a band – it’s important to put it all in.

“I think there’s also a message to people who love this sort of thing or are interested in it that it’s a real journey, and you have to hold on to certain values to get through it all. It’s not an easy ride. You have to contend with other people, other ideas, egos, opinions. You’re gonna have to throw a lot of what you personally cherish out the window – that was very true of The Police. You go, ‘I’ve got an idea,’ and everybody starts laughing. That was true for all three of us: ‘Ha-ha! Here’s how far you’re gonna get past us.’ It didn’t matter who said what. If you could survive that kind of thing, you can survive anything.”

Do you ever hear from any of your pre-Police band mates, like Zoot Money?

“Yeah, I sort of stay in touch with Zoot. He and I went to London together and started up in the beginning. We’ve always remained friends. I hear from him once or twice a year, but I haven’t seen him in a while. If I’m in London, I always think about calling him and going to see him. He’s still going.”

How about anyone from the Animals?

“No. They’ve all disappeared. I ran into Eric a few years ago, but no, none of them anymore. I don’t know what happened to them.”

At one point in the film you use the word “dictatorship” regarding Sting. Most people would bristle at being called a dictator.

“I don’t know if he’s any more a dictator than Stewart or I am. I think we’re all dictators. That’s one of the things that helped to make the band so sparky – you know, the personal chemistry. If I said that to Sting now – ‘you’re a fucking dictator’ – he’d just laugh. We’d both be on the floor howling with laughter.

“It’s a bit like Mick and Keith – we’ve been through all of these things over and over. It’s a sort of marriage in that you know it all and yet there’s enough elasticity that it’s not going to break the relationship. It’s a band, you know? It’s the nature of being in it. You have to be tough enough to roll with the punches, but you come back and state your position.”

Going out on top

Most bands don't go out on top like The Police did. They keep going, and ultimately the records start to suffer.

“Well, that was our intention – to not put out a bum record. We never thought, 'Oh, they're gonna buy it anyway.' I don’t think we ever relaxed and thought that way. We never had that attitude. Every time we went into the studio, we tried to beat the last record. No question about it.

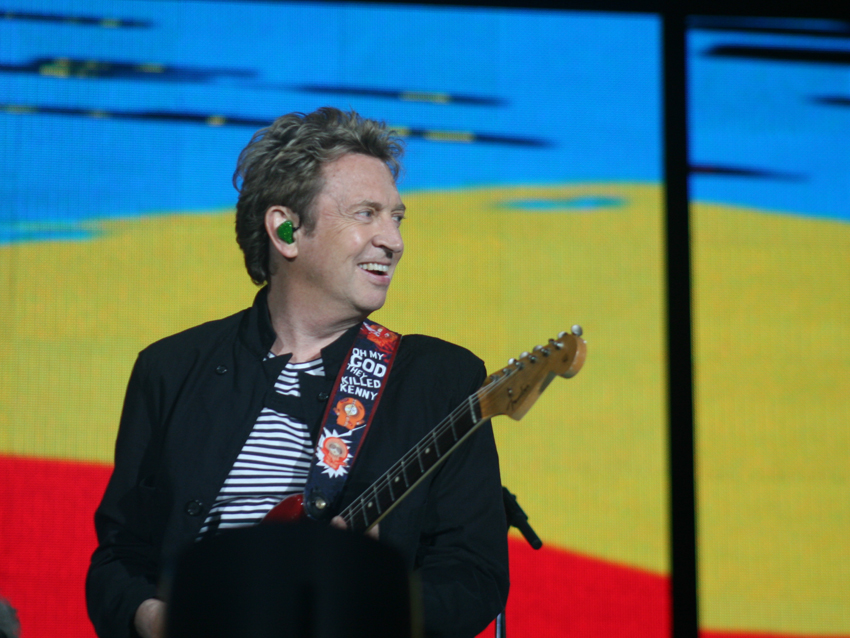

“It’s possible, if we went on for 30 years like some bands I won’t mention, there would’ve been some duff albums – I don’t know if we would’ve ever relaxed into that. It’s never been a part of who I am. I’ve made many records since the original breakup of The Police – I’m making one now – and I’ve honestly always tried my very best to make a better record than I’ve ever made before. I’ve always tried to push it to the edge.”

What kind of record are you making right now?

“I’m in the studio right now. I don’t know what the right word is, but I’m making something that’s very much my music. It’s sort of experimental, avant-garde, very sophisticated and advanced guitar sounds. The structures are interesting and different. It’s in its own place – it’s not really jazz and it’s not really rock. It’s more exotic than that. Maybe it’s influenced by world music. That seems to be where I’m going with a lot of it, a cross between jazz and Southeast-Asian music.

“If you want to hear a track, just to give it a test, go to my Facebook page and there’s a free cut called Qualia, which is what I’m going to call the album. It’s typical of what I’m doing.”

Before the band's 2007 reunion tour, you guys made only a few appearances together. I was at one of the Amnesty International shows you played. It was fantastic.

“Yeah, we did those shows, and I think people didn’t know what to make of us. It was like, ‘What? They came back. We thought you’d broken up! What are you doing back again?’ [Laughs] It was sort of an odd appearance. Which show did you see?”

Giant Stadium. You blew the roof off the place. Well, there was no roof, but you know what I mean.

[Laughs] “Oh, that’s right, Giants Stadium. Yeah, that was a good one.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.