Debashish Bhattacharya: "Stay close to the music itself, however you can"

The Indian classical slide guitar legend speaks

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

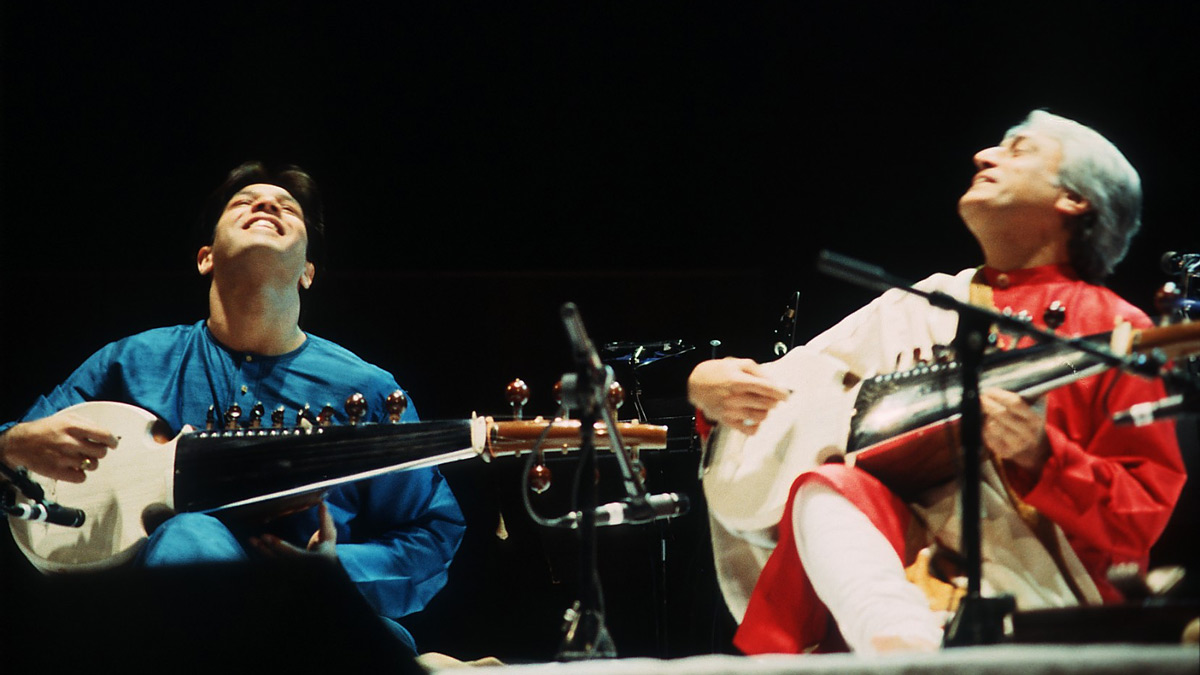

Debashish Bhattacharya is both a radical and a traditionalist. His self-designed slide guitars breathe new colours into ancient Hindustani ragas, and he has taken them around the globe, collaborating with musicians from Hawaii to Okinawa.

He catches up with Darbar Festival’s George Howlett to discuss instrument creation, the hidden harmony in ragas, and how listeners should appreciate the interconnectedness of the natural world.

Like many Hindustani stars, Pandit Bhattacharya was born into a long cultural lineage. He traces his family back through 76 generations of artists, writers, and Sanskrit teachers, and represents the seventh in a straight line of musicians. He established himself early, debuting on All India Radio at the age of four, winning competitions at seven, and inventing his first slide guitar at fifteen.

But his path has never been a straightforward one. He was denied a prestigious classical scholarship on the grounds that he didn’t play a traditional instrument, and just as his career was taking off he left his home in Kolkata to study with the late guitar pioneer Brij Bhushan Kabra.

Imperfection is your walk in the path of perfection. This is a lifelong journey, which will eventually end with you and start with someone else

“In my generation, I’m among only a few musicians who left to study instead of starting to market themselves. I left my family and many local opportunities, travelling 2418 kilometres and entering my guru’s house with a 10-rupee note and no extra garments.

“I didn’t play concerts for those 10 years, and learned under tremendous hardship. My life as his disciple is inexplicable. I would say it was more traditional than anything I’ve experienced in life.”

He also learned North Indian sitar, sarod, and vocal music, but has always been inclined towards outside influences, too.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I learned the Hawaiian guitar as a child, and played 1920s European and Hawaiian compositions aged five to nine. I’ve studied six-string slide and staff notation.”

