Gary Lucas’s top 5 tips for guitarists: “Music is the most immediate and magical of all the art forms”

The guitar disruptor on working with Beefheart, Buckley and universal blues

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

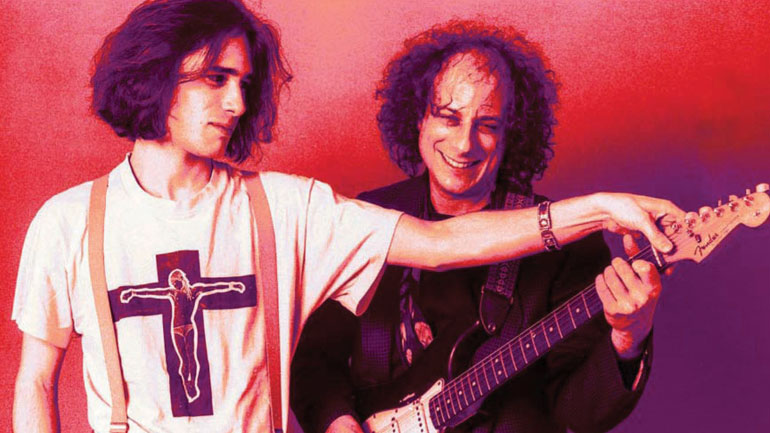

It’s highly likely that even if you’ve not heard of Gary Lucas, you’ve heard Gary Lucas.

The unorthodox New York guitar god has collaborated with half of your record collection – from Captain Beefheart (whom he managed at the tale-end of Van Vliet’s career) to Chris Cornell, Warren Haynes, Lou Reed and Nick Cave.

Most notably, he wrote the innovative instrumentals that would form the basis of Jeff Buckley’s mega hits Grace and Mojo Pin (the experience of which is documented in Lucas’s book Touched By Grace).

He has also composed film scores and worked on near-innumerable projects with musicians from around the world, from Hungarian folk to Chinese pop. Throughout all of his musical explorations, he has had two near-constant companions: his all-original 1966 Fender Stratocaster in Surf Green and a 1942 Gibson J-45 acoustic, the latter of which he got for the “unbelievably low price” of $1,000 in 1989.

Central to Lucas’ masterful understanding of music’s global interconnections – so ably conveyed in his diverse fretwork – is the idea that, through the music we call the blues, we all share a common ancestry: an innate understanding, conveyed by pitches, with which language cannot compete.

We tracked the guitar guru down ahead of his UK tour this week to get a master’s opinion on the secrets of unlocking the guitar, connection and collaboration.

1. Pentatonic scales are not prisons

“Five notes would seem to limit you, but if you hear a blues master – somebody in electric blues like Hubert Sumlin, or Buddy Guy, or Hendrix – what they do with those five notes because they’re adding microtonal slurs, either by sliding or bending those notes, it’s like another dozen notes in the scale, or more – depending on the bends and stretches that they achieve, either with their fingers or a whammy bar.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“You can make what would seem a limited amount of options in that scale suddenly expand into a scale that might have 20 or 30 ‘notes’ in it and they’re all going to be played differently.

“Listen to rock-blues guitar. Jeff Beck was my first hero. He was like, really sly and witty in terms of the way he phrased and how he got from note to note. There was always something audacious about him and the choices of notes that he put in.

A great blues guitarist can make the guitar talk. You’re listening to human speech or a voice wailing and singing. That goes back to this theory of mine that connects most of the music of the world to the blues

“Then I got into Peter Green, who as far as a blues guitarist, I think it was BB King who said, ‘He has the sweetest tone I ever heard; he was the only one who gave me the cold sweats.’ Just in terms of his touch, going back to it being in the fingers, and his sense of dynamics, with a whispering quality and the way it would swell up when approaching his solos. All of these things made what was essentially a limited amount of choices of notes to play into a large variety.”

“A great blues guitarist can make the guitar talk. You’re listening to human speech or a voice wailing and singing. That goes back to this theory of mine that connects most of the music of the world to the blues.

“In pretty much every musical culture that I have studied, from Indian music, to Arab and Jewish music, to Chinese music, to Celtic music, there is a blues feeling, if you really listen. The main thing is using the sliding pitches to express the deepest human emotions of joy and pain – ecstatic joy and suffering.