Growing up, Bhattacharya had to face critics who did not see a place for the guitar in ‘true’ Hindustani music. He had to develop a healthy confidence in his achievements, but acknowledges that the journey of a disciplined perfectionist is not easy.

“Imperfection is your walk in the path of perfection. This is a lifelong journey, which will eventually end with you and start with someone else. Restless nights can be made restful with a glass of something, or can be a source of inspiration to work harder.”

You get the sense that he’s always aimed to expand his own understanding rather than rebel against anything in particular. After all, anyone who designs their own instruments has to rebuild from first principles.

“I created the first Indian classical guitar in 1978 at the age of 15. I designed it from scratch - it wasn’t a modified Western guitar. Since then, I’ve introduced new elements to global slide guitar, including new tunings, fingerpicking techniques, and over 500 compositions.”

Today he wields his self-designed ‘Trinity of Guitars’ - the Chaturangui, a 23-string amalgamation of sitar, sarod, violin, and rudra veena, the Gandharvi, which blends the 12-string guitar with veena, santoor, and sarangi, and the Anandi, a 4-string slide ukulele. He isn’t done yet, telling us three more creations are on the way.

Instrument design is an artistic endeavour, but requires mathematical precision, too. Bhattacharya has always sought to connect different modes of thinking, and it’s no surprise that he found inspiration in school biology classes as well as the goddess Durga.

A raga may be made of notes, but the melody and extended phrases give harmonic shape to it

“Religion and science are useless if they don’t help each other. I find myself happy with or without them, lost in the addiction of pure sound, portraying love in the groove of time.”

This interconnected approach helps him to see shapes others often miss in traditional Indian music.

“We don’t think about harmony the same way, as our music is modal. A raga may be made of notes, but the melody and extended phrases give harmonic shape to it. Chords are already there in the past 60 years: Ustad Amir Khan used tanpuras with three notes (Pa-Ni-Sa), and Ustad Vilayat Khan tuned his sitar’s chikari to a major triad (Sa-Ga-Pa).”

Elsewhere he speaks of Bach’s solo string works in the same regard. They are also streams of single notes, but nobody would see them as absent of harmonic movement. We wonder what his own take on the violin partitas would sound like? Perhaps we’ll find out: Bhattacharya has been writing orchestral scores.

Nowadays he performs and collaborates to acclaim around the world, and says he’s found “most of the innermost answers” to questions around his music. So what drives the multi-pegged maestro to keep on exploring?

“I’m a student, and my drive is to learn new things and refine my actions. That’s the best way to live the rest of my life - I’m just the adventurous raga-guitar wala.”

Pandit Bhattacharya doesn’t sit on the boundaries between his traditions - he fully embodies them. However, he also recognises the importance of keeping disparate styles distinct.

“I can play three different styles - it’s about creating new wings, not polluting. But I don’t mix them when I play traditional dhrupad style.”

Unfamiliar music elicits different reactions from a listener, so does he consciously change his style when playing to Westerners?

When I perform, the dialogues are between my own guitars and my beloved ragas

“I walk to the studio or stage in the same way, whether in India or abroad. When I perform, the dialogues are between my own guitars and my beloved ragas.”

Overall he describes himself as “an optimist and a pessimist” about the future of Indian classical, recognising that young musicians are growing up in a much faster-paced world than their forebearers. He has seen this firsthand - his daughter Anandi is an accomplished singer who releases her own albums as well as featuring on his, debuting this year with Joys Abound.

“I love younger-generation musicians, but they miss some of what we had - gurus and teachers who were not so busy earning everything needed to sustain life. They have it harder, suffering from the viruses of judgements, negativity, self-marketing, and short-term pleasures.

“But if a student has the right mixes of passion and focus then it will bring them benefits and serve the Hindustani tradition. Illiteracy is not a problem, but half-education is.”

Bhattacharya takes his own teaching commitments seriously, working with thousands of students around the globe. He encourages modern learners to stay discerning and integrate their musical approach.

“Taste is the filter. I think art claims surrendered lovers to itself. And leading a scholar’s life is not enough - there are no boundaries like this in nature. We segregate and draw lines for particular purposes, but everything connects, including the sixth element: sound.”

“Expansion inward is more important than outward. Stay close to the music, however you can. My gurus taught me that - I’m still trying to be close enough.”

Darbar Arts & Heritage believes in the power of Indian classical music to stir, thrill, and inspire. To find out more, sign up for the Darbar newsletter or explore its YouTube channel.