“When you hear people use vocal techniques of sliding pitches to translate to a guitar, that to me is the essence of the blues – and it’s a universally shared experience. It’s just anything that’s drawn from a reserve of passion in a really sincere way takes a hold of that idea.

“This blues feeling is something that is shared in all of these cultures. You can use it as a fulcrum to bring people together, which is why music is the greatest communicator. It never respects any artificial boundaries. I’m trying to get under my fingers all of this different music and try to just understand why this feeling is similar in a lot of instances between radically different cultures.”

3. Respect your collaborators

“To just respect the collaborator, to let them do their thing is a very important thing to me. I hate to dictate to anybody. Having worked with Beefheart – who was one of the biggest dictators in music, in a nice way, but he was very controlling and it had to be exactly as he heard it – I’ve tried to go the other way and I’ve got fantastic results.

“A guy like Jeff [Buckley], I never told him anything. The only instruction I gave Jeff was on the demo for Mojo Pin where I remember telling him, ‘More Robert Plant!’ But I just trusted he knew what he was doing.

“If you give people a chance, if you have faith and you leave them alone often to their own devices, then they’ll do great. I think it’s when you try to inhibit them and mould stuff too early on in the process that you could get a negative reaction, maybe not to your face, but they’ll resent the fact that you’ve tried to stop the flow of ideas.

“Collaborations are often much greater than the sum of your individual parts. I know that I had some of the music of Grace that I had written before I met Jeff and I tried to come up with some ideas of my own for what might go over the lyric and the melody, and I think that they sucked, you know?

“Having a collaborator is like opening a window and letting in fresh air… By trusting him, and not telling him, ‘You’ve got to do it like this or that’, I got the results – we both did – that we wanted. It was so effortless to work with him.”

4. Wait for the chills

“[When I first demo’d Grace with Jeff] he picked out these lyrics from a book he carried around, his journal, and he had a lot of poetry in there and little drawings and ideas. I had a tape and I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to say ‘start’ and you just start playing.’

“He picks up the mic and he starts, ‘There’s a moon asking to stay…’ and it was won right there. And I have that tape. I was excited because it sounded good, but you know what? I didn’t really zero in on either the lyrics or the melodic line, I was mainly just thinking, ‘I’ve got to make sure that I play my guitar part accurately.’ It was going on next to me and I was taping it but I wasn’t really listening to it that closely, but I knew I was on the path.

Jeff goes out into this dark studio, I’m sitting in the booth and he starts singing in this unearthly voice and it’s like, ‘Oh my God! That’s fucking unbelievable!’

“Then, in the studio recording, Jeff came down and the other guys went home, so I was left with Jeff and the engineer. That was when I got the chills. Because he goes out into this dark studio, I’m sitting in the booth and he starts singing in this unearthly voice and it’s like, ‘Oh my God! That’s fucking unbelievable!’

“It was beyond what I’d ever dreamed. I guess if I’d listened to the tapes, I would have been more prepared for it, but here he was full throttle. It’s like, ‘Where the fuck did that come from?’ I thought, ‘This is going to shake the world, man. This is so fresh.’”

5. Do it to death

“I’m committed to doing this for the long haul. I’ve been doing it to death and I’m going to do it to death. Zappa said, ‘Music is the best.’ I love film, I’m a film buff. I love literature. I used to make films myself when I was a boy. I’m into all of this stuff, but music touched me the deepest. It’s the most immediate and magical of all the art forms, to me.

“Once I started to play shows on my own in ’88 - that was a turning point. I came away from the first one – and I thought it would be a disaster, that no-one would show up – and I got a standing ovation and I made a bunch of money off the door.

“I came home and said to my wife, ‘I just learned I can move a whole crowd of people on solo guitar. I should be doing music… I’m going to hit it as hard as I can now, before it’s too late.’ I was already about 35 at that point. I’d played with Beefheart, but I was so shy and I was so scared that I was like, ‘Well, how am I going to be able to swing that?’

“I’d seen a lot of people go down in the attempt at doing it and get sidetracked or quit out of disgust, so by sticking to my guns and doing it, I built up a certain amount of momentum and I hope it continues. I’ll do the best I can, while I’m around to do it.”

Gary Lucas tours the UK from 4 to 20 May 2018, including dates in Liverpool, London, Glasgow and Bristol.

Matt is a freelance journalist who has spent the last decade interviewing musicians for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